Lecture 2 (Chapter 2)

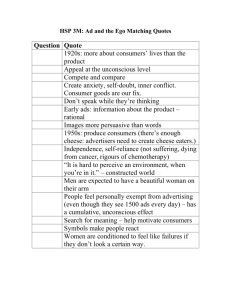

advertisement

Lecture 2 (Chapter 2) Labor Productivity and Comparative Advantage: The Ricardian Model Differences in the technology of production Let us consider the example of trade between Portugal and England, as described by David Ricardo. Ricardo considered just two commodities, wine and cloth. Ricardo allowed Portugal to have an absolute advantage in the production of both goods. Portugal’s absolute advantage may reflect, for example, its more favorable climate for both growing grapes and grazing sheep. Even though Portugal can produce wine and cloth more easily than England, England is still able to produce both cloth and wine, but it is relatively more difficult to produce wine in England than cloth: as any visitor to England will know, it lacks the regular sunshine needed to produce good grapes! From this example, we can see that a country has comparative advantage in those goods that it produces best as compared to how well it produces other goods. That is, Portugal is better at producing wine than cloth, and England is better is producing cloth than wine, even though Portugal is better than England at producing both goods. The Concept of Comparative Advantage using a modern example On Valentine’s Day the U.S. demand for roses is about 10 million roses. Growing roses in the U.S. in the winter is difficult. Heated greenhouses should be used. The costs for energy, capital, and labor are substantial. Resources for the production of roses could be used to produce other goods, say computers. Production possibilities for a given amount of resources in each country Roses (in millions) Computers (in thousands) U.S. 10 100 Mexico 10 30 Suppose that in U.S. 10 million roses can be produced with the same resources as 100 thousand computers. In Mexico 10 million roses can be produced with the same resources as 30 thousand computers. Note that resources used in making 10 million roses in U.S are not necessarily equal to the resources employed to make that many roses in Mexico. In this example Mexico is relatively less productive in computer production compared to U.S. Opportunity cost Note that the opportunity costs (the value of the next best option foregone) of production in the two countries are different. The opportunity cost of rose production is defined as the number of computers that must be given up to produce more roses. US Opportunity cost of producing 10 million roses 100 (in terms of thousands of computers not produced) Mexico 30 Here the opportunity cost of rose production is lower in Mexico has comparative advantage in rose production. U.S. has comparative advantage in computer production because the opportunity cost of computer production is lower in U.S. US Mexico Opportunity cost of 100 thousand computer 10 10*3.33 (in terms of millions of roses not produced) Benefits from Trade If each country specializes in the production of the good with lower opportunity costs, trade can be beneficial for both countries. Table 2-1: Hypothetical Changes in Production Roses (in millions) U.S. -10 Mexico +10 Total 0 Computers (in thousands) +100 - 10 + 70 The example in shows: If each country exports the goods in which it has comparative advantage (lower opportunity costs), then all countries can in principle gain from trade. Once every country specializes in production of goods that has a comparative advantage in, and then trades its excess supply, world production increases. The extra production is the result of better allocation of resources. This extra production can be divided between the trading countries allowing them to achieve higher consumption levels. Absolute Advantage versus Comparative Advantage If it takes the same amount of resources to produce 10 million roses in both countries then we say US has absolute advantage in computer production because it can produce more computers with the same resources or it takes less resources to produce computers in US than in Mexico. If it takes fewer resources to produce 10 million roses or 30 thousand computers in US then we say US has absolute advantage in both goods. However comparative advantage does not depend on absolute advantage. In the example above US has comparative advantage in computer production regardless of the amount of resources it uses for computer production (regardless of whether the resources used to produce 10 million roses in US is larger the same or less than that in Mexico). What determines comparative advantage? Why relative productivities are different in the two countries? This could be because of technological differences in the two countries and the quality of the resources and that of factors of production available to the two countries (i.e., fertile land and suitable weather in Agriculture, capital and skilled labor). A Ricarian like Example Consider two goods (say wine and cheese) produced using labor only and two countries (Home, Foreign *) The unit