The Babbling Burglar and the Summerdale

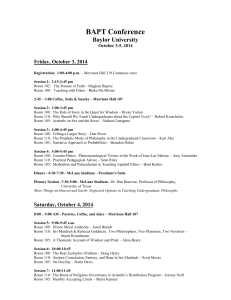

advertisement

The Babbling Burglar and the Summerdale Scandal: The Lessons of Police Malfeasance More than forty years after Chicago's worst police scandal, the department is again under siege. A look back at Summerdale and its aftermath. By: Richard C. Lindberg In the darkened doorway of a liquor store on Berwyn Avenue, Officer Frank Faraci of the Chicago Police Department's 20th District (then the 40th)—Summerdale—stumbled into an old acquaintance. "Well if it isn't the little burglar Richie Morrison," he sneered. The smell of liquor on the breath of the police officer was unmistakable. Morrison nervously asked how things were going at home. The glib little thief whose chosen career as a skilled cat burglar was firmly planted by 1958 when this encounter took place, was very polite and respectful to the boys in blue when it suited his needs but he never was very comfortable in their presence. "Well, they would be a little better if you would cut us guys in on some of your jobs," Faraci propositioned. "You know Al Karras and some of the other fellows, and we'll go along with the show. After all we like nice things too." Morrison's chance encounter with this Summerdale District police officer that fateful evening set in motion a historical chain of events—an incident that would forever alter the landscape for police officers in the City of Chicago—and the future administration of law enforcement across the United States. The devastating scandal involving eight Chicago Police officers who conspired with the burglar Morrison at various times to loot North Side retail stores. The scandal rocked the Chicago Police Department and the confidence of the public to its bare foundations. The ensuing events nearly cost Mayor Richard J. Daley his career as a big city powerbroker, and led to systematic change put in place by a scholarly reformer known as the "professor:" Orlando W. Wilson from the University of California at Los Angeles. A 19th century method of police administration permanently ended along with a way of life that traded on the favors of politicians, organized crime, and ward heelers of the very worst stripe. The scandal known as "Summerdale" was of unprecedented magnitude. even for wicked old Cook County where malfeasance on the part of elected officials was (and by and large still is) just the normal course of doing the business of government. What made this one unique as opposed to the average run-of-the-mill shakedowns perpetrated against unsuspecting motorists pulled over for traffic violations was that for the first time in departmental history uniformed police officers plotted and carried out burglaries while patrolling the streets of the "City of Big Shoulders." Collecting bribes, expecting "presents" and other emoluments from retail merchants at Christmas time, was something that Chicago residents had come to expect of its police officers over the years. Burgling stores afterhours in the company of the accomplished sneak thief like Richard Morrison who often served as the "lookout," was quite another to the citizenry of Chicago. By the tender age of fifteen Morrison was well on the road to becoming a professional thief. His first arrest was recorded on May 6, 1953, when he was sentenced to ten days in the Cook County Jail for possessing burglar's tools. In the next two years his burgeoning criminal endeavors reflected a dozen different pick-ups as a burglary suspect. In December 1955, he shifted his operation to Los Angeles where he served nine months in prison for retail burglary. He then served nine months in Las Vegas for the same crime, before returning to Chicago in 1957 to accept a job delivering pizzas for Wesley's, at 1116 Bryn Mawr Avenue near Broadway. Morrison appeared to be settling in. Marriage was contemplated and his burglary tools were gathering dust. Police officers from the CPD's 40th District who were cognizant of his reputation, ticketed him for doubleparking his car outside of the pizza joint work place during rush hour. In an effort to persuade the officers to give Morrison, and the other drivers a "pass," the restaurant owner invited the police to come in and eat free. It was a common way for businessmen to befriend police who could be helpful to them by overlooking trivial matters or just being there when needed. At first the privilege was extended only to the sergeant and patrol officers assigned to Bryn Mawr Avenue. But eventually the enterprising Morrison was delivering pizzas directly to the 40th District, Foster Avenue—then known as "Summerdale." It was a convenient arrangement all around. The police officers on duty knew the glib Morrison from the neighborhood, and of course by reputation. A man can't escape from his past. Sol Karras, one of the Summerdale cops later named in the infamous indictment grew up with Morrison and maintained a friendship with