The Coffeehouse Culture in Vienna: From Sieges

advertisement

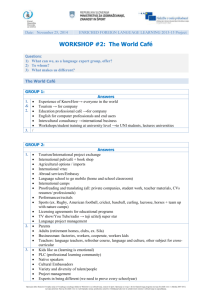

Seth Fowler 1 The Coffeehouse Culture in Vienna: From Sieges to Central "Du hast Sorgen, sei es diese, sei es jene - - ins Kaffeehaus!" "Sie kann, aus irgend einem, wenn auch noch so plausiblen Grunde, nicht zu dir kommen - -ins Kaffeehaus!" „Du hast zerrissene Stiefel - - Kaffeehaus!" „Du hast 400 Kronen Gehalt und gibst 500 aus - - Kaffeehaus!" „Du bist korrekt sparsam und gönnst Dir nichts - - Kaffeehaus!" „Du bist Beamter und wärest gern Arzt geworden - - Kaffeehaus!" „Du findest Keine, die Dir passt - - Kaffeehaus!" „Du stehst innerlich vor dem Selbstmord - - - Kaffeehaus!" „Du hasst und verachtest die Menschen und kannst sie dennoch nicht missen -Kaffeehaus!" „Man kreditiert Dir nirgends mehr - - Kaffeehaus!" von Peter Altenberg Seth Fowler February 3, 2006 Professor Anne Ulmer German 346 Seth Fowler 2 Coffee and cafés are a pervasive part of today’s Western culture with millions of people visiting these establishments every day. It is no surprise, then, that chains and franchises like Starbucks have seen an incredible expansion of demand all over the world. While coffee as a drink and all its various incarnations are certainly a part of their popularity, there is another, more historical legacy to the café and its precursor, the coffeehouse. The coffeehouse has a special reputation associated with it that has nothing specifically to do with coffee, but instead one can envision it as a place of conversation and gathering, of intellectuals and thinkers, of writers and poets. This is the legacy of the coffeehouse and the reason so many young professionals (or yuppies as they are most often called), college students and others now flock to cafés, and it is a legacy that started in Vienna in the 1600s and reached its golden pinnacle during Vienna’s defining fin-desiecle period of 1880 – 1920. Viennese history is a long and illustrious one, in no small part because of the Austro-Hungarian Empire that dominated Central Europe for hundreds of years. From both a modern and far-sighted view of history, the turn of the century was a pivotal part of Vienna’s past, and the ideas and culture fostered there, within Vienna and centered around the intellectualism of the coffeehouse, changed the whole world. People like Sigmund Freud, Arthur Schnitzler, Peter Altenberg, Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele, Karl Kraus, and so many more were constant inhabitants of one coffeehouse or another and were widely known to be found there smoking and reading and conversing more often than in their homes or places of work. Seth Fowler 3 The world of coffeehouses is an idiosyncratic one, filled with connoisseurs who expect things just so, and subtle distinctions as to who should sit with whom, times for thinking and times for leisure and requesting exactly by what process the coffee should be brewed to reach the preferred color, strength, consistency, etc. It is from these subtle distinctions that one draws a fine line between cafés and coffeehouses. This may be an entirely moot point in today’s world of instant coffee, iced frappe-mocha-cinos and Starbucks, but at the time, these institutions were filled with denizens who had their very own way of seeing a coffeehouse. Some like Friedrich Torberg and Peter Altenberg, Café Central’s perennial resident, even wrote short treatises on the intricacies of coffeehouses or the rules one should follow while sitting at a table in fine company. Café or coffeehouse, then, what is the difference? The answer is one of emphasis. In a café, one is there, ultimately, to get a drink of coffee or some other sort of new age beverage, whereas in a coffeehouse, the coffee is more of a means rather than an end and acts as a social institution that is difficult to measure simply by the material services it provides (Heering 13)1. Friedrich Torberg, within his “Traktat über das Wiener Kaffeehaus” makes the same distinctions but with different terms: the Kaffeehaus instead of the café, the Literatencafé instead of the coffeehouse (Torberg 26-7)2. The meanings, however, are the same and with the beginning of the First World War the era of coffeehouses was complete. A visit to a café is typically rushed and efficient. One sits just long enough to enjoy a drink but soon feels obligated to make further purchases to justify a longer, more 1 Heering, K.