Bricknell v TAC Pacific Pty Ltd [2011]

advertisement

![Bricknell v TAC Pacific Pty Ltd [2011]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/008970501_1-8d930bca7d1fcb71bc38c1e735199e70-768x994.png)

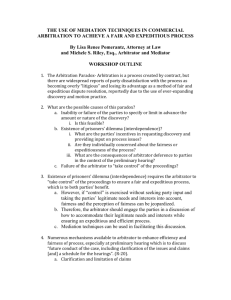

Issue 10: October 2011 On Appeal Welcome to the 10th issue of ‘On Appeal’ for 2011. Issue 10 – October 2011 includes a summary of the September 2011 decisions. These summaries are prepared by the Presidential Unit and are designed to provide a brief overview of, and introduction to, the most recent Presidential and Court of Appeal decisions. They are not intended to be a substitute for reading the decisions in full, nor are they a substitute for a decision maker’s independent research. Please note that the following abbreviations are used throughout these summaries: ADP AMS Commission DP MAC Reply 1987 Act 1998 Act 2003 Regulation 2010 Regulation 2010 Rules 2011 Rules Acting Deputy President Approved Medical Specialist Workers Compensation Commission Deputy President Medical Assessment Certificate Reply to Application to Resolve a Dispute Workers Compensation Act 1987 Workplace Injury Management and Workers Compensation Act 1998 Workers Compensation Regulation 2003 Workers Compensation Regulation 2010 Workers Compensation Commission Rules 2010 Workers Compensation Commission Rules 2011 Level 21 1 Oxford Street Darlinghurst NSW 2010 PO Box 594 Darlinghurst 1300 Australia Ph 1300 368018 TTY 02 9261 3334 www.wcc.nsw.gov.au 1 Table of Contents Court of Appeal Ayoub v AMP Bank Limited [2011] NSWCA 263 ............................................................... 3 WORKERS COMPENSATION - appeal - appeal against finding of the Acting Deputy President appeal limited to party being aggrieved by a decision of the Presidential member in point of law denial of procedural fairness - matter proceeded on the papers - failure to consider oral hearing when matters of credit to be decided - whether parties acquiesced in review on the papers whether failure of Acting Deputy President to take into account internal retrenchment policies of appellant constituted an error of law - no error shown - no denial of procedural fairness ............. 3 McCarthy v Patrick Stevedores No 1 Pty Ltd [2011] NSWCA 311 .................................... 7 Workers compensation – appeal against decision of Deputy President – limited to decisions in point of law – whether there was a misapplication of s 40 of the 1987 Act – whether there was evidence to support the Deputy President’s finding – whether there was a failure to give adequate reasons – whether there was a denial of procedural fairness in making a determination on the papers – no error in point of law .......................................................................................... 7 Presidential decisions Awick v Formcorp Pty Ltd (No 2) [2011] NSWWCCPD 50 .............................................. 10 Estoppel; nature of issues in dispute in earlier proceedings between the same parties; whether issue estoppel arose from earlier determination; whether worker had received a primary psychological injury or secondary psychological injury; s 65A of the Workers Compensation Act 1987 .............................................................................................................................................. 10 Bricknell v TAC Pacific Pty Ltd [2011] NSWWCCPD 53 ................................................. 12 Injury; whether the worker was bitten by an insect in the course of employment; application to rely on fresh evidence or additional evidence on appeal; s 352(6) of the Workplace Injury Management and Workers Compensation Act 1998; failure to prepare objective chronology of the principle events....................................................................................................................... 12 Nguyen v WorkCover Authority of New South Wales [2011] NSWWCCPD 55 .............. 14 Employment; identity of worker’s employer; whether employed by an individual or a partnership; whether a partnership existed; credit findings; application of principles in Fox v Percy [2003] HCA 22; 214 CLR 118 .................................................................................................................. 14 North Coast Area Health Service v Felstead [2011] NSWWCCPD 51 ............................ 17 Personal injury under s 10 of the Workers Compensation Act 1987; disease injury; personal injury; journey incident; failure to give adequate reasons ............................................................ 17 Jetstar Airways Pty Ltd v Canterbury [2011] NSWWCCPD 54 ....................................... 22 Psychological injury; whole or predominant cause of injury; reasonable action taken with respect to discipline; s 11A of the 1987 Act .............................................................................................. 22 East Coast Timber Products Pty Ltd v Hancock (No2) [2011] NSWWCCPD 48 ............ 24 Arbitrator erred in failing to give adequate reasons for his decision; determined on remitter from the Court of Appeal....................................................................................................................... 24 Koutsioukis and Koutsioukis t/as Taste of Europe Bakery v Bouza [2011] NSWWCCPD 52 ...................................................................................................... 27 Costs where appellants filed Election to Discontinue Proceedings; s 341 Workplace Injury Management and Workers Compensation Act 1998 ................................................................... 27 2 Ayoub v AMP Bank Limited [2011] NSWCA 263 WORKERS COMPENSATION - appeal - appeal against finding of the Acting Deputy President - appeal limited to party being aggrieved by a decision of the Presidential member in point of law - denial of procedural fairness - matter proceeded on the papers - failure to consider oral hearing when matters of credit to be decided - whether parties acquiesced in review on the papers - whether failure of Acting Deputy President to take into account internal retrenchment policies of appellant constituted an error of law - no error shown - no denial of procedural fairness Basten JA, Whealy JA and Sackville AJA 7 September 2011 Facts: Ms Ayoub was employed by AMP Bank Limited as one of three Product Managers. In 2007, her work situation began to deteriorate. Her manager was replaced with a new manager, Mr Slocombe, who she had worked with at an earlier time and did not like. She perceived that he was critical of some aspects of her work. In her performance appraisal, her performance was graded as “satisfactory”. She ventilated her dissatisfaction with this grade at a meeting in March 2007 with Mr Slocombe and AMP’s Managing Director, Mr White. She later complained that she was very distressed by the events that occurred at that meeting. Mr White maintained that “the tone of the meeting was as friendly as I was able to make it”. At that meeting she was informed by Mr White that “other people” had complained to him about the inappropriateness of her dress and her behaviour on occasions at meetings. From March to November 2007, she perceived that she was being bullied and harassed by staff and treated unfairly and belittled by Mr Slocombe due to her race and gender. In 2007, it was decided that a restructure of the business was necessary to make it more efficient and effective. Ms Ayoub was unaware that there had been discussions at the executive level about the prospect of having only two Product Managers. Ms Ayoub’s position was made redundant on 15 November 2007. AMP tried, unsuccessfully, to redeploy her within its structure and it made counselling available to Ms Ayoub. That night she sent an email to Mr White complaining about the way she was treated at the performance appraisal meeting on 14 March 2007. She then lodged a notification of injury which described injury as “anxiety state/depression” and asserted that her employment was a substantial contributing factor. Allianz denied liability and identified the following issues (at [12]): (a) there was no evidence to confirm Ms Ayoub’s allegations of being subjected, by her managers, to ongoing harassment, bullying and intimidation; (b) according to Dr Ong, Ms Ayoub's general practitioner, she had recovered from any distress caused by the “satisfactory” performance rating; (c) Dr Ong opined that the distress suffered by Ms Ayoub as a result of her father’s death in September 2007 had abated; (d) certificates issued by Dr Ong noted that the events at work on 15 November 2007 caused anxiety and depression; 3 (e) Ms Gurton, psychologist, opined that the adjustment disorder suffered by Ms Ayoub was as a result of the redundancy; (f) there was no evidence that AMP acted unreasonably in relation to the redundancy; (g) AMP followed its policy in relation to the restructuring; (h) a number of staff were made redundant following the restructure of AMP; (i) counselling was made available, and (j) there was minimal medical evidence in support of the alleged injury, incapacity and need for treatment. In proceedings commenced in the Commission, Ms Ayoub sought weekly benefits from 15 November 2007, medical expenses and lump sum compensation. The Arbitrator found in Ms Ayoub’s favour after being impressed with her oral evidence in cross-examination and accepting her as a credible witness. He found that (at [19] – [25]): (a) she received a personal injury in the form of a psychological injury at the meeting on 15 November 2007; (b) the injury, being a major depressive disorder, qualified as a “personal injury”; (c) the