him. In a short period of time Morrison had become one of Chicago's cleverest burglars. He learned about safes by visiting Michigan Avenue showrooms. He completed his apprenticeship by posing as a buyer of industrial safes and vaults in order to familiarize himself with the location of the tumblers, the thickness of steel, and the vulnerabilities of strong boxes. At all times he carried with him armor-piercing ammunition capable of blowing the locks off the most resilient safes. With manila rope purchased in 10,000-foot lengths, he fashioned rope ladders to help gain after-hours entry through the roof ventilation system and skylights. Morrison never used the same equipment twice. It was his personal quirk to leave his tools at the scene of the crime. James McGuire, a former Superintendent of the Illinois State Police, and a retired Chicago Police officer, remembers Morrison's escapades in the city and the North Shore suburb of Evanston. "He was a pretty sharp kid, a cocky little fellow who talked like an oldtimer. But he was just a kid...a kid, with exceptional abilities," McGuire recalls. "He liked to open the outer safe at a North Side Walgreens Store. That was one of his favorite places. There was usually $1,500 and loose change locked inside the safe, and he would stash the money nearby and pick it up the next day. Well, a suburban police officer caught him in the act one day going through an air vent. He handcuffed him to a telephone pole while he went off in search of a possible accomplice. The officer quickly returned after a look around but Richie was gone. He had used a secreted handcuff key taped to the back of a religious medal that he wore around his neck to escape." McGuire, an honest police officer whose career was on the upswing, was assisted by Chicago Detectives Howard Rothgery, Pat Driscoll, John Kettler, and James Heard from the burglary detail in their arrest of Morrison on the evening July 30, 1959 inside a flat on Sacramento Avenue while he was out on bond from an earlier pinch. As a result of an earlier arrest in the summer of 1958 by detectives from the adjacent suburban Evanston Police Department, the full story of Morrison's connivance with the "Summerdale" police officers unraveled ever so slowly. Morrison confessed to committing commercial burglaries with reported losses of over $100,000 in the City of Chicago alone. Looking back upon the Morrison collar, Jim McGuire states: "We got a tip he was holed up in this flat on Sacramento Avenue, but he wouldn't open the door. We found an open window and climbed through. When we entered Richie had a gun - a .38-caliber revolver - but he got scared and threw it down behind the refrigerator." There seemed to be no limit to the thieving escapades of Morrison, as investigators probed deeper into his exploits. His activities extended north of the city limits into Evanston. His second story jobs compromised the reputation of the entire police department of this city in a scandal that embarrassed the department and ultimately cost Chief Hubert G. Kelsh his job. Long before the scandal broke, in June 1958 to be exact, a detail of Evanston Police nearly killed Morrison during one of his nightly forays into the northern suburb. Retired Evanston Police Chief William McHugh and his former partner James Walsh (who later served as Chief of the Cook County Police Department) were a part of the response team that apprehended the thief forever known as the "Babbling Burglar." Several years ago, McHugh told this writer about his own personal encounter with Morrison. "We had a rash of automobile thefts in Evanston and the evidence pointed to Morrison." "Between relays during a target shoot at the practice range another policeman we knew who also happened to know Morrison told us that this was the guy who was hitting the hell of us in Evanston," added Walsh. "We concluded that this was our prime suspect and heard he was looking for a set of new golf clubs for his next score." McHugh, Walsh, along with Sergeant Sam Johnson, Officers Al Breitzman, Dick Braithwaite, and Eddie Tuczyinski, began a two-day stakeout on Forest Avenue, a quiet residential street off of Sheridan Road in Evanston late one evening. They used Officer Ted Arndt's set of new golf clubs as the decoy. "We figured that if Morrison was coming in to our town, this would be the route he would most likely travel," McHugh explains. The clubs were positioned in a station wagon on loan from a local automobile agency when the headlights of Morrison's mint-green Cadillac convertible were spotted by the detectives who were lying in ambush. Morrison was a skilled driver. He made a series of deft moves and the heavily armed Evanston officers made theirs, letting loose with a volley of gunfire from a shotgun and a Thompson sub-machine gun. The bullets flew wide of the mark. Morrison crouched down low in the car seat and spun away as the bullets whizzed by, striking the trees, parked