Colonialism1 - to connect to our mail system using your web

advertisement

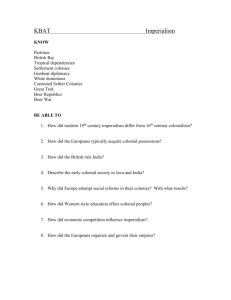

19th Century Colonialism I: The New Imperialism Going up that river was like traveling back to the earliest beginnings of the world, when vegetation rioted on the earth and the big trees were kings. An empty stream, a great silence, an impenetrable forest. The air was warm, thick, heavy, sluggish. There was no joy in the brilliance of sunshine. The long stretches of the waterway ran on, deserted, into the gloom of overshadowed distances. On silvery sandbanks hippos and alligators sunned themselves side by side. The broadening waters flowed through a mob of wooded islands; you lost your way on that river as you would in a desert, and butted all day long against shoals, trying to find the channel, till you thought yourself bewitched and cut off for ever from everything you had known once--somewhere--far away--in another existence perhaps. There were moments when one's past came back to one, as it will sometimes when you have not a moment to spare to yourself; but it came in the shape of an unrestful and noisy dream, remembered with wonder amongst the overwhelming realities of this strange world of plants, and water, and silence. And this stillness of life did not in the least resemble a peace. It was the stillness of an implacable force brooding over an inscrutable intention. It looked at you with a vengeful aspect. I got used to it afterwards; I did not see it any more; I had no time. I had to keep guessing at the channel; I had to discern, mostly by inspiration, the signs of hidden banks; I watched for sunken stones; I was learning to clap my teeth smartly before my heart flew out, when I shaved by a fluke some infernal sly old snag that would have ripped the life out of the tin-pot steamboat and drowned all the pilgrims; I had to keep a look-out for the signs of dead wood we could cut up in the night for the next day's steaming. When you have to attend to things of that sort, to the mere incidents of the surface, the reality--the reality, I tell you--fades. The inner truth is hidden--luckily, luckily. But I felt it all the same; I felt often its mysterious stillness watching me at my monkey tricks, just as it watches you fellows performing on your respective tight-ropes for--what is it? half-a-crown a tumble----" "Try to be civil, Marlow," growled a voice, and I knew there was at least one listener awake besides myself. "I beg your pardon. I forgot the heartache which makes up the rest of the price. And indeed what does the price matter, if the trick be well done? You do your tricks very well. And I didn't do badly either, since I managed not to sink that steamboat on my first trip. It's a wonder to me yet. Imagine a blindfolded man set to drive a van over a bad road. I sweated and shivered over that business considerably, I can tell you. After all, for a seaman, to scrape the bottom of the thing that's supposed to float all the time under his care is the unpardonable sin. No one may know of it, but you never forget the thump--eh? A blow on the very heart. You remember it, you dream of it, you wake up at night and think of it--years after--and go hot and cold all over. I don't pretend to say that steamboat floated all the time. More than once she had to wade for a bit, with twenty cannibals splashing around and pushing. We had enlisted some of these chaps on the way for a crew. Fine fellows--cannibals--in their place. They were men one could work with, and I am grateful to them. And, after all, they did not eat each other before my face: they had brought along a provision of hippo-meat which went rotten, and made the mystery of the wilderness stink in my nostrils. Phoo! I can sniff it now. I had the manager on board and three or four pilgrims with their staves--all complete. Sometimes we came upon a station close by the bank, clinging to the skirts of the unknown, and the white men rushing out of a tumble-down hovel, with great gestures of joy and surprise and welcome, seemed very strange,--had the appearance of being held there captive by a spell. The word ivory would ring in the air for a while--and on we went again into the silence, along empty reaches, round the still bends, between the high walls of our winding way, reverberating in hollow claps the ponderous beat of the stern-wheel. Trees, trees, millions of trees, massive, immense, running up high; and at their foot, hugging the bank against the stream, crept the little begrimed steamboat, like a sluggish beetle crawling on the floor of a lofty portico. It made you feel very small, very lost, and yet it was not altogether depressing that feeling. After all, if you were small, the grimy beetle crawled on-which was just what you wanted it to do. Where the pilgrims imagined it crawled to I don't know. To some place where they expected to get something, I bet! For me it crawled towards Kurtz--exclusively; but when the steam-pipes started leaking we crawled very slow. The reaches opened before us and closed behind, as if the forest had stepped leisurely across the water to bar