injury arose out of or in the course of her employment; (d) the injury was sustained because she had been called to a meeting without prior consultation to inform her of her retrenchment; (e) employment was a substantial contributing factor to her psychological injury, and (f) in relation to the allegations of discrimination, the Arbitrator determined that a finding was not necessary as other proceedings had been commenced in courts of different jurisdictions and those courts were in a better position to determine those matters. AMP appealed the Arbitrator’s determination. AMP accepted that Ms Ayoub had sustained a psychological injury but challenged the finding that its actions in relation to the appraisal of her performance, and in relation to retrenchment, were unreasonable [29] – [30]. AMP submitted that there was “uncontested evidence” that the employer was obliged, for proper reasons, to diminish its staff [31]. The Arbitrator’s decision was revoked and an award entered for AMP (AMP Bank Ltd v Ayoub [2010] NSWWCCPD 37). Moore ADP found: 1. she had sufficient information to proceed with the appeal ‘on the papers’ [39]; 2. there was no other evidence (beyond Ms Ayoub’s evidence) in support of her allegations of discrimination. A witness who was described as her friend and colleague had not supported her allegations of sexual harassment, racial discrimination or bullying and described Ms Ayoub as having “issues with her perception of events” [43]. There were also other “conflicting statements” [44]. There was an absence of complaint between 26 March and November 2007 and Dr Ong and Ms Gunton did not refer to her being distressed over allegations of discrimination or harassment [43]; 3. that AMP’s actions in relation to the performance appraisal and the retrenchment were reasonable [45]; 4. there was “nothing to suggest that either the steps taken to appraise Ms Ayoub’s performance, or the manner in which the results were communicated to her was in any way unreasonable” [46] – [47]; 5. there were four matters, as discussed in Manly Pacific International Hotel Pty Ltd v Doyle (1999) 19 NSWCCR 181, that should be considered in determining whether a retrenchment process had been unreasonable (at [48]): i. ii. the general circumstances of the employment relationship between the employer and employee; the suddenness or otherwise of the “fall of the axe”; 4 iii. iv. the period of notice given, and the existence of counselling and other services provided at the time of retrenchment, including consideration as to alternative employment. Ms Ayoub appealed to the Court of Appeal and the issues for determination were (at [51]): a) whether Moore ADP erred by denying Ms Ayoub procedural fairness by failing to notify her that it was proposed to make a credit finding against her; b) whether Moore ADP considered whether she had sufficient information to proceed to a final determination ‘on the papers’ especially having regard to the decision to reconsider the credit findings of the Arbitrator; c) if Moore ADP did give consideration to the form of the hearing, whether it was reasonably open to her to be satisfied that she had sufficient information to proceed ‘on the papers’, and d) whether Moore ADP erred in failing to take into account AMP’s industrial policies and generally accepted standards of conduct in the workplace relating to redundancies. Held: Appeal dismissed with costs (Basten JA, Whealy JA and Sackville AJA agreeing) Procedural fairness 1. Procedural fairness must be afforded to parties in the hearing of a review under s 354 of the 1998 Act (see the decision of Basten JA in State Transit Authority of New South Wales v Chemler [2007] NSWCA 249; (2007) 5 DDCR 28 at [65]) [54]. 2. In the Notice of Opposition to the appeal against the decision of the Arbitrator, Ms Ayoub invited Moore ADP to make an assessment of those issues which had not been determined by the Arbitrator, that is, in relation to the discrimination issue [55]. The issue of the existence or otherwise of the incidents relating to the discrimination complaints had been raised by Ms Ayoub for decision by the Arbitrator and, for it to be resolved, there had to be a finding, a resolution of the conflicting statements of Ms Ayoub on the one hand, and all the other witnesses on the other [57]. 3. Moore ADP did not use the adverse credit findings she had made on the discrimination issue either unfairly or at all when she came to consider the issue of reasonableness in relation to the performance appraisal and retrenchment process [58]. 4. The parties agreed to a review of the decision of the Arbitrator ‘on the papers’. They were aware that there were disparities between the evidence of the witnesses. It was readily foreseeable that Moore ADP would seek to resolve those conflicts in the course of the review. In those circumstances, the request for review "on the papers" must have involved a conscious waiver of the entitlement to seek an oral hearing before Moore ADP. Unless Moore ADP adopted an approach which was not reasonably foreseeable on the material before her, the possibility that there could be a denial of procedural fairness by adopting the approach proposed by the parties was remote and did not occur in this case [64]. On the papers 5. Ms Ayoub argued that it must have become apparent during Moore ADP's deliberations that the resolution of the dispute required that an opportunity be afforded to Ms Ayoub to address the discrimination issue matters and, in particular, her credit in relation to those matters. Reference was made to Hancock v East Coast Timber 5 Products Pty Limited [2011] NSWCA 11 (Hancock) per Beazley JA at [96] and Tobias JA with whom Giles JA agreed at [120] - [122] in support of this submission [66]. 6. Hancock was distinguished on the basis that in Hancock a fundamental and central issue relating to causation of the plaintiff’s injury arose. The discrimination issue in this matter was one that Ms Ayoub asked to be addressed (while maintaining that the appeal could be determined ‘on the papers’) and once it was dismissed, it was an issue that had no bearing on the reasonableness of the employer’s actions in respect of the performance appraisal or the redundancy [68]. 7. Ms Ayoub said that the restructure was “bogus” and was just a means to carry out a predetermined decision to get rid of her. She pointed to three documents in support of this submission, in particular, a “create retrenchment” quote email request dated 11 September 2007 which she said should have alerted Moore ADP to the fact that AMP had determined to retrench her as far back as 11 September 2007 [69] – [70]. Although Moore ADP had not specifically mentioned that document, it was open to her to find that the redundancy and the process surrounding it was genuine, given the abundance of other documents and statements before her [72] – [73]. AMP’s redundancy policy 8. It was submitted that Moore ADP overlooked AMP’s own policy document on retrenchment and re-deployment when she came to the conclusion that the retrenchment process was reasonable [75]. 9. The absence of notice of retrenchment may, in a particular case, be unreasonable, but that would not always be the situation. Moore ADP determined that Ms Ayoub's position was not such that she ought to have been consulted over the issue of staff reduction. AMP’s decision to inform Ms Ayoub about her retrenchment on 15 November 2007 was not unreasonable. It was the retrenchment itself rather than the lack of notice of it that was causative of Ms Ayoub’s decompensation. The various steps taken by AMP to “cushion the impact of the retrenchment” represented a “reasonable approach” [77]. 10. AMP’s policy requirement to tell an employee about a proposed redundancy as soon as practicable did not prescribe a precise course of conduct, as the circumstances of a particular case would dictate what was required [78]. 6 McCarthy v Patrick Stevedores No 1 Pty Ltd [2011] NSWCA 311 Workers compensation – appeal against decision of Deputy President – limited to decisions in point of law – whether there was a misapplication of s 40 of the 1987 Act – whether there was evidence to support the Deputy President’s finding – whether there was a failure to give adequate reasons – whether there was a denial of procedural fairness in making a determination on the papers – no error in point of law Basten JA, Meagher JA and Handley AJA 27 September 2011 Facts: Mr McCarthy commenced work with the employer in 1982. On 29 August 1998, he fell onto his buttocks while attempting to sit on a swivel chair. He injured his back, right leg, left leg and left hip. There was no dispute as to the fact of his injury. In 2002 he claimed weekly compensation from 14 September to 27 November 1998 and for 9 February 1999. That claim was settled in November 2002. He later claimed lump sum compensation in respect of his injury. That claim was settled in March 2005. In August 2009, Mr McCarthy claimed weekly compensation for partial incapacity for the period from 1 July 1999 pursuant to s 40 of the 1987 Act. Mr McCarthy claimed that before the injury he was employed as an allocations officer performing clerical duties and duties which required walking and stair climbing, and that as a result of the injury he was downgraded to the position of a receiving and delivery clerk. The evidence before the Arbitrator included two statements of Mr McCarthy (16 October 2004 and 11 November 2009), medical reports and eight statements made in January or February 2010 from persons who worked with Mr McCarthy in or about 1998. The Arbitrator made an award for the respondent as Mr McCarthy had failed to establish