cars, the curb—everything except their nimble criminal target. How badly did these Evanston cops want to kill Morrison? The deadly fury of bullets unleashed on a quiet residential side street in the dead of night endangered citizens, resulted in property damage, and was the kind of reckless police work out-ofcontrol departments often engaged in when they had something to hide. Fortunately for the "Babbling Burglar" fate intervened and he escaped unhurt. Shaken, Morrison abandoned the car on Sheridan Road in Chicago. "All we saw was his tail lights," McHugh recalls. "When he took off nobody could see him." McHugh and Walsh were a team in those days. Armed with a search warrant, they entered Morrison's apartment on Lakewood Avenue in the Rogers Park-Edgewater community looking for stolen contraband. "Little did we suspect at the time what Morrison was really up to," McHugh sighs. "We found a TV worth a small fortune and other expensive items strewn about the apartment." However, their man was not at home. When Walsh and McHugh returned a second time the apartment was "cleaned out," completely empty. "It was my belief that Richie received a tip from some of his friends in Summerdale that we were coming back," Walsh said. Walsh vividly remembered Morrison's cocky, defiant nature when they eventually located and transported him into the Evanston police station for interrogation and booking. "We asked him what he did for a living, and he told us that he was an 'electronics genius." 'That means I'm not a dumb asshole!' snorted the thief. Shortly afterward, the Morrison case came up for a hearing before Judge Charles Doherty in Branch 44 of the Felony Court at 26th and California. Again, Richard Morrison was apparently counting on his friends from the Summerdale police district to pull him out of a legal jam. He seemed confident that despite the serious charges stemming from his activities in Evanston, things would be "handled." The fix was in - or so Morrison was led to believe. Judge Doherty however, was of another frame of mind. He convicted the canny little burglar and sentenced him to two years in prison. "Hey! Wait a minute!" Morrison bellowed, casting about the courtroom for someone to listen. "Something is wrong here! I want to talk to the State's Attorney!" Snug inside the Cook County Jail, Morrison weighed his options. With the prospect of a lengthy prison sentence looming before him, he summoned representatives from the office of the Republican State's Attorney, Benjamin Adamowski, and told them that he had sensitive information to share about crooked cops in return for a deal—the customary promise of leniency. Negotiations continued with the public defender and Adamowski's right-hand man, Chief Investigator Paul Davis Newey from the State's Attorney's office, until Morrison finally agreed to be placed in a secret witness protection program. For the next fourteen months, the cat burglar enjoyed the comparative luxury of the County Jail witness quarters, complete with free TV, quality food, and special treatment accorded a valuable informant. Explained (then) Warden Jack Johnson: "If I put him in with the other prisoners I'll have a corpse on my hands within 24 hours. Ben Adamowski, a former Democratic politician who had his eyes on the bigger prize—the Chicago mayoralty—was slow to grasp the significance of the enormous political possibilities that lay before him. Others sensed that the impending Summerdale Scandal was a trump card to be played at all costs, and the best chance for the embattled Republicans to discredit the mayoral regime of the late Richard J. Daley. John D. Donlevy was a young Assistant State's Attorney assigned to Cook County's Criminal Division during the time when the imprisoned "Babbling Burglar" first began talking to prosecutors. "At first the State's Attorney Adamowski seemed reluctant to do anything. He just turned the matter over to a special prosecutor," Donlevy recalls. "There was a belief that the case wasn't strong enough to merit prosecution. Based on what Newey uncovered, "the decision was eventually made by Adamowski and First Assistant State's Attorney Frank Ferlic to bring it to trial." The episode in Evanston and the subsequent McHugh-Walsh arrest was one of the major catalysts triggering Summerdale. When Morrison realized that his "clout" was no good down at 26th and California and safely tucked away in the witness protection program, he began profusely talking about his relationship with crooked cops. He was dubbed the "Babbling Burglar" by the slightly jaded and cynical Chicago press corps. As the sordid tale of corruption unfolded, Evanston police officers were marched in one by one in by Adamowski and grilled about their relationship with Morrison and any ties the department might have had to the thief. In their possession the prosecutors had a damaging tape recording of Morrison discussing alleged payoffs made to Detective Chief "Ziggy" Wroblewski and Sergeant Bob Keyes. The payoffs were supposedly being made in order to help Morrison avoid an attempted burglary rap. Wroblewski was subsequently charged with obstruction of justice, but was cleared by Judge Duke Slater in a long-winded trial that tested the limits of everyone's patience. Criminal defense attorney Harry Busch, one of Chicago's infamously successful "mob mouthpieces" (a group that also included fellow "B&B Boys" Herb Barsay, Charles Bellows, Mike Brodkin and George Bieber) dragged file carts filled to overflowing with case law. Busch was preparing to filibuster the courtroom by citing each and every precedent on behalf of his client, just prior to a directed verdict of not guilty being handed down. "Ziggy" Wroblewski retired from the Evanston department a few years later and went to work with the American Packaging Corporation. Though he was never charged with a crime, Sergeant Keyes quit the department some years later to take a security job with the Orrington Hotel. "Morrison knew that anything he said about these officers would be construed as the gospel truth by the State's Attorney's office," Walsh strongly believed. "Clearly he was out to get even and was willing to destroy their careers in the process. Nailing a cop always gets headlines." Others saw matters differently, and the process of sweeping away the Evanston "questionables" was well underway. Chief Kelsh was "crucified in the press" according to McHugh's point of view and was replaced by Burt Giddons who was brought in from outside the department. Several Evanston Police officers who believed the department needed reforming went before the City Council to air their grievances. Kelsh was gone a short time later. Burt Giddons, possessing the ever powerful image of a reformer, sent a message that the days of collegiality between detectives, uniformed officers and underworld characters like Morrison was over. Like O.W. Wilson in Chicago (who was recruited as a desperation measure by a fretful Mayor Daley in the weeks following the Summerdale revelations), Giddons faced an uphill climb for respect. He ushered the Evanston P.D. into a new era until leaving the job in 1969. "Summerdale had a hell of an impact, not just the Chicago and Evanston Police Departments, but nationwide," McHugh sighed. "After the public became aware of Morrison's involvement with the cops, we would go into a restaurant and some wise guy would ask us where he could pick up a cheap TV. It was a profound embarrassment to the profession and we all suffered." In McHugh's day, few people viewed police work as a "profession," or took it seriously. "Very few officers attended college. There was no concerted effort to train and properly educate new officers. We were provided a notebook, a nightstick, and a hat shield by the department and told to hit the streets. We purchased our uniforms from the Fair Store in downtown Chicago, and we were assigned to work with a senior officer who disappeared most of the time," McHugh adds. Times changed and Summerdale began that process in Chicago. At the very heart of the unfolding Summerdale Scandal were eight patrol officers from the 40th District who were singled out for wrongdoing and prosecuted to the fullest extent of the law. Allan Brinn, Frank Faraci, Patrick Groark, Jr., Alex Karras and his twin brother Sol, Henry T. Mulea, Al Clements, and Peter Beeftink. These men came to symbolize all that the rottenness of the Chicago P.D. during that lamentable era, and a culture of corruption that had flourished since the mid-nineteenth century. These officers were the "Summerdale Eight" in the eyes of the media, though the involvement of Beeftink and Mulea was only marginal and there were many more officers from outlying districts who could have been just as deeply involved but were fortunate to escape detection. Groark was the son of a respected Chicago Police captain. Faraci, who was suspended once before for surrendering his weapon to a 16-yearold robber, lived outside the city limits in Skokie. By all accounts Faraci and the Karras twins were the ringleaders of the burglary gang. They acted as point men and scoped out the jobs by serving as lookouts while Morrison sabotaged alarm systems and broke into retail stores late at night. On one occasion, Morrison blatantly drove around the neighborhood in a marked squad car listening to the dispatch calls while two officers looted a store themselves. With the threat of snow hanging in the air, and the winter skies a leaden gray, Al Karras imagined himself sailing on his boat in the balmy Lake Michigan breezes of late spring. But first he had to have a new outboard motor, so he ordered Morrison to case the Anderson Marine Sports Supply Store on Broadway and report his findings back to the ring. It was a busy commercial area with many after-hours saloons and heavy foot traffic. Morrison was understandably apprehensive about making the