The Allon plan via the road map?, The Jerusalem Post, June 8, 2003.

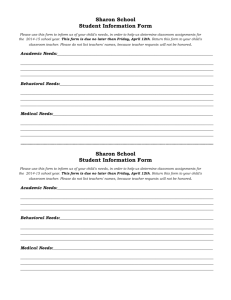

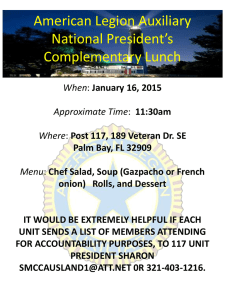

advertisement

THE JERUSALEM POST, 8 JUNE 2003 The Allon Plan via the road map? Efraim Inbar Prime Minister Ariel Sharon has usually been regarded as an ideologue of the Greater Land of Israel and is often credited with being a main force in the Israeli settlement activities in Judea, Samaria and Gaza. He had a reputation for being an arch-hawk with a proclivity to use military force to achieve his goals, which was demonized by the Israeli Left and by the international press. This is beginning to change. In recent months, and particularly after the Sharon-led government accepted the road map, many have been asking whether a new Sharon has emerged. It is naïve to believe that Sharon has undergone a metamorphosis. Sharon has always been a pragmatic hawk who was skeptical of Arab intentions and very sensitive to security considerations. Analogies to De Gaulle or Gorbachev are misguided. Actually, Sharon compares favorably to his friend Yitzhak Rabin (the true, not the mythological), and to Yigal Allon (a Laborite leader). Indeed, Sharon’s sociopolitical roots are in the activist camp of the Labor movement that brought to the fore Allon and Rabin, but disappeared. Whatever preferences Sharon had in the past, his pragmatic streak leads him to try to implement a version of the Allon Plan (broadening the narrow waist of Israel within the pre-1967 borders, annexing the strategically situated Greater Jerusalem, as well as the security belt of the Jordan Rift). The Allon Plan was for a while associated with mainstream Israeli politics. Yet, over the past 30 years, Israel has seen the center of its politics moving leftwards, only to realize in October 2000 that a rightward corrective is much needed. With the adolescent peace euphoria over, a more mature mood emerged, allowing the strategic and demographic rationale of Allon’s Plan to regain its relevance. The suspicious Israeli public accepts territorial concessions, including the dismantlement of some settlements, but in light of the unreliability and the basic hostility of the Palestinian neighbors, it insists on large margins of security in spatial and temporal terms in future agreements. Nowadays, Sharon reflects and voices this centrist mood. He epitomizes the center of Israeli politics, which became closer to his intuitive political positions. His centrist hawkishness explains his popularity among the Israelis. This is why he won decisively two consecutive elections and why he gets a high rate of approval for his performance as prime minister. A recent example of Sharon’s centrism is his acceptance of the road map – a very problematic document for Israel. Indeed, according to a Dahaf poll, 62% of the Israelis believed he surrendered to an American dictate; nevertheless, 56% thought it was wise to do so, despite the fact that, according to another poll, more than two-thirds of the Israeli public doubt the road map will bring about peace. Sharon’s strategy toward the Arab-Israeli conflict is based upon two central tenets. The first element is a continuous demonstration of a determination to seek peace. Sharon reiterated his willingness to make “painful concessions” to further peace negotiations. For example, he accepted the Mitchell, Tenet, and Zinni plans, as well as the road map - all American-sponsored initiatives. At the end of his political career, his attempts to reach a stable agreement, one that he would like to be remembered for, have a ring of credibility. Gradually, we see Arabs grasping that Sharon might be serious about peace making. Sharon also understands that a widespread realization of the sincerity of the leadership’s policy to bring about a reasonable agreement constitutes a prerequisite for maintaining the social cohesion in Israeli society that is needed for the protracted conflict ahead. If the road map leads nowhere and the violent conflict with the Palestinians will continue at oscillating levels – a probable scenario – Israeli society must be ready. The second component of his strategy is the American orientation. Sharon is keen on maintaining good relations with the US, the hegemonic power in the 21st century. It is Israel’s major military, diplomatic and economic supporter and Sharon was successful in coordinating positions with Washington. Such coordination remains an Israeli goal even after the war in Iraq, which eased Israel’s strategic situation, because existential threats have not been entirely removed. Iran still pursues the option to build nuclear weapons. North Korean nuclear technology may be exported to Israel’s enemies in the region. The Israeli defense establishment has realized that unilateral Israeli steps are not enough to meet challenges of such a magnitude. Parrying them requires American diplomatic, military, technological, financial and diplomatic support. Sharon realizes the critical role of the US for Israel’s national security and has therefore shown his reluctance to estrange Washington time and again. So far, the Palestinian extremism has spared Sharon any serious challenges to his well-crafted strategy. While this trend is likely to continue, Sharon may face greater international and domestic pressures for unilateral concessions that might create grave security risks. Moreover, the road map is not conducive to the realization of the Allon Plan. It remains to be seen how Sharon will be able to maneuver to maintain substantial national consensus and American friendship without compromising Israel’s long-range security.