the threshold proof of his pre-injury duties, his duties post injury, and the issues going to proof of economic loss. An appeal to a Presidential member was unsuccessful on the issue of a change to his duties as a result of the effects of his injury (McCarthy v Patrick Stevedores No 1 Pty Ltd [2010] NSWWCCPD 96). Held: Appeal dismissed with costs Meagher JA (Handley AJA agreeing) Misapplication of s 40 of the 1987 Act 1. The Deputy President concluded that Mr McCarthy had failed to establish that he had suffered any economic loss as a result of the injury. The Deputy President relied principally on Mr McCarthy’s evidence in his 2004 statement, that at the time of his injury, he carried out the duties of a receiving and delivery clerk and that this did not change as a result of the injury. Therefore, he was not satisfied that the amount which Mr McCarthy would probably have been earning, on the assumption that he was an uninjured worker still engaged in the same employment, would have been other than what he was able to earn as a receiving and delivery clerk. That finding disclosed no error. [38]-[40] 7 No evidence for finding 2. This ground was not pressed in the written or oral argument. There was evidence before the Deputy President to support his finding that before his injury, the appellant’s duties changed from an allocations officer to a receiving and delivery clerk. That evidence included Mr McCarthy’s 2004 statement as well as medical evidence which were inconsistent with the claim that he was unable to work as an allocations officer because of his injury. [41] Failure to give adequate reasons 3. The appellant’s written submissions did not identify any respect in which the Deputy President’s reasons did not reveal the ground for a crucial finding of fact. The appellant’s arguments were that the Deputy President’s conclusion was against the weight of the evidence or did not take sufficient account of other contrary evidence. Those were arguments that there was an error of fact. The Deputy President identified the primary ground for his conclusion being a preference for Mr McCarthy’s 2004 statement and the histories in the medical reports, over the evidence of lay witnesses given 11 years after the event. That was sufficient explanation of the ground for his crucial finding of fact and did not constitute an error of law. [42] Dealing with the matter “on the papers” 4. The appellant submitted there was a denial of procedural fairness in dealing with the evidence of the lay witnesses. He argued that the inconsistencies should not have been resolved between those statements and the appellant’s evidence without giving the appellant the opportunity to address on that question and whether there was any need for those witnesses to be cross-examined. This submission was rejected on appeal. [43] 5. There was conflicting evidence on the factual issue as to the appellant’s position and duties at the time of his injury. It included Mr McCarthy’s evidence in his 2004 and 2009 statements as well as the lay witness statements and medical evidence. Before the Arbitrator, the respondent argued that Mr McCarthy’s evidence in his 2004 statement and the medical evidence should be preferred to the recollection of the lay witnesses 10 years after the event. That submission was made notwithstanding that none of that evidence had been tested by cross-examination. [45] 6. Therefore when he lodged his appeal against the Arbitrator’s decision and agreed the appeal be decided solely on the papers, he was on notice that these inconsistencies and conflicts in the evidence would need to be addressed and resolved. The appellant therefore had a reasonable opportunity to address the question of how the Deputy President should regard the untested evidence of the lay witnesses. [46] 7. The Deputy President considered whether it was necessary to cross-examine the lay witnesses. He was satisfied that it was not necessary to test the reliability of their evidence on the basis it was given 11 years after the event. His proceeding on that basis did not involve any error in applying s 354 of the 1998 Act, in particular sub-s 354(6) which enables the exercise of functions without a formal hearing if “the Commission is satisfied that sufficient information has been supplied to it in connection with the proceedings”. [47] 8 8. The appellant relied on Hancock v East Coast Timber Products Pty Ltd [2011] NSWCA 11 (Hancock). The circumstances in this case were different from those in Hancock where there was an issue as to whether the worker’s incapacity was caused by the work incident. The evidence relied upon by the worker included reports by his treating orthopaedic surgeon. The President of the Commission in Hancock held that the worker had failed to discharge the onus of proving that his incapacity resulted from the work incident. That conclusion was based substantially upon the rejection of evidence of the orthopaedic surgeon because the facts upon which his opinion was based did not provide a proper foundation for it (Makita (Australia) Pty Ltd v Sprowles [2001] NSWCA 305; 52 NSWLR 75). That question had not been raised either before the Arbitrator or the President. On appeal to the Court of Appeal, it was held that the appellant worker had been denied procedural fairness (Hancock). [48] Basten JA 9. There is no obligation to accord procedural fairness to a witness: nor will a judgment be set aside on the basis of a failure to take such a step. The impropriety in issue in Hancock was that of a party in making submissions attacking the integrity of a witness in circumstances where it had not sought to cross-examine. [8] 9 Awick v Formcorp Pty Ltd (No 2) [2011] NSWWCCPD 50 Estoppel; nature of issues in dispute in earlier proceedings between the same parties; whether issue estoppel arose from earlier determination; whether worker had received a primary psychological injury or secondary psychological injury; s 65A of the Workers Compensation Act 1987 Roche DP 8 September 2011 Facts: The main issue in this appeal was whether an issue estoppel arose from an earlier decision by an Arbitrator in proceedings between the same parties where, in later proceedings, the worker sought different relief arising out of the same accident. Mr Awick worked as a labourer for Formcorp Pty Ltd. On 30 June 2007, he was struck on the head by falling scaffolding on a building site. In a decision dated 18 February 2009, Arbitrator Conley found that Mr Awick injured his head and neck in the incident on 30 June 2007 and accepted that there was “some level of anxiety and depression as a result of the injury” which contributed to his incapacity. She made an award in his favour under s 40 of the 1987 Act. In further proceedings in 2010, Mr Awick was unsuccessful in seeking an increase in his weekly compensation due to an alleged deterioration in his psychological condition. On 7 December 2010 he sought lump sum compensation in respect of a primary psychological injury received in the incident on 30 June 2007. Formcorp disputed this and argued that Arbitrator Conley’s decision determined that the psychological injury was secondary to his physical injuries and that that decision created an issue estoppel. Mr Awick argued that Formcorp was estopped from denying that he had received a primary psychological injury. Arbitrator Edwards determined that no issue estoppel arose from Arbitrator Conley’s decision as she did not determine the issue of whether Mr Awick suffered a primary or secondary psychological injury. He also determined that Mr Awick suffered a secondary psychological injury and was not entitled to lump sum compensation for that condition: s 65A(1) of the 1987 Act. Mr Awick appealed and argued that Arbitrator Edwards erred in failing to find that Arbitrator Conley’s decision created an issue estoppel, in accepting the evidence from Drs Roldan, Champion and Moore whose opinions, had been, by implication, rejected by Arbitrator Conley. Held: Arbitrator’s decision confirmed 1. A primary psychological injury and a physical injury can result from the one incident (Romanous Constuctions Pty Ltd v Arsenovic [2009] NSWWCCPD 82). The question was whether Arbitrator Conley made such a finding in the first proceedings to create an estoppel on that issue in the later proceedings [28]. 10 2. It was clear from Arbitrator Conley’s reasons that no question arose in the proceedings before her as to whether Mr Awick had received a primary or secondary psychological injury. Therefore, she did not consider that question or make a determination on it [29]. Nor did she say whether the worker’s psychological condition had resulted from the physical effects of the neck injury or from the traumatic circumstances of the accident [33]. 3. Arbitrator Conley’s acceptance of the submission that Mr Awick had developed a psychological condition as a result of the incident did not address the issue which arose in the proceedings before Arbitrator Edwards, namely, whether, within the terms of s 65A of the 1987 Act, Mr Awick suffered a primary psychological injury or a secondary psychological injury [37]. 4. In a statement approved by the High Court in Kuligowski v MetroBus [2004] HCA 34; 220 CLR 363 (at [21]), Lord Guest held in Carl Zeiss Stiftung v Rayner & Keeler Ltd (No 2) [1967] 1 AC 853 (at 935) that, for an issue estoppel to arise, three conditions must be satisfied: “(1) that the same question has been decided; (2) that the judicial decision which is said to create the estoppel was final; and, (3) that the parties to the judicial decision or their privies were the same persons as the parties to the proceedings in which the estoppel is raised or their privies.” [38] 5. Mr Awick’s argument fell at the first hurdle. Arbitrator Conley did not decide whether his psychological condition was a primary psychological injury or a secondary psychological injury. That issue was not pleaded or argued before her. 6. The argument that Arbitrator Edwards erred in accepting Formcorp’s medical evidence because it had already been rejected by Arbitrator Conley was dependent on the acceptance of the estoppel argument [40]. The estoppel argument was rejected. 