-J. (1993). Das Wiener Kaffeehaus : mit zahlreichen Abbildungen und Hinweisen auf Wiener Kaffeehäuser. Frankfurt am Main, Insel Verlag. 2 Torberg, F. (1993). Traktat über das Wiener Kaffeehaus. Das Wiener Kaffeehaus : mit zahlreichen Abbildungen und Hinweisen auf Wiener Kaffeehäuser. K.-J. Heering. Frankfurt am Main, Insel Verlag: 1832. Seth Fowler 4 leisurely stay. The process smacks of Western service, so hurried and expeditious, and can be, on the whole, a cheapened experience. Get in, get served, and get out. The real Viennese coffeehouses were certainly busy places and filled with activity, but they were also places of habitation where one was sincerely expected to spend hours reading, writing, conversing, or any matter of things. In Vienna today, patrons can still be expected to while away the hours within a coffeehouse unharried and unobligated to bother with even the waiter until they choose to leave, or perhaps, until the establishment closes for the evening. This behavior is encouraged in finer coffeehouses, where the waiters will periodically bring a small complimentary glass of water. In fact, it would be “ridiculous to order more than one coffee per morning or afternoon” (Augustin 4)3. To make all of this slightly more confusing, most, if not all, of the traditional and famous coffeehouses, Torberg’s ‘Literatencafés’, all use the word Café within their name: Café Griensteidl, where an entire literary movement began, once destroyed and later rebuilt; Café Central, arguably the most famous of the coffeehouses with its rich history of famous authors, scientists, and revolutionaries; Café Museum designed by Vienna’s own Adolf Loos; not to forget Café Herrenhof, Café Hawelka, Café Imperial, Café Landtmann, and a dozen others. These Cafés, despite the obvious semantic arguments, are all coffeehouses. Friendly waiters and traditional marble topped tables, however, do not an intellectual and cultural institution make. Torberg asks: “Warum is es das nicht mehr? Auch für jene nicht, die konsitutionell dafür geeignet wären? Liegt es an ihnen, daß sie im Kaffeehaus nicht mehr arbeiten können? Liegt es am Kaffeehaus?” (28). 3 Augustin, A. Das Cafe Central Treasury: Geheimnisse eines berühmten Kaffeehauses/Secrets of a Famous Coffee House. London?, The Most Famous Hotels in the World, 2003. Seth Fowler 5 And he is correct when he says, “Es liegt an ihrer Arbeit. Es liegt an der Technik… Politik und Soziologie…” und so weiter (28). Timing, it seems, was just as important a factor in the development of coffeehouse culture as anything else. Taken from a more holistic and historical standpoint, the development of the heavily intellectual coffeehouse culture of Vienna during the fin-de-siecle period was the result of the combination of all the right things. A number of prominent Viennese citizens and guests were attracted to the social scene presented at the coffeehouses because of the atmosphere they created. In a time where houses were built more for show than for comfort and things like central heating were far from standard, the amenities of a coffeehouse made it a warm and appealing place to spend one’s time. It was a place of connections both intellectual and social where friends could meet, plans were made, and one could read the happenings of the world from the dozens of different newspapers available. With the advent of cellphones, the internet and before them, the popularization of the telephone, it is easy to forget about a time when such easy access to world events and personal communication was more or less impossible. Therefore the coffeehouse served as Vienna’s most important and consolidated third place—a place “that host[s] regular, voluntary, informal, and happily anticipated gatherings of individuals beyond the realms of home and work” (Oldenburg 16)4. Institutions such as these serve important yet difficult to measure sociological functions. On the most basic of levels, a coffeehouse exists to serve coffee and ultimately