labor required (hours of labor) to produce one unit of output is represented with a for home and a* for the foreign country. Note that a=L/Q thus 1/a=Q/L or simply labor productivity A numerical illustration Unit Labor Requirement In Home one would have to give up 2 pounds of cheese to get 1 gallon of wine The OC of 1 gallon of wine is 2 pounds of cheese OC of W the amt of C you have to give up in order to have 1 gallon of W In Foreign give up 0.5 pound of cheese to get one gallon of wine The OC of 1 gallon of wine is 0.5 pound of cheese Opportunity Cost (before trade) Home Foreign Cheese (1 pound) 0.5 gallon of wine 2 gallons of wine Wine (1 gallon) 2 pound of cheese 0.5 pound of cheese A country has a comparative advantage in a good when it has a lower opportunity cost of producing than another country. Here Home has comparative advantage in cheese and Foreign in wine. Opportunity Cost (no trade) C in terms of W W in terms of C . In Home aLC /aLW = 0.5 gl W/lb C aLW /aLC = 2 In Foreign a*LC/a*LW = 2 a*LW /a*LC = 0.5 – Here Home has absolute advantage both goods because it takes fewer resources to produce wine and cheese in Home country (MPL is higher in Home): that is aLC < aLC* and aLW < aLW* (or MPLC > MPL*C and MPLW > MPL*W ) But absolute advantage is irrelevant to trade. In the example Home has comparative advantage in Cheese production because opportunity cost of Cheese production is lower (0.5< 2) that is aLC /aLW < aLC* /aLW* – – => MPLw/MPLc < MPLw*/MPLc* Home is relatively less productive in Wine production (Foreign is relatively more productive in Wine production) Home has a comparative advantage in cheese and will export it to Foreign in exchange for wine. Opportunity cost of Cheese in lower in Home = Cheese is relatively cheaper in Home = Home is relatively more productive in Cheese production = Home has comparative advantage in Cheese there is only one price ratio in each country o Op.cost W and C are just reciprocal of each other In Home: W in expensive and C is cheap In Foreign: C is expensive and W is cheap Now trade and make money sell one gallon of foreign W in US mkt in exchange for 2 pounds of US cheese and then sell each pound of US cheese for 2 gallons of foreign wine in foreign mkt and make 3 gallons of wine profit! All in all, this condition is rather confusing. Suffice it to say, that it is quite possible, indeed likely, that although Foreign may be less productive in producing both goods relative to Home, it will nonetheless have a comparative advantage in the production of one of the two goods. If Home is twice as productive in wine production relative to Foreign but three times as productive in Cheese, then Home's comparative advantage is in Cheese, the good in which its productivity advantage is greatest. Similarly, Foreign's comparative advantage good is wine, the good in which its productivity disadvantage is least. This implies that to benefit from specialization and free trade, Home should specialize and trade the good in which it is "most best" at producing, while Foreign should specialize and trade the good in which it is "least worse" at producing. The Formal Model Assumptions Consider two goods (say wine and cheese) produced using labor only and two countries (Home, Foreign *) Labor - homogeneous within every country • mobile domestically and immobile internationally. • supply of labor is fixed in each country. Technology: unites of labor required to produce one unit of a product. o The unit labor requirement is the number of hours of labor required to produce one unit of output. This is represented by a for home and a* for the foreign country. o Note that a=L/Q thus 1/a=Q/L or simply labor productivity Perfect competition prevails in all market • There are no other costs involved (transportation costs, etc.) This is a General Equilibrium Analysis: Now let us looking at the whole economy General Equilibrium v.s Partial Analysis o PE is a study of a mkt for a commodity in isolation Increase in Supply of C leads to a decrease in Price of C o GE incorporates impact on other goods (Wine) and “factors”, like L. Production Possibilities • The production possibility frontier (PPF) of an economy shows the maximum amount of a good (say wine) that can be produced for any given amount of another (say cheese), and vice versa. • The PPF of our economy is given by the following equation: aLCQC + aLWQW = L (1) Note that opportunity cost, reflected by the slope of PPF, is constant in each country and given by the ratio of ULR in the two sectors, that is aLC / aLW Relative prices before trade: Denote with PC the dollar price of cheese and with PW the dollar price of wine. Denote with WW the dollar wage in the wine industry and with WC the dollar wage in the cheese industry. – – – – Under perfect competition price of each good is equal to its marginal cost: i.e. PC = MCC MCC = WC aLC ,wage rate in Cheese industry x labor required to produce a unit of wine that is aLC So PC= WC aLC