the way for our return. We penetrated deeper and deeper into the heart of darkness. It was very quiet there. At night sometimes the roll of drums behind the curtain of trees would run up the river and remain sustained faintly, as if hovering in the air high over our heads, till the first break of day. Whether it meant war, peace, or prayer we could not tell. The dawns were heralded by the descent of a chill stillness; the wood-cutters slept, their fires burned low; the snapping of a twig would make you start. We were wanderers on a prehistoric earth, on an earth that wore the aspect of an unknown planet. We could have fancied ourselves the first of men taking possession of an accursed inheritance, to be subdued at the cost of profound anguish and of excessive toil. But suddenly, as we struggled round a bend, there would be a glimpse of rush walls, of peaked grass-roofs, a burst of yells, a whirl of black limbs, a mass of hands clapping, of feet stamping, of bodies swaying, of eyes rolling, under the droop of heavy and motionless foliage. The steamer toiled along slowly on the edge of a black and incomprehensible frenzy. The prehistoric man was cursing us, praying to us, welcoming us--who could tell? We were cut off from the comprehension of our surroundings; we glided past like phantoms, wondering and secretly appalled, as sane men would be before an enthusiastic outbreak in a madhouse. We could not understand, because we were too far and could not remember, because we were traveling in the night of first ages, of those ages that are gone, leaving hardly a sign--and no memories. The earth seemed unearthly. We are accustomed to look upon the shackled form of a conquered monster, but there--there you could look at a thing monstrous and free. It was unearthly, and the men were ---- No, they were not inhuman. Well, you know, that was the worst of it--this suspicion of their not being inhuman. It would come slowly to one. They howled, and leaped, and spun, and made horrid faces; but what thrilled you was just the thought of their humanity--like yours--the thought of your remote kinship with this wild and passionate uproar. Ugly. Yes, it was ugly enough; but if you were man enough you would admit to yourself that there was in you just the faintest trace of a response to the terrible frankness of that noise, a dim suspicion of there being a meaning in it which you--you so remote from the night of first ages--could comprehend. And why not? The mind of man is capable of anything-because everything is in it, all the past as well as all the future. What was there after all? Joy, fear, sorrow, devotion, valour, rage--who can tell?--but truth--truth stripped of its cloak of time. Let the fool gape and shudder--the man knows, and can look on without a wink. But he must at least be as much of a man as these on the shore. He must meet that truth with his own true stuff--with his own inborn strength. Principles? Principles won't do. Acquisitions, clothes, pretty rags--rags that would fly off at the first good shake. No; you want a deliberate belief. An appeal to me in this fiendish row--is there? Very well; I hear; I admit, but I have a voice too, and for good or evil mine is the speech that cannot be silenced. Of course, a fool, what with sheer fright and fine sentiments, is always safe. Who's that grunting? You wonder I didn't go ashore for a howl and a dance? Well, no--I didn't. Fine sentiments, you say? Fine sentiments be hanged! I had no time. I had to mess about with white-lead and strips of woollen blanket helping to put bandages on those leaky steam-pipes--I tell you. I had to watch the steering, and circumvent those snags, and get the tin-pot along by hook or by crook. There was surfacetruth enough in these things to save a wiser man. And between whiles I had to look after the savage who was fireman. He was an improved specimen; he could fire up a vertical boiler. He was there below me, and, upon my word, to look at him was as edifying as seeing a dog in a parody of breeches and a feather hat, walking on his hind-legs. A few months of training had done for that really fine chap. He squinted at the steam-gauge and at the water-gauge with an evident effort of intrepidity--and he had filed teeth too, the poor devil, and the wool of his pate shaved into queer patterns, and three ornamental scars on each of his cheeks. He ought to have been clapping his hands and stamping his feet on the bank, instead of which he was hard at work, a thrall to strange witchcraft, full of improving knowledge. He was useful because he had been instructed; and what he knew was this--that should the water in that transparent thing disappear, the evil spirit inside the boiler would get angry through the greatness of his thirst, and take a terrible vengeance. So he sweated and fired up and watched the glass fearfully (with an impromptu charm, made of rags, tied to his arm, and a piece of polished bone, as big as a watch, stuck flatways through his lower lip), while the wooded banks slipped past us slowly, the short noise was left behind, the interminable miles of silence--and we crept on, towards Kurtz. But the snags were thick, the water was treacherous and shallow, the boiler seemed indeed to have a sulky devil in it, and thus neither that fireman nor I had any time to peer into our creepy thoughts. Some fifty miles below the Inner Station we came upon a hut of reeds, an inclined and melancholy pole, with the unrecognizable tatters of what had been a flag of some sort flying from it, and a neatly stacked wood-pile. This was unexpected. We came to the bank, and on the stack of firewood found a flat piece of board with some faded pencil-writing on it. When deciphered it said: 'Wood for you. Hurry up. Approach cautiously.' There was a signature, but it was illegible--not Kurtz--a much longer word. Hurry up. Where? Up the river? 