turn a profit, but as a third place, it fulfills a separate, unintended function. The most important of these functions is the sustaining and building of civil society, which is a concept used 4 Oldenburg, R The Great Good Place: Cafes, coffee shops, community centers, beauty parlors, general stores, bars, hangouts and how they get you through the day. New York, Paragon House, 1989. Seth Fowler 6 to measure the extent of tolerance, helpfulness, and friendliness of one citizen to another. To make it simpler, coffeehouses add character. The Origins of the Coffeehouse: The Second Turkish Siege and the Battle of Vienna The arrival of coffeehouses to Vienna is no less legendary than the culture that eventually grew to surround them. The Ottomans had long wanted to capture Vienna, a city Johann Martin Lerch described as “[d]as Haupt Europae, das Teutsche Rom, eine Käyserin der Städte, der Welt Lust-Hauß,” the capital of the Habsburg Empire and as a gateway to the rest of Europe (qtd. in Oberzill 11)5. In July of 1683, 154 years after the first Ottoman attempt to take the city, Vienna found itself again beset by an army 200,000 strong with few defenses outside the city walls (Augustin 13). After two months, the city was in dire need of help. Enter Kolschitzky, an Arabic-speaking Pole, who was sent out of the city through the enemy lines to deliver messages asking for desperately needed aid (Sinhuber 7)6. Kolschitzky was sent on additional missions, and although he was not the only secret messenger sent from Vienna, he did become the most famous (8). Two months after the siege had started, help arrived. On September 12th, 1683, 70,000 men primarily under the command of King Jan III Sobieski of Poland and others, including Emperor Leopold I, took the Ottoman army by such surprise that the opposing army fled, leaving most of their supplies on the battlefield (13). Kolschitzky, having been duly rewarded with 200 ducats and special property rights for each of his missions, requested to keep the large sacks of beans that had been 5 Oberzill, G. HIns Kaffeehaus! : Geschichte einer Wiener Institution. Munchen, Jugend und Volk, 1983. Sinhuber, B. F. Die Wiener Kaffeehausliteraten: Anekdotisches zur Literaturgeschichte. Wien, DachsVerlag GmbH., 1993. 6 Seth Fowler 7 left behind (16). At this point, sources differ as to how much of a role Kolschitzky played in the founding of the first (documented) coffeehouse. Some say his role stopped here, others say he did eventually start a coffeehouse or two, or maybe that he simply helped teach others how to brew coffee. While the legend of Kolschitzky is very popular and found in a variety of sources, it is told more out of a love for the story and respect for tradition than any actual basis in truth. Other epicurean legends surrounding the Battle of Vienna of 1683 include the invention of both the croissant and the bagel. The croissant is more firmly established as a fabrication, but a fanciful one. A baker, wanting to celebrate the defeat of those who wanted to threaten Christendom, crafted a pastry in the form of a crescent, the symbol of Islam. The truth is that it most likely originated in France a century later, hence its French name. The origins of the bagel are more questionable. It is certainly Central European and was most likely made by a Polish Jew. Whether the invention took place in Vienna at the time of the siege—the shape of the bagel mimics, somewhat correctly, the shape of the stirrups used by the Ottoman cavalry—or whether it simply gained popularity in Vienna is much more difficult to discern. A more truthful account of Vienna’s first coffeehouse involves a Greek named Johannes Diodato, who also served as a secret messenger for Vienna during the siege and was accorded similar rights and rewards as Kolschitzky. Additionally, in January of 1685, Kaiser Leopold I granted Diodato the exclusive right to serve coffee and therefore operate a coffeehouse (Sinhuber 8). The similarities between the two stories, that they are both foreigners, were both successful spies, had a previous knowledge of coffee, and were rewarded with property rights, are highly interesting, but there is no real Seth Fowler 8 documentation of