Chapter 3 Trinity as Communion: A Liberation Theology Perspective

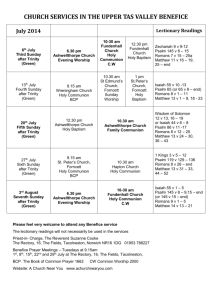

advertisement

Chapter 3 Trinity as Communion: A Liberation Theology Perspective We have already seen above that the understanding mission as missio Dei is not something abstract. On the contrary, it is very relevant for the life of the people, and, above all, it gives a method on how to do mission. Liberation Theology in a special way, offers deep insights which enable us to understand why mission in a context of oppression and conflict should be identified with the struggle of the people. When we are faced with the reality of oppression mission becomes as Jon Sobrino argues, ‘an activity for the purpose of changing reality’ (1990:689). Leonardo Boff is the Liberation Theologians who explored Trinity in the deepest and most systematic way. His ideas help to contextualize mission as God’s activity and help us to answer why the model of mission in Ash Road is mission as missio Dei. 3.1 Politico-Religious Difficulties for the Living experience of a Trinitarian Faith The Trinitarian understanding of God has been taken very seriously by Liberation Theology. Such seriousness was also recognized by the Pope’s visit to Puebla on the occasion of the Latin American Bishops assembled there, when he stated that: “Our God, in his most intimate mystery, is not a solitude, but a family. For he intrinsically contains paternity, filiation, and the essence of the family that is love: this love in the divine family is the Holy Spirit” (Boff, 1990:389). However, the belief in the Triune God for the faithful throughout the world is a real struggle. According to Liberation Theology, it is possible to emphasize a political and a religious reason for such a struggle. In the area of the political we are used to political authoritarianism which is expressed in a heavy concentration of power. The family as well, is fashioned around a old patriarchal figure that does not allow for equality in parental bonds. The ideology created by these political phenomena has taught that, just as there is one God, so there must be one King and one law. In the religious sphere, according to liberation theologians, we assist to a similar phenomenon: the centralization of power in the hands of a single person, the Pontifex Maximus. Similarly, the clericalization of the Church led to an accumulation of power in the sole figure of the priest. The result of this, visible in the hierarchical conception of the 31 Church, has favored a unitarian vision of God. This rigid monotheism is translated in the life of the Church in problems of participation, communion and inclusive relationships and, pastorally is highlighted in the common experience of the faithful who worship a kind of separate God to the exclusion of the other two persons. Thus, there is a religion of God the Father where faithful are mere servants who must conform to the sovereignty design of the Father in heaven, there is a religion of the Son, where Christ is all, a Teacher, Brother, Chief, Leader and, finally, there is a religion of the Spirit very popular among the social elite characterized by enthusiasm, creativity to the detriment of any historical dimension. This disintegration of the Trinitarian experience is essentially due to the neglect of the trinitarian dimension of God: the communion among the divine persons. 3.2 Trinitarian Faith as Root of Social Commitment The question Liberation Theology tries to answer is: “What is the relevance of the Trinity for impoverished people?” In order to answer this question Liberation Theology understands the Trinity as a communion. The believing Christian therefore, understands the Trinity in faith and tries to mediates the insights that his/her faith provokes.Secondly, compare the social reality to such a Trinitarian faith and asks to what extents it contradicts a communion among differences. The commitment to the transformation of society is grounded in the Trinitarian faith, because the Trinity is the prototype of the ideal society, a society where differences are seen as richness and where every human being has life to the full. 3.3 The Father’s Two Hands: Son and Spirit The Trinity as it has been revealed to us has followed three different routes: the route of history, the route of the Word, and the route of the manifestation of the Spirit in the Christian Communities. The Trinity is in fact revealed in the lives of human beings, in religions and in the common history of people. Secondly, the Trinity has been revealed in the life, passion, death and resurrection of Jesus and, finally, it has been revealed in the 32 manifestation of the Spirit to the Christian communities. In all these ways of revelation all the persons of the Trinity were involved; nevertheless, the starting point of every reflection is Jesus, because He revealed who God is. It is in Jesus that Liberation Theologians find the revelation of the Trinitarian