'Approach cautiously.' We had not done so. But the warning could not have been meant for the place where it could be only found after approach. Something was wrong above. But what--and how much? That was the question. We commented adversely upon the imbecility of that telegraphic style. The bush around said nothing, and would not let us look very far, either. A torn curtain of red twill hung in the doorway of the hut, and flapped sadly in our faces. The dwelling was dismantled; but we could see a white man had lived there not very long ago. There remained a rude table--a plank on two posts; a heap of rubbish reposed in a dark corner, and by the door I picked up a book. It had lost its covers, and the pages had been thumbed into a state of extremely dirty softness; but the back had been lovingly stitched afresh with white cotton thread, which looked clean yet. It was an extraordinary find. Its title was, 'An Inquiry into some Points of Seamanship,' by a man Tower, Towson-some such name--Master in His Majesty's Navy. The matter looked dreary reading enough, with illustrative diagrams and repulsive tables of figures, and the copy was sixty years old. I handled this amazing antiquity with the greatest possible tenderness, lest it should dissolve in my hands. Within, Towson or Towser was inquiring earnestly into the breaking strain of ships' chains and tackle, and other such matters. Not a very enthralling book; but at the first glance you could see there a singleness of intention, an honest concern for the right way of going to work, which made these humble pages, thought out so many years ago, luminous with another than a professional light. The simple old sailor, with his talk of chains and purchases, made me forget the jungle and the pilgrims in a delicious sensation of having come upon something unmistakably real. Such a book being there was wonderful enough; but still more astounding were the notes penciled in the margin, and plainly referring to the text. I couldn't believe my eyes! They were in cipher! Yes, it looked like cipher. Fancy a man lugging with him a book of that description into this nowhere and studying it--and making notes--in cipher at that! It was an extravagant mystery. Excerpt from Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1899) History shows me one way, and one way only, in which a high state of civilization has been produced, namely, the struggle of race with race, and the survival of the physically and mentally fitter race. If you want to know whether the lower races of man can evolve a higher type, I fear the only course is to leave them to fight it out among themselves, and even then the struggle for existence between individual and individual, between tribe and tribe, may not be supported by that physical selection due to a particular climate on which probably so much of the Aryan's success depended. . . The struggle means suffering, intense suffering, while it is in progress; but that struggle and that suffering have been the stages by which the white man has reached his present stage of development, and they account for the fact that he no longer lives in caves and feeds on roots and nuts. This dependence of progress on the survival of the fitter race, terribly black as it may seem to some of you, gives the struggle for existence its redeeming features; it is the fiery crucible out of which comes the finer metal. You may hope for a time when the sword shall be turned into the plowshare, when American and German and English traders shall no longer compete in the markets of the world for their raw material and for their food supply, when the white man and the dark shall share the soil between them, and each till it as he lists. But, believe me, when that day comes mankind will no longer progress; there will be nothing to check the fertility of inferior stock; the relentless law of heredity will not be controlled and guided by natural selection. Man will stagnate; and unless he ceases to multiply, the catastrophe will come again; famine and pestilence, as we see them in the East, physical selection instead of the struggle of race against race, will do the work more relentlessly, and, to judge from India and China, far less efficiently than of old. . . There is a struggle of race against race and of nation against nation. In the early days of that struggle it was a