Kolschitzky’s activities after the war, except for the hearsay that has persisted to this day. Diodato’s coffeehouse, which quickly adopted the very novel idea of adding milk to coffee, was, needless to say, a success. Despite the success of the King Sobieski and the hasty retreat of the Turks, Vienna was conquered—by Turkish coffee, by their culture. Café Griensteidl, “dessen Licht bis in unsere Tage herüberstrahlte”7 There were well known coffeehouses before Griensteidl made its appearance. By 1794, barely a century after Diodato’s first establishment opened, there were over 64 different coffeehouses in Vienna (Augustin 17). That was also the year that the first socalled literary café opened, Café Kramer am Graben. Café Kramer and others like it eventually led to the development of places like Neuner’sche Kaffeehaus, the first of the literary cafés to attract its own famous clientele group (in this case, the Biedermeier authors Grillparzer, Lenau and others) (19). Neuner’s success led him to create an extravagant coffeehouse known as Das Silberne Kaffeehaus, which was, appropriately enough, equipped with silver trays, cups, doorknobs and hangers (19). This set a precedent of opulent and elegant coffeehouses and quite easily made the Silbernen Kaffeehaus the most famous coffeehouse of Vienna. At least, that is, until Heinrich Griensteidl came along and created something truly amazing on the ground floor of Palais Dietrischstein am Michaelerplatz (Sinhuber 102). Griensteidl was a pharmacist turned Kaffeesieder, or barrista, who decided to relocate his first coffeehouse to the very prominent location adjacent to the Hofburg on 7 “Whose light shone into our days” (Oberzill 85). Seth Fowler 9 the corner of Herrengasse in the middle of the city (102). Newspapers were becoming more and more popular among most urban citizens, and while most coffeehouses did have some print materials, Griensteidl greatly expanded upon this theme. In “Jugend im Griensteidl,” a chapter of Die Welt von Gestern, Stephan Zweig writes of “nicht nur die Wiener [Zeitungen], sondern die des ganzen Deutschen Reiches und die französischen und englischen und italienischen und amerikanischen, dazu sämtlichene wichtigen literarischen und künstlerischen Revuen der Welt…. So wußten wir alles, was in der Welt vorging, aus erster Hand…” (Zweig 39)8. Zweig’s account tells of two related yet important facets of the growing coffeehouse culture. The first was the absolute need to be aware of modern events. Places like Café Griensteidl were filled with Very Important People, some of whom were truly important, and some of whom were self-inflated egos, but regardless, Very Important People tended to discuss Very Important Things, and these things, these world events, could only be gleaned from the newspapers of the world. Secondly, it is necessary to note and underscore the importance of Judaism to Vienna and to the unique culture of coffeehouses during this time. Assimilation in Viennese culture was widespread and encouraged, in part “to escape the commercial existence which has been supposed natural to them” (Schorske 149)9. The result of this is a “liberal, urban middle class” that was not exclusively Jewish but highly valued among the Jewish intellectual class (148). The list of famous Jewish names is a long one including: Peter Altenberg, Gustav Mahler, Arthur Schnitzler, Sigmund Freud, Stefan Zweig, and dozens of others. None of these men necessarily identified themselves as Jewish, but Jewish they were and it had an impact on their upbringing and, as certain as it 8 Zweig, S.”Jugend im Griensteidl.” In: Das Wiener Kaffeehaus: mit zahlreichen Abbildungen und Hinweisen auf Wiener Kaffeehäuser. Frankfurt am Main, Insel Verlag, 1993. 