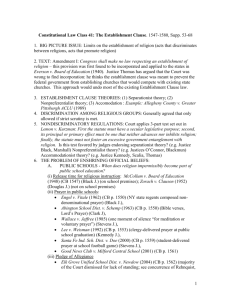

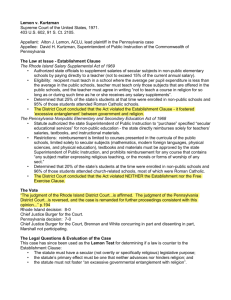

Wallace v. Jaffree - Patrick Henry College

advertisement