blind, unconscious struggle of barbaric tribes. At the present day, in the case of the civilized white man, it has become more and more the conscious, carefully directed attempt of the nation to fit itself to a continuously changing environment. The nations has to foresee how and where the struggle will be carried on; the maintenance of national position is becoming more and more a conscious preparation for changing conditions, an insight into the needs of coming environments. We have to remember that man is subject to the universal law of inheritance, and that a dearth of capacity may arise if we recruit our society from the inferior and not the better stock. If any social opinions or class prejudices tamper with the fertility of the better stocks, then the national character will take but a few generations to be seriously modified. The pressure of population should always tend to push brains and physique into occupations where they are not a primary necessity, for in this way a reserve is formed for the times of national crisis. Such a reserve can always be formed by filling up with men of our own kith and kin the waste lands of the earth, even at the expense of an inferior race of inhabitants. . . . You will see that my view---and I think it may be called the scientific view of a nation--is that of an organized whole, kept up to a high pitch of internal efficiency by insuring that its numbers are substantially recruited from the better stocks, and kept up to a high pitch of internal efficiency by insuring that its numbers are substantially recruited from the better stocks, and kept up to a high pitch of external efficiency by contest, chiefly by way of war with inferior races, and with equal races by the struggle for trade-routes and for the sources of raw material and of food supply. This is the natural history view of mankind, and I do not think you can in its main features subvert it. Some of you may realize it, and then despair of life; you may decline to admit any glory in a world where the superior race must either eject the inferior, or, mixing with it, or even living alongside it, degenerate itself. What beauty can there be when the battle is to the stronger, and the weaker must suffer in the struggle of nations and in the struggle of individual men? You may say: Let us cease to struggle; let us leave the lands of the world to the races that cannot profit by them to the full; let us cease to compete in the markets of the world. Well, we could do it, if we were a small nation living on the produce of our own soil, and a soil so worthless that no other race envied it and sought to appropriate it. We should cease to advance; but then we should naturally give up progress as a good which comes through suffering. . . The man who tells us that he feels to all men alike, that he has no sense of kinship, that he has no patriotic sentiment, that he loves the Kaffir as he loves his brother, is probably deceiving himself. If he is not, then all we can say is that a nation of such men, or even a nation with a large minority of such men, will not stand for many generations; it cannot survive in the struggle of the nations, it cannot be a factor in the contest upon which human progress ultimately depends. The national spirit is not a thing to be ashamed of, as the educated man seems occasionally to hold. If that spirit be the mere excrescence of the music hall, or an ignorant assertion of superiority to the foreigner, it may be ridiculous, it may even be nationally dangerous; but if the national spirit takes the form of a strong feeling of the importance of organizing the nation as a whole, of making its social and economic conditions such that it is able to do its work in the world and meet its fellows without hesitation in the field and in the market, then it seems to me a wholly good spirit---indeed, one of the highest forms of social, that is, moral instinct. So far from our having too much of this spirit of patriotism, I doubt if we have anything like enough of it. We wait to improve the condition of some class of workers until they themselves cry out or even rebel against their economic condition. We do not better their state because we perceive its relation to the strength and stability of the nation as a whole. Too often it is done as the outcome of a blind class war. The coal owners, the miners, the manufacturers, the mill-hands, the landlords, the farmers, the agricultural laborers, struggle against each other, and, in doing so, against the nation at large, and our statesmen as a rule look on. That was the correct attitude from the standpoint of the old political economy. It is not the correct attitude from the standpoint of science; for science realizes that the nation is an organized whole, in continual struggle with its competitors. You cannot get a strong and effective nation if many of its stomachs are half fed and many of its brains untrained. We, as a nation, cannot survive in the struggle for existence if we allow class distinctions to permanently endow the brainless and to push them into posts of national responsibility. The true