Crotty & O'Donoghue on studying religious world views

advertisement

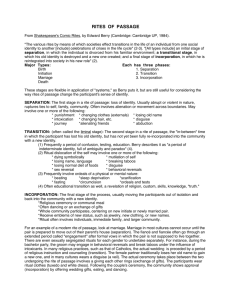

Crotty, R., & O’Donoghue, M.* A strategy for teaching about the religious worlds of today Education 51 (2) 2003 19-23 Crotty, R. & O’Donoghue, M. (2003). A strategy for teaching about the religious worlds of today. Journal of Religious Education 51 (2) 2003 19-23. A strategy for teaching about the religious worlds of today Some time ago, the five original authors (Marie Crotty, Norman Habel, Basil Moore, and the two authors of this article) of the secondary text book Finding a Way. The Religious Worlds of Today, consisting of a Student Book (1989) and a separate Teachers Book (1989), were asked by HarperCollins to prepare a second edition (to appear 2003). Prior to the writing of the first edition, the five of us had already become adept at working together. We had taken on joint research that entailed us meeting for weekends in adjoining units in a South Australian resort. We appreciated each other's talents and we readily undertook the commission. The first edition had been the result of face to face planning meetings at which we each presented drafts of disparate sections for consideration and critique. The five of us represented a variety of expertise in the history of religions, sociology of religion, religious literature, curriculum studies, feminist studies, studies in racism. Slowly the text book took shape. The end result of the joint exercise was that it became difficult to differentiate between the individual contributions. Eventually we matched a curricular approach to the study of religions with a textbook that would provide the basis for such a curriculum. Besides writing the Teachers Book to accompany the Student Book we also presented a joint paper at an Australian Association for the Study of Religions Conference in 1990 in order to explain to religious educators how we thought the textbook should be used. Further, each of us has been asked over the years to speak to the textbook and to explain how it should work and we have run workshops to do just that. In retrospect, how successful was the project? Probably not a resounding success. The Student Book has sold well (as is witnessed by the number of printings and now the request for a second edition), but our suspicion has been all along that only certain selected sections have been used by teachers and that the explanation of the curricular approach in the Teachers Book has not been taken as seriously as we would have hoped. For the second edition the five of us (admittedly now showing the unmistakable signs of ageing) met again, first over working lunches and then electronically (largely unavailable for the first edition). We saw the need to make some corrections to the Student Book, to include material on the religious traditions in Australia, to bring some of the data up to date, to make projects more topical to the problems of the third millennium and to include reference to some important electronic sources. However, unanimously we considered that the original thrust of the Student Book and the methodological approach described in the Teachers Book were still relevant. The book was written on the premise that Australia is a multicultural country and that this trend would only continue to be more prominent. Few would contest that. Multiculturalism inevitably brings in its train religious pluralism, in the broad sense of a number of religious traditions existing in the same society. But we had sounded a warning: In schools where there is a great deal of religion in the curriculum, there is often little multiculturalism. In schools where there is a great deal of multiculturalism, there is often little religion. (Teachers Book, p. 2) Our survey showed that religious education was prominent in schools with religious foundations but overwhelmingly these religious education programs dealt exclusively with the tradition in which the school was embedded. Many public schools took multiculturalism seriously, as also did Catholic schools, since there is no community group in Australia that is more representative of multiculturalism than the Catholic Church. However, these multicultural programs, by and large, focussed on almost every facet of culture other than religion. There has been nothing in more recent Australian history to dissuade us from continuing in the direction that we had originally taken - towards a Journal of Religious Education 51 (2) 2003 19 confrontation with religious pluralism. In an article published in this journal in 2001 it was concluded: Given this brief overview of the situation in contemporary Australian society and informed by approaches to developing a tolerant and open multicultural society through education and interaction, it is apparent that religious education needs to be designed specifically to encourage and facilitate religious pluralism within a multifaith and multicultural Australia. (Wurst & Crotty, 2001. p. 30) Our fundamental apologia for constructing a textbook on the ‘religious worlds of today’ was simply that ‘we do not believe there is any great virtue in being illiterate’. That remains our position. While illiteracy as such is decried in our society, yet it remains a fact that most Australians are socially illiterate when it comes to religion. We stated rather bluntly in 1989: ... both denominational and state schools have contributed to this religious illiteracy and continue to