note case - Penn APALSA

Copyright Outline (Fall 2009) – Jennifer Tam

Introduction

I.

Copyright law in general a.

copyright is about property rights in expressive works i.

in rem rights rights that avail against the rest of the world ii.

cannot just go around giving people property rights, many people are immediately subject to them b.

what does copyright mean? i.

copyright law creates and protects rights in original works of authorship ii.

copyright is essentially a bundle of rights in literary, musical, choreographic, dramatic, and artistic works

1.

the rights are exclusive and avail against the rest of the world

2.

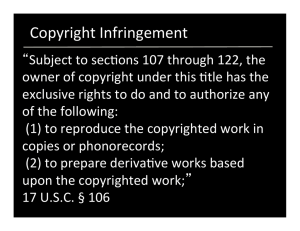

6 specific rights iii.

copyright law today encompasses most literary, artistic, and musical works, but also architectural works and computer software and some kinds of databases

1.

rights also expanded: derivative works rights, performance rights, and display rights the right to use (and to authorize the use of) the work iv.

copyright is a form of legal adaptation, a response to new technologies in the reproduction and distribution of human expression (and the social, cultural, and economic trends of those technologies) c.

federal copyright law i.

purpose: protects expressive, original works of authorship ii.

term: length of the author's life plus 70 years iii.

how to get a copyright

1.

copyright does not spring into existence as a result of an official decision, but originates in the creative act in an author a.

the work must be: i.

original (originates with the author)

I.

II.

not copied also implies creativity ii.

fixed in tangible medium of expression

I.

pretty flexible

2.

subsequent registration of a copyright with the Copyright Office enhances the value of an owner's right, but is not the source of it iv.

defending a copyright

1.

scope of right is very broad: 6 exclusive rights, moral rights (important in other countries)

2.

important exception for infringement is fair use

II.

Intellectual property law a.

in general, is comprised of 3 different branches i.

what they all have in common is that they protect rights in information ii.

subject matter is intangible, not physical

1.

creates boundary problems, definition problems

2.

not standard assets b.

the 3 branches of intellectual property law i.

patent law = limited "monopoly" for new and inventive products, process, and designs ii.

trademark law = prohibition on product imitators, to prevent passing off goods and services as products of others iii.

copyright law = protection of "original works of authorship" c.

federal patent law i.

purpose: protects innovative products, processes, compositions of matter, and product designs

1.

creates a limited monopoly in return for disclosure of the patentee's discovery ii.

term: generally 20 years from the date on which the application for the patent was filed

1.

14 years from issuance for design patents iii.

how to get a patent

1.

claimant's rights depend wholly on a government agent (the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office)

2.

need to apply with the U.S. Patent Office a.

undergo a review process b.

must specify what you're claiming (what you want to be protected) to the examiner c.

must explain what your contribution is, over the status quo of the prior art

1

3.

process is time-consuming and expensive a.

patents must be applied internationally, too iv.

types of patents

1.

utility patents a.

invention must be: i.

new (contrast to copyright, which only requires "original") ii.

useful (invention must work as described in the patent application and must confer some technological benefit upon humankind) iii.

non-obvious (examine scope and content of prior art, differences between prior art and claim, and level of ordinary skill of a worker in the discipline) iv.

a product or process

2.

plant patents a.

given for discovering and asexually reproducing new and distinct plant varieties

3.

design patents (only a 14 year term from grant date) a.

given for new, original, and ornamental designs for articles of manufacture v.

defending a patent

1.

can bar others from manufacturing, selling, and importing the patented invention

2.

very few defenses for the defendant

3.

the Patent Act allows for injunctions up to 3x damages for certain infringements

4.

appeals can be taken to the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit

5.

in litigation, the patentee runs the risk of having the patent invalidated, even after incurring the expense of obtaining the patent d.

federal trademark law i.

purpose: protects symbolic information that signifies the origin of goods and services

1.

essence of a trademark right is in use of the mark

2.

a mark can be a word, symbol, or device used as a brand for a product or service, so long as it is used by a business to distinguish its goods or services from those of others a.

a proxy for a company's goodwill b.

began as a branch of consumer protection law, to prevent consumer confusion i.

originates in common law c.

has changed now – identifying marks themselves have become extremely valuable i.

Google's trademark is worth $66 billion ii.

term: infinite

1.

can be abandoned by non-use or can fall to public domain if it no longer distinguishes the goods or services (ex: aspirin, trademark name becomes the generic name of the product) a.

generic if it no longer distinguishes the brand from the product or process (as opposed to distinguishing the brands from each other) iii.

how to get a trademark

1.

the right springs directly from the claimant's qualifying use of a mark on a product, with or without later confirmation of an official registration a.

the substantive right to preclude others from using the mark vests only when the use has been demonstrated

2.

can file with Trademark Office, too a.

can register it before using it, too, but must use it within a few years b.

the Lanham Act established registration system for trademarks and confers procedural advantage in litigation to registered trademarks c.

is optional, but get more advantages i.

constitutes constructive notice to the rest of the world ii.

evidences ownership iii.

can help to establish priority in other countries

I.

help show "first in time" iv.

invokes federal jurisdiction over trademark, puts you in federal court

3.

trademark must be: a.

non-deceptive b.

not confusingly similar to another mark c.

not merely descriptive of the goods or deceptively mis-descriptive of them iv.

defending a trademark

2

1.

get exclusive right to use the mark in connection to your products and services, and right to bar others from using an identical mark or a similarly confusing mark in connection with their product and service

2.

trademark is infringed when a 3 rd party, without authorization, uses a confusingly similar mark on similar goods or services a.

test is whether the concurrent use of the 2 marks would likely cause consumers to be mistaken or confused about the source of origin or sponsorship b.

a lot of litigation about what is confusingly similar

3.

generally, the parties must be competition a.

in 1995, Congress passed a provision adding protection for "famous" marks against dilution, which doesn't require competition b.

only injunctive relief is available, unless the wrongful use was willful e.

state intellectual property law i.

unfair competition laws (complement to federal trademark law)

1.

provide a cause of action when one company passes off its goods or services, or itself, as something or someone else

2.

protects businesses from wrongful, unethical, or deceptive business practices adopted by competitors a.

torts-based body of law

3.

evoked a lot in trademark infringement suits a.

often go together ii.

trade secrets laws (complement to federal patent law)

1.

protect commercially valuable information that is not widely known to the public and whose holder adopted reasonable measures to maintain its secrecy a.

most famous example is the Coca-cola formula i.

instead of patenting it, they use trade secret protection

2.

covers broader subject matter than patents a.

extends to customer lists, marketing plans/strategies, know-how, and other info b.

any formula, pattern, device, or compilation of information which is used in one's business, which gives that person an opportunity to obtain an advantage over competitors who do not know or use it

3.

does not necessarily imply exclusive rights, though a.

>1 person knowing it does not disqualify it as a trade secret, as long as not public

4.

another difference from patent is that it does not require disclosure a.

that's what patent is all about – exchange of disclosure for a temporary monopoly b.

trade secrets are the mirror opposite i.

protection exists as long as it is not public

5.

trade secret term is for however long the secret lasts a.

infinite in principle

6.

trade secrets have the attributes of property, and can be licensed, taxed, and inherited

7.

can only be enforced against improper appropriation (theft or breach of contract) a.

often said to protect a relationship than a property interest iii.

common law copyright

1.

now almost entirely preempted by federal law a.

note that under the 1909 Copyright act, unpublished works were given protection under state common law copyright

2.

the 1976 Copyright Act now protects works as of their creation a.