statesman has to limit the internal struggle of the community in order to make it stronger for the external struggle. We must reward ability, we must pay for brains, we must give larger advantage to physique; but we must not do this at a rate which renders the lot of the mediocre a wholly unhappy one. We must foster exceptional brains and physique for nation purposes; but, however useful prize cattle may be, they are not bred for their own sake, but as a step toward the improvement of the whole herd. Science is not a dogma; it has no infallible popes to pronounce authoritatively what its teaching is. I can only say how it seems to one individual scientific worker that the doctrine of evolution applies to the history of nations. My interpretation may be wrong, but of the true method I am sure: a community of men is as subject as a community of ants or as a herd of buffaloes to the laws which rule all organic nature. We cannot escape from them; it serves no purpose to protest at what some term their cruelty and their bloodthirstiness. Mankind as a whole, like the individual man, advances through pain and suffering only. The path of progress is strewn with the wreck of nations; traces are everywhere to be seen of the hecatombs of inferior races, and of victims who found not the narrow way to the greater perfection. Yet these dead peoples are, in very truth, the steppingstones on which mankind has arisen to the higher intellectual and deeper emotional life of today. Karl Pearson, National Life from the Standpoint of Science, 1900 1) From approximately 1880 until the outbreak of WORLD WAR I in 1914, the nation-states of Europe engaged in what scholars have termed the New Imperialism, which is essentially aggressive COLONIAL EXPANSIONISM into ASIA, AFRICA, and the SOUTH PACIFIC on an UNPRECEDENTED scale. Colonialism itself was nothing new, as Europe had a centuries-long history of establishing colonies, but again, among other differences, what impresses one here is the GLOBAL SCALE on which this was accomplished, particularly in AFRICA, along with the tremendous effects of this colonialism on INDIGENOUS POPULATIONS. The numbers are staggering—in the mid 1870’s, approximately 10% of Africa had been colonized and PARTITIONED by the Europeans; around the turn of the century this had increased to nearly 90%. 2) Explanations for this OUTBURST in colonialism range from the inevitable expansionism of CAPITALISM (Lenin: Imperialism—the Last Stage of Capitalism) as a consequence of the new-found wealth generated by the industrial revolution and its demands for new MARKETS, RAW MATERIALS, and low WAGES, to a strategy for DISTRACTING citizens from domestic policy FAILURES (i.e., social imperialism) and the FEAR that competitors would reach these areas earlier and CLOSE OFF potential markets and sources of investment and raw materials. In the case of FRANCE, strong arguments have likewise been made that it was seeking a sort of national VALIDATION, having in the last century experienced the revolution and then having lost a series of wars under the Bonaparte dynasty. GERMANY was now far too strong on continental Europe for the French to once again attempt expansionism, and so the logical solution for them was to look elsewhere for legitimization. 3) Perhaps Dr. David Livingston, the great figure of British imperialist colonization, put it best when he noted that Christianity, Commerce and Civilization were the main motives for Europe’s imperialistic activities; others put it more succinctly: God, Gold and Glory. “Superior” European culture, religion, and ideals would be spread worldwide, and would succeed because they represented the survival of the fittest (Herbert Spencer, NOT Darwin) from this very Eurocentric perspective that is much exemplified by the Karl Pearson reference included in your handout captions. 4) The 90% of African colonization represented not only the traditional MAJOR Powers (e.g., Britain in South Africa, Egypt, the Sudan and Rhodesia and France in French Equatorial Africa, French West Africa, Morocco, Algeria and Indochina) but MINOR powers (e.g., Belgium in the Congo, Portugal in Mozambique and Angola, Germany in Cameroon and Namibia, and Italy in Libya and Somalia) as well. This list is far from exhaustive: India, New Guinea, Singapore, and Indochina and China (including RUSSIA in Manchuria) were subjected to the colonialism of this NEW IMPERIALISM. 5) The issue then becomes why this is termed the NEW imperialism; that is, how specifically does it differ from the COLONIALISM that preceded it? Perhaps the most SALIENT difference was that the HOST populations were now SUBJUGATED in ways that were unlike the PAST; in addition to the availability of capital for investment, this was enabled by the relative TECHNOLOGICAL sophistication of Europe compared to these populations. Metal-hulled STEAMSHIPS reduced the time required to travel from LIVERPOOL to CAPETOWN from three MONTHS to three WEEKS and enabled fast, efficient travel UP RIVER into the deep parts of continents, a CABLE laid between South Africa and London in 1885 that provided almost IMMEDIATE communication, and QUININE helped control MALARIA so that the jungle could be penetrated to depths that were previously impossible because of this disease. 