mystery. Jesus, first of all, revealed the Father. We read in the New Testament that Jesus referred to God as a Father. He used above all the expression Abba, especially in His personal prayer (Lk 3:21-22; 5:16; 6:12; 11:1-5; Mk 14:32-42). Jesus’ experience of God was not confined to a mere doctrine but was commitment to the Kingdom and practice of liberation in favor of the poor and the outcasts. Jesus’ relationship with the Father reveals a certain distinction and a deep intimacy at the same time. Distinction is revealed in those passages where Jesus prays, asks and prostrates in God’s presence and, intimacy is shown in His name for God: Abba. In Jesus is also revealed the Son not so much because he referred to Himself in this way but because he acted as the Son of God. He made God visible in His mercy and goodness. The revelation in the occasion of Jesus’ baptism is also important. As a matter of fact, in this occasion the divine testimony is explicit. John’s theology expresses the fact that Jesus and God are one thing (10:30; 17:21). Finally, the central point of the Son is during the paschal mystery in which the Trinity is revealed as a community, with the Son delivering himself up out of love and loyalty to the Father and the Father responds to the Son by raising him from the dead. The fullness of Jesus’ new life shows the presence of the Spirit, an expression of the new life of communion among the divine persons. Finally, in Jesus is revealed the Holy Spirit. This revelation is an ongoing process in Jesus’ life. He is the permanent vehicle of the Spirit. It is the Spirit who enables Jesus to perform wonders and deeds of liberation. This power is in Jesus but at the same time is distinct from Jesus: the Spirit and the Son have the same nature of life, communion and love, but are distinct divine persons. 3.4 Human Reason and Trinitarian Mystery Praxis plays a pivotal role in liberation theology. Faith and doctrine come only after life, experience and celebration. This is also what occurred to the first Christians: they begun to express their Trinitarian faith with doxologies, sacraments and professions of faith and 33 only afterward they reflected upon what they had celebrated and lived. The first question to arise was: how can we reconcile the strong monotheism of the Hebrew Scriptures with the faith in the Trinity? It is in answering to this kind of question that the first heresies arose. The Christian community rejected three forms of representation of the Trinitarian mystery: Modalism, Subordinationism and Tritheism. Modalism taught that there can be only one God who appears under three different modes, which are a kind of mask with which the same God is presented as Father, Son and Holy Spirit. Subordinationism affirmed that only the Father is fully God and the Son and the Holy Spirit are subordinate to the Father and they are not God. Tritheism saw the three persons as independent and autonomous of one another therefore, at the end there are three gods. The Christian community tried to answer to these heresies through ecumenical councils. The principal ones are those of Nicea (325), Constantinople (381), Chalcedon (451) and, much later, the Fourth Lateran (1212) and Florence (1431-1447). The theological reflection developed through these councils helped to build up a technical language which could obviate mistaken understanding of the Trinitarian faith. The result obtained by this technical language was a most rigorous theological understanding but a big loss in term of faith experience. 3.4.1 Technical language concerning the Trinity We have now to consider some of the technical words expressed by the Church’s theological reflection. - Nature / Essence / Substance: They denote the unitive factor in God which is identical in each of the divine persons. The nature / essence or substance is one and unique. - Person or Hypostasis: It refers to the distinguish element of God and denotes each of the respective persons. Each person is thus distinct in itself but always in relation and in openness to the others. - Procession: It describes the manner and order in which one person proceeds from another. In the Trinity there is not causality; rather it is a technical word which denotes communion in a certain logical but real order of understanding. The Son and the Holy Spirit are not less eternal, infinite or almighty than the Father. There are two kinds of 34 procession in the Trinity: the generation of the Son and the handing over of the Holy Spirit. The procession of the Son is explained as the perfect knowledge of the Father by himself who generates another image of himself. Whereas, the procession of the Spirit is the concrete result of the contemplation of the Father and the Son of each other. - Relations: This term refers to the connections among the divine persons. The Father, in relation to the Son, has parenthood; the Son, in relation to the Father, has filiation; Father and Son, in relation to the Holy