Chapter 8 - Department of Natural Resources

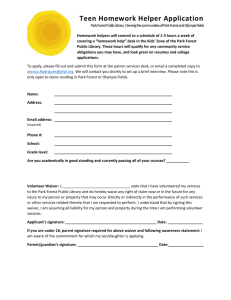

advertisement