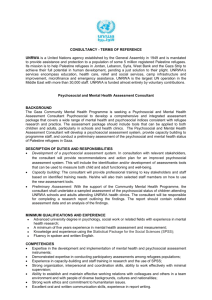

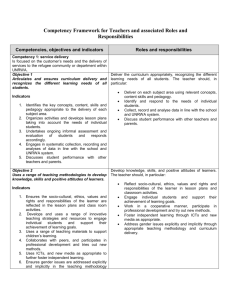

Etpu - UNRWA

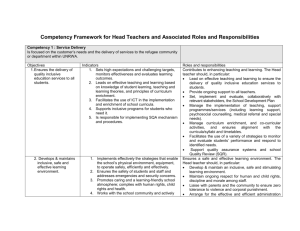

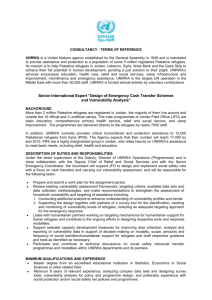

