Red Wine Varieties for the northern parts of eastern North America

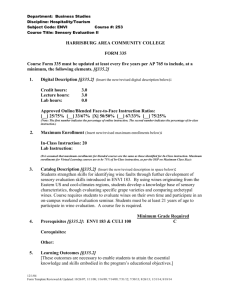

advertisement

“New” Red Wine Varieties for Trial in the Northern Parts of Eastern North America Bob Pool Department of Horticultural Sciences Cornell University Geneva, NY 14456 In 1964, when wine grape research became “officially” acceptable and even encouraged at Cornell’s Geneva experiment station, 80% of table wine consumption in the U.S. was red. The primary goal of the new program was to create or identify varieties that would make better red table wines than were obtained using the traditional Native American varieties. At that time, a de facto testing group had already been testing new varieties, mostly hybrid ones, for use in eastern North America. In addition to John Einset and Willard Robinson of the station, this group included such names as Phillip Wagner, Charles Fournier, Ed Haynes, A. DeChaunac, Ollie Bradt and other American and Canadian leaders of the effort to transform our industry from the production of sweet dessert wines to main stream table wines. That effort identified many varieties now industry standards including DeChaunac, Baco Noir, Chancellor and others. During the last half of the 1960’s very palatable red wines were being produced in the east using these varieties. However, as demand outpaced supply, growers found they could sell inferior grapes from overcropped vines. The result was that in the early 1970’s red wine quality declined precipitously and sales fell in response. The hybrids, formerly looked upon as the salvation, became a curse. It is somewhat ironic that by 1970, not only had U.S. table wine consumption increased almost 10 fold, nearly all the increase was in white wines. The interest in new red wine varieties for the east disappeared. Perhaps for that reason, the first product of Cornell’s new wine grape program was Cayuga White, introduced in 1972. In 1974 when I took over the grape-breeding program, I was asked by the 29th Annual New York Wine Industry Workshop 31 station director, “When can we expect the new red varieties promised when the program was started.” An industry member answered for me; “the last thing we want is more red hybrids.” After that the problem wasn’t so much working with white wine varieties, but persuading administrators to continue to support a balanced program of red and white wine grape breeding. The pendulum has now swung once more. Advances in regional winery sophistication, population demographics, increasing consumer sophistication and health news have combined to renew the interest in red wines. Once again we are asked to identify varieties to meet the changed markets. There are really two separate markets, the mass market and the emerging “ultra” premium market. The two segments have different needs. The following discussion is based on my personal opinions. These comments should all be taken as preliminary. On the other hand, if you want exact knowledge, you will have to wait until these varieties are no longer “new”. Mass Market Red Wine Varieties Much of the new interest in red wine is coming from people who are not already red wine drinkers. These consumers have heard that red wine is good for you, but may not be familiar with or ready for a “big” red wine of character. The wine should be pleasant, but not too assertive. Perhaps a little residual sugar will not detract from acceptance. Neither the grape nor the wine producer should expect to get top dollar from this market. The grapes should be widely adapted, and not require above average vineyard inputs to succeed. Named Hybrids: Chambourcin – this is not really a new variety, but it has not been widely grown in New York. Personally, I am still not enthusiastic about it for our region, but the vine has moderate cold hardiness and, when the grapes ripen, the wines are good. The drawbacks are that the hardiness is not all that great (for a hybrid) and too often 29th Annual New York Wine Industry Workshop 32 the grapes do not fully ripen in our climate. Unripe Chambourcin makes herbaceous, not very interesting wines. St. Croix – I really do not have much personal knowledge about the variety. It seems to grow like a weed in New York, and the wines I have had from Missouri have been pleasant. Check with others before planting. Hybrids not yet named The breeding effort of the 1960’s and 1970’s may be finally producing pay back. Dr. Bruce Reisch and Dr. Thomas Henick-Kling have identified two selections for advanced testing. These may be released sooner rather than later. They can already be purchased from the Grafted Grapevine Nursery under special license. (The comments below were taken directly from Dr. Reisch’s web site. I have tasted the wines and find