do so. How many students leaving any school would be able to say three intelligent things about Sikhism? Or tell the difference between the Buddha and an ayotallah? (Teachers Book, p. 2) By the end of this article, we hope that what we meant by ‘religious literacy’ will be more evident. We then went on to make a statement that has been only too cruelly reinforced in the intervening period culminating in September 11, 2001 and October 12, 2002: And in the modern world, basic religious literacy is not irrelevant. There have been major international and national crises and conflicts in which religion has been a key issue. It is impossible to understand let alone respond intelligently to such events without having some understanding of their religious aspect. (Teachers Book, p. 2) Our hope was to bring about an awareness of religious pluralism, understood not simply as the fact that many religions co-habit Australia, but understood as a program whereby people respect and understand other religious traditions, recognising that religions are ‘true’ for the people who follow them, bringing ultimate meaning and purpose into their lives. We made the following statement: 20 Journal of Religious Education 51 (2) 2003 We hope that religious pluralism will become a much more significant feature of the Religious Education programme in denominational schools. We hope also that religious pluralism will be treated in greater depth in the multicultural programmes in all schools. (Teachers Book, pp. 3-4) With these purposes in mind we established our teaching methodology. The Student Book is arranged so that it can be read in two directions: reading the text horizontally (to identify and compare particular characteristics common to some or all religions) and reading the text vertically (to see the inner logic that presents a coherent system of belief and practice with its own integrity and its distinctive influence on the faith and life of its adherents). In order to facilitate these two ways of studying religion we then chose two ‘process’ approaches to teaching, best suited in our opinion to the two ways of studying religion - the Concept Attainment Model and the System Construction Model. These are not the only approaches to teaching religion, but we decided to concentrate on them. As the name suggests the Concept Attainment Model helps the student understand and clarify concepts, the fundamental building blocks in human communication. In the case of religious concepts, the Concept Attainment Model uses the horizontal reading method to help students draw out and identify the similarities and differences in the many aspects of the different religions (such as beliefs, sacred stories, religious experience, religious ritual, social structures, sacred texts, religious ethics, sacred symbols). The System Construction Model helps the student to link together or synthesise what appear to be very different concepts. Human systems can be very complex and the connections that make them up are not immediately obvious. This is especially true of religions. A central and recurring theme, idea or value helps to link the various major concepts within a particular religion and the student should understand how all of these form a unified whole. Applied to the study of religion, the Concept Attainment Model can be broken down into a series of phases. While the phases may seem rather artificial at first sight, the experienced teacher can eventually move from one to another in a relaxed and natural fashion. Teacher preparation Selection of a religious concept that we can identify as ‘x’ (not a religious theory or a religious fact), clarification of its basic and distinguishing features and identification of appropriate examples. Phase 1. What do we think that x means? (Presentation of the concept) Phase 2. What do others mean by x? (Presentation of instances from linguistic culture) Phase 3. This is an x (but this is not) (Presentation of ‘labelled’ phenomenal exemplars) Phase 4. Is this really an x? (Initial testing of concept attainment) Phase 5. This is what x means. (Formulation of a set of distinguishing characteristics of the concept) Phase 6. Here's another x (Test attainment of the concept) Phase 7. How did we come to know x? (Analysis of thinking strategies used) The System Construction Model can be likewise broken down into a series of phases. Teacher preparation A sound knowledge of all the major aspects of the religion under investigation - its core beliefs, values and practices. Phase 1. What do we think are the main points. (Initial description of core features) Phase 2. What's in it. (Analysis of major components) Phase 3. What are the main points (Review of core features) Phase 4. Does it hang together? (Synthesis of major components) Phase 5. Hey Presto! A (Presentation of the system) living religion. An example of the horizontal study of religion using the Concept Attainment Model might be a series of classes on the concept of ‘rites of passage’. Teacher preparation The teacher would need to do some background reading on the topic, taken from Anthropology or Religion Studies. Rites of passage include rituals for birth, puberty, initiation, marriage and death as well as the rituals that accompany induction into special offices, such as the priesthood, monastic state or shamanism. There are characteristics of rites of passage that textbooks on anthropology and religion will readily tabulate. Phase 1. What do we think ‘rites of passage’ means? The students are encouraged to discuss what they think the concept of ‘rites of passage’ entails from ideas of ritual that have accompanied important life-transitions in their own experience such as the birth of a child, marriage, death or perhaps a priestly ordination. They are asked to list the more important characteristics of these special rituals. They would probably pick up such characteristics as the inclusion of the person in a new status, the person’s separation from a previous world, some ritualistic marking of the candidate, the presence of sponsors. Phase 2. What do others mean by ‘rites of passage’? By offering the students some resources (Finding a Way has some ready-made Resource Sheets, but there are other possibilities), they can extend their enumeration of the characteristics of rites of passage. Phase 3. This is a ‘rite of passage’ (but this is not) From a Resource Sheet, video, field trip, library search and so forth the students can study an actual rite of passage (for example, the Sacred Thread ceremony for Hindu boys). They know from the outset that it is a rite of passage. They can be asked to identify the major characteristics that appear from the presentation and then fill out a Worksheet (also supplied) using them. They are moving towards comprehending a pattern of rites of passage. Phase 4. Is this really a ‘rite of passage’. In this phase the students are presented with the description of a ritual (either orally, by medium of video or by attendance) but they are not given any assurance that it is a rite of passage. Using their list of characteristics they should be able to conclude whether or not it is, in fact, a rite of passage. Phase 5. This is what ‘rite of passage’ means. The students by this stage have in their possession a list of characteristics and they would have considered a number of examples of rites of passage. The aim is now to assist them to select those characteristics that are essential to the concept and that help them distinguish it from other similar concepts. A class could be divided into groups and each group entrusted with a distinguishing characteristic. They could give examples of that characteristic from the rituals that they have encountered. Journal of Religious Education 51 (2) 2003 21 Phase 6. Here’s another ‘rite of passage’ By this point the students should be given the opportunity to demonstrate how they understand ‘rite of passage’ by constructing their own exemplar that can take the form of a fictitious story or presentation. In story or report form they can describe some dramatic turning-point in a person’s life and report on their own construction of a rite of passage that could accompany it. Phase 7. How did we come to know the ‘rite of passage’? By group or class discussion, the students identify the development of their own understanding of a rite of passage. At the conclusion of this set of study sessions, the students should be able to identify the major features of a rite of passage, be able to discuss the significance of rites of passage for the individual and society and name some rites of passage in different religious traditions. An example of a vertical study of religion using the System Construction Model would be a series of lessons devoted to Islam. Teacher preparation The teacher would need to ensure that his/her understanding of Islam was without bias (for example, Islam does not equal terrorism). A short list of essentials would be: Beliefs: the oneness of Allah; the prophetic role of Muhammad; Djinn; angels and Satan; Day of Judgement; eternity of the Qur'an. Values: islam (submission); jihad (striving) Structures: lay-out of the mosque; role of imam; festivals (especially Id-ul-Fitr and Id-ul-Adha) Practices: the five Pillars (confession of faith in Allah, prayer on five occasions during the day, almsgiving, the fast during the sacred month of Ramadan, a pilgrimage to Mecca at least once in a lifetime); recitation of the Qur'an; Sufi practices. Phase 1. What do we think are the main points? Using a variety of resources, texts and video for example, the students can be asked to identify what they see as the core features of Islam that distinguish it from other religions. They may highlight the role of the prophet Muhammad, the central authority of the Qur’an, the human attitude of submission to Allah. Phase 2. What's in it? 22 Journal of Religious Education 51 (2) 2003 Finding a Way outlines the eight major components of a religion (see also Crotty, 1995). The students are encouraged to develop empathetic descriptions of each of these eight components in Islam. These are described at length in Finding a Way. Phase 3. What are the main points? By class discussion on the work done in Phase 2 and further examples from other resources the students are helped to revise and extend the list of core and distinguishing features of the religion. Phase 4. Does it hang together? The aim here is to see how the core features identified in Phase 3 are present in the major components identified in Phase 2 and that the core features give a distinctive quality to each of the components. On a chart connecting links between components and core features can be drawn. The Teachers Book gives a example of such a chart. Phase 5. Hey Presto! A living religion. In this final phase the students are given the opportunity to communicate the sense of Islam as an integrated system. This can be done by different