score. Several months passed, and Karras was growing impatient. "Listen Dick, you've been stalling on Marine Supplies and spring is here now, and tonight you're going to open that place up for us!" Morrison and one of his partners named Floyd Wilde, agreed to smash the plate glass windows with a brick, but they refused to go inside. "You'll have to get the motors and whatever else you guys want because I don't want to be in that place with the front window broken out," he told them. Karras and Pat Groark carried the outboard motor through the shattered display window and no one was the wiser except of course, the smirking Morrison who could not believe the gall of these men. The Summerdale burglaries went on for a year and three months. Insurance premiums rose sharply for the merchants trying to conduct business in the stricken Edgewater neighborhood of Chicago. Numerous complaints were voiced to Captain Herman Dorf, commander of the 40th District, and (then) Chicago Police Commissioner Timothy O'Connor. Dorf was unwilling and did not lift a finger. He was counting the days to a carefree retirement. According to Morrison's sworn statements, Dorf had received a cut of the bribe money paid to Officers Glenn Cherry and John Peterson—the first of the crooked Summerdale cops to appear before a judge. During the subsequent investigation Captain Dorf refused to submit to a polygraph test. He handed in his resignation and said he was moving to California and would not be a party to any investigation that might draw him into the line of fire. Commissioner O'Connor was a figurehead appointee powerless to control the entrenched police bureaucracy of the City of Chicago. In the pre-Summerdale era, real policing power rested with the captains in the districts, and the politicians who backed them—not the Commissioner who knew only what he was suppose to know from his daily briefings from command personnel. The late Captain Frank Pape, who worked with O'Connor for many years, posed an interesting conundrum to this writer. "O'Connor was an honest man, but was he a moral man?" In other words, was his fear of punishment the overriding factor in the decision to resist graft, or could he possibly be corrupted if he were secure in the belief that he would not be caught? It was an amoral time and hundreds, possibly thousands of city and suburban police officers were on the take because of chronically low wages and poor working conditions. That however is not an acceptable alibi for acting in a manner contrary to the public good. The world that these men knew so well changed dramatically on January 15, 1960, when a team of detectives, hand-picked by Chief S.A. Investigator Paul Newey were given sealed orders directing them to the homes of the eight Summerdale burglars. They embarked on a mission that would rock the police and political world of Chicago to its knees. By 4:00 A.M. the next morning, the bleary-eyed cops were all under arrest and in custody, being secretly grilled by Adamowski's men inside the swank Union League Club. Walter Spirko, a veteran press reporter assigned to the police beat, maintained an all-night vigil at a nearby coffee shop where he was able to pry enough information out of the closed-mouthed investigators to break the story in the morning SunTimes. In the wake of Morrison's confession, the shocking arrest of the eight cop burglars, the impounding of thousands of dollars worth of stolen TVs, furniture, and recreational items, the canny Mayor Daley cast about for a scapegoat to take the fall. On January 23rd, Police Commissioner Tim O'Connor, by virtue of his position in the chain of command was forced to step down before he could be fired. "Tim was always telling me how he went home at night and watched TV instead of running around getting into trouble," Mayor Daley sneered. "I should have asked him why he wasn't running around checking on his policemen at night instead of sitting home and watching TV." It was good political posturing and a crafty public statement coming from a man who knew the system and played it like the political pro he was. For perhaps the only time in his political career, Richard J. Daley found himself in a precarious position and in serious jeopardy of relinquishing City Hall to the Republicans and the eternally ambitious Adamowski. The next mayoral election was still three years away, but Republican Governor, William Stratton, in lockstep with the Cook County Republican State's Attorney, at last had a boilerplate issue to lay before disgruntled voters. It was one that would not disappear with a simple wave of the politician's pinky-ring finger, or through the application of colorful Daleyesque rhetoric. The Republicans knew they had their chance and they moved forward with dispatch. Since the Civil War, succeeding Chicago Mayors would answer the clamor of the reformers by shuttling the offending district commanders and inspectors to outlying areas of the city