9 Schorske, C. E. Fin-de-Siecle Vienna: Politics and Culture. New York, Vintage Books, 1981. Seth Fowler 10 is unfortunate, the later parts of their lives as Vienna and Europe gradually became more and more anti-Semitic. In 1848, amid a revolution against the struggling monarchy, Café Griensteidl was temporarily nicknamed Café National as a reflection of the intellectual sympathies of its patrons (Oberzill 86). After the revolution ended and the city’s nationalism faded, the Café regained its original name. That is not to say that all of the intellectuals of Griensteidl were of one mind. In fact, two of Griensteidl’s most famous inhabitants were both extreme radicals whose ideas had quite a brutal impact on the world. A great number of the intellectuals who frequented the coffeehouses were writers or one sort or another. There were scientists and philosophers, too, who also produced their fair share of written materials. Griensteidl was popular among the actors who came from the nearby Burgtheater, and any place with so many somebodies is bound to have a politician or two. Georg Ritter von Schönerer was particularly fond of taking his coffee there on Michaelerplatz (86). Schönerer used his considerable influence to spread his Pan-Germanic platform and the same virulent anti-Semitic ideology that eventually gained influence among other native Austrians like Karl Lueger and Adolf Hitler (Schorske 119). His fame subsided somewhat after he raided a Jewish editorial office and assaulted a number of workers, leading to a short jail sentence and a ban on his political rights for five years (131). Curiously enough, Schönerer was not the only person with some radical ideas about the Jewish population to be found in Café Griensteidl. Theodor Herzl was known to work as the Feuilletonredakteur for the Neue Freie Presse, a well-respected position with Austria’s major newspaper (Oberzill 86). Herzl’s position as a journalist gave him a Seth Fowler 11 unique political viewpoint during a time when Jews were threatened by Pan-Germanism and the Christian Social Party. It was during this pivotal and turbulent time that he wrote and published The Jewish State which outlined the ideals and objectives of Zionism (Schorske 162, 166). Herzl hoped that Zionism would ultimately solve the problem of anti-Semitism and the pressure to assimilate. If there was a legitimate Jewish nationstate, they could establish rights on their own terms and no longer be subject to the whims of the sentiments of other nations. Café Griensteidl was also the meeting point for a grand collection of Vienna’s most talented and most ambitious writers, granting it the privilege of being the first coffeehouse entitled Café Größenwahn10 (the other two coffeehouses being Café Central and the Romanische Café of Berlin, each in their respective heyday) (Sinhuber 105). Several of Vienna’s most well-loved authors first started their professional careers from the classic marble tables occupied by Hermann Bahr, Felix Salten, Richard BeerHofmann, Karl Kraus, a very young Hugo von Hofmannsthal, and many others. Some were beloved, especially Hermann Bahr and Beer-Hofmann, and others, like the young Mr. Kraus, were just starting. Nothing, sadly, lasts forever, and in 1897 Café Griensteidl closed its doors (111). The announcement came from Susanne, the widow of Heinrich Griensteidl, and was hugely unpopular. The outcry provided the perfect opportunity for a young, 23-year-old Karl Kraus to publish his first truly satirical work “Die demolirte Literatur” (112). Kraus wrote the piece as a critique of the strange dependence that the so many of the Viennese 10 Größenwahn means something similar to ‘illusions of grandeur’ or megalomania. Seth Fowler 12 authors had on the coffeehouse, and in doing so, he managed to define the same literary movement. “Die moderne Bewegung, die vor einem Jahrzehnt vom Norden ausging, hat hier nur rein technische Veränderungen hervorgerufen. Vor der inneren Wirkung neuen Styls, der das Stoffgebiet erweitern half und sociale Probleme ins Rollen brachte, ist unsere junge Kunst verschont geblieben, die geradezu in der Abkehr von den geistigen Kämpfen der Zeit ihr Heil sucht” (Kraus 70)11. The writers of this “demolished literature” were all members of the Jung-Wien movement, and his brief essay helped to clarify their position. Kraus thereby managed to separate himself somewhat from the Jung-Wien group and became more and more a constant, critical reminder of the way the people and writers in Vienna were truly perceived. Satire aside, “Die demolirte Literatur” did bring to a head a very important dilemma: now that Vienna’s most famous coffeehouse was closing, the