Thus WC =PC / aLC or (WC = PC . MPLC) That is the hourly wage in Cheese (Wine) industry is equal to the value of what a worker can produce in an hour. – If WC > WW that is if PC /aC >PW /aW or PC /PW > aC /aW then no Wine will be produced QW =0 and QC = L/aLC i.e, when the relative price of cheese (PC/PW) exceeds its opportunity cost (aLC / aLW), then the economy will specialize in the production of cheese. – If WC < WW that is if PC /aC <PW /aW or PC /PW < aC /aW then no Cheese will be produced QC =0 and QW = L/aLW – If WW = WC that is if PW /aW = PC /aC or PW /PC = aW /aC then both QC and QW will be produced In the absence of trade, both goods are produced, and therefore PC / PW = aLC/aLW. Or PC / PW = MPLw/MPLc – Home Equilibrium with No Trade From our previous example, we have aLC = 1, aLW = 2 and L=120 in Home country. Home: QW QC + 2QW = 120 Home aLC/aLW = 0.5 60 A U2 U1 L /aLC = 120/1= 120 QC In absence of trade consumption in every country is constrained to its production. Before trade Home country produces and consumes at point A where its production possibility frontier is tangent the highest social indifference curve in autarky U1. We will refer to point A as the “no-trade” or the “pre-trade” equilibrium for Home. We are assuming that there are many firms in each of the wine and cheese industries, so the firms act under perfect competition, i.e. taking the market prices for wine and cheese as given. The idea that perfectly competitive markets lead to the highest level of wellbeing for consumers – as illustrated by the highest level of utility at point A – is an example of the “invisible hand” that Adam Smith (1723-1790) wrote about in his famous book The Wealth of Nations. Like an “invisible hand,” competitive markets lead firms to produce the amount of goods that results in the highest level of well-being for consumers. Foreign Equilibrium with No Trade In Foreign country we have: a*LC = 6 , a*LW = 3 and L* = 300 so the production possibility frontier for foreign country is given by: Foreign : 6Q*C + 3Q*W = 300 2Q*C + Q*W = 100 Similarly the Foreign country produces and consumes at point a. Before trade prevailing prices in every country is equal its opportunity cost. Foreign QW L*/a*LW = 100/1= 100 P*C/P*W = a*LC/a*LW = 2 a U*1 50 QC Case Study: Us Comparative Advantage in Wheat Production The U.S. textile and apparel industry faces intense import competition, especially from Asia and Latin America. Employment in this industry in the United States fell from about 1.5 million people in 1990 to less than 1 million in 1999. One example of this import competition is the response of a U.S. fabric manufacturer, Burlington Industries, which announced in January 1999 that it would reduce its production capacity by 25% due to increased imports from Asia. Burlington closed seven plants and laid off 2,900 people, about 17% of its domestic force. After the layoffs, Burlington Industries employed 17,400 persons in the United States. With 1999 sales of $1.6 billion, this means that its sales per employee were $1.6 billion/17,400 = $92,000 per worker. This is exactly at the average for all U.S. apparel producers, as shown in Table 2.2. The textile industry is even more productive, with annual sales per employee of $140,000. In comparison, the average worker in China produces $13,500 of sales per year in the apparel industry, and $9,000 in the textile industry. Thus, a worker in the United States produces 7 times more apparel sales than a worker in China and 16 times more textile sales. If the United States clearly has an absolute advantage in both of these industries, why does it import so much of its textiles and apparel from Asia, including China? The answer can be seen by comparing the productivities of cloth and textiles to those in other industries, for example in the wheat industry. Table 2.2: Apparel, Textiles and Wheat in the U.S. and China United States Apparel Textile Wheat Apparel/(Wheat x 1000) Textile/(Wheat x 1000) Sale/Employees $92,000 $140,000 China Absolute Advantage Sale/Employees $13,500 U.S./ China Ratio 7 $9,000 16 Bushels/Hour Bushels/Hour U.S./ China Ratio 27.5 0.1 275 Comparative Advantage (opportunity cost of wheat) Bushels/$ Bushels/$ 92,000/27,500=3.34 13,500/100=135 140,000/27,500=5.1 9,000/100=90 or Comparative Advantage (Wheat/Apparel) x 1000 27,500/92,000=0.3 (Wheat/Textile) x 1000 27,500/140,000=0.2 Note: Data are for years around 1995. 