7. Arbitrator Conley found that Mr Awick had “some level of anxiety and depression as a result of the injury” but did not accept that Mr Awick suffered a post-traumatic stress disorder as a result of the accident. This finding was consistent with the evidence from Drs Roldan and Champion that Mr Awick did not have post-traumatic stress disorder and that he embellished his presentation [41]. 8. These doctors were critical of a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder by Mr Awick’s treating psychologist but Dr Roldan could not entirely discount that Mr Awick may have had some genuine reactive psychological symptoms [42]. It was open to Arbitrator Edwards to accept this opinion. 9. It was open to Arbitrator Edwards to accept Dr Moore’s evidence, which was consistent with Arbitrator Conley’s decision. Dr Moore diagnosed Mr Awick with a chronic pain disorder with predominant psychological symptoms related to his chronic adjustment disorder with predominant depression [44]. 10. The finding that Mr Awick suffered a secondary psychological injury was open to Arbitrator Edwards and disclosed no error. 11. The appeal was completely without merit. All claims for permanent impairment in respect of an injury should be made at the same time: s 263 of the 1998 Act. It was unacceptable that there were multiple proceedings arising out of the same incident [49]. 11 Bricknell v TAC Pacific Pty Ltd [2011] NSWWCCPD 53 Injury; whether the worker was bitten by an insect in the course of employment; application to rely on fresh evidence or additional evidence on appeal; s 352(6) of the Workplace Injury Management and Workers Compensation Act 1998; failure to prepare objective chronology of the principle events Roche DP 21 September 2011 Facts: In April 2001, the appellant, Mr Bricknell, experienced weight loss, rashes, myalgia and other symptoms consistent with renal failure. He was subsequently diagnosed with HenochSchönlein purpura, a form of allergic purpura with erythema. He alleged that his condition was caused by a spider bite on 9 April 2001 while he was at a work conference in Sydney. He noticed “big red welt marks around” his right ankle. He showed his ankle to his supervisor, Mr Keller, who advised him to leave the conference. Mr Bricknell claimed lump sum compensation in the sum of $28,000 in respect of a 20 per cent loss of use of each leg at and below the knee under the Table of Maims, plus compensation for pain and suffering in the sum of $40,000. TAC Pacific disputed liability on the ground that Mr Bricknell did not receive an injury on 9 April 2001. The Arbitrator entered an award for TAC Pacific as he found that Mr Bricknell had not established that he suffered injury by insect bite at work. On appeal, it was submitted that the Arbitrator erred in making that finding. Mr Bricknell sought to tender “new evidence” in the form of a statement from Mr Keller which confirmed that he “noticed red welt marks around the outside of [Mr Bricknell’s] ankle” and that “he also complained that his ankle was stinging” [40]. He submitted that the evidence was in contrast to the initial onset of Henoch-Schönlein purpura described by Dr Millar as presenting in most cases “as red spots spread over various parts of the body in the form of purpura”. The marks were not “spread over various parts of the body” and the rash did not appear until 16 days later. It was submitted that Mr Keller’s statement corroborated evidence of the “stinging” bite and confirmed that an event occurred to trigger the widespread rash [41(a)-(g)]. Mr Bricknell submitted that there was adequate evidence to support an inference that he was bitten by an insect at work causing “red welt marks” and “stinging” on 9 April 2001 and the widespread rash that appeared on 25 April 2001 [43]. Held: Arbitrator’s decision confirmed 1. The application to rely on “fresh evidence” did not address the terms of s 352(6). There was no evidence that Mr Keller’s statement could not reasonably have been obtained before the arbitration [47]. Mr Keller’s evidence did not add anything of relevance to the evidence that was before the Arbitrator and therefore there was no injustice in refusing the application to rely on his evidence on appeal [49]. 2. Dr Millar said that whether Mr Bricknell had a bite from an insect or purely the onset of Henoch-Schönlein purpura was “uncertain and would need someone to have seen the rash at the time and to have documented it to determine precisely whether he had or had not a bite from an insect” [51]. Mr Keller’s evidence, even if it was admitted on appeal, did not provide the kind of “documented” evidence referred to by Dr Millar [53]. 12 3. The inference that an insect bit Mr Bricknell on 9 April 2001 and caused his problems was not the only inference open on the evidence. Mr Bricknell’s submissions ignored the fact that he gave no evidence of having seen a spider on his leg on 9 April 2001 [55]. The evidence only established that Mr Bricknell showed marks on his ankle to Mr Keller. A spider bite was not mentioned until 30 June 2001. The Arbitrator was entitled to consider these matters in declining to draw the inference urged by Mr Bricknell [56]. 4. The following evidence provided by Dr Millar also supported the Arbitrator’s conclusion: (a) the renal biopsy in May 2001 showed significant changes in the renal tubules and Dr Millar said that it was “certainly present for some time prior to this incident in 2001, so that if he had an insect bite, it did not cause his renal problem” [57], and (b) the description of the purpura when Mr Bricknell was in hospital “very strongly suggested the whole problem is one of Henoch-Schönlein purpura rather than an insect bite, which has precipitated his problem” [58]. 5. The Arbitrator’s conclusion was open to him and disclosed no error. 13 Nguyen v WorkCover Authority of New South Wales [2011] NSWWCCPD 55 Employment; identity of worker’s employer; whether employed by an individual or a partnership; whether a partnership existed; credit findings; application of principles in Fox v Percy [2003] HCA 22; 214 CLR 118 Roche DP 29 September 2011 Facts: The issue in this case was who employed the worker. The worker said he was employed by Bong Nguyen (who was uninsured), and claimed compensation from the Nominal Insurer for an injury that occurred on 20 February 2008 when he fell through an open skylight at premises at Cabramatta while he was assisting two men (Bong Kim Nguyen and Hoan Lam Ton) to replace an air-conditioning unit. The Nominal Insurer accepted the claim and paid compensation. A s 145 notice was issued by WorkCover against Mr Nguyen seeking to recover the compensation paid by the Nominal Insurer to or on behalf of the worker. Mr Nguyen filed an application seeking a determination under s 145(3) as to his liability in respect of the payments made. Mr Nguyen is an electrician. He alleged that Mr Ton employed the worker and himself or, in the alternative, a partnership made up of Mr Nguyen and Mr Ton employed the worker. Mr Ton denied employing either the worker or Mr Nguyen. The Senior Arbitrator concluded that Mr Nguyen employed the worker and that there was no partnership or joint venture between Mr Nguyen and Mr Ton. As a result, Mr Nguyen was liable to reimburse the Nominal Insurer for the compensation paid. On appeal, Mr Nguyen submitted that the Senior Arbitrator erred in: (a) (b) (c) (d) (e) finding that Mr Nguyen and Mr Ton were not in partnership; failing to properly assess the employment indicia; his assessment of the worker’s credit; determining that Mr Ton did not pay the worker, and ruling that Mr Nguyen could not amend the application to claim indemnity from Mr Ton for one-half of any liability Mr Nguyen had under the s 145 notice. Held: Arbitrator’s decision confirmed Partnership issue 1. The Full Federal Court held in Amadio Pty Ltd v Henderson (1998) 81 FCR 149 at 179 that “existence of a partnership is determined by reference to the true contract and intention of the parties as appearing from all the facts and circumstances relevant to the relationship of the parties” [38]. 2. For a partnership to exist: a business must be carried on; it must be carried on by persons in common, and it must be conducted with a view to profit (AM Marketing Pty Ltd v Howard Media Pty Ltd [2010] NSWSC 803) [39]. 14 3. Mr Ton carried on a refrigeration and air-conditioning business and agreed with the occupier of the Cabramatta premises that he would replace the air-conditioning unit at those premises. Mr Nguyen played no part in the making of that contract [41]. 4. Mr Ton and Mr Nguyen conducted quite separate businesses and there was no evidence to indicate that Mr Ton regarded Mr Nguyen as his partner. He regarded him as a sub-contractor who provided his skills in exchange for a share of the profits [43]. 5. There was no evidence of any mutuality of rights and obligations: Lang v James Morrison & Co Ltd [1911] HCA 49; 13 CLR 1 at 11 [44]. 6. Even if there was an agreement to share profits, that did not establish the existence of a partnership and did not come from any decision to go into business together. It was agreed machinery for arriving at a sum of money (Haggitt v Watson [1927] NZLR 209 at 230) [49]. 