6) Further, WEAPONRY developed in sophistication, with early forms of the MACHINE GUN enabling explorers and settlers to impose their will on INDIGENOUS populations much more easily than was possible with only the sword and a single-shot rifle—in 1898 the British killed 20K SUDANESE in a single battle, and in southwest Africa the Germans killed over 60K HERRERO people in NAMIBIA between 1904 and 1908, winning the commander a MEDAL from William II. And so, Europeans were by no means any longer limited to settling COASTLINES, as they now possessed by the weaponry and transportation technology to exploit the resources of the interior and COERCE the indigenous peoples into helping them to do it and DESTROY them if they did not. 7) By 1885 it became obvious that the kind of expansionism currently occurring required a new set of ground rules, thus leading to a conference in BERLIN to provide just that so that the colonial powers could avoid WAR over these new territorial CLAIMS. And so, FIRST CLAIM to a region was given to that power which had already established SUBSTANTIVE colonies and trading posts on the COASTS. The VALIDITY of this claim was predicated upon a MILITARY PRESENCE and the existence of a CIVIL ADMINISTRATION, and so a country could not simply establish a small outpost and lay claim to both the COASTLINE and INTERIOR of a particular region. With such INSTITUTIONAL CONTROL thus established, the foundation for the EXPLOITATION of the indigenous populations was now solidly in place, since the goal was not to develop these colonies as entities in themselves but rather only insofar as they might serve the economic and social needs of the MOTHER STATE. 8) Such exploitation was not long in coming. For example, during the 1890’s very large areas of the FRENCH CONGO were placed under the control not of the government, but rather of PRIVATE rubber harvesting companies, thus leading to the HORRIFIC abuse and virtual ENSLAVEMENT of the local population for the purpose of serving these companies—ultimately due to the public OUTCRY the French Government was forced to intervene. The colony with the WORST reputation for exploitation was the BELGIAN CONGO, which had originally been viewed by LEOPOLD II of Belgium as his own PRIVATE game and nature preserve, but under significant INTERNATIONAL PRESSURE it finally became a FORMAL Belgian colony. The activities of Belgium in the Congo, the trip UP RIVER and the subsequent exploitation of the native population, is the subject of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, an excerpt from which served as the caption for this handout. 9) Very little thought was given to ETHNIC and SOCIAL considerations when colonies were established; as a result people who shared little in common other than the fact that they had been conquered by the Europeans found themselves lumped together in ways that would not have occurred without European colonial influence. Consequently, when DECOLONIZATION began subsequent to the end of WWII, the states that were created still reflected Europe’s POLITICAL INFLUENCE instead of African heritage, culture and history, thus enormously COMPLICATING the building of the African nation-states relative to these criteria. 10) European colonization was closely monitored by the so-called age of YELLOW JOURNALISM through which non-colonists remaining in Europe could follow virtually every movement made in these new territories— especially AFRICA—often in a competitive coloring in the map to see who at any one point possessed more territory—France, Belgium, England or Germany—and thus became a source of NATIONAL PRIDE, especially since virtually every European state involved in colonial ventures now had UNIVERSAL MALE SUFFRAGE. And so, not unexpectedly, the consequence of this Race for Africa was a sense of enormous TENSION between the major European powers, an outcome that had been foreseen by BISMARCK as early as the 1870’s. 11) In his traditional strategy of REALPOLITIK, Bismarck had therefore actually ENCOURAGED France to move into Africa, hoping that this move would bring France into conflict with ENGLAND. What likewise emerges from this environment is perhaps the earliest modern ARMS RACE, as the continental powers becomes CONVINCED that the key to the successful defense of both HOMELAND and COLONIES was in the form of a very powerful NAVY that could protect a country’s TRANS-GLOBAL economic interests. 12) Between 1859 and 1869, the FRENCH had built the SUEZ CANAL which offered quick and easy access from the MEDITERNEAN SEA into the INDIAN OCEAN and thus, for England, easy access to the jewel in the crown of the British Empire. Sensing and opportunity to protect its interests especially as they grew in INDIA, the British purchased nearly 50% of the stock in the company in 1875, and placed the rule of Egypt under British protection in 1882 because it feared disruptive INTERNAL Egyptian politics, thus making essentially a British PROTECTORATE out of Egypt. 