Café National, the Café Größenwahn, where was everyone, including Kraus, to go? Café Central: The Grandest One of All In 1867, just down the road on Herrengasse, the Pach brothers had opened Café Central in a place that was once used as a commodity exchange (Augustin 33). Its location, a short walk from the Griensteidl, made it all the easier for the misplaced authors of Café National to relocate. Kraus was one of the first well-known personalities to establish a presence there, where he wrote Die Fackel, a magazine critical of Viennese culture and society that was produced, edited, and largely written by himself. After 1911, Die Fackel was written exclusively by Kraus until his death in 1936. 11 Kraus, K. Die demolirte Literatur. Das Wiener Kaffeehaus : mit zahlreichen Abbildungen und Hinweisen auf Wiener Kaffeehäuser. K.-J. Heering. Frankfurt am Main, Insel Verlag, 1993. 60-87. Seth Fowler 13 More and more Viennese intellectuals, including those from the Jung-Wien movement, found themselves in Café Central, much to Kraus’ chagrin. Even though he referred to them as “das ganze Rudel ‘Talentloser’ [im] Central,” he still associated with them somewhat, and a few even wrote for Die Fackel when Kraus was still soliciting articles from other writers (Oberzill 95). Schönerer and Herzl relocated there, as did Schnitzler, Hofmannsthal, Salten, Beer-Hofmann, and Bahr (Augustin 37, 47). Café Central had its own politicians as well, including Thomas Masaryk, who quit frequenting the coffeehouse after he became the first president of Czechoslovakia (37). Adolf Loos was another fan of Café Central, even though he eventually designed his own coffeehouse, Café Museum on Karlsplatz which attracted its own set of Secessionist followers, like Klimt and Schiele, as a credit to its design and proximity to the Secessionist building (39). The early 19th century was also a time of Bohemians and revolutionaries, and a place like Café Central was the keystone to same very interesting developments. Known as an avid chess player, Lev Bronstein could be found in Café Central from 1907 until he fled the city during World War I (Sinhuber 54). In his autobiography, he tells of first meeting the famous social democrats Viktor and Friedrich Adler and Rudolf Hilferding and remembers “mit lebhaftestem Interesse [ihre ernste] Unterhaltung im Café Zentral” (Trotzki 163). Lev was also known for his association with two other men. One, Vladimir Illyich Uljanov, was also a known regular, and on occasion both met with a third, Iosif Vissarionovich Dzhugashvili, a mastermind and eventual tyrant (Augustin 44). Here were some proper revolutionaries, throwing ideas back forth between cups of mélange. Seth Fowler 14 In 1917, after the Russian Revolution, the Austrian prime minister, Heinrich Graf ClamMartinic is reported to have said, “Eine Revolution in Rußland? Ja, wer soll denn die gemacht haben, vielleicht der Herr Bronstein aus dem Café Central?” (Sinhuber 54). Their names, long and consonant-ridden, are not so well known today, or at least, not in the forms they carried in Vienna. Dear Mr. Bronstein was eventually exiled and killed following a power struggle with Dzhugashvili. Of course, by that time Bronstein was the very famous Leon Trotsky, whose eventual downfall and assassination was caused by Dzhugashvili, better known as Joseph Stalin. And Vladimir Uljanov, friend and regular, was none other than Lenin (Augustin 44). Not everyone within Café Central was overturning governments and inciting rebellions. Some were simply witty entertainers, the darlings of the coffeehouse. The Stammgast of Stammgäste in Café Central was Mr. Peter Altenberg, whose likeness can still be found there today in the form of a hand-painted plaster effigy just inside the door. His real name, Richard Engländer, was dropped in favor of his nom-de-plume, and he was one of several discoveries whose talents were brought about almost specifically by coffeehouse culture (Sinhuber 108). Almost no book to be found on coffeehouses can go without mentioning Altenberg, and more than that, his famous poem “Kaffeehaus” is a popular opener, closing, and example of all the great things about those who love the coffeehouse. The poem mostly posits the coffeehouse as the solution to whatever a man’s problem may be. Seth Fowler 15 “Du hast Sorgen, sei es diese, sei es jene---ins Kaffeehaus!