7. There was no agreement to share losses, no evidence of sharing accounts, joint financial statements, common tax file number, common business activity statements, business plans or any other of the indicia of a partnership [50]. 8. The Senior Arbitrator did not err in finding that a partnership did not exist. Employment indicia 9. The issue of who employed the worker was approached by the Senior Arbitrator by a careful analysis of the evidence and application of the accepted legal authorities (in particular, Stevens v Brodribb Sawmilling Co Pty Ltd (1986) 160 CLR 16) to the facts [56] and [66]. 10. For a contract of employment to exist, there must be an intention by the parties to enter into legal relations. Whether a contract has been formed is judged objectively, not by reference to the parties’ subjective beliefs (Lindeboom v Goodwin (2000) 21 NSWCCR 297) [61]. 11. The submission that the Senior Arbitrator failed to have regard to the fact that the project was an air-conditioning installation project, organised by Mr Ton, and not an electrical project, was rejected. That did not mean that the organiser of the project was the employer [66]. 12. The submissions that the Senior Arbitrator failed to give sufficient weight to the fact that Mr Ton was the “driving force, organiser and major profiteer from the project” and failed to have regard to the size and weight of the air-conditioning unit were rejected as they were not decisive or relevant factors in determining who employed the worker. 13. The evidence firmly established that Mr Nguyen employed the worker. The worker’s credit and whether Mr Ton paid the worker 14. The Senior Arbitrator correctly observed that, as the worker’s compensation claim had already been paid, he had no motivation to be untruthful in his answers on crossexamination and his evidence was found to be more acceptable than Mr Nguyen’s and Mr Ton’s evidence [72], [75] and [82]. 15. The worker’s evidence supported the conclusion that Mr Nguyen had employed the worker. 15 16. After a detailed analysis of the evidence and the numerous inconsistencies in Mr Nguyen’s evidence [91]-[98], the Senior Arbitrator rejected Mr Nguyen’s credit concluding that Mr Nguyen was “prepared to say whatever was required, to distance himself from the proposition there was a contract of service between him and the worker”. 17. Having regard to this damning criticism, it was open to the Senior Arbitrator to prefer the worker’s evidence [99]. It also followed from this finding, the worker’s evidence that Mr Nguyen paid him $100 and Mr Ton’s denial of reimbursement of $50 to Mr Nguyen, that it was open to the Senior Arbitrator to find that Mr Ton did not pay the worker [106]. 18. It could not be shown that the Senior Arbitrator “failed to use or has palpably misused his advantage”, or acted on evidence which was “inconsistent with facts incontrovertibly established” or “glaringly improbable” (Devries v Australian National Railways Commission [1993] HCA 78; 177 CLR 472 at 479, 480–481; Fox v Percy [2003] HCA 22; 214 CLR 118 at [25]–[27]) [100]. Amendment 19. The Senior Arbitrator appropriately refused Mr Nguyen’s application to amend to claim an indemnity from Mr Ton for half of any liability he had to WorkCover under the s 145 notice. 20. The Commission’s jurisdiction, like that of the Compensation Court before it, is to hear and determine all matters arising under the 1998 Act and the 1987 Act (s 105 of the 1998 Act) [111]. 21. The Commission is a statutory body that derives its powers from the 1987 Act and the 1998 Act, the Rules and Regulations validly made under those Acts. It does not have any inherent jurisdiction (Raniere Nominees Pty Ltd t/as Horizon Motor Lodge v Daley [2006] NSWCA 235; 67 NSWLR 417) [114]. 22. Even if the partnership argument had succeeded, the Commission did not have jurisdiction to determine the rights and liabilities of the alleged partners. The Senior Arbitrator was right to refuse the application to amend [115]. 16 North Coast Area Health Service v Felstead [2011] NSWWCCPD 51 Personal injury under s 10 of the Workers Compensation Act 1987; disease injury; personal injury; journey incident; failure to give adequate reasons Roche DP 13 September 2011 Facts: Mr Felstead commenced work with the North Coast Area Health Service in 1998. He worked as a truck driver/kitchen hand; generally three days per week driving, and one day per week as a kitchen hand, later changed to two days per week driving, and two days per week as a kitchen hand. On 19 August 2008 Mr Felstead, whilst riding his motorcycle on his journey home from work, collided with a motor vehicle (“2008 injury”). Police were not called to the incident, and Mr Felstead rode home. He attended Lismore Base Hospital where he was treated at the emergency department for an abrasion to the back of his lower left leg and tenderness in his left calf muscle. Mr Felstead was issued with a WorkCover, and following treatment he was discharged. Mr Felstead had four days off from work and then returned to his pre-injury duties. Mr Felstead had several pre-existing medical conditions at the time of the injury. He suffered from left leg sciatica following a hay cart accident in 1984. He conceded that he had a longstanding back condition which he had managed for 11.5 years. He also sustained a left knee injury in November 2006 (“2006 injury”) whilst at work. Liability had been admitted for the 2006 injury; he had undergone surgery, and had recovered, though he states that he continued to feel a dull pain in his left knee. It was Mr Felstead’s submission that he had been able to manage the pain to his knee and back until his accident on 19 August 2008, following which he required medical advice and treatment. Between 22 August 2008 and 21 August 2009 Mr Felstead had several medical attendances where he complained of having difficulty standing for long periods of time, sciatica, lower back pain, and pain to left knee interfering with weight bearing and walking. It was noted on several of the medical certificates that the lower back pain was exacerbated by Mr Felstead’s obesity and his standing for long periods at work (as required by his position as a kitchen hand). During this period (on 24 February 2009) he also sustained a further injury when his right foot was squashed between two pallets (“2009 injury”). The 2009 injury resulted in Mr Felstead relying extensively on his left leg to compensate the injury to his right foot which aggravated his left knee injury. Mr Felstead last worked for the North Coast Area Health service on 21 August 2009. On 2 October 2009 Mr Felstead made a WorkCover application in respect of the 2008 injury. Between 27 August 2009 and 18 June 2010 Mr Felstead undertook further medical examinations in respect of his lower back pain and left knee complaints. Several conditions were identified such as left leg sciatica, degenerative changes to the lumbar spine, and osteoarthritis in his left knee. Medical opinion was diverse in respect of the causes of these conditions. Some medical reports noted that the “left knee was completely normal” [58], and that any knee or back complaints were “related to his obesity” [59]. Other medical reports 17 linked some of the current medical complaints in part to the 2006 injury, and/or 2008 injury. On 11 February 2011 Mr Felstead’s general practitioner, Dr O’Brien, reported that she believed Mr Felstead’s 2008 injury was a “contributing factor to [his] current inability to work”, though she did not detail what injuries had been sustained. The Arbitrator determined that Mr Felstead’s back complaints were not related to the 2008 injury, however he was satisfied his left leg (including his left knee) complaints were. The Arbitrator made an award in favour of the worker in respect of the left leg injury. North Coast Area Health Service appealed this finding on the grounds that the Arbitrator erred in: (a) finding that the reference to “personal injury” in s 10 of the 1987 Act has the same meaning as the definition of “injury” in s 4 of that Act (personal injury); (b) applying the incorrect test in ascertaining whether the worker had received a personal injury to his left knee (personal injury); (c) failing to give proper reasons as to whether the worker injured his left knee in the motor vehicle accident on 19 August 2008 (left knee injury); (d) finding that the worker suffered a personal injury to the left knee in the motor vehicle accident on 19 August 2008 (left knee injury), and (e) relying on the report of Dr Campbell as supporting the proposition that any incapacity from mid-2009 was related to any personal injury to the left knee received in the August 2008 incident (incapacity). Held: The Arbitrator’s decision was revoked and an award granted to the respondent employer. Personal injury under s 10 and s 4 of the 1987 Act 1. Section 10(1) of the 1987 Act states: “A personal injury received by a worker on any journey to which this section applies is, for the purposes of this Act, an injury arising out of or in the course of employment, and compensation is payable accordingly.” 2. Section 4 of the 1987 Act defines an injury as: “injury: (a) means personal injury arising out of or in the course of employment, (b) includes: (c) (i) a disease which is contracted by a worker in the course of employment and to which the employment was a contributing factor, and (ii) the aggravation, acceleration, exacerbation or deterioration of any disease, where the employment was a contributing factor to the aggravation, acceleration, exacerbation or deterioration, and does not include (except in the case of a worker employed in or about a mine) a dust disease, as defined by the Workers’ Compensation (Dust Diseases) Act 18 1942, or the aggravation, acceleration, exacerbation or deterioration of a dust disease, as so defined.” 