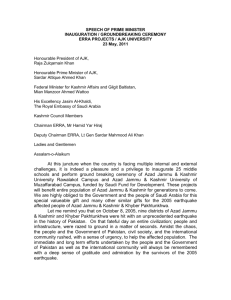

US Department of State

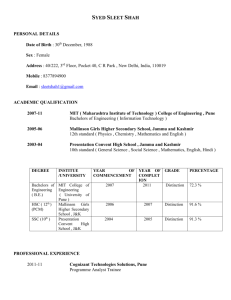

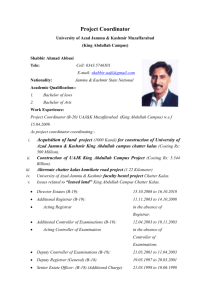

advertisement