/…Du hast 400 Kronen Gehalt und gibst 500 aus---ins Kaffeehaus!” and so on (Altenberg 17)12. Altenberg’s literature or works is not as highly valued today as those of many of his contemporaries, many of whom were also to be found sharing a table with him from time to time. Despite this, he was an invaluable asset to the productive forces generated within Café Central. He was a “Bohemien und lebte von der Hand in den Mund,” but also a “Schwärmer, sah aus wie ein trauriger Clown” (Kokoschka 139)13. His lifestyle, antics, and serious manner of living life the way he wanted, which was not too seriously, put him in a group that “gehörte zu den besonders geschätzten Freunden von Adolf Loos und Karl Kraus, die ihm lebenslang treu geblieben sind” (138). All of this, Oskar Kokoschka writes in “Karriere im Café Central,” which is a loving account of the relationships and careers he saw formed there. His own, even, was encouraged by his developing friendship with Adolf Loos, whom he held in the highest esteem, and who even told him once, “Du mußt malen!” (128). As a mirror to the love and appreciation Café Central and its denizens had for Peter Altenberg, stands the fanatical devotion Alfred Polgar had for Café Central. “Das Café Central ist nämlich kein Caféhaus wie andere Caféhäuser, sondern eine Weltanschauung” begins his “Theorie des Café Central” (Polgar 149)14. He goes on to defend this notion in a way that is very true to much of what went on within Café Central. 12 In this case, the poem was used as a prologue in a book titled Das Wiener Kaffeehaus, but it also quoted in full in Oberzill as well as printed on the back cover, and part of almost any anthology that covers the time period. Please also note the cover page. 13 Kokoschka, O. Karriere im Café Central. Das Wiener Kaffeehaus : mit zahlreichen Abbildungen und Hinweisen auf Wiener Kaffeehäuser. K.-J. Heering. Frankfurt am Main, Insel Verlag, 1993, 128-40. 14 Polgar, A. Theorie des Café Central. Das Wiener Kaffeehaus : mit zahlreichen Abbildungen und Hinweisen auf Wiener Kaffeehäuser. K.-J. Heering. Frankfurt am Main, Insel Verlag, 1993, 149-54. Seth Fowler 16 To Polgar, Altenberg and their ilk, Café Central was a place whose very faults were charms greater than all the merits of any other place they could be. Polgar considered himself a Centralist, that is, a certain class of people who not only had the irrefutable sense to become regulars of Café Central and take part in its social world, but a Centralist is aware of the superiority and comfort of Café Central to the point that “[g]anz erfassen wird das ja nur ein richtiger Mensch, der, ist sein Kaffeehaus gesperrt, die Empfindung hat, ins rauhe Leben hinausgestoßen zu sein, preisgegeben den wilden Zufällen, Anomalien, und Grausamkeiten der Fremde” (149). As intellectual and diverse as the coffeehouses were, they were an insulating cultural sphere. To leave the comparative comfort of the coffeehouses was to enter the tumultuous political culture of Vienna in a direct fashion. To stay inside the coffeehouses was naïve perhaps, but it allowed for an environment of free thought and Bohemian ideals—a last cultural hurrah before the Great Wars. The Beginning of the End and Other Stories 1919 was a bad year, generally speaking, and it was especially rough for all of those involved in the relative ease and high-mindedness of the coffeehouses. The deaths of the previous year, due to war and influenza, of Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele, Koloman Moser, Otto Wagner and others were taking their toll on the life and character of Vienna. Peter Altenberg died and with him went much of the shine of Café Central. The era of coffeehouses had passed its peak. Karl Kraus and much of his crowd lingered on in Café Central until old age or turbulent political conditions necessitated otherwise. What was left of the intellectual Seth Fowler 17 movement of Café Central, which was still quite significant, moved to Café Herrenhof, another candidate for the title of Größenwahn. But to focus only on