3. In order to succeed with a claim under s 10 “a worker must have received a personal injury, that is, a sudden identifiable pathological change brought about by an internal or external event. That such a change also causes, or can be characterised as, an aggravation of a disease will not prevent it being a personal injury.” (Yum Restaurants Australia Pty Ltd t/as Pizza Hut Restaurants v Watters [2010] NSWWCCPD 31 (Watters) at [66]). 4. In determining that the worker did sustain an injury, the Arbitrator noted [at [71] of his reasons] that the “two relevant clauses between s 4 and s 10” are “circular and an injury includes a personal injury, and a personal injury includes an injury”. The Arbitrator went on to say “if one is injured on a journey claim, one is injured simpliciter, that is some damage to the body thus it also covers the second limb of sub-paragraph (b) of s 4”. Without defining an “injury simpliciter”, that statement was unhelpful. The question was whether the worker received a “personal injury: on a journey to which s 10 applied. 5. Section 4(b) of the 1987 Act is a reference to a disease injury. It was noted in Watters (at [76]) that: “[t]o establish a disease injury it is necessary that the disease be contracted in the course of the employment and to which the employment was a contributing factor (s 4(b)(i)), or, in the case of an aggravation injury, that the employment was a contributing factor to the aggravation (s 4(b)(ii)). While on a journey, a worker will not normally be in the course of his or her employment and employment will not be a contributing factor to a disease injury. Therefore, to succeed, Ms Watters has to establish that she received a personal injury, that is, a sudden identifiable pathological change.” 6. A worker cannot receive a disease injury (either under s 4(b)(i) or under s 4(b)(ii)) while on a s 10 journey because, in the overwhelming majority of cases, the worker will not be in the course of his or her employment while on such a journey and, in those circumstances, employment cannot be a contributing factor to the contraction of a disease (s 4(b)(i)), or the aggravation of the disease (s 4(b)(ii)) (O’Neill v Lumbey (1987) 11 NSWLR 640. [76] 7. However, a “personal injury” received on a s 10 journey which also aggravates or exacerbates a pre-existing disease is nonetheless a personal injury Zickar v MGH Plastic Industries Pty Ltd [1996] HCA 31; 187 CLR 310 (Zickar). [77] 8. A “personal injury” and a “sudden identifiable pathological change” (Zickar; Kennedy Cleaning Services Pty Ltd v Petkoska [2000] HCA 45; 200 CLR 286 (Petkoska)) test suggests no more than that, to qualify as a personal injury, there must be some sudden and ascertainable or dramatic physiological change or disturbance of the normal physiological state. Such a change or disturbance may be as simple as a bruise or a soft tissue strain. If the personal injury also aggravates a pre-existing disease, that does not mean it is no longer a personal injury [81]. 9. The reference in Petkoska to a “sudden or identifiable” change does not create a disjunctive test, as had been submitted by the worker’s counsel. If an event occurs, such as the rupture of an artery, that will normally qualify as a personal injury even though it is the end result of a disease process. However, if the pathological change is 19 not identifiable or ascertainable, it will obviously be difficult, if not impossible, to establish that the worker has received a personal injury. The reference to identifiable/ascertainable is merely a legal frame of reference to give contextual meaning and sense to “personal injury” [82]. Failure to give reasons 10. Mr Felstead alleged that he injured his back and his left knee in the August 2008 accident. The Arbitrator determined that Mr Felstead had not injured his lower back in the accident on 19 August 2008, and this determination was not challenged on appeal. The Arbitrator did find however, that Mr Felstead had injured his left knee on 19 August 2008. 11. In coming to this conclusion the Arbitrator relied primarily on the evidence of Mr Felstead and Dr Adams’ report prepared on 19 August 2008, wherein both describe that Mr Felstead presented to the hospital with left knee pain. However, upon medical examination, Dr Adams found that Mr Felstead suffered an abrasion to the skin of the posterior lower leg, bony tenderness to the mid tibia, and swelling and tenderness to the left calf. There was no mention of an injury sustained to Mr Felstead’s left knee in Dr Adams’ report. 12. It was argued by North Coast Area Health Service that the Arbitrator had failed to give proper reasons as to whether Mr Felstead injured his knee on 19 August 2008. In order to succeed on this point, North Coast Area Health Service had to demonstrate not only that the reasons are inadequate, but that their inadequacy discloses that the Arbitrator has failed to exercise his statutory duty to fairly and lawfully determine the application (YG & GG v Minister for Community Services [2002] NSWCA 247; Absolon; ADCO Constructions Pty Ltd v Ferguson [2003] NSWWCCPD 21). [93] 13. In determining whether the Arbitrator’s reasons were inadequate, it was noted as per Soulemezis v Dudley (Holdings) Pty Ltd (1987) 10 NSWLR 247 (Soulemezis) at 280 that: “If an obligation to give reasons for a decision exists its discharge does not require lengthy or elaborate reasons: Ex parte Powter; Re Powter (1945) 46 SR (NSW) 1 at 5: 63 WN 34 at 36. But it is necessary that the essential ground or grounds upon which the decision rests should be articulated. In many cases the reasons for preferring one conclusion to another also need to be given.” 14. Roche DP determined that the reasons provided by the Arbitrator as to whether the worker had suffered a personal injury were inadequate. Whilst it was acknowledged that the Arbitrator had referred to the evidence and the submissions in detail, he had merely concluded that he was satisfied that the worker had injured his leg and knee, rather than providing his reasoning supporting this conclusion. [99] Left knee injury 15. An analysis of the various contemporaneous medical reports and examinations showed a focus on an examination of the lower left leg and not Mr Felstead’s knee. The first record of Mr Felstead complaining about left knee symptoms after the bike accident was in Dr O’Brien’s notes dated 25 March 2009 (seven months after the accident). However, those complaints were linked to the 2006 injury [106]. 20 16. Whilst the sudden identifiable pathological change does not need to be significant in order to satisfy the definition of a personal injury, the mere fact that an accident has occurred does not mean that a personal injury has also been sustained [120]. In this instance, the medical evidence supported the fact that Mr Felstead did receive an injury to his left calf and lower left leg, but not to the left knee for which Mr Felstead had claimed workers compensation. 17. On the weight of this evidence and subsequent medical reports, the Arbitrators finding that Mr Felstead had injured his knee on 19 August 2008 was unsupportable. Incapacity 18. In order to recover compensation for an injury, it must be established that the incapacity has resulted from the alleged injury. In a claim for weekly compensation, compensation is not payable for the injury but for the loss of power to earn caused by the injury, that is, for the economic incapacity for work that results from the injury (Williams v Metropolitan Coal Co Ltd [1948] HCA 8; 76 CLR 431 per Starke J at 444; Ward v Corrimal-Balgownie Collieries Ltd [1938] HCA 70; 61 CLR 120 at 129). [84] 19. As Mr Felstead failed to establish that he injured his knee in the bike accident, it was not possible to support a finding of incapacity arising from an injury to the knee. In the alternative, if an injury to the knee was sustained, Mr Felstead had not established that the effect of the injury was continuing or that his incapacity had resulted from that injury [128]. 