13) The CAPE to CAIRO railway project was backed by the British statesman CECIL RHODES who envisioned a strong North-South axis of British power traversing the African continent; this conflicted with the corresponding FRENCH agenda to move from WEST to EAST cross the continent; during several instances the result was very nearly WAR. Elsewhere, in 1904-1905 the RUSSO-JAPANESE War resulted in the first DEFEAT of a major European power by an ASIATIC power. Japan itself had IMPERIALIST ambition, and within this context this war involved disputes over territories in MANCHURIA and KOREA. 14) In 1896, the first defeat of a European power by an indigenous African people occurred when the ITALIANS were defeated by around 80,000 exceptionally wellequipped ETHIOPIANS who subsequently CASTRATED the Italian prisoners of war, and resulted in the Italian determination to crush the Ethiopians during the 1930’s. 15) And so, by the late 19th century, the nation-states, colonialism and general milieu were all present in a mixture that would insure a turbulent 20th century. Consider a 1934 treatment of this period from the Cambridge Modern History (volume 12 pgs. 666-671) involving areas besides Africa: In another part of the world, new ground has been broken. The many archipelagos of the Pacific, discovered by Spanish and Portuguese navigators in the 16th century, remained, with the exception of the Philippines, neglected, until they were rediscovered, in the latter part of the 18th century, by rival French and English explorers who opened the Pacific once more to human enterprise. But, though Australia and New Zealand were colonized, the annexation of small groups of islands offered no advantage, and the Pacific Islanders continued to live their life in peace or war as was their wont. In time, however, missionaries penetrated into Hawaii, Fiji, the New Hebrides, and elsewhere; and, when Australia began the culture of cotton and sugar, labor traders visited the Loyalties, the New Hebrides, the Solomons, and other groups, to kidnap or hire the natives for work on the plantations. In 1864, France planted a penal settlement in New Caledonia, which she annexed in 1853. German traders established themselves in Samoa, Fiji, the Caroline and Marshall Groups, as well as in some of the larger islands off the coast of New Guinea. Thus, in various ways, the Pacific groups felt the touch of European life, and, becoming the scene of its competing energies, were partitioned and annexed. To this issue England led the way. In 1874, influenced by the abuses connected with labor traffic, which required regulation and oversight, the commercial interests of Sydney, and the fear lest some other Power might anticipate her, she annexed the Fiji Islands, whose governor was in 1875 created High Commissioner of the Western Pacific, with jurisdiction over British subjects in those parts. In the ensuing thirty years, the Pacific was mapped out into spheres of influence and the smallest islands passed under the protection of some foreign power. In 1878, the United States a coaling and naval station at Pago Pago in the Samoas. Both English and French were interested in the New Hebrides, islands near both New Caledonia and Queensland; but for a time they were content with a policy of mutual exclusion, which in 1887 gave way to joint control. The French, meanwhile, turned to Polynesia, and annexed the Windward Islands of the Society group, to the intense irritation of New Zealand. Australia was more concerned as to the intentions of Germany in New Guinea; and, determined to forestall her, the Prime Minister of Queensland in 1883 annexed the non-Dutch part of the island to the British Empire. The mother country repudiated the action. But Australian instinct had divined the truth, and in 1884 Germany annexed parts of northern New Guinea, Great Britain thereupon annexing the remainder. In 1885 and 1886, the three powers with the chief interests in the Pacific came to a general agreement as to their respective spheres of influence. Germany mapped out a great area in Micronesia and western Melanesia in proximity to the historic possessions of the Dutch, including the Carolines, Marshalls, part of the Solomon group, and Northern New Guinea. The French claimed a sphere of influence in Melanesia, of which New Caledonia was the center, and another in Polynesia, with the Society Islands at its center…Such in its brief outline is the story of recent colonization. The main course of the work accomplished has been directed by young communities controlling their own life. Yet, from any point of view, the whole development must be regarded as a marvelous manifestation of European energy. Europe has supplied the stream of immigrants and capital without which the new lands could not have achieved their rapid progress, and it has continued, in the words of Adam Smith, to breed and form men capable of laying the foundations of new States. The explorers, traders, and governors of recent times have paralleled the feats of their predecessors. It is possible that their efforts will not