atj self represented working group - National Legal Aid & Defender

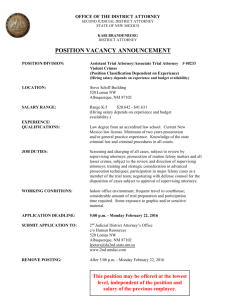

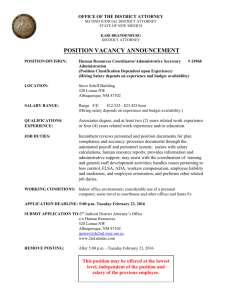

advertisement