following a damaging frontpage expose of malfeasance. After the usual reprimands and suspensions were doled out, things would generally quiet down and the department would return to its pre-scandal levels...until next time. It was a laissez-faire atmosphere the politicians sanctioned in order to keep control of their patronage and placate constituents at the same time. Summerdale, however, required much more than the usual approach. Daley understood the hazardous political realities and appointed a blueribbon panel to step outside the inner circle of his administrators, ward committeemen, and the entrenched 11th Ward police cadre to select a new Police Commissioner who would lend an air of professionalism, scholarship, and a hard-edged approach to law enforcement. Orlando W. Wilson, Dean of Criminology and professor of police administration at the University of California was named to chair the blue-ribbon screening committee which also included William L. McFetridge of the Chicago Federation of Labor, and Franklin W. Kreml, director of the prestigious Northwestern Traffic Institute in Evanston, whose police department was as badly tarnished as Chicago. It was one of the few academic institutions in the nation offering courses in criminal justice at this time. During the early rounds of committee deliberations, Franklin Kreml emerged as a possible contender for the top post himself. Mayor Daley however, acted on the advice of Fred Hoehler, Superintendent of the old House of Correction, who urged him to bring the astute clean as a whistle outsider Wilson in to oversee the ad hoc committee. Hoehler was well familiar with Wilson's background, and the new approach ideas illuminated in his book Police Administration, which was the standard textbook of the law enforcement profession of the time. Wilson's book provided commentary on the future needs of police management in an ever changing, complex field—that which we call metropolitan police work. It soon became clear that Wilson had enjoyed the inside track all along for the top police job, and the process of interviewing other candidates for the job now to be known as Superintendent of Police was merely pro forma. On February 22, 1960 with the political playing field leveled in favor of only one man, Daley announced to the city that Wilson was the unanimous choice of the committee to become the city's reform police leader. The designation of "Commissioner" was dropped in order to break with the past litany of scandal. Wilson, with the revived 19th Century title of Superintendent applied, received a three-year contract and the assurance of non-interference from City Hall as his conditions for taking the job. He was also granted wide latitude and the money that was always withheld in the past from City Hall that none of his predecessors had ever received, to complete overdue tasks. O.W. Wilson took over a department grounded in archaic 19th century policing methods, and one that was very hostile to "outsiders" and "experts" who would integrate "college theories" into a tough profession dominated for the most part by ethnic Irish and Germans who came up the hard way fighting their battles in the mean streets of Chicago. The thin, angular, hard-drinking, chain-smoking Norwegian encountered fierce resistance to his plan of re-organization. But within a few years Wilson had earned the grudging admiration of the rank-and-file because they discovered that here was a man who they perceived as playing the game fair and was not shackled by the usual political drag. For the first time in years, competitive sergeants exams were held, and at last a chance for qualified officers to receive promotions long overdue. The centerpiece of the Wilson reforms was the formation of an Internal Investigations Division, otherwise known as the I.I.D. The creation of a unit to "police the police" was pushed forward by Virgil W. Peterson, then the Executive Director of the Chicago Crime Commission. But even Peterson, whose opinions carried great weight in legislative circles, couldn't see it through until after Summerdale parted the political waters. The rank-and-file street cops and their political sponsors fiercely resisted the idea of what they considered a "spy network" evolving within the department. Summerdale changed the absurd notion that shielded official corruption. In the intervening four decades, we have witnessed only a handful of the kinds of damaging corruption scandals involving groups of police officers conspiring to collect bribes or commit shakedowns that plagued Chicago on repetitive cycles in former times. Wilson championed police technology. He moved his office out of City Hall and into Police Headquarters (then located at 11th and State), signaling his intention to remain independent of politics. Wilson built an expensive communications center to expedite handling of emergency calls. He encouraged two-way dialog between the administration