Fallacies

advertisement

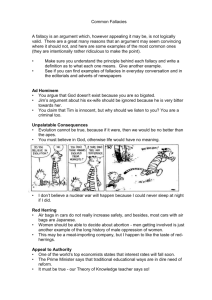

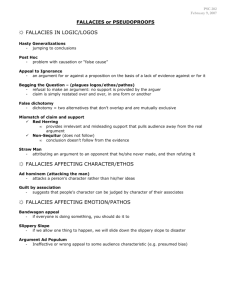

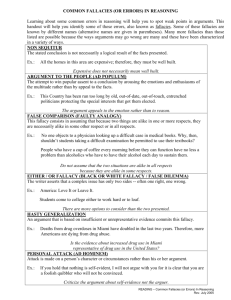

6 Fallacies People frequently employ bad arguments. Why is this? One important reason may be that arguments are more often used to persuade, rather than to find out what is actually a good belief or course of action. Indeed, given that we often have a personal interest in convincing other people of something, one might be tempted to think that some people use arguments which they know to be bad, but which they hope will nevertheless persuade the other person. Interestingly, this is rarely the case. Most of the time that people use bad arguments, it is because they themselves don’t know that they are bad arguments either. Instead, it seems that humans have developed several patterns of reasoning that are persuasive to most humans, but that are in fact not good arguments. We call such arguments (that look good, but are bad) fallacies. Philosophers have distinguished many different kinds of fallacies. The following sections contain some of the most widespread, and most persistent ones. 6.1 Fallacies: Fallacies of Relevance Remember that the two most basic criteria of a good argument are that the premises support the conclusion, and that the premises are plausible by themselves. Fallacies that violate the first criterion are called Fallacies of Relevance, as here the premises stated have no relevance on the truth of the conclusion. Appeals to Fear or Desire When it comes to the question of whether or not our existence has any kind of reason or meaning, many people say that it does have some kind of meaning, for else the world would seem awfully bleak and dark. However, such people substitute fear for reason. Yes, it may seem like a horrible thing if our lives would have no meaning, but you have thereby given no evidence or other reason to the contrary. In general, believing that something is not the case because you fear the implications of it being the case is invalid reasoning, and is called the fallacy of appeal to fear. Similarly, believing that something is the case because you desire its implications is invalid as well, and such reasoning commits the fallacy of appeal to desire. Appeals to Tradition or Popularity Often people will defend their belief or course of action by saying that people have always believed or acted that way. However, notice that someone who challenges this position, would simply challenge the tradition as well: maybe we have traditionally held a mistaken belief or course of action. So, an appeal to tradition does not give much reason to believe a certain claim. Very much related is the appeal to popularity, which says that we should believe something just because the majority of people believes it. Again, maybe all those people are wrong. Once again, the mistake is that no direct evidence or other reason is presented. Of course, there does seem to be something prudent about adopting a belief or action that so many other people have adopted as well: presumably, they had their reasons for doing so. But there’s the hitch: did they really have reasons for doing so, or were they themselves just following others? And were these reasons any good? Indeed, if other people did find good reasons for believing or doing something, then doing a bit of research and finding those very reasons would give us a good argument. For a good critical thinker, this should be no problem. Ought-From-Is Fallacy A fallacy very much related to the appeal to popularity or tradition, but often brought up in the context of ethics and morals, is the ought-from-is fallacy. This is we defend the morality or rightfulness of some act based on the fact that act is exactly as things are, or have been happening: “We ought to do X, because X is what we are doing now.”. Of course, if the reasoning is being laid out this explicitly, it is obviously a fallacy: Why would things we are doing be right, just because we are doing those things?! But, there are many much more subtle forms of this very fallacy, such as when we declare things or actions to be good because they are natural, normal, or common. Appeal to Authority Also related to the appeal to popularity or tradition is the appeal to authority. When we appeal to authority, we claim that we should believe something because some authority figure believes it. Now, appealing to authorities is a little better than appealing to popularity: if my physics professor or my physics textbook says that nothing can go faster than the speed of light, then we have a very prudent reason to believe this. However, problems remain the same as before: no direct reasons are given in this argument, and maybe even the authority figure got it from some other authority figure. Thus, while for practical reasons (shortage of time and energy) we sometimes have to rely on authorities to get anywhere, it is still always better to directly state the reasons that supposedly the authority would have in favor of the belief or action at hand. A further problem with appeals to authority is that sometimes such appeals can be completely inappropriate. For example, suppose we argue that nuclear weapons are bad, because Einstein said so. The problem here is that while Einstein was an expert on how nuclear weapons work in terms of their underlying physics, that does not necessarily make him an expert on the kinds of political and sociological issues that an issue like this requires. Indeed, authorities are not of all the same quality, authorities may be forced or have other incentives to say certain things, and sometimes authorities aren’t even identified, such as when we claim that some product’s power is ‘scientifically proven’. For all these reasons, critical thinkers should be skeptical of any appeal to authority. Appeal to Ignorance A particularly dangerous fallacy is the appeal to ignorance. In this fallacy, we claim that something is the case, because no one has shown that it is not the case. For example, someone may claim that God exists because no one has shown that God does not exist. However, when nothing has been shown, all we have is ignorance regarding that very issue, and nothing can be shown based on ignorance. Ad Hominem Sometimes, we try and refute someone’s argument by attacking the person, rather than the person’s argument. For example, if someone says that Bill Clinton’s reasons for increasing the funding for national health care are bad because Bill Clinton was involved in a sex scandal, then this person is saying something about Bill Clinton, rather than about Bill Clinton’s argument. Indeed, maybe Clinton’s reasons are good reasons. Ad hominems do not always have to say something negative about the person. Indeed, some of the most prevalent (and most persuasive) ad hominems are much more subtle. Consider the following argument: Of course he is opposed to rent control. He owns 6 apartment buildings himself! In this example, the speaker tries to argue that the apartment owner’s claim that rents should not be controlled should be rejected on the basis of the owner’s interests in that very claim being true. However, just because the owner has an interest in that claim being true, doesn’t make the claim not true: maybe the best course of action is to oppose rent control, which happens to be something that is in the interest of the owner. Rejecting someone’s claim on the basis of that person’s circumstances under which that person makes that claim is called a circumstantial ad hominem. Probably the most prevalent ad hominem is what is called the inconsistency ad hominem. In an inconsistency ad hominem, someone’s claim is rejected on the basis of that claim being inconsistent with something else that person believes, believed, does, or has done. For example, Rush Limbaugh once found Tom Cruise to be a hypocrite in urging people to do more in protecting the planet from garbage and pollution, when Tom Cruise often participates in movies with highly wasteful explosions and crashes. However, while Tom may indeed be hypocritical for this, it doesn’t mean that Tom is wrong in saying that we should be less wasteful, but it was of course the latter that Rush was after. 6.2 Fallacies: Fallacies of Assumption Fallacies that violate the second criterion of a good argument (the premises should be plausible), are classified as Fallacies of Assumption. Below are some common such fallacies. Straw Man A very common strategy to refute someone’s position is to distort this person’s position (usually by exaggeration of what that person is saying), after which reasons against the distorted position are being given. However, reasons against the distorted position do of course nothing to refute the original position. We say that the attacker is putting up a straw man: a distortion of someone’s real position, where the distortion is defenseless. Here is a good example from Rush Limbaugh: I’m a very controversial figure to the animal rights movement …. because I am constantly challenging their fundamental premise that animals are superior to human beings. Begging the Question and Circular Reasoning In a good argument, the premises should be less controversial than the conclusion. Thus, if I argue that God exists because the Bible says so, then I am assuming the equally controversial statement that everything that the Bible says is true. However, someone who doesn’t believe in God probably doesn’t believe everything that the Bible says either. Hence, this argument doesn’t work, and it is said to beg the question. In fact, if I argue that we should believe the Bible because it is the word of God, then I am in effect assuming that God exists. Hence, I would support God’s existence by indirectly assuming God’s existence! This special form of begging the question is called circular reasoning. False Dilemma Sometimes, people reason that if answer A isn’t right, then answer B must be the right one. However, this reasoning is only correct if A and B are the only two possible answers. If not, then the fallacy of false dilemma has been committed. Example: “The theory of evolution is mistaken, therefore creationism is true.” This argument is fallacious, because there can be other alternatives as well.