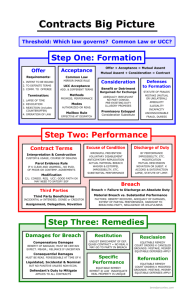

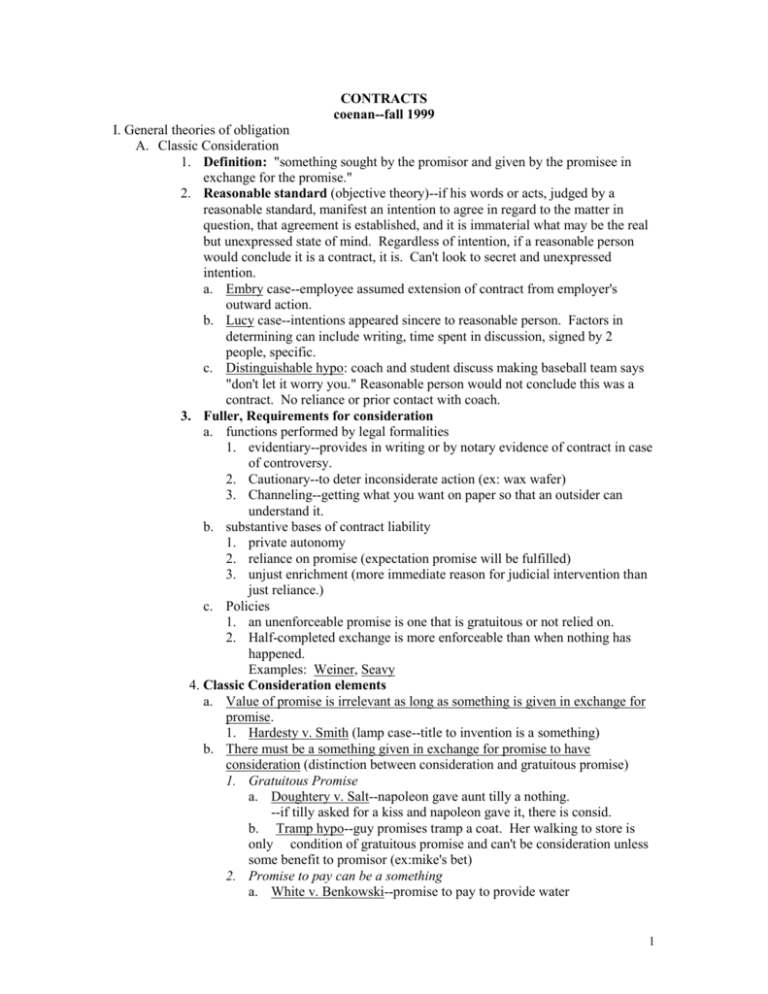

contracts

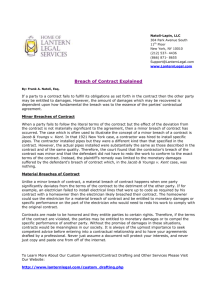

advertisement