and the men by way of face-to-face meetings or personal memoranda, a procedure called "PAX 501." Patrol officers who had walked their beat in city neighborhoods since time immemorial were provided with two-man squad cars in order to cover more ground in half the time. In this instance it is fair to say that Wilson probably miscalculated the effectiveness and long-term consequences of such a change. The vaunted "CAPS" program instituted by Superintendent Matt Rodriguez in the mid-1990s, (launched in twenty-five Chicago districts initially) is a variation of the old cop on the beat method of patrol which existed for more than a hundred years before Wilson's ideas and book theories set the pace for police administrations across the country. The modernization of the Chicago Police Department was a costly, sometimes laborious process consuming much of the resources and time of the Wilson administration that ended with his well-timed retirement in 1967. O.W. left a tough job virtually unscathed. Assessing the impact of these changes from the vantage point of history, most police observers agree that O.W. was a positive force for change. "From that standpoint the city benefited tremendously," said John Donlevy, one of the Summerdale prosecuting attorneys. "Wilson made this truly a profession," commented William Hanhardt, discredited former Chicago Police Department Deputy Superintendent who is trying to crawl out from under the cloud of a Federal indictment for his alleged role in an interstate jewelry theft ring. In better days, Hanhardt led the C.I.D. burglary investigations unit. "He removed 80% of the politics from the police department. If you could do the job no one could take it away from you under Wilson. He was a God-send who surrounded himself with some of the smartest people in the field of law enforcement." Jim McGuire agreed with Hanhardt. "One day we street cops were no good thieves. Then thanks to Wilson, the public's perception changed and we became terrifically sharp crime busters. He did so many things that weren't in the cards before. He called for much needed raises in our salaries. Promotional exams were scheduled. There had not been a sergeant's exam in 12 years. Before Wilson we did what the pols told us," McGuire recalls. "In those first few years there was no captain in Chicago who dared to push us around the way they had become accustomed to. Wilson gave us the opportunity to do our job and be policemen." In the counter-opinion of James Walsh, Superintendent Wilson was only a "mixed blessing." "He came out of academia. His heart was in the right place, but he didn't have any practical exposure on the streets. He did not fully understand situations as they applied to the big cities. He was a book cop." The first round of cases involving crooked policemen reached the courts in November 1960, exactly 11 months after the late Sun-Times reporter Water Spirko broke his page one exclusive that a group of crooked North Side cops were in league with a cat burglar named Richard Morrison. The prosecution of Officer John Peterson and Detective Glenn Cherry was conducted by Assistant States Attorneys Louis Garippo and John Donlevy, and it was heard before Judge Daniel A. Covelli. The two Summerdale officers were charged with conspiring, for money, to help Morrison beat a minor burglary rap. The key prosecution evidence was a Polaroid camera stolen by Morrison and his henchman Gerald Bossyut from a North Side auto agency. The indictments charged Peterson and Cherry with obstruction of justice and conspiracy. They had switched a legitimately purchased camera for the stolen one in the police custodian's office to nullify the evidence against Morrison. In return Morrison paid them a $400 bribe. At issue all throughout the trial was Richard Morrison's credibility. He took the 5th Amendment thirty-two times and hesitated before answering every question. "I thought we a had a good winnable case," Donlevy explained. "At first we didn't think the jury would accept Morrison's word against the two police officers, but if we could establish other circumstances then we could win." As it turned out, neither Cherry nor Peterson stood up well under crossexamination. The jury convicted both men on the second ballot. Peterson was sentenced to nine months in prison. Cherry was slapped with a $500 fine. Commenting on these developments, the Chicago Sun-Times called on the police department to clean up its own house. "The police department should be able, on its own, to produce evidence against its erring members that will stand up in court. Under Superintendent O.W. Wilson, such self-policing now is under way. Selfpolicing is the ounce of prevention that makes unnecessary the pound of police officer Chicago is paying for." Unfortunately the Cherry-Peterson case was only round one on the arduous path toward reform. The apprehensive police officers had good reason to fear what he might reveal