100/13,500=0.01 100/9,000=0.01 The typical wheat farmer in California devotes only 1.35 hours per acre to growing a crop of wheat, and an acre provides 37 bushels of wheat. This works out a marginal product of 37/1.35 = 27.5 bushels per hour of labor. In comparison, the typical wheat farmer in China obtains only one-tenth of a bushel per hour of labor, so the U.S. farmer is 27.5/0.1 = 275 times more productive! The United States has an absolute advantage in all of these industries, but it clearly has the comparative advantage in wheat. Thus, it exports wheat to the China, while importing textiles and apparel, just as predicted by the Ricardian model. The Patterns of the International Trade Post-Trade Equilibrium If countries specialize according to their comparative advantage, they all gain from this specialization and trade. Since by assumption Home has CA in Cheese it will specialize in Cheese production and exports its excess supply of Cheese to the world market and purchases (imports) all the Wine it needs from the work market. Similarly Foreign country will specialize in Wine production. World price ratio will be something between the pre-trade domestic price ratio of the two countries Pc / Pw < (Pc / Pw) World < P*c / P*w Note that in Home before trade W=PC / aLC and W = PW /aLW. With trade PC↑ and PW↓. That increases wages in the Cheese and reduces them in the wine industry. Thus all the workers in Home move to Cheese. Home produces at point P and sells its Cheese in world market at (Pc / Pw) World. This allows Home to achieve consumption possibility frontier beyond its PPF. Recall the consumption possibility frontier states the maximum amount of consumption of a good a country can obtain for any given amount of the other commodity. With trade Home can consume at point C along PC where its post trade CPF is just tangent the highest social indifference curve. Foreign P QW 100 P QW 80 50 a U*2 U*1 25 50 80 C QC 35 0 60 P = (PC/PW)World U2 60 c 20 Home A U1 40 50 120 P QC Terms of Trade and Relative Wage Rates Demand determines terms of trade (TOT), TOT = PX /PI where PX = price of exports & PI = price of imports The relative wage is linearly related to the terms of trade TOT= PX /PI = PC /PW, for Home, where PC and PW, are world prices of C and W - Home makes Cheese only so w= Pc / aLC - Foreign makes Wine only so w* = Pw / aLW* W/W* = (Pc / aLC)/(Pw / aLW*) = (aLW* /aLC)(Pc / Pw)= (aLW* /aLC) TOT or W/W* = (MPLC / MPL*W) TOT - the higher the TOT the higher the home wages the higher the productivity in export industry (i.e., 1/aLC for home country) the higher the wage rate. Because there are technological differences between the two countries, trade in goods does not make the wages equal across the two countries. A country with absolute advantage in both goods will enjoy a higher wage after trade. Solving for Wages Across Countries Unit Labor Requirement Home produces and exports cheese, so we can think of Home workers being paid in terms of that good: their real wage is MPLC = 1 pound of cheese. We refer to this payment as a “real” wage because it is measured in terms of a good that workers consume and not in terms of money. The workers can then sell the cheese they earn on the world market at the relative price of (Pc / Pw) World = 1. Thus, their real wage in terms of units of wine is (Pc / Pw) WorldMPLC = (1) 1 = 1 gallons. the Home wage is: MPLC = 1 pound of cheese or (Pc / Pw) WorldMPLC = 1 gallons of wine (0.5 without trade) Foreign produces and exports wine, and the real wage is MPL*W = 1/3 gallons of wine. Because wine workers can sell the wine they earn for cheese on the world market at the price of 1, their real wage in terms of units of cheese is (Pw / Pc) WorldMPL*W = 1/3 pounds. Thus, the Foreign wage is (Pw / Pc) World MPL*W = 1/3 pound of cheese (0.167 without trade) or MPLW = 1/3 gallons of wine Foreign workers earn less than Home workers as measured by their ability to purchase either good. Predictions of the Ricardian Model: With free trade countries specialize (completely) in good(s) with lower opportunity cost of production (or relatively higher labor productivity), export excess production in those sectors and import the other goods. Free trade increases the national (and the individual) welfare (consumption, income or wage rates) in all trading countries. No one will be worse off. But we do not see extreme specialization in the real world There are three main reasons: 1. In reality MPL is not constant as assumed in the model. That makes PPF nonlinear. That is opportunity cost might be increasing. So a product with comparative advantage before trade may lose its comparative advantage as more of it is produced after trade. This is likely to happen when we have more than one factor of production. 2. Countries sometimes protect industries from foreign competition. 3. It is costly to transport goods and services. In some cases transportation is virtually impossible. Example: Services such as haircuts and auto repair cannot be traded internationally; introducing transport costs makes some goods nontraded. Empirical Evidence Can get an accurate prediction about actual international trade flows? McDougall study using early Post WWII period data 1951 Comparing British and American Productivity and Trade British Labor productivity was less than US in almost every sector (1/2US). America had absolute advantage in almost everything Yet the amt of British overall export was equal to that of US U.S. productivity exceeded British in all 26 sectors by margin of 11 to 366% US exports were larger than U.K exports only in industries where US productivity advantage was larger than twice as much U.S. exports goods in sector x if its cost of production is lower than UK: W aX < w* a*X or W/ W* < a*X / aX That is U.S. exports x if: W/ W* < (1 / aX) / (1 / a*X) = (MPLX/MPL*X) U.S.