21 Jetstar Airways Pty Ltd v Canterbury [2011] NSWWCCPD 54 Psychological injury; whole or predominant cause of injury; reasonable action taken with respect to discipline; s 11A of the 1987 Act Keating P 22 September 2011 Facts: Mr Chad Canterbury was employed as a flight attendant by Jetstar. On 4 December 2009, he and a work colleague were “deadheading” on Jetstar flight JQ521 between Sydney and Melbourne. He was not assigned operational duties on flight JQ521. During the course of the flight they were offered refreshments. Mr Canterbury consumed alcohol and confectionary. He gave his credit card to one of the flight crew to pay for the refreshments however the card was not debited and no receipt for the transaction was obtained. On 23 December 2009 Jetstar informed Mr Canterbury he would be investigated for alleged breaches of company policy for consuming alcohol whilst in uniform and on duty, and for the non-payment of the goods. Following an investigation the alleged breaches were sustained and a formal warning was issued. It was common ground that Mr Canterbury suffered a psychological injury. On 8 December 2010, Mr Canterbury lodged an Application in the Commission claiming he sustained psychological injuries. The claim initially relied on the cause of injury being the effects of both the disciplinary action and bullying by his manager. He later withdrew the bullying accusation. On 4 May 2011, the Arbitrator found in favour of Mr Canterbury. He found that Jetstar’s s 11A defence failed as it had not proved that the disciplinary action was the whole or predominant cause of Mr Canterbury’s injury. He also determined that Jetstar’s actions with respect to discipline were not reasonable. Held: Arbitrator’s determination confirmed Whole or predominant cause of injury 1. The onus of proof of establishing any of the matters under s 11A of the 1987 Act falls on the employer (Department of Education and Training v Sinclair [2005] NSWCA 465; 4 DDCR 206; Pirie v Franklins Ltd [2001] NSWCC 167; 22 NSWCCR 346). [116] 2. Mr Canterbury did not concede that his injury was wholly or predominantly due to the actions of the employer with respect to discipline. He merely withdrew the allegation that his psychological injury was caused by allegations of bullying and harassment by his manager. That concession did not relieve Jetstar of the requirement to prove the elements of its s 11A defence that the disciplinary action was the whole or predominant cause of Mr Canterbury’s injury and that its actions were reasonable. [117] 22 3. The Arbitrator’s finding was based on Jetstar’s own evidence in Ms Elphinstone’s report, a psychologist/investigator, that there were several causes of Mr Canterbury’s condition and that at least one of which involved a management issue relating to irregularities in the worker’s sick leave and not the disciplinary action. The Arbitrator’s conclusion that the employer failed to prove that the worker’s injury was wholly or predominantly due to disciplinary action disclosed no error. [125] 4. Whilst there was a temporal connection between the completion of the disciplinary process and Mr Canterbury going off work, the temporal connection did not, of itself, demonstrate that the worker’s psychological injury was wholly or predominantly due to the effects of the disciplinary action. [127] Were the actions of the employer reasonable? 5. Whether an employer’s action was “reasonable” within the meaning of s 11A(1) is an objective test which required an objective assessment of the reasonableness of the action of the employer. If the Commission takes the view that the action taken by the employer is not reasonable in all the circumstances, the employer cannot rely on s 11A merely because it held a genuine belief, based on reasonable grounds, that the action was reasonable (Jeffery v Lintipal Pty Ltd [2008] NSWCA 138 at [50]). [146] 6. Jetstar’s finding that, contrary to policy, the worker was in uniform at the time of the consumption of alcohol was confirmed on appeal to be unreasonable. The finding was against the evidence and the weight of the evidence. Jetstar failed in the course of its investigation to obtain evidence from witnesses who were in a position to give evidence on that issue. [151] 7. Jetstar’s policies and procedures with respect to consumption of alcohol in-flight whilst deadheading were confusing and contradictory. Operating Manual OM 12 permits the consumption of alcohol while on duty, provided the worker is not in uniform. [152] 8. The President rejected Jetstar’s submission that the onus was on the worker to clarify at the time of training any ambiguity regarding any instructions on consuming alcohol during staff travel. The obligation was on Jetstar to communicate its policies and procedures in clear and unambiguous terms. Placing the onus on the worker to clarify its contradictory and confusing policies was an unreasonable response. [153] 9. Jetstar’s submission that the worker was on duty was rejected. Jetstar provided no evidence as to what constituted duty travel and the context in which it appeared led to an inference that whilst deadheading, staff were on duty travel and not duty in the conventional sense. The finding was upheld on appeal. [155] 10. The Arbitrator held that Jetstar’s finding in relation to non-payment was unreasonable. Jetstar’s finding was against the evidence and weight of the evidence. Several witnesses observed Mr Canterbury hand over his credit card to a member of the flight crew. [156] 11. The Arbitrator’s finding that the employer’s actions with respect to discipline were unreasonable, disclosed no error and was upheld on appeal. 23 East Coast Timber Products Pty Ltd v Hancock (No2) [2011] NSWWCCPD 48 Arbitrator erred in failing to give adequate reasons for his decision; determined on remitter from the Court of Appeal NB: This case concerned a review under s 352 before the amendments which took effect on 1 February 2011. Roche DP 1 September 2011 Facts: Mr Hancock was employed as a labourer stacking and sorting timber. He claimed that on 31 October 2005 he fell at work and injured his right knee. He sought medical treatment several days after the fall and did not submit a claim for workers compensation. He alleged that as a consequence of that injury his knee remained troublesome, but he was able to keep working. However, by 2007 he required medical intervention and he ultimately submitted to surgery in June 2008. He has not worked since 25 March 2008. His employment was terminated on 16 October 2008. East Coast disputed that Mr Hancock injured his knee at work on 31 October 2005 and, in the alternative, argued that, if he did injure his knee on that day, he recovered from the effects of that injury and any incapacity had resulted from several later non-work related incidents. Case History: At first instance Mr Hancock was successful and was awarded weekly compensation and benefits for total incapacity. The matter was appealed challenging the Arbitrators finding of injury and incapacity. President Keating found that the Arbitrator had correctly found that Mr Hancock had fallen and injured his knee on 31 October 2005, but that Mr Hancock had failed to discharge the onus of proving his incapacity commencing on 26 March 2008 was a result of the injury sustained on 31 October 2005. In making this determination, President Keating applied Makita (Australia) Pty Ltd v Sprowles [2001] NSWCA 305; 52 NSWLR 705 (‘Makita’) per Heydon JA at [85]. The Arbitrator’s decision was revoked and an award entered for East Coast (see East Coast Timber Products Pty Ltd v Hancock [2009] NSWWCCPD 123). The decision of President Keating was then appealed to the Court of Appeal. There were three main issues on appeal. Firstly that President Keating had erred in his application of the Makita principle. Secondly, that he had failed to draw a Jones v Dunkel (Jones v Dunkel [1959] HCA 8; (1959) 101 CLR 298; [1959] ALR 367) inference in favour of Mr Hancock in respect of East Coast’s failure to supply its own medico-legal experts’ report. Thirdly, that the President had misdirected himself on the issue of causation. The Court of Appeal found that the President had erred in his application of the Makita principle, and therefore did not consider the further issues raised. The Appeal was allowed and remitted to the Commission for redetermination (Hancock v East Coast Timber Products Pty Ltd [2011] NSWCA 11). The matter was remitted to Deputy President Roche who considered the Arbitrator’s failure to provide adequate reasons. 24 Held: The Deputy President confirmed the Arbitrator’s finding that Mr Hancock had injured his knee on 31 October 2005, but because of a lack of reasons, revoked the finding on causation. Consequences of a failure to provide adequate reasons 1. The failure to provide adequate reasons constitutes an error of law and may be a ground to set aside an Arbitrator’s decision [53]. In order to have the decision set aside two elements must be satisfied. Firstly, it must be demonstrated that the reasons were inadequate, and secondly, that the inadequacy shows that the Arbitrator failed to exercise his or her duty to fairly and lawfully determine the application (YG & GG v Minister for Community Services [2002] NSWCA 247; Absolon; ADCO Constructions Pty Ltd v Ferguson [2003] NSWWCCPD 21) [55]. 2. In determining whether reasons are inadequate, the questioner should bear in mind that the standard by which adequacy of reasons must be determined is relative to the nature of the decision itself and the decision-maker (Mayne Health Group t/as Nepean Private Hospital v Sandford [2002] NSWWCCPD 6) [56], and that it is not necessary for an Arbitrator to refer to every piece of evidence (Yates Property Corporation Pty Ltd (in liq) v Darling Harbour Authority (1991) 24 NSWLR 156; Ainger v Coffs Harbour City Council [2005] NSWCA 424) [56]. 3. However, “it is necessary that the essential ground or grounds upon which the decision rests should be articulated. In many cases the reasons for preferring one conclusion to another also need to be given.” (Ex parte Powter; Re Powter (1945) 46 SR (NSW) 1 at 5: 63 WN 34 at 36). [57] Adequacy of Arbitrator’s reasons re: causal event 4. East Coast submitted at the arbitration that Mr Hancock’s failure to contemporaneously report his fall on 31 October 2005, despite his knowledge that he had to do so in order to receive workers compensation, suggested that the event was “trivial in nature” [61]. 5. On the injury issue, the Arbitrator: a) set out Mr Hancock’s evidence; b) referred to corroborative evidence from Mr Hancock’s mother; c) noted the lack of a formal report of injury, but added that a co-worker confirmed that Mr Hancock had mentioned to him that he’d slipped on some timber at work, and d) noted the GP’s records that Mr Hancock had a clearance to return to work “following right knee injury at work”. 6. East Coast argued on appeal that the Arbitrator’s reasons failed to consider the inconsistent dates in Mr Hancock’s statements [66]. 