them equal or superior to the hybrids presently available) NY70.0809.10 - (SV 18-307 x Steuben) - produces a highly ranked vinous, vinifera type wine. The vine is vigorous and very productive at Geneva. Some cluster thinning is usually required to avoid overcropping. Vines are healthy with good powdery mildew and Botrytis rot resistance and often maintain green leaves up until frost. Fruit maturity is late, with harvest Oct. 15-20 in Geneva. NY73.0136.17 - [(NY33277 x Chancellor) x Steuben] produces an excellent full-bodied wine with a distinct pepper character and moderate tannin content. Vines have generally been vigorous and productive in the Finger Lakes of New York, though older vines occasionally show a slow decline in vigor that may be indicative of a need for grafting. The leaves show moderate resistance to powdery mildew, but both fruit and leaves require a regular spray program to control downy mildew. Fruit maturity is mid-season, approx. Oct. 1 in Geneva. (These comments are my own and do not necessarily reflect the views of Dr. Reisch) 29th Annual New York Wine Industry Workshop 33 GR7 – This is one of the oldest selections in the Geneva grape breeding program. It has been tested widely in commercial Finger Lakes vineyards. It is an exceptionally well adapted variety. It is very productive, cold hardy and lends itself to mechanized production. The wine is not exceptional. In fact the wines are somewhat thin and have only moderate flavor. They sometimes have a slight American (Labrusca) aroma. However, the wines are very well received in the standard quality market. Because of the remarkable vineyard adaptation, I would like to see this vine made available to growers. While the wine quality is only average, growers in lower quality sites will be able to produce grapes, which presently have a good market. 29th Annual New York Wine Industry Workshop 34 Less widely planted vinifera varieties Table 1 is reproduced from a research report prepared by Thomas Henick-Kling and me. It is a list of non-standard varieties we have been testing. The above varieties have produced some interest. Dornfelder – this is a “new” variety from Germany produced to make wine with better color than most German reds attain. The variety has been very easy to grow, productive and hardy. We have only made a few wines and these have ranged from acceptable to good. The wine is pleasant rather than impressive. It would probably be best marketed to main stream consumers who will pay a premium for vinifera wine. Petit Verdot – This is one of the authorized varieties for Bordeaux blends in France. We have had long experience with it in Geneva. It ripens with Cabernet Sauvignon, and I see little reason to plant it except when wine makers want to increase the complexity of his/her Meritage blend. Table 1. Mean median low temperature exotherm temperature for primary buds from various red wine Vitis vinifera grape varieties (January 1999). Variety Dornfelder Petit Verdot Malbec Trollinger Lemberger Pinotage Shiraz Gamay Noir Mean median low temperature exotherm (F) -13.3 -12.5 -11.8 -11.2 -10.2 -8.7 -8.1 -6.9 Malbec – This is supposedly the most widely planted red wine variety in France (mostly grown under the name, Côt). We really do not have all that much experience with the variety or its wine, but our experiences have been pleasant so 29th Annual New York Wine Industry Workshop 35 far. I can only recommend for experimental planting. Though 100% Malbec wines from South America and Australia are accpetable to good in quality—not outstanding. Trollinger – is grown in Germany where it is often blended with Lemberger. It seems to be reasonably cold hardy. The wine is light and fruity rather than big and complex. Sometimes the color is more like a rose than a red. The wine has very attractive fruit aromas and a lively palate. Pinotage – is a new variety from South Africa. It was produced from the cross, Pinot Noir X Cinsault. The vine performance is similar to Pinot Noir. Probably the only reason to grow it is to have a unique wine to personally market. Shiraz (Sirah) – this is the Australian clone of Syrah. As a Rhone variety, we would expect low cold hardiness. To date we have not had severe injury and the wines have been impressive. Again, plant only as an experiment. Gamay Noir – this is the variety of Beaujolais and parts of Burgundy. It produces a wine similar to, but less impressive than, Pinot noir. It will easily overcrop. Personally, I would plant Pinot noir until I had too much to sell. Then I might consider Gamay noir. Still it seems about as easy to grow as Pinot noir and makes very pleasant, fruity wines. It might have interest as a true premieur variety. Lemberger - 29th Annual New York Wine Industry Workshop 36