-UK relative wages < U.S-UK relative labor productivity in sector x Since U.S.-UK relative wages: W/ W* = 2 U.S. exports in sectors in which U.S-UK relative labor productivity > 2 And UK exports in sectors in which U.S-UK relative labor productivity < 2 Question: Why the most productive firm in the most productive country does not necessarily prevail in international competition? Answer: Because there might be firms (in other industries) with even a stronger productivity advantage driving market wages (cost of production) so high that the firm in question cannot compete internationally. Significance of Ricardian Assumptions Assumption of one homogeneous factor of production with constant MPL: o Makes everyone in society exactly the same in terms of skill & income. This masks the fact that there are losers and winners from trade within any country. o This assumption leads to the conclusion that country size doesn’t matter in international trade. Technological differences are exogenous o Technological differences are the main source of the difference in wages rates between countries. And trade does not change that fact in the Ricardian model. For higher wages a country must improve its technology. o The model assumes that there is no connection between technological change and trade. But trade can hinder or facilitate technological change. o If capital explains technological difference, for instance, then dynamic investment accumulation should be included in the model before evaluating the merits of trade. Labor is perfectly mobile between industries and perfectly immobile between countries: • There are actually large transition costs to specialization: 50 year old auto worker has grave difficulties in finding a job in another sector say IT. The model assumes he can and he will earn an income no less than the one he was earning on his previous job (he is as productive as any existing worker in the IT sector). The assumption masks the losses to import competing industries and its factors of production. Constant Returns to Scale • Double labor double outputs? • “Strategic” industries like airplane manufacture that face increasing returns to Scale (learning by doing) Conclusion and Summery Two surprising conclusions: A country may benefit from free trade even if it is less efficient than all other countries in every industry. It makes sense that one firm would be more successful than another firm in a local market if it could produce its output more efficiently, that is at lower cost, than the second firm. If the two firms produce identical products, then the less efficient firm is likely to be driven out of business, generating losses. If we extend this example to an international market then it would also make sense that a more efficient foreign firm would absorb business from a less efficient domestic firm. Finally, suppose all firms in all industries domestically were less efficient than all firms in all industries in the foreign countries. It would then seem logically impossible for any domestic firms to succeed in competition in the international market with the foreign firms. International competition would seemingly have only negative effects upon the less efficient domestic firms and the domestic country. A domestic firm may lose out in international competition even if it is the lowest cost producer in the world. This result is a corollary of the previous point. As argued there, it seems reasonable to think that a more efficient firm (i.e., one who produces at lower cost) would drive its less efficient competitors out of business. The same would seem to follow if the two firms are domestic and foreign and the two firms compete in international markets. However, the Ricardian model of comparative advantage argues that a firm in one country, even if it is the lowest cost producer in the world, may be forced out of business once the country liberalizes trade with the rest of the world. Even more surprising, despite the decline of this industry, the move to free trade can generate welfare improvements for everybody in the country. In other words, losing production in a highly efficient industry can be consistent with an improvement in welfare for everyone. This contradicts the logic above which would suggest that more efficient (lower cost) firms should always win. It is important to note that this result does not imply that every decline of an efficient industry will improve welfare. Instead, the model merely suggests that one should not jump to the conclusion that the loss of an efficient industry will have negative effects for the country as a whole.