next, while Morrison made sure that he received something in return. The carrot Adamowski dangled in front of Morrison was the state's promise to drop 20 charges of burglary in return for his full cooperation in court. The diminutive thief kept right on talking. The confession filled 77 pages, and it was considered solid evidence to be used against the other eight Summerdale officers when that case finally opened in the courtroom of U.S. District Judge James B. Parsons on June 26, 1961. Louis Garippo, assisted by Charles Rush, Daniel McCarthy, and Barnabas Sears led for the prosecution. The flamboyant Julius Lucius Echeles and Charles Bellows of "B&B Boys" fame based their entire defense on the unreliability of Richard Morrison and his willingness to say anything in order to save his neck. The defendants were found guilty by the all-female jury after two months of heated courtroom testimony. Judge Parsons sentenced Clements, Faraci, and Alex Karras from two-to-five years; Sol Karras received two to three years. Allan Brinn, who aroused the sympathy of the jury after it was revealed that he had "saved" Morrison from death by warning him that the same Summerdale cops were contemplating his murder, was ordered to serve one to three years; Beeftink and Mulea were let go with $500 fines. Pat Groark, who steadfastly maintained his innocence asked for a bench trial. He received six months in prison, served his time, and returned to civilian life. He was accidentally killed in a Lake Michigan boating mishap a few years later. The tragedy scarred his family, one with a long police tradition. Groark was the only one of the eight to serve any jail time. The appeals dragged on for a full six years before the sentences were quietly overturned. By the late 1960s, Vietnam, the Civil Rights movement, and the youth counter culture were in full flower. The final resolution of the Summerdale cases was yesterday's news, and was given little notice by the local media. The story had run its course. The indirect role Richard Morrison played in Wilson's appointment and all that was to follow cannot be discounted. The little thief was the stimulus of powerful change, and if he is still alive today he must surely reflect back on this period of time with a sense of irony and benign amusement. Morrison survived machine gun bullets in Evanston and an assassination attempt outside the Criminal Courts Building in 1962 that many of the old timers maintain was planned and carried out by a hit team of disgruntled cops. The "Babbling Burglar" relocated to Florida following the conclusion of the second Summerdale trial in 1961, but was brought back to Chicago and was preparing to testify in a related case when a vicious shotgun blast from a passing automobile tore through his arm. With his luck still holding strong, he survived the hit. When the ambulance pulled up to the curb at 26th and Cal, he pleaded with the driver not to leave him alone with the police officers on the scene. Morrison was rushed to the hospital in the company of his attorney. He feared the possibility that other Chicago cops would finish what the unknown gunman had failed to deliver. No one who was connected in any way with the Morrison case can say with moral certainty just what happened to the "Babbling Burglar" after the last of the Summerdale hearings were consigned to the dust heap of history. Rumors continue to circulate that he went to work as a police photographer in Fort Lauderdale, but got into some unspecified "trouble" back in the 1960s. The suggestion has also been put forth that he entered into the witness protection program and has assumed a new identity. Whatever the case, Richard Morrison will never be forgotten by those who lived through the epic of Summerdale. Despite an overall improvement in efficiency and morale, the repercussions of this historic scandal continue to be felt forty-plus years later. The indictment of William Hanhardt for his alleged involvement with a crew of jewelry thieves nominally tied to the Outfit; the cloud of scandal that hung over the head of former Superintendent Matt Rodriguez who stepped down as a result of his friendship with a reputed mob figure on the North Side; shakedown scandals out in the Austin District; accusations of brutality and the shootings of unarmed civilians by uniformed patrol protected to the bone by attorneys from the police union, all suggest that the department might be better served with the appointment of an independent outsider, the caliber of an Orlando W. Wilson; someone free from the corrupting political drag of Chicago's Democratic patronage machine. That is not likely to happen anytime soon, not in Chicago where the watchword has always been "Don't make no waves! We don't want nobody sent!" The most important lesson from the Summerdale affair was that the police star could no longer be considered as a badge of immunity or a license to steal, but is anyone still listening?