these coffeehouses is to do a disservice to the ubiquity of establishments similar in nature and ones that were also quite significant but lacked the same reputation of Griensteidl, Central or Herrenhof. As mentioned previously, Loos had designed a coffeehouse popular with the Secessionists, the Café Museum. Café de l’Europe and Café Imperial both had important Stammtische of sorts, as more and more Germans, like Bertolt Brecht, Oskar Maria Graf, and Walter Mehring, fled the troubles of their homeland. Kraus’ statement on the subject was, “Die Ratten betreten das sinkende Schiff” (Augustin 55). There were also Café Landtmann, Café Hawelka, Café Sperl, and hundreds of others. In the beginning of the 19th century there were over 600 different coffeehouses and cafés among half a million or so Viennese (33). Each of these places has its own story, its own significance that resided within each of its particular inhabitants. There are anecdotes and poems and entire works of fiction about coffeehouses, and all of these works and collective memories serve to show a grander picture of how unique a phenomenon existed in Vienna. Coffeehouses let the city express its social life through dialogue and discussion, open to a great variety of people, and were, for better or for worse, oblivious to the ominous occurrences in the world outside Polgar’s restricted Weltanschauung. “Der Centralist,” Polgar wrote, but it most assuredly applies to all of the Stammgäste of Vienna, “lebt parasitär auf der Anekdote, die von ihm umläuft. Sie ist das Hauptstuck, das Wesentliche. Alles übrige, die Tatsachen seiner Existenz, sind Kleingedrucktes, Hinzugefügtes, Hinzuerfundenes, das auch wegbleiben kann” (Polgar 152). Seth Fowler 18 His words are reminiscent of a legendary time, the truth of which is, or maybe should be, obscured but the telling of which is itself important. For a time that led to so much pain and suffering, it is not surprising to see such a romantic thought, and so much written and discussed during and about that time honors the sentiment. Including this paper. Seth Fowler 19 Bibliography Augustin, A. Das Cafe Central Treasury: Geheimnisse eines berühmten Kaffeehauses/Secrets of a Famous Coffee House. London?, The Most Famous Hotels in the World, 2003. Heering, K.-J. Das Wiener Kaffeehaus : mit zahlreichen Abbildungen und Hinweisen auf Wiener Kaffeehäuser. Frankfurt am Main, Insel Verlag, 1993. Kokoschka, O. “Karriere im Café Central.” In: Das Wiener Kaffeehaus : mit zahlreichen Abbildungen und Hinweisen auf Wiener Kaffeehäuser. K.-J. Heering. Frankfurt am Main, Insel Verlag, 1993, 128-40. Kraus, K. “Die demolirte Literatur.” In: Das Wiener Kaffeehaus : mit zahlreichen Abbildungen und Hinweisen auf Wiener Kaffeehäuser. K.-J. Heering. Frankfurt am Main, Insel Verlag, 1993, 60-87. Oberzill, G. H. (1983). Ins Kaffeehaus! : Geschichte einer Wiener Institution. Munchen, Jugend und Volk. Oldenburg, R. The Great Good Place: Cafes, coffee shops, community centers, beauty parlors, general stores, bars, hangouts and how they get you through the day. New York, Paragon House, 1989. Polgar, A. Theorie des Café Central. In: Das Wiener Kaffeehaus : mit zahlreichen Abbildungen und Hinweisen auf Wiener Kaffeehäuser. K.-J. Heering. Frankfurt am Main, Insel Verlag, 1993, 149-54. Schorske, C. E. Fin-de-Siecle Vienna: Politics and Culture. New York, Vintage Books, 1981. Segel, H. B. The Vienna coffeehouse wits, 1890-1938. West Lafayette, Ind., Purdue University Press, 1993. Sinhuber, B. F. Die Wiener Kaffeehausliteraten: Anekdotisches zur Literaturgeschichte. Wien, Dachs-Verlag GmbH., 1993. Torberg, F. (1993). “Traktat über das Wiener Kaffeehaus.” In: Das Wiener Kaffeehaus : mit zahlreichen Abbildungen und Hinweisen auf Wiener Kaffeehäuser. K.-J. Heering. Frankfurt am Main, Insel Verlag, 1993, 18-32. Trotzki, L. Erstaunen im Cafe Central. Lokale Legenden: Wiener Kaffeehausliteratur. H. Veigl. Wien, Kremayr & Scheriau, 1991. Seth Fowler 20 Veigl, H. Lokale Legenden : Wiener Kaffehausliteratur. Wien, Kremayr & Scheriau, 1991. Zweig, S. “Jugend im Griensteidl.” In: Das Wiener Kaffeehaus: mit zahlreichen Abbildungen und Hinweisen auf Wiener Kaffeehäuser. Frankfurt am Main, Insel Verlag, 1993.