§ 301, establishes its preemption b.

states can no longer regulate any topic that has been addressed by the federal

Copyright Act

3.

still has some power a.

state copyright law may be invoked, still, in reference to works of expression that have not been fixed i.

ex: improvisations, extemporaneous speeches that haven't been recorded b.

but not nearly as important as it used to be iv.

right of publicity

1.

an intangible right recognized by the courts in 1953

2.

the right to enjoy the economic value associated with a celebrity's name, likeness, image, voice, or any other evocation of the celebrity's traits

3

a.

right that celebrities have

3.

prohibits appropriation of the plaintiff's name or likeness for commercial benefit a.

harm occurs because the celebrity has been deprived of a property right in the fruit of her labors – the ability to exploit her name or likeness commercially

4.

more an absolute right than trademark or unfair competition rights based on theory of unjust enrichment

5.

action only requires theft of good will by the defendant's unauthorized use of the plaintiff's name or likeness

6.

continues to develop and grow as an area of law v.

misappropriation (the big umbrella)

1.

the broadest and vaguest doctrine under state law

2.

traces back to INS v. AP, 248 U.S. 215 (1918), in which "hot news" stories from the AP service were beat to publication by INS a.

activities deemed to be a new variety of unfair competition called "misappropriation" b.

created a quasi-property right in the news i.

a right that avails only against some people ii.

the public is free to discuss news, but competitors do not have the same rights

3.

something can still be invoked in both state and federal court a.

any type of IP case b.

the more recent history of the doctrine in courts is mixed

4.

most likely cases when: a.

1) the plaintiff, by substantial investment, has created a valuable intangible not protected by patent, trademark, copyright, or breach of confidence laws b.

2) the intangible is appropriated by the defendant, a free rider, at little cost c.

3) the plaintiff is injured and jeopardized in continued production of the intangible f.

international copyright i.

there has never been a "universal" copyright system

1.

instead, the author who wishes to protect his work abroad must typically look to the pertinent national laws of the countries where production is sought

2.

these national laws, in turn, are stitched together by a series of international agreements prescribing the conditions under which countries must give recognition under their domestic laws to works of foreign origin

3.

"formal reciprocity" of protection: that works originating in a signatory state would be assimilated, for purposes of domestic law, to those created by nationals of another signatory ii.

the Berne Convention

1.

the oldest and preeminent multinational copyright treaty

2.

campaign in the 1850s to establish world-wide recognition that copyright is a natural and indefeasible right which arises in the first instance (without state intervention) from the very act of "authorship" itself

3.

created the 1886 Act of the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works

4.

but it did not create a universal law of copyright

5.

premised on principle of "national treatment"

6.

evolved over more than a century, and has greatly improved the level of protection for copyright worldwide a.

established an international copyright regime which is truly multilateral (rather than bilateral or regional) i.

Convention "minima" supplement the principle of national treatment by setting a "floor" below which signatory countries may not go in extending protection to qualifying foreign works iii.

in 1891, the "Chace Act" was an amendment to U.S. copyright law, allowing the President to extend protection, by proclamation, to works originating in particular foreign countries (in return for those countries' protection of U.S. authors) iv.

the Paris Act of 1971 = current text of the treaty, to which the U.S. has adhered

1.

administered by the World Intellectual Property Organization ("WIPO") a.

intergovernmental organization with headquarters in Geneva

2.

subject matter: every production in the literary and artistic domain, whatever mode or form

3.

basis: must be given to published or unpublished works of an author who is a national of a member state

4

4.

preclusion of formalities: requires protection in foreign countries without any administrative formalities

5.

minimum term of protect: life plus 50 years, or 50 years from publication for cinematographic works and anonymous works

6.

exclusive rights granted are similar to those in § 106 of the 1976 U.S. Copyright Act

7.

have fair use exception

8.

enforcement: Article 33(1) provides for the submission of disputes among member states to the jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice in the Hague a.

usually don't take it there, so it ends up being policed by the member countries' domestic laws v.

in 1988, the Berne Convention Implementation Act passed in the U.S.

1.

the 1976 Act eliminated many of the impediments to Berne administration from earlier

Background

I.

History of copyright a.

began with the printing press i.

allowed works to become more easily reproducible ii.

makes expressive works more valuable, easily disseminated and sold

1.

but then other people could copy and sell the work, too b.

in 1557, in response, the Crown passed an act i.

feared the dissemination of materials against the church and crown ii.

gave a monopoly to the Stationare's (?) Company to print and copy works c.

in 1694, the monopoly expired i.

the Company lobbied for the extension of the monopoly ii.

the Crown didn't listen d.

in 1710, have the first copyright law in the Western tradition, the Statute of Anne i.

the Statute of Anne in 1710, the first English copyright act

1.

subject matter only concerned printed books

2.

amounted to the exclusive right to print and publish it ii.

the trigger to get protection was publication iii.

the list of exclusive rights primarily contained the right to make copies iv.

duration of 14 years

1.

could add another 14 year term if the author was still alive e.

in 1790, in response to the Copyright Clause, the first Copyright Act is passed i.

Constitution gave Congress power to promote progress of science and the useful arts by securing, for limited times, to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries ii.

the protected areas included maps, charts, and books iii.

the trigger to get protection was publication

1.

subsequently two other methods were added: a.

registration b.

deposit (in the Library of Congress) iv.

the exclusive rights included the right to print, reprint, publish and vend v.

duration of 14 years (plus 14 years again) f.

in 1901, major revision to the Copyright Act i.

significant expansion to the subject matter (all works of an author) ii.

triggers were notice (publication), registration, and deposite iii.

exclusive rights added adapt, translate, deliver, read and present, perform iv.

protection term was doubled to 28 years (plus 28 years) g.

brings us to the current state of things – the 1976 Copyright Act i.

subject matter becomes open list that includes:

1.

literary works

2.

musical works

3.

dramatic works

4.

graphic or sculptural works

5.

motion pictures and audiovisual works

6.

sound recordings

7.

architectural designs ii.

the triggers required are:

5

1.

fixation

2.

note that: a.

registration and deposit now optional b.

no need for publication or notice iii.

original term was life plus 50 years, but was amended h.

in 1998, the 1976 Act was amended i.

the term is amended to life plus 70 years ii.

enactment of Digital Millennium Copyright Act as an amendment

1.

§ 1201 of the DMCA a.

ban on circumvention of technological protection measures employed by content owners

2.

§ 512 of the DMCA a.

liability of internet service providers (ISPs) imposed b.

but created a safe harbor for a compromise i.

protected ISPs from damages if they comply with conditions listed in the statute i.

copyright protection has expanded in all dimensions i.

subject matter, triggers (more minimal, less prerequisites, easier to gain protection), exclusive rights, terms (getting longer) ii.

sources of expansion

1.

more interest groups have stakes in its development

2.

technology is expanding a.

more ways to spread information, need more ways to protect authorship

II.