Spirit, have active spiration; the Holy Spirit, in relation to the Father and the Son, has passive spiration. These relations distinguish the persons from one another. - Perichoresis or Circuminsession: These words denote the radical coexistence, cohabitation and interpenetration of the three divine persons with one another. In the Trinity there is not any hierarchy or superiority but only circulation of love. The Trinity is a communion of equals. - Mission: Mission is the presence of the divine person in the concrete history of creation. It is a self-communication of God. There are basically two missions: that of the Son, who became incarnate in order to divinize human beings, and that of the Spirit who dwells in us in order to unify all things and to lead all creation to the Reign of the Trinity. - Immanent Trinity: It is the Trinity considered in itself, in its eternity and perichoretic communion among the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit. - Economic Trinity: the Trinity as self-revealed in human history and as acting so that we might share in the Trinitarian life With these terms in mind it is possible to describe the different approaches which theology has been developing in regard to the Trinity. 3.4.2 Systematizations of Trinitarian Theology The various approaches to the Trinity did not happen in a vacuum but they have been influenced by the different contexts in which they arose. In the Greek world, first of all, the predominant approach was in relation to the person of the Father who is the source and the origin of all divinity. This was essentially due to the Greek emphasis on monotheism and the absolute monarchy of God. On the contrary, the Latin world 35 approached the Trinity with a strong emphasis on the single divine nature. The one God, according to the Latin was an absolutely perfect spirit. Modern theologians, finally, begin with the relations among the divine persons. God, according to this approach is Father, Son and Holy Spirit, in perichoresis among themselves. The persons are three but always in relation among them; they are three persons in one communion. It is this kind of approach, a approach that is inspiration and good news for impoverished people, that inspires Liberation Theology. 3.5 A Liberative Conception of the Trinity The ultimate foundation of Christians’ commitment to liberation can be found in the Trinity understood as mystery of communion among distinct persons. The fact that the Trinity is a communion of persons has huge implications for impoverished people. But what does it mean to say that God is a communion? The Scriptures proclaim this everlasting communion saying that God is one God and S/he is the God of life. Life is a mystery of spontaneity, a process of giving and receiving. Life implies “presence” in the sense of intensification of existence. Life is communication in itself because a living being speaks for him/herself and, every human being, forces others to take position in his/her regard. Therefore, every life is a call to establish relationships with others and in this way we can understand life as communion. Life is not to be kept for him/herself but is for the others. Something similar occurs in the Trinity. Each person is for the others and in the others. Communion is the only human word capable of expressing such a relationship. Hence, life is the essence of God. And life is communion given and received. This kind of communion is Love. Communion and Love are the essence of God the Trinity. God therefore, can be described as a communion. Communion is not merely a thing but a relationship between things. In order to be in communion is necessary to be present to one another. This is not a simple physical presence. In order to make communion or to “commune” one has to face another. Communing implies presenting oneself to another and at the same time offering welcome. Another important characteristic is reciprocity. Communion implies a movement of two individuals. Communion cannot come from one side alone. Reciprocity implies two presences 36 relating to each other. The third important characteristic is immediacy. When communion is real two persons want to encounter each other without any mediation. Hence, communion implies intimacy, transparency, and convergence. Finally, the product of relationships of communion is community. Community spirit implies utopia, a living together that is already a form a new society without class distinction, formalities and oppression. In God we find the presence and the wholeness of these values. God is absolute openness, supreme presence, total intimacy, eternal transcendence and infinite communion. God’s project for humanity seeks to reflect God’s way of being. Trinity seeks to be reflected in history, through people sharing their goods in common, building up egalitarian relationships and sharing what they are and what they have. Life and Communion are expressed theologically with Perichoresis. Perichoresis