media. For example, a student or a group could make a class presentation on a recent pilgrimage to Mecca; on being present at a mosque at the Friday service; on the daily duties of the Muslim; on the reading of the Qur'an; on why ‘I am a Sunni Muslim (or a Shi'ite Muslim)’. The presentation could include oral description, play acting, collages or posters. At the end of this exercise, these students should be able to present competently the main beliefs and practices of Islam. They should be able to distinguish the Islamic religion from the violent excesses of fanatics who seek to legitimate their actions by appeals to their religion. They should be able to appreciate the beauty and depth of the Qur'an. This broad study of religion, with its horizontal and vertical aspects, is the basis for what we have termed religious literacy. This has been described as follows: The developing youth would need to know the structure of religion, the interrelationship of its parts and need to appreciate the direction and purpose that religion could give. Certainly there would also need to be an introduction to a variety of religious traditions in order to make the theory concrete and understandable. The educational outcome should be a fluency in dealing with religious terminology such as ‘myth’, ‘ritual’, ‘religious experience’, ‘religious ethic’, together with the ability to give concrete examples. This form of religious education should be provided by all educational institutions within Australian society, state or private. It should be regarded as essential as literacy or numeracy, and indeed it could be compared analogously to the teaching of English as one of the overarching values that holds secular society together. (Crotty, 1996, p. 192) This is not to deny that at the same time the youth may receive instruction in one or other religious tradition, although this is not the primary concern of the state system. The analogue here would be the teaching of a family language and its attendant culture. Just as a child of Greek parents should learn to communicate in English, to be literate, but also receive instruction in Greek communication (perhaps in a Greek Saturday school), so the same child could be schooled in religious literacy and be inducted into the study of Greek Orthodox religion. Mutatis mutandis, the same principle holds for the Roman Catholic child or any other. Primarily, this particular religious instruction pertains to the family and to religious institutions, educational and other. This form of religious instruction does not form part of Finding a Way, but we would maintain that what we have done in the book should be articulated with a variety of religious instruction courses. In whatever case, the very best pedagogy and the best curriculum should be utilised. Our final word to the students in Finding a Way still stands in the second edition. We will let the religions speak for themselves and each describe its ‘world’, but we will also give you the opportunity to be critical and to express your own views on the religions. (Student Book, p. 3) We sincerely hope the orientation towards religious pluralism, which we regard so seriously, is taken into account in any attempts to rethink religious education in Australia. References Crotty, R. (1996). Religious education in a pluralist society. In G. Potter (Ed.), Heritage of faith: Essays in honour of Arnold D. Hunt. Flinders Press: Adelaide Crotty, M. et al. (1989). Finding a way. The religious worlds of today, Teachers Book. Collins-Dove: Melbourne. Crotty, M. et al. (1989). Finding a way. The religious worlds of today, Teachers Book. Collins-Dove: Melbourne. Crotty, M. et al. (1989). Finding a way. The religious worlds of today, Student Book. Collins-Dove: Melbourne. Crotty, R. (1998), Studies in religion in a pluralist society. Intersections 4 (1), 21-34. Crotty, R. (1995). Towards classifying religious phenomena. Australian Religion Studies Review 8, 34-41. Wurst, S. & Crotty, R. (2001). Establishing the foundations of RE in contemporary Australian society. Journal of Religious Education 49(2), 26-30. *Robert Crotty is Adjunct Professor of Religion Education at the University of South Australia. Having completed theological and biblical studies in Rome and Jerusalem, he later did a research degree in ancient history at Melbourne University and a doctorate in education at Adelaide University. His present research interests are the history of early Christianity and pluralist religious education. *Michael O'Donoghue is Senior Lecturer in the School of Education at the University of South Australia. He is Program Director of the Bachelor of Education (Graduate Entry) and coordinator of the Religion Studies subject area. These reflect his twin interests in Education and Religion Studies. In the former his interest is in teacher education and the social context of education. In the latter his interests are in Ancient Egyptian Religion and religious phenomena. FINDING A WAY: The Religious Worlds of Today (2nd ed.). HarperCollins Religious, 2003 ISBN 1 74050 004 0 Marie Crotty, Robert Crotty, Norman Habel, Basil Moore and Michael O'Donoghue. Journal of Religious Education 51 (2) 2003 23 This updated edition is intended to help students get behind the headlines by exploring the fascinating worlds of religion openly and honestly. It invites them to walk in the shoes of religious believers and see their worlds through their eyes. It also encourages them to ask