Theories behind copyright a.

utilitarian conception (incentive theory) i.

strongly linked with the language in the Constitution's Copyright Clause, and remains dominant in

American judicial opinions

1.

says its purpose is to promote creative works a.

not really focusing on the authors per se

2.

a means ends structure

3.

want to encourage the science and arts because it's good for society

4.

focus on reaching a certain desirable result for society at large, instead of the author ii.

premised implicitly on economic reasoning

1.

starts with concept of public goods (in the economic sense) a.

have two characteristics i.

non-rivalrous consumption

1.

note that this characteristic does not exist for intangible/info goods a.

anyone can use the good, infinitely ii.

non-excludability of benefits (very difficult or expensive to prevent free riders from enjoying the good)

1.

ex: national defense can be enjoyed by anyone in the country, even if they do not pay their taxes iii.

if works of the mind are brought to the market, because they are intangible, they become a public good

so the author gets an insufficient return and will not be incentivized to create

1.

underproduction problem

2.

original authors bear the costs of creation and production (their time, resources, labor, etc.)

3.

copiers do not have to incur those costs a.

can charge a lot less (or nothing) b.

huge cost advantage, supplemented by informational advantage (can see how popular the work will be, how much the demand is) i.

already know the Mann curve when they operate

4.

authors will never be able to recoup their initial investment in the creation of the work because the copiers' copies will drive the value of the work down to nothing

5.

so the authors will just not write the book – not worth it iv.

the solution is to provide special incentives for the desired activity – copyright law

1.

solve the "public good" problem by recognizing a property right in the work, but the exercise of that monopoly is carefully circumscribed through regulation a.

tries to give authors a period of exclusivity, so that they will have opportunity to profit from their work

6

b.

formal recognition of property rights to create incentive for authors to produce expressive works c.

society will suffer without this protection, since fewer works will be made

2.

but balance ideas like originality, idea/expression dichotomy, and fair use since the copyright monopoly is limited in time v.

criticisms of this theory

1.

there are other inherent incentives in making a creative work a.

people want fame, recognition, respect b.

human beings like to do creative things just to do them (enjoyment), creativity is embedded in humanity i.

hardwired to be creative (per Lessig, Benkler) ii.

ex: YouTube, blogs c.

people like to contribute to community (altruism) d.

works are sometimes criterion of job, advancement, etc.

2.

there are some works that might not help society (no value) or might hurt it (negative value) vi.

most influential theory in U.S. copyright law b.

natural law conception (Locke's labor theory) i.

natural rights or inherent entitlement ii.

just as old as the utilitarian view, but is not as prominent in the U.S. (but in other countries) iii.

premised on the idea that individual who has created a piece of music/art should have the right to control its use and be compensated for its sale

1.

like a farmer is paid for his crops

2.

the author has enriched society with his contribution, so he has a fundamental right to obtain a reward commensurate with its value iv.

trying to figure out how resources move from the commons to private property v.

explaining the acquisition process

1.

1) ownership over one's body (at the very minimum we own our bodies)

2.

2) ownership of one's labor a.

labor is produced by our bodies

3.

3) by mixing labor with unowned/common resources, one establishes private property in the resources vi.

he put some limitations on his theory

1.

cannot commit waste

2.

must leave as much and as good for others a.

the second limitation shows that he didn't really think it through – no physical resources can be consumed without reducing consumption opportunities for others vii.

application to copyright theory

1.

can say that we are surrounded by a universe of expressive building blocks (notes, colors, shapes, letters)

2.

mix the author's own mental labor and physical labor with those blocks, then creates a property right in the resulting expressive work

3.

what about Locke's limitations? a.

don't really take anything away when create an expressive work b.

independent creations (even if they create identical works) are allowed under copyright laws c.

limited in time, so returns to the commons eventually viii.

problems of application of labor theory in modern law

1.

we don't use labor as the keystone of the law (no investment of labor required) a.

photography doesn't require much labor b.

case: Feist Publications v. Rural Telephone i.

if all you did was invest a lot labor but lack a measure of creativity, you will not get any protection ii.

even though there no question that you put a lot of effort into the process

2.

multiple authors can participate in a creative process, but very few will receive property rights in the final product

3.

fits pretty well, but there are some places where it doesn't quite work ix.

does appeal to our sense of fairness

1.

that labor and time spent deserves reward and ownership c.

Hegel's personality theory

7

i.

extension of Locke is Hegel's Personality Model

1.

trying to protect "moral" rights – the author's rights of "integrity" and "attribution"

2.

protecting the works as an extension of the author's personality ii.

started with physical property, but extended those theories to copyright iii.

believed that external objects are essential for the constitution of the self iv.

the key element is the human will and personality

1.

property is essential for the constitution of the self or for human flourishing

2.

express or present yourself to the rest of the world

3.

note Hegel was actually very against slavery, because cannot own people with their own personalities v.

societal recognition is important to the process of self-actualization legal protection represents society's stamp-of-approval and recognition of the self vi.

application to copyright theory

1.

perhaps expressive works embody to a greater extent the personality of the author

2.

should distribute more copies so that more people will know about you and you will flourish

3.

the linkage between the author and the work should never be severed

4.

touchstone here is originality, which is consonant with the law a.

moral rights are also consistent vii.

problems of application of personality theory in modern law

1.

multiple authors mean there are multiple personalities reflected in the work, and how should the rights in the work be allocated?

2.

copyright nowadays protect functional work (ex: software) that do not necessarily incorporate the author's personality a.

their creation is guided by function b.

might be able to argue that even in software that the personality can come through

3.

the right also ends at some point, severing the connection between author and work (but they are also dead at that point) viii.

this theory is very influential

1.

courts do believe that there is something unique about each author which qualifies them for copyright protection d.

Netanel's democratic paradigm i.

two purposes for copyright law

1.

productive function a.

imports the incentive theory's arguments b.

this is just phase one, though

2.

structural function a.

is more important b.

copyright law guarantees democratic rule c.

the key is not the number of expressive works, or whether they are high or low quality, but what is really important is enabling and supporting an independent, creative sector that need not rely on the good graces of the government d.

can provide the citizenry with constant informational and artistic feed that is necessary to maintain a democratic society e.

other rhetorics i.

rhetoric of misappropriation

1.

appeals to "fairness"

2.

one person cannot profit unfairly from the intellectual labor of another ii.

rhetoric of the public domain

1.

promotion the limitation on copyright

2.

arguing the limit on copyright is part of the constitutional scheme

3.

robust, open market is a good in its own right

4.

the non-property-ness of some information can promote various good social and cultural ends iii.

new economic rhetoric

1.

copyright is necessary to prevent free rides from undermining the market in creative expression, notwithstanding a concern for copyright's "social cost"

2.

copyright is a mechanism for market facilitation – moving creative works to their highest socially valued uses iv.

rhetoric of social dialogue and democratic discourse

1.

perceives a nexus between "social dialogue" and the creative process

8

2.

must reinforce the elaboration of new communications technologies

3.

promoting openness, freedom, and diversity of expression v.

rhetoric of "deference"

1.

judicial deference – in the way the law has been previously developed and interpreted

Prerequisites of Copyright Protection

I.

Requirements of copyright protection a.

the Copyright Act of 1976 establishes fundamental prerequisites for copyright protection i.

originality ii.

fixation iii.

a modicum of creativity (implied) b.

1976 Act, § 102(a): i.

"Copyright protection subsists . . . in the original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression, now known or later developed, from which they can be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated, either directly or with the aid of a machine or device."

Fixation

I.