7. This argument was rejected. The starting point in any analysis of whether an Arbitrator has failed to give adequate reasons is to look at the issues in dispute and the submissions made by the parties at the arbitration. If a matter was not argued in the first instance, it is not open to complain on appeal that the Arbitrator failed in his or her 25 duty to give reasons dealing with that matter (Brambles Industries Ltd v Bell [2010] NSWCA 162; 8 DDCR 111) [59]. 8. Given the submissions at the arbitration, namely, that whatever happened on 31 October 2005 was “trivial”, the Arbitrator’s reasons adequately dealt with the issue of injury [66]. Adequacy of Arbitrator’s reasons re: causation 9. East Coast, following its submission that the fall on 31 October 2005 was unlikely to be the causal event, then detailed several subsequent incidents which, it argued, either singularly or jointly may have caused Mr Hancock’s current incapacity. 10. East Coast clearly raised the causation issue and this required the Arbitrator to deal with that issue and give reasons why he felt that Mr Hancock’s condition in 2008 had resulted from the 2005 injury. 11. The Arbitrator had to explain that the pathology diagnosed by Dr Summersell in 2008 had resulted from the 2005 injury [68]. On this critical issue, the Arbitrator did not explain why he preferred Mr Hancock’s evidence to the evidence of several lay witnesses. 12. He merely said that he accepted Mr Hancock’s evidence and that he was persuaded by the medical evidence. That statement did not explain his reasoning process and did not adequately deal with the contentious issue of causation, which depended heavily on the reliability of Mr Hancock’s evidence of having had continuous and increasing symptoms since the October 2005 fall. Where “nothing exists but an assertion of satisfaction on undifferentiated evidence the judicial obligation [to give reasons] has not been discharged” Soulemezis v Dudley (Holdings) Pty Ltd (1987) NSWLR 247 [69]. Was the Arbitrator’s decision correct? 13. It was then considered on the basis that the Arbitrator had failed to provide adequate reasons whether the Arbitrator’s decision was incorrect. 14. Mr Hancock argued that “before ‘disrupting’ the arbitral decision, the Presidential member must be satisfied that the original decision is wrong” (State Transit Authority of New South Wales v Chemler [2007] NSWCA 249; 5 DDCR 286 (Chemler)). It was not sufficient that the Presidential member would reach a different conclusion or would take an alternative view of the facts, if the original decision were reasonably open to the Arbitrator” [18]. 15. This argument succeeded. However, in the absence of sufficient reasons provided by the Arbitrator, and in light of the evidentiary gaps referred to by the Court of Appeal it was not possible to determine whether the Arbitrator’s finding on causation was correct [74]. 16. The finding that Mr Hancock injured his knee on 31 October 2005 was confirmed, but the nature and extent of that injury, and the consequences following from it, were remitted for re-determination by a different arbitrator [75]. 26 Koutsioukis and Koutsioukis t/as Taste of Europe Bakery v Bouza [2011] NSWWCCPD 52 Costs where appellants filed Election to Discontinue Proceedings; s 341 Workplace Injury Management and Workers Compensation Act 1998 Roche DP 14 September 2011 Facts: On 13 December 2006, Arbitrator Simpson found that Mr Bouza, the worker, had suffered a personal injury to his right shoulder on or about 4 June 2001 and another personal injury to the same shoulder on 27 July 2001. She also found that the left shoulder condition was of gradual onset due to Mr Bouza’s work, but rendered symptomatic because of his right shoulder symptoms. He had also suffered an injury to his back as a result of the heavy nature of his work. Mr Bouza’s incapacity was found to have resulted from the second shoulder injury on 27 July 2001. The appellants were uninsured in respect of the period prior to 19 July 2001 and were insured by Employers Mutual after that date. Therefore, Employers Mutual was liable for weekly compensation and the appellants were liable for part of the lump sum compensation. Employers Mutual appealed the Arbitrator’s decision. Moore ADP confirmed the decision and remitted the matter for referral to an AMS. Employers Mutual then appealed the AMS’s assessment to an Appeal Panel. In the absence of the appellants, it was agreed at the post Appeal Panel teleconference on 25 September 2008 that Mr Bouza’s lump sum compensation claim would be paid by Employers Mutual as to $35,000 and by the appellants as to $26,800. WorkCover paid the compensation and costs awarded against the appellants. By service of several notices on the appellants (the last notice was served on or about 17 November 2009), WorkCover sought reimbursement from the appellants under ss 145 and 145A of the 1987 Act. Under s 145(3), the appellants had 28 days from service of the notice to apply to the Commission for a determination of their liability. They did not do this. On 17 August 2010 they unsuccessfully applied to have the Arbitrator reconsider her determination of 13 December 2006. The appellants then sought leave to challenge the Arbitrator’s determinations of 13 December 2006, 30 September 2008 and 15 May 2009 in an appeal filed on 30 August 2010. The appeal was filed over one year outside the 28 day time limit in s 352(4) of the 1998 Act. There were a series of teleconferences held to address the deficiencies in the appellants’s submissions and directions issued to allow for the appeal to be amended and further submissions to be filed and served. The appellants did not comply with any of those directions and ultimately filed an Election to Discontinue Proceedings the day before the matter was listed for hearing. Employers Mutual, in the interests of the third respondents, did not consent to the discontinuance and sought costs in accordance with Pt 15 r 15.7(4) of the 2010 Rules, which are identical to the 2011 Rules. 27 Held: Appellants to pay costs of the third respondents’s insurer 1. The discontinuance of the appeal did not prevent the making of a costs order. The Commission’s Rules expressly contemplate an application for costs in such a situation (Pt 15 r 15.7(4) of the Rules) and are consistent with the practice in the former Compensation Court (see Davis v State Rail Authority (NSW) (2001) 21 NSWCCR 322) [23]. 2. The common law presumption is that costs follow the event. A successful party to proceedings has a “reasonable expectation” of being awarded costs against the unsuccessful party to the proceedings (Oshlack v Richmond River Council [1998] HCA 11; 193 CLR 72 at [134]). A court has a discretion to depart from this presumption, if it is exercised judicially (Donald Campbell & Co Ltd v Pollak [1927] AC 732), and “according to rules of reason and justice” (Williams v Lever [1974] 2 NSWLR 91 at 95) [27]. 3. Generally, it is misconduct on the part of the successful party that is the basis on which the discretion is exercised to displace the presumption (Anglo-Cyprian Trade Agencies v Paphos Wine Industries Ltd [1951] 1 All ER 873 at 874; Ritter v Godfrey [1920] 2 KB 47; Trade Practices Commission v Nicholas Enterprises Pty Ltd (1979) 28 ALR 201) [28]. The appellants’s submission that Employers Mutual engaged in conduct that would disentitle it to a costs order was rejected. Employers Mutual did not have a duty to the appellants in respect of the uninsured period. The fact that the appellants had not been notified of the hearing before the Arbitrator was not determinative of the costs question [29]. 4. Section 341 gives the Commission a broad discretion to determine questions relating to costs [34]. Section 341(4) expressly alters the common law presumption that costs follow the event, as it prevents the Commission from making an order for costs against an unsuccessful claimant unless the claim was frivolous or vexatious, fraudulent or made without proper justification. Insurers and employers do not have the protection of s 341(4), as they are not persons entitled to make a claim for compensation or work injury damages [35]. 5. Section 341 must be read with s 337 of the 1998 Act [36]. Part 17 of the 2010 Regulation regulates costs in the Commission. Schedule 6 to the 2010 Regulation sets out the maximum costs that are recoverable for legal services provided in or in relation to a claim for compensation [37]. 6. Clause 100(4) of the 2010 Regulation states that if an appeal is lodged in respect of a claim or dispute, no amount for costs is recoverable unless the appeal is determined, is withdrawn or lapses [38]. 7. The appeal was “withdrawn” by the appellants filing an Election to Discontinue and therefore costs were recoverable [39]. 8. Even though the uninsured employer lodged the appeal application, the Commission had power to order costs in favour of the employer’s insurer. The reference to insurer in Sch 6 includes an employer (cl 94 Div 1 Pt 17) [42]. 9. Though the third respondents had not incurred any costs against the appellants, it was open to make an order in their favour (McCullum v Ifield [1969] 2 NSWR 329, applied in Dyktynski v BHP Titanium Minerals Pty Ltd [2004] NSWCA 154 at [77]) [45]. 28 10. However, it was appropriate for the costs order to be made in favour of Employers Mutual because it had a right of subrogation to enforce any order made in favour of its insured, a reference to insurer in Sch 6 includes an employer and it had a direct interest in the litigation (Knight v F P Special Assets Ltd [1992] HCA 28; 174 CLR 178 at [34]) [45]. 29