bear equal fruit in the birth of European societies in other continents, since many of the lands occupied have proved unsuitable in climate to become the homes of white races. In some new countries, moreover, the period of beginnings and experiment is not yet past, and it remains for the future to declare the form which their colonization will take. But, if in certain directions the efforts of the colony builder have been yielding a diminishing return, the substantial result remains, that almost all the vacant lands and weaker races of the world have passed under the control of Europe and been drawn into its economic and political life. The transformation in many cases of a commercial connection into political sovereignty, and the consequent assumption of governing responsibilities over millions of people, constitute a change fraught with so great significance that its influence will only slowly be worked out. The great power and prestige of Germany, and the exertions which she has put forth to increase her commerce and influence in distant parts of the world, give to her colonial experiments and policy a singular importance. Her expanding population and industries have compelled her to seek outlets for her trade and people in oversea possessions. But her struggle for unity delayed so long her entry into the colonial field that she has failed to acquire lands where white communities can be formed, and her recent acquisitions have been for the most part trading and plantation settlements whence raw materials to feed her industries can be supplied. Want of experience in dealing with primitive peoples has involved her in frequent and expensive wars; but, with conspicuous energy and system, she has applied herself to master the problems of colonization and to develop the territories she has occupied. Her great strength, power of organization, and a willingness to make sacrifices to achieve her purposes, mark her determined entry into the colonial field as one of the most pregnant developments of recent years. Of less importance, but of great historical interest, has been the virtual withdrawal of one of the oldest colonizing powers. The enduring work of Spain was done in the earlier centuries of modern colonial history. After the loss of her great empire her energies slackened, though her name and power lingered on in the West Indies and the Philippine archipelago. Here also, towards the end of the 19th century, she surrendered her place to an Anglo-Saxon power of unresting activity and bold ideals. It is now possible to look back upon her work without prejudice. The first of European peoples to plant colonies in distant lands, she created and maintained her own policy in government and economics. Her exclusive principles never commended themselves altogether to other powers, and her system was not copied; but it will be admitted that she knew how to plant her civilization wherever she held sway, and to secure her authority even when her strength and maritime greatness declined. Her dominion lasted long and died hard; today, in the two continents where it existed, several young nations own her their parent. The last word may be of the British Empire. The experience of the past has not been wasted on the mother country; and, with more fortune and greater wisdom, she has been steering through the difficult waters in which she formerly made shipwreck. Her colonial policy has been inspired by an understanding and a wise recognition of facts. Settlers in new countries form societies; such societies, as their strength grows, desire the control of their own life; common interests draw connationality. Perceiving the course of this development, the mother country has continually readjusted the ties that bound her to her colonies, so that they might be appropriate to the stage of growth which each colony had reached. Whenever possible, she has conceded to them the full control of their own affairs; and she has encouraged contiguous colonies to unite, so that in dimensions, resources, population and economic strength, the indispensable material foundations of a self-governing state could be formed. Thus, an issue which once burst upon her with the suddenness of accident and disaster, rudely breaking the thread of her work and transforming its political significance, has since been sought and is in course of achievement, though in a manner that gives a greater freedom to natural processes of growth and saves the continuity and completeness of the work of the race, at once creating nations and retaining them in the unity of a great state. Slowly the British Empire is shaping itself into a league of Anglo-Saxon peoples, holding under its sway vast tropical dependencies as well as many small communities of mixed race. Strong bonds of common loyalty, race, and history, as well as the need of cooperation for defense, unite the white peoples. But the course of progress has carried the empire to an unfamiliar point in political development. Loose and elastic in its structure, it may well take a new shape under the influence of external pressure, political and economic.