denotes first of all the action of involvement of each person with the other two. Each of the persons allows the others and itself to penetrate and to be penetrated. This is the natural life of the Trinity and it happens because of their love. Thus, each of the persons is eternally in a relation of love with the others. The effect of this eternal interpenetration is that each person lives and dwells in each of the others. We can thus understand the Trinity as a mystery of inclusion as the Council of Florence (1441) has taught: “The Father is wholly in the Son and wholly in the Holy Spirit. The Son is wholly in the Father and in the Holy Spirit. The Holy Spirit is wholly in the Father and in the Son. None precedes another in eternity, exceed it in greatness, or surpasses it in power”. The point that clearly emerges from this conciliar statement is that the divine perichoresis precludes any relation of power or subordination among the three persons but all are equally eternal and infinite. 3.6. Trinitarian Communion as Critic of and Inspiration for Human Society The inner life of the Trinity produces a critical attitude to personhood, community, society and the Church. On the personal level the dynamics of the Trinitarian life are opposed to the dominant culture which stresses the predominance of the individual. Understanding human beings as created in the image of the Trinity presupposes the consideration of relationships. 37 Human beings are always in relation to others moreover, only through being with others people are enabled to build their own identities. Being in relationship with others does not exclude the fact of being in relationship with creation, society and history. Human beings therefore, are not called to be alienated from the conflicts and process of social transformation. On the other hand, they are called to build human society and humanizing relationships. The Trinitarian dynamism moves also critiques to community. In this sense community should consider itself not as a closed and reconciled world in itself but on the contrary, it has to place itself within a greater whole. “Communitarianism” is a degeneration of Community and not a reproduction of Trinitarian dynamism in history. Both models of society, capitalism and communism, do not take into consideration the real needs of human beings and have degenerated in terrible aberrations. Concerning the social sphere, Trinity is source of inspiration rather than an obstacle. Trinity highlights society as it should be, it is a horizon where Christians can cultivate utopia. A society inspirited by Trinity is a society that cannot tolerate class differentiation, domination and marginalisation. On the contrary, a society rooted in the Trinitarian model it is an inclusive society where equal opportunities are granted to all and everyone finds the possibility of expression hi/herself. A society inspired by the Trinity is a society that takes into consideration democracy, not so much as a definite social structure but as the principle underlying and providing inspiration for social models. It is a basic democracy which guarantees participation and equality among everybody. Because participation is not granted to the majority of people, it has become urgent a process of liberation started by the oppressed themselves, a process which could bring participation and communion among people, above all the oppressed. Trinitarian communion can also be critical concerning the organization of the Church. The Church is a theological and mystical mystery; nevertheless, this mystery takes a historical shape moulded also to particular conceptions of the world. From this point of view, the representation of church unity lends to a vision that comes from pre-Trinitarian or a-Trinitarian monotheism. As a matter of fact, the structure of the Church is based on a single church body, a single head, a single Christ and a single God. This model justify itself affirming that the celestial monarchy is the foundation for earthly monarchy. The 38 sacred power, according to this model, finds its justification in a hierarchy which, de facto, does not exist. In this model the authority adopts a paternalistic approach: it does everything for the faithful but very little with the faithful of the People of God. Trinity helps the Church to understand that there should be an ecclesial koinonia. The Church, according to the Trinitarian dynamic is a community of the faithful in communion with the Father, through the incarnate Son, in the Holy Spirit, and in communion with each other and with their leaders. It should be a Church which welcomes and respects the gift of differences as gift of the Holy Spirit itself. The Trinitarian vision produces a vision of the Church that is more collegiality and communion than hierarchy and power. 3.7 Understanding the Trinity from the Perspective of the Struggle of the Oppressed Understanding the Trinity as a communion of persons is the root of every Christian commitment for social transformation, because Trinity is the prototype of what a society should be. If this is the starting point and the principle towards which every oppressed community should look at we should ask why people, especially impoverished people, struggle around the world. Is there any link with the Trinitarian dynamics? And, ultimately, where the struggle of the oppressed is grounded? Taking in analysis the struggle of Abahlali BaseMjondolo (shack dwellers movement) in Ash Road shack dwellers community, I want to highlights several things which correspond to the Trinitarian dynamics. First of all, shack dwellers become aware of their dignity and their ontological goodness. There is a time, a day, an occasion when they recognize that they are not created in order to suffer the way they suffer, in which they recognize that they do not deserve to live such harsh life. This process of awareness, if seen through theological categories, can be understood as the awareness of their divinization. The Son was sent into the world in order to divinize human beings; moreover, the goal of the Trinity is to draw every human being to itself so that everyone may participate in its inner life. Therefore, the discovery of our own dignity is rooted in the divinization gained by the Son and by the Trinitarian dynamic. 39 Another important point of comparison is that Abahlali Basemjondolo is not struggling for power but to create a new society. In other words, power is not the goal of their struggle; they do not want to overthrow the government rather they challenge the government to recognize that South Africa belongs to every citizen. They are struggling to create a community of equal and to abolish hierarchical relationship. The critic of power is a very strong component in the struggle of the shack dwellers, and their relationships, processes of participation and decisions are molded upon this critic. In the process of struggle they are already building up such new kind of relationships. It is the process of Umzabalazo (Struggle) which enables them to create what they are longing for: equality, participation and dignity. Even the repression of the state and police become a mean through which the not-yet is already built and, in this way, the kingdom becomes historical. This process has been described magisterially by John Holloway: ‘Nel processo di lottare-contro si formano relazioni che non sono l’immagine speculare delle relazioni di potere contro cui si dirige la lotta: relazioni di fratellanza, di solidarieta’, d’amore, relazioni che prefigurano il tipo di societa’ per cui stiamo lottando’ (2004:206). The model of Trinity as communion therefore, can be seen as the ground where the struggle of impoverished people is rooted. Moreover, the communion model can uphold and sustain the utopia of a new form of society. I also believe that the communion model challenges the Church and her praxis. Why the Church should be involved in the struggle of impoverished people? Bosch affirms that the preferential option for the poor helps above all the Church to Church: ‘it was not a case of the poor needing the Church, but of the Church needing the poor – if it wished to stay close to its poor Lord’ (1991:436). Is the Trinity a model which pushes the church to be identified with the Umzabalazo? We have seen that Jesus revealed God. He is the central person, in order to understand the Trinity. Jesus revealed a God full of compassion for poor, marginalized and oppressed. Jesus revealed a God who made a clear option for the outcasts of every time. In my understanding the Trinity is not impartial and universal. On the contrary, through incarnation, the Trinity opted for the poor. Therefore, the Church in order to remain faithful to the God revealed by the Son is called to renew her option for the poor. In this 40 sense the poor are not only the beneficiaries but the moving principle of her actions. According to me, a Church identified with the struggle of the poor and inspired by the Trinitarian communion should do two things. First of all she should strive to make impoverished people aware of the righteousness of their struggle pointing out at the Trinitarian dynamics. Most of the time, poor people are not aware of the link between their praxis and the being of God. The Church has therefore the task to carry out her mission and proclaiming the good news. This good news is a deep one: impoverished people are building what God dreams for human beings and, more radically, they are building a society molded on what God is. Secondly, the Church should create spaces for critical reflection, spaces where poor people can meet and reflect about God’s presence in their concrete situations. Also these spaces should be places of communion among equals, where real participation is lived out. These spaces should be witness of God’s presence among the people, a presence of communion, equality and “new creation”. 41