Fixation, generally a.

a work is incapable of protection under federal law unless it is "fixed" in a "tangible medium of expression" i.

the medium can be one "now known" or "later developed"

1.

phonorecords are the embodiment of musical works

2.

copies are embodiments of all other works ii.

fixation is sufficient if the work "can be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated, either directly or with the aid of a machine or device" b.

fixation is important on two different dimensions i.

copyrightability ii.

infringement

1.

one of the exclusive rights of the author is to control the making of copies

2.

if someone makes an unauthorized copy of the work, then they have infringed a.

they "fixed" without permission

II.

Source of fixation requirement a.

originates from the Copyright Clause of the Constitution i.

allows Congress to make laws to protect the "Writings" of authors ii.

evidentiary reasons

1.

certainty to actors

2.

reduces adjudication costs to fact finders

3.

ensures that there are claims for things that can actually be copied or stolen iii.

gives notice to the rest of the world iv.

adds value by allowing more people to access and consume the work v.

creates markets for the copyrighted works

1.

better to be traded, need some physical embodiment of the good b.

fixation's qualities i.

durable, long-lasting ii.

the law gives 3 requirements

1.

embodiment in a physical object a.

originally, performances and speeches were not copyrightable but Act was later amended in 1989 to prohibit bootlegging, without fixation by author b.

Title 17, § 1101 prohibits the practice of bootlegging i.

not fixed, has no authority under the Copyright Clause of the Constitution ii.

is under the Commerce Clause power (only for recordings that move through commerce) – U.S. v. Martignon (2d. Cir. 2007)

2.

authorization (by or under the authority of the author) a.

ex: student can't copyright his notes if the professor forbids note-taking

3.

sufficiently permanent to allow the work to be perceived, reproduced, or communicated, directly or indirectly, with the aid of a machine, for a period of more than a transitory duration a.

the "with the aid of a machine" language was a result of White-Smith Music

9

III.

The fixation floor not transient a.

note the House Report on this Act says that transient images do not satisfy fixation b.

there is supposed to be a floor on fixation c.

MAI Systems Corp. held that turning on a computer counted as fixation! Congress responded i.

passed the Computer Maintenance Assuring Act (1998) ii.

became § 117(c) of the Copyright Act iii.

exempts service shops from copyright infringement if

1.

the copy is made solely by virtue of activating the computer,

2.

copy isn't being used for any other purpose and is destroyed, and

3.

service doesn't activate any software unnecessary for performance of the service iv.

saved the industry for computer repair v.

but MAI is still important because it set the fixation bar really, really low

1.

for infringement analysis, at least

2.

affects scope of protection d.

despite MAI, the fixation standard for copyrightability purposes should still be higher? i.

have different policy considerations in each analysis ii.

copyrightability is about requirements for gaining protection

1.

might want to make it more difficult to obtain protection

2.

cost to society, etc.

3.

but once you have it, probably want a wide scope of protection power e.

state law protections for unpublished works (unfixed) i.

California

1.

protects unfixed works

2.

amended its literary property state law

3.

Cal Civ. Code § 980(a)(1), 2003 ii.

New York

1.

done through their case law

2.

Hemingway v. Random House

IV.

Related cases a.

Goldstein v. California (note case – "writings") i.

412 U.S. 546 (1973) ii.

Supreme Court held "Writings" to mean any "physical rendering" of the fruits of the author's creativity b.

White-Smith Music Publishing Co. v. Apollo Co. (note case – piano rolls) i.

209 U.S. 1 (1908)

reflects an early reluctance to deal with copyright cases involving new modes of information storage.

The

1976 Act aimed to correct this tendency by exploiting more fully the potential of the “Writings” requirement. This case predates, and was partially overruled by the 1909 Act, and that didn’t deal with protectability even when it was good law. The reason is that, although the OUTCOME of the case was overruled by the 1909 Act, its WAY OF THINKING survived until the 1976 Act was passed, and even beyond. This case is an example of the “artificial and largely unjustifiable distinctions” that the fixation requirement in the 1976 Act was intended to avoid. ii.

iii.

this way of thinking lasted until the 1976 Act was passed iv.

dispute about the player piano's perforated rolls that would let the piano automatically play the songs written by the appellant (assignee of Adam Geibel, a composer) v.

opinion affirming the Circuit Court

1.

in considering the act, it seemed "evident that Congress has dealt with the tangible thing, a copy of which is required to be filed with the Librarian of Congress"

2.

in a broad sense a mechanical instrument which produces a tune copies it, but this is a strained and artificial meaning a.

not a copy which appeals to the eye

3.

not susceptible to being copied until it has been put in a form which others can see and read a.

perforated rolls cannot be read, even by those who make them b.

they do produce the same musical tones, but they are not copies within the meaning of the copyright act vi.

class notes

1.

defense argues that the perforated rolls are not writings because they are not intelligible to people, not readable

2.

the Supreme Court agreed because it's not a writing or copy, so no infringement

10

3.

Copyright Act was amended after

4.

case was overturned, and this case would be an infringement today c.

Midway Manuft'g Co. v. Artic Int'l, Inc. (PacMan and PuckMan)

Citation

Facts

Issue

History and

Precedent

Court's

Ruling

Class Notes

Midway Manufacturing Co. v. Artic International, Inc.

547 F. Supp. 999, aff'd. 704 F.2d 1009 (7 th Cir. 1982)

Midway produces video arcade games, including Galaxian and Pac-Man

the games run via computer programs on ROMs, processed by a CPU, to display images on the game screen

Midway brought suit, alleging that Artic sells two video devices which violate its rights in the Galaxian and Pac-Man games

1. Whether video game images constantly being recreated by a ROM program can be considered "fixed" as to be protected by copyright.

Copyright Act, 17 U.S.C. § 102(a) o the work must be "fixed in any tangible medium of expression, now known or later developed, from which [it] can be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated, either directly or with the aid of a machine or device"

Copyright Act, 17 U.S.C. § 101 o meaning of fixed o "sufficiently permanent or stable to permit it to be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated for a period of more than transitory duration"

Judge Decker, in favor of Π

Fixation requirement does not require that the work be written down or recorded somewhere exactly as it is perceived by the human eye.

plaintiff has successfully demonstrated all elements necessary for issuing a preliminary injunction are present in this case, and is granted

while Artic's argument has a certain facial validity, it nonetheless fails

"purely evanescent or transient reproductions" referred to by Congress referred to those arising from live telecasts or performances that are nowhere separately record

the technology involved is different from that of videotape, but Congress has allowed for it (later developed medium of expression)

the defendant, Artic, is arguing there is not adequate fixation here o the computer images on the ROMs are not fixed, they're constantly being regenerated by the computer o the skill level of the player affects the progression of the game

doesn't matter, the court says o there is enough repetition of the images and content that it counts as being fixed o the key/central elements are stored on the ROMs and that is good enough o not everything needs to be stored

this decision really helped this new developing industry

-

This case explores some of the ambiguities that surround the concept of fixation under the statute.

d.

MAI Systems Corp. v. Peak Computer, Inc. (note case – turning on computer) i.

991 F.2d 511 (9 th Cir. 1993) ii.

MAI is alleging that Peak is liable for copyright infringement for turning on the computer when they fix them (the copy of a program is fixed when the computer is turned on)

1.

alleged that a copy of the software was being transferred from the storage device onto the computer CPU by turning it on

2.

the copy disappears the moment the computer is turned off iii.

the 9 th Circuit found that the temporary copy was good enough for fixation

1.

sufficiently permanent to be perceived by users and is therefore copyright infringement iv.

fixation is coming up in the context of infringement

11

1.

in contrast to Midway, this is an infringement case, not a copyright case (it's already known that the software has a copyright) v.

Parchomovsky: this is a terrible decision

1.

MAI gets a monopoly over the services (servicing of the computers) e.

Hemingway v. Random House (note case - speeches) i.

244 N.E.2d 250 (N.Y. 1968) ii.

oral works or utterances may be protected if:

1.

1) speaker shows clear intention to attain protection

2.

2) speaker must clearly mark off parts intended to be protected iii.

Parchomovsky: do we really need it?

1.

has a chilling effect on speeches

2.

the fixation standard is already so low

3.

can't do it case by case, have to do it categorically – cost of doing this seems to outweigh benefit

4.

it's easy to just write it down

Originality

I.

Originality, generally a.

requires two factors i.

independent creation by the author ii.

a modicum of creativity

1.

most people don't list this as separate requirement b.

very low creativity standard i.

if make it higher, maybe would be excluding things that people would consider art and creative ii.

otherwise would be interjecting some subjective judgment of what is creative iii.

would make the process unbelievably time-consuming to judge every copyright request iv.

better to let everything in – let every work be copyrighted when created, remember

1.

we screen ex-post instead with infringement cases v.

"useful arts" requirement

1.

also does not establish any effective bar (see Bleistein) c.

what likely will fail for creativity i.

fragmentary words and phrases ii.

short slogans iii.

slight variations on musical compositions or stand up routines iv.

alternations of business forms

II.

Originality is not a shield a.

only is relevant for copyrightability, not infringement b.

in the copyright context, you may have enough originality to get protection, but it does not immunize you from infringement suits c.

a good defense is independent creation

III.

Photographs a.

photos of the exact same thing i.

each have their own individual copyright? even of the same thing? ii.

in older law, only artistic photos were entitled protection

1.

later dropped iii.

another rule was that you could not copy the copy (the photograph), but you can recreate the original

1.

re-enact the scene, not infringing in that case

2.

this long-standing principle still applies to large, immovable objects

3.

but when it comes to staged photos like in Sarony and Mannion, the rule changes and it's highly doubtful that it applies

IV.

Related cases a.

Atari Games Corp. v. Oman (note case – Breakout game) i.

888 F.2d 878 (D.C. Cir. 1989) ii.

produced a game called Breakout iii.

said there is nothing creative about this game – all these individual components are well-known

1.

not original enough iv.

the court rules for Atari

1.

the components of a game should be viewed as a whole

2.

the Copyright Office erred by focusing on the individual components on a standalone basis

12

3.

that's not how the originality analysis should be viewed

4.

even simple shapes, when combined in a distinctive manner, can be original selection and arrangement, combination of elements can be enough to get protection b.

Acuff-Rose Music, Inc. v. Jostens, Inc. (note case – "got to stand for something") i.

155 F.3d 140 (2d Cir. 1998) ii.

attempted to claim a copyright on the phrase "you've got to stand for something or you will fall for anything" iii.

so John Cougar Mellancamp used a slight variation of this phrase iv.

because of the widespread use of the phrase, the plaintiff failed to prove that he originated the phrase v.

Parchomovsky: this is a good decision, need to have some screening for such cases

1.

if you have a copyright, you get a license to sue others

2.

ex-post screening is a good thing

3.

he'd be able to sue everyone who said that phrase c.

Burrow-Giles Lithographing Co. v. Sarony (Oscar Wilde photo)

Citation

Facts

Issue

History and

Precedent

Court's

Ruling

Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony

111 U.S. 53 (1884)

Sarony is a photographer, with a large business in New York, who took a portrait of Oscar Wilde o he took the steps necessary to obtain copyright of the photograph

the lithographic company made and sold copies of the photograph

Sarony brought suit, claiming copyright violation

1.

Whether photographic works are copyrightable, despite the fact that the subjects of the photos are pre-existing and that the machine does the rendering.

the Copyright Clause of the Constitution

Class Notes

Justice Miller, in favor of Π

The Constitution is broad enough to cover authorizing the copyright of photographs, so far as they are representatives of original intellectual conceptions of the author.

judgment of the circuit court is affirmed

the first Congress of the United States amended the copyright statute to include maps and charts o these men were contemporaries of the Constitution, so their amendment should be given great weight o did not seem to matter that the maps and charts represented real things – if photography had been an art then, it would have been included, too

this work is the plaintiff's intellectual invention – arranging and disposing light and shade, suggestion and evoking the desired expression, arrangement of the setting, etc.

the court in the original trial found in favor of the plaintiff

the defense argues o a photograph is a mechanical reproduction of a subject/person/object that already exists in the real world o two arguments stemming from this

1) is not a "writing" under the Constitution

2) fails authorship requirement

the court's response o 1) is a "writing"

the revised statute includes maps and charts – which are also portrayals of real things

Congress always deemed that maps would be protected, and if those are, so are photographs

probably the only reason they weren't is because the technology hadn't been developed yet o 2) a photographer can be an author

in the composition and arrangement of a photograph,

13

there is human authorship

being a photograph does not disqualify it, can be an original work of art

decision seems to resonate well with the personality theory o discusses the mental conception of the photographer o the unique character of the photographer – his personality o Sarony saw something in his mind's eye, made it into a photo

also seems to agree with labor theory o Sarony worked to make the photograph d.

Mannion v. Coors Brewing (note case – athlete billboard) i.

377 F. Supp. 2d 444 (S.D.N.Y. 2005) ii.

protected elements include:

1.

composition of elements in the photo

2.

camera angle

3.

posing of subject

4.

lighting iii.

did not copy the photo, but copied the same setting with a different human model iv.

the court found infringement with their photos (p. 110) of the plaintiff's work

1.

when it comes to staged photographs, the breadth of the protection is greater e.

Bleistein v. Donaldson Lithographic Co. (circus ad)

Citation

Facts

Issue

History and

Precedent

Court's

Ruling

Concurrence or Dissent

Bleistein v. Donaldson Lithographic Co.

188 U.S. 239 (1902)

the defendant copied in reduced form three chromolithographs prepared by the employees of Donaldson Lithographic

the lithographs were advertisements for a circus, and depicted drawings of various acts being performed at the circus

the company brought suit for copyright infringement

1.

Whether advertisements (or little value illustrations) qualify for copyright protection.

Burrow-Giles Lithographing Co. v. Sarony o constitutional protection does not limit the useful to that which satisfies immediate bodily needs o also not affected by the fact that, if it be one, that the picture represents actual things

Justice Holmes, in favor of Π

There is no reason to doubt that these prints in their ensemble and in all their details, in their design and particular combinations of figures, lines, and colors, are the original work of the plaintiff's designer.

A picture is nonetheless a picture, and nonetheless a subject of copyright, that it is used for an advertisement.

judgment of the Circuit Court of Appeals is reversed, cause remanded to

Circuit Court with directions to set aside the verdict and grant a new trial

we see no reason for taking "connected with the fine arts" as qualifying anything except the word "works"

these chromolithographs are "pictorial illustrations" and the antithesis to

"illustrations or works connected with the fine arts" is not works of little merit or of humble degree, it is "prints or labels designed to be used for any other articles of manufacture"

it would be a dangerous undertaking for persons trained only in the law to constitute themselves final judges of the worth of pictorial illustrations

Harlan (and McKenna), dissenting

if a picture has no other use than that of a mere advertisement, and no value aside from this function, it would not be promotive of useful arts

if a mere label simply designating or describing an article to which it is attached, and which has no value separated from the article, does not come within the constitutional clause upon the subject of copyright, it

14

must follow that a pictorial illustration designed and useful only as an advertisement, and having no intrinsic value other than its function as an advertisement, must be equally without meaning

promoting the progress and science and useful arts does not embrace the mere advertisement of a circus

Class Notes is an advertisement in the scope of copyrightable subject matters? o answer (according to Holmes' majority) is yes

court is not going to judge whether something is an useful art o not going into value judgment o work is no less connected to the fine arts just because it is designed to attract customers or to promote the sale of a product

a picture is a picture, regardless of how it is use o so Holmes cautions that judges should not evaluate the merit of

General Limitations on Copyright an expressive work

Harlan's dissent o a mere advertisement is not covered by the Copyright Clause of the Constitution

that clause was meant to promote the advancement of science and useful arts

a commercial work, a mere advertisement, does not do that, and does not deserve protection o this smacks of elitism (he knows what fine art is)

I.

Idea/Expression Dichotomy a.

ideas are not copyrightable i.

inhibit discourse and discussion, the person who has the idea copyrighted is the only one who will be able to talk about it or discuss it

1.

the social cost would be enormous

2.

need to be able to have people discuss it ii.

it's hard to define what an idea is

1.

they're abstract and amorphous, hard to delineate their boundaries

2.

hard to protect, the administrative cost would be enormous

3.

but there's a problem if can't define "idea," where does "expression" begin? a.

even under current system, still have problems b.

need to figure out where the expression is, and where the distinction lies iii.

optimal choice of assets (asset configuration)

1.

in designing property systems, need to decide what underlying asset is

2.

some are more suitable for protection than others

3.

could have decided that idea is the basic unit of property, but instead took the next step – the expression

4.

don't want people to just stop at an idea, want to broaden and encourage, make people express b.

the idea/expression dichotomy expressed in Baker v. Selden i.

copyright protects the expression of an idea but not the idea itself ii.

any ideas contained in the work are released into the public domain, and the author must be content to maintain control over the form in which he first clothed his ideas iii.

there may be a possibility of protecting disclosure of the idea to others under circumstances that suggest a confidential relationship or might imply a contract

1.

this would be under state property protection, not federal copyright law iv.

***copyright law does not protect ideas, only expressions of ideas c.

there are multiple implications to Baker v. Selden i.

the most straightforward statement is that "blank account books are not the subject of copyright" the

Blank Form Doctrine

1.

most courts and the U.S. Copyright Office's regulations (37 C.F.R. § 202.1(c)) bar protection for

"blank forms . . . which are designed for recording information and do not in themselves convey information")

2.

extension of the basic principle that originality is the touchstone of copyright protection – works in which the creative spark is utterly lacking or so trivial as to be nonexistent are not protected ii.

but the Court in Baker also seems to assume that the accounting book (comprised mostly of forms) was copyrightable but the copyright was not infringed

15

1.

if the information cannot be used without "employing the methods and diagrams used to illustrate it," then those methods and diagrams are free to the public for purposes of "practical application" – but not for the purpose of publication in other works explanatory of the art

2.

1) perhaps this was a distinction between the rights protected under patent and copyright a.

patent does enable the exclusion of others from making, using, or selling a patented invention, including its underlying idea

3.

2) this has also been interpreted to mean that certain kinds of works, intended for practical application, are characterized by a high degree to integration between their ideas and the mode of expression so for these works, Baker creates exception for "takings for application or use" a.

key examples are accounting forms and computer programs

4.

3) Nimmer's treatise on copyright interprets the holding as a takings "for practical application" in situations where the use of the "art" or idea, which the copyrighted work explains, necessarily requires a copying of the work itself a.

when there is only one way to express a given idea, the plaintiff's copyright in the work as a whole does not protect the idea against use by others

5.

4) or perhaps the Court recognized intuitively that there were only so many ways to express the idea of accounting books (only so many ways to arrange the ledger), so that if an author could copyright all the possible permutations, he'd have a copyright over the idea itself d.

related cases i.

Baker v. Selden (account books)

Citation

Facts

Issue

Court's

Ruling

Class Notes

Baker v. Selden

101 U.S. 99 (1880)

plaintiff, Selden, obtained copyright for book he wrote, explaining and exhibiting a peculiar system of bookkeeping (had sample ledgers in book)

also took the copyrights of several other books, containing additions to and improvements upon said system

filed a complaint against the defendant, Baker, for an alleged infringement of these copyrights

1.

Whether the conceptual ideas contained within a bookkeeping book are protected by copyright law – whether the exclusive property in a system of bookkeeping can be claimed, under the law of copyright, by means of a book in which that system is explained.

Justice Bradley, in favor of Δ

Whilst no one has a right to print or publish his book, as a book intended to convey instruction in the art, any person may practice and use the art itself the use of the art is a totally different thing from a publication of the book explaining it.

The description in a book, though entitled to the benefit of copyright, lays no foundation for an exclusive claim to the art itself.

decree of the Circuit Court reversed and the cause remanded with instructions to dismiss complainant's bill

where the truths of a science or methods of an art are the common property of the whole world, any author has the right to express the one, or explain and use the other, in his own way

a clear distinction between the book, as such, and art which it is intended to illustrate – no one would contend that the copyright of the treatise would give exclusive right to the art or manufacture described therein o that is the province of letters patent, not of copyright

the very object of publishing a book on science or the useful arts is to communicate to the world the useful knowledge which it contains – object would be frustrated if the knowledge could not be used without incurring the guilt of piracy of the book

plaintiff's book has: o introductory essay explaining the system o appendix with a lot of blank forms

defendant did not copy the plaintiff's explanation but used similar forms

(some of the headers had been changed)

court finds no infringement

16

o cannot copyright an entire accounting system by explaining the method of bookkeeping in a book

cannot copyright an idea, you'd have a monopoly over the whole system o can copyright your explanation of it

since the defendant didn't copy the essay, there is no infringement

not every taking/borrowing will be considered a copyright infringement o true, he did use those forms o but first must decide what elements of the plaintiff's work are entitled to copyright protection and only these elements cannot be taken without permission

the rules we can get from the case o the idea/expression dichotomy: cannot copyright an idea, can only copyright your original expression of that idea (not the underlying idea) o the merger doctrine: protection will be withheld from original expression when the expression and the underlying idea merge o patentable subject matters cannot be claimed under copyright law o blank forms are not copyrightable

most straightforward and narrow holding of this case

the internal regulations of the Copyright Office exclude forms from copyright (27 C.F.R. § 202.1(c)) ii.

Eldred v. Ashcroft (note case – term extension)

1.

537 U.S. 186 (2003)

2.

recently, the Supreme Court identified this idea/expression distinction as one of the two major copyright doctrines that protect the values of the First Amendment

3.

1) the idea/expression distinction and 2) the fair use doctrine iii.

Herbert Rosenthal Jewelry Corp. v. Grossbardt (note case – bee pins)

1.

436 F.2d 315 (2d Cir. 1970), p. 124

2.

the plaintiff produces jeweled bee pins

3.

plaintiff charges defendants with infringing its copyright in a bee-shaped pin made of gold

4.

the circuit rules for the defendant, saying that the bee pins are just an idea, and the defendant only copied an idea which he was free to copy a.

there is no great difference between the products than the difference that can exist between jewel-encrusted bee pins

5.

many people view this as a merger case, too

6.

interestingly, a year earlier, brought a suit against a different defendant who created a rubber mold that could make exact replicas of the pin a.

the court in that case found infringement b.

very unsympathetic defendant i.

did not add anything original of his own ii.

perhaps fairness intuitions also play a role in these outcomes iv.

Satava v. Lowry (note case – jellyfish sculpture)

1.

323 F.3d 805 (9 th Cir. 2003)

2.

plaintiff made a jellyfish sculpture, encased in glass, and sued defendant who made similar

3.

case went the way of an idea/expression suit

4.

court found that it could not be protected under the idea/expression dichotomy a.

held plaintiff possesses "a thin copyright that protects against only virtually identical copying" b.

the expression of the defendant was not identical i.

easier to gear the court towards idea/expression when the defendant did work of his own

II.

Merger Doctrine a.

merger i.

occurs when there is only one or two ways of expressing a given idea ii.

as a result, none of the expressions are protected iii.

merger is not a technical doctrine, is a policy tool

17

1.

court is striking fine balances b.

idea/expression compared to merger

Idea Idea i.

idea/expression doctrine = many ways to express, unlimited

1.

all of the methods of expression are copyrightable

2.

this is addressing a larger issue a.

is about scope ii.

merger = the number of ways of expression of an idea are limited

1.

so nothing is protected

2.

because the number of ways of expression are so close to the idea itself, then it's better to not protect the expressions at all so that the idea can be communicated openly

3.

this is addressing a different issue than idea/expression doctrine a.

is about copyrightability iii.

practical implications between the two doctrines is huge

1.

in suit, idea/expression loss is better for the plaintiff because can still protect the expression against other people

2.

merger is an extreme result ends up opening up the entire idea and all expressions c.

related cases i.

Morrissey v. Proctor & Gamble (note case – sweepstakes language)

1.

379 F.2d 675 (1 st Cir. 1967)

2.

the plaintiff sues, alleging defendant copied its sweepstakes rules a.

the defendant had copied the rules verbatim

3.

court finds no infringement a.

finds it on grounds of merger! b.

the plaintiff's idea can be expressed in only in a limited number of ways, and therefore there should be no protection

4.

is this really merger? a.

there's no point, waste of resources to rewrite b.

the language would become more complicated and complicated, and people can't understand it c.

want to be clear and effective expression, don't want to be monopoly on the clear rules

(only a few ways to express it clearly) i.

makes it harder on the consumers ii.

CCC Information Services, Inc. v. Maclean Hunter Market Reports, Inc. (note case – Red Book)

1.

44 F.3d 61 (2d Cir. 1994)

2.

Maclean is the publisher of the Red Book, a compendium of used car prices

3.

sues CCC, after CCC took its entire price compilation and put it on a computer database a.

as defense, claiming that the compilation of prices are facts and they cannot be copyrighted, only so many ways to say it

4.

brings up similar fairness issues of INS v. AP

5.

the court held that there was a copyright infringement a.

but how did they get there? if there is any merger, it'd be here b.

not very clean decision, problematic c.

distinguished between "hard ideas" (ideas that undertake to advance the understanding of phenomena or solutions to problems, math or science) and "soft ideas" (ideas that are infused with the author's taste or opinion) i.

used car prices fall into the second category

1.

more art than science d.

for soft ideas, the court was willing to suspend the merger theory e.

bolsters argument by referring to incentive theory i.

would completely undercut incentive to find used car prices f.

also points to notions of fairness g.

bent the law a little, and reached the result it wanted to

6.

this case is the mirror image of Morrissey

III.

Government Works - § 105

18

a.

the 1976 Act unambiguously provides in § 105 that copyright protection "under this title is not available for any work of the United States Government" i.

§ 101 defines the "work of the United States Government" as "work prepared by an officer or employee of the United States Government as a part of that person's official duties" ii.

note this is the federal government b.

requirements i.

1) prepared by an officer or an employee of the U.S. government (use the agency test from labor law) ii.

2) as a part of that person's official duties c.

exceptions i.

§ 105 does not bar copyright protection for works created for the government by independent contractors (Schnapper v. Foley) ii.

does not extend to works created by employees of the U.S. Postal Service iii.

15 U.S.C. § 290(e) specifically provides that the Secretary of Commerce may secure copyright on behalf of the United States in "standard reference data" compiled and evaluated by the National Institute of

Technology and Standards in different areas of science and engineering

1.

to promote the dissemination of this data by facilitating its licensing to private publishers iv.

the National Technology Transfer and Advancement Act of 1995 (15 U.S.C. § 3710) was intended to assure that private industry "partners" of federal scientific agencies could enjoy title to patents in inventions arising out of Cooperative Research and Development Agreements (CRADAs), and that federal government employees could receive royalties from their inventions under the same circumstances v.

by its own terms, it only applies to the federal government, so no restrictions are placed on state and government ownership by this § itself

1.

provisions of state law may dictate public availability, too d.

statutes and ordinances = the law i.

these types of government works are part of the public domain and cannot be subject to copyright ownership by any government

1.

copyright is an exclusion doctrine, and we want no one excluded, want everyone to have access to the laws ii.

citizens must have free access to the laws governing them

1.

all matters being produced by the government are important to institution of democracy

2.

government is not a private actor, is an entity belonging to the people

3.

people elect officials and vote perhaps the public is the ultimate authors iii.

a grey area is when the statute or ordinance is drafted by a private party e.

state laws i.

a longstanding judicial tradition precludes copyright protection in state laws, regulations, and court decisions ii.

by virtue of judicial tradition, we have unimpeded access to laws and court decisions viewed as inherently public, and not entitled to copyright protection f.

foreign documents i.

the reach of § 105 was not intended to affect the U.S. copyright status of foreign government documents ii.

works by most other countries' governments are copyrighted at home, and can be protected in the

United States as well g.

collaborations i.

the normal rule is that works of U.S. government are not protected under copyright ii.

but when a private individual or company collaborates with the government, is a case of joint authorship does it change the underlying policy?

1.

patents a.

the National Technology Transfer and Advancement Act (NTTAA) i.

assures that private industry partners can secure patent protection

2.

copyrights a.

not as clear, so similar act that takes care of the copyright question b.

contractual provisions become very important i.

the way that the ownership of copyright is taken care of in the contract can affect how the court will analyze the situation after the fact c.

although there isn't a clear answer, the contract agreement affects the willingness of the court to recognize copyright protection h.

commissioned works i.

becoming a very widespread phenomenon

19

ii.

the government relies more and more on private companies as far as production of standards is concerned

1.

standards = building codes, product safety codes, accounting principles, etc.

2.

government is outsourcing the drafting a.

then enacts those standards written iii.

becomes a part of the law, but was written by a non-governmental entity

1.

also not freely available i.

related cases i.

Wheaton v. Peters (note case – federal statutes)

1.

33 U.S. (8 Pet.) 591 (1834)

2.

federal statutes, regulations, and judicial opinions are not subject to government copyright ownership ii.

Matthew Bender & Co. v. West Publishing Co. (note case - headnotes)

1.

158 F.3d 674 (2d. Cir. 1998)

2.

"value-added" materials, such as summaries and headnotes, are subject to private copyright protection iii.

Schnapper v. Foley (note case – independent contractors for govt)

1.

667 F.2d 102 (D.C. Cir. 1981)

2.

§ 105 does not bar copyright protection for works created for the government by independent contractors

3.

case was about a television documentary produced by public broadcasting entities iv.

Veeck v. Southern Building Code Congress International (privately drafted codes)

Citation

Facts

Issue

History and

Precedent

Court's

Ruling

Veeck v. Southern Building Code Congress Int'l, Inc.

293 F.3d 791 (5 th Cir. 2002)

plaintiff Veeck owns and runs a non-commercial website that provides information about northern Texas

he was not able to easily locate the 1994 edition of the Standard Building Code written by the defendant, SBCCI, so he eventually bought the model codes directly from SBCCI for $72

even though the software came with a licensing agreement, he cut and pasted the text onto his website – he did not identify them as written by SBCCI, but correctly identified them as the building codes of Anna and Savoy, Texas

1.

Whether a privately-written code, later adopted into state law, is subject to copyright enforcement.

Wheaton v. Peters o "no reporter has or can have any copyright in the written opinions delivered by this Court" o "the law" in the form of judicial opinions may not be copyrighted

Banks v. Manchester, 128 U.S. 244 (1888) o denied a copyright to a court reporter in his printing of the opinions of the Ohio Supreme court o whatever work judges perform in their official capacity cannot be regarded as authorship under the copyright law o the whole work done by the judges constitutes the "authentic exposition and interpretation of the law, which, binding every citizen, is free for publication to all, whether it is a declaration of unwritten law, or an interpretation of a constitution or statute"

Building Officials and the Code Adm. V. Code Technology, Inc., 628 F.2d 730

(1 st Cir. 1980) o the metaphorical concept of citizen authorship of the law, together with the important and practical policy that citizens must have free access to the laws which govern them

Judge Jones, in favor of Π

SBCCI is creating copyrightable works of authorship when they write and public model building codes when those codes are enacted into law, however, they become to that extent "the law" and may be reproduced or distributed as the law of those jurisdictions.

as the organizational author of original works, SBCCI indisputable holds a

20

Concurrence or Dissent

Class Notes copyright in its model building codes

we read Banks, Wheaton, and related cases consistently to enunciate the principal that "the law," whether it has its source in judicial opinions or statutes, ordinances or regulations, is not subject to federal copyright law o codes are "facts" under copyright law – the unique, unalterable, expression of the "idea" that constitutes local law

as governing law, pursuant to Banks, the building codes of Texas cannot be copyrighted o is not about author's incentives (utilitarian) or adequacy of access (due process) arguments o Banks declares at the outset of its discussion that copyright law in the

United States is purely a matter of statutory construction

the lawmakers represent the public will and the public are final "authors" of the law – even when a government body decides to enact proposed models of building codes, it does so based on legislative considerations

disagree that the question of public access can be limited to the minimum availability that SBCCI would permit

Judge Higgenbotham, dissenting

would affirm the judgment of the district court

it is undisputed that Veeck copied the copyrighted product of SBCCI

that parts of the copyrighted material contain the same expressions as the codes of two Texas cities is no defense unless the cities' use somehow invalidates SBCCI's copyright

a complex code, even a simple one, can be expressed in a variety of ways

not yet willing to embrace that invalidity of copyright is the inevitable consequence of code adoption

rather, conclude that Veeck violated the explicit terms of the license he agreed to when he copied model codes for the internet and decide no more

Judge Weiner, dissenting

in holding Veeck under the discrete facts of this case, the majority had to (and did) adopt a per se rule that a single municipality's enactment of a copyrighted model code into law by reference strips the work of all copyright protection,

ispo facto

believe that for this court to be the first appellate court to go that far is imprudent

as Veeck cannot legitimately find a safe haven in any of his affirmative defenses, the district court's order should have been affirmed

Veeck, who ran a non-commercial website, purchased a copy of the building codes directly from SBCCI o had no choice, had to purchase to get access

trial and Fifth Circuit panel ruled in favor of SBCCI, and Fifth Circuit rehearing en banc o found no liability, ruled for Veeck on two separate grounds

1) the law is not protected under copyright

the law, whether articulated in judicial opinions or in legislative acts or ordinances, is in the public domain and thus not amenable to copyright protection the building codes of the two towns are no exception to the general rule

in a democratic system, the people are the authors of the law and should therefore have free access to it

once something is made into law, cannot claim copyright in the expression

2) the merger doctrine

even if the code comes under the copyright law, copyright protection should be withheld in this case on grounds of merger

there is only one precise way to express what the law

21

is

once the work is enacted into law, once it gains status v.

P of the law, it becomes the law (merger occurs) o protection can no longer be claimed r a

dissenting opinions c o dis-incentivizing these companies from helping the government to draft these standards and regulations (which the government is i t increasingly relying on private actors to do) c o believe the majority opinion is overbroad and overreaching o must afford protection to such codes and other standards that were e produced by private companies

M g m

is copyright really needed? o ex ante contracting – can decide how much effort to put into production of standards because already getting paid for it o even if there is no free market on the good…

.

t this is a form of soft lobbying – they get input in their own regulations

there are other complimentary services you can sell

I n

explanations of the code, headnotes, etc. o the standards are common f they aren't identical, but they're probably not too different o

. Corp. v. Amer. Med. Ass'n (AMA) (note case – medical procedure coding system)

1.

121 F.3d 516 (9 th Cir. 1997)

2.

the Circuit affirmed a ruling that the AMA did not lose its copyright in medical procedure coding system when the system became required by government regulations

3.

why? their reasoning: a.

regulatory agencies could terminate agreements or adopt regulations requiring private standards-setting companies to increase access or facilitate access b.

courts could enlarge the defense claims (fair use and due process) c.

legislatures can adopt compulsory licensing agreements to enable greater access

4.

all these mechanisms seem costly to implement a.

depend on push/pull of politics b.

litigation especially is costly (not easy to prove fair use) i.

people would probably end up paying, in practice, because cheaper than court c.

would not implement any of these mechanisms, would just pay for the copy

Subject Matter – Works of Authorship

I.

Works of authorship, generally a.

the product of the mind that is protected by copyright is not the medium of expression, but rather the intangible expression itself, apart from the material object i.

making a distinction between the copyright of the work of authorship (the song) and the material object in which the work is fixed (the record) b.

§ 102(a) of the 1976 Act originally listed 7 categories of works of authorship i.

added an 8 th category (architectural works) in 1990 ii.

categories are narrower (many works fit that within the description of the category are denied protection by virtue of other statutory provisions) and broader (works addressed in other §§ of the Act like compilations and derivative works are merely examples of the categories) iii.

the list is not closed – "illustrative and not limitative"

1.

flexible to adopt the law to new technologies and media

2.

Congress took pains to ensure that qualifying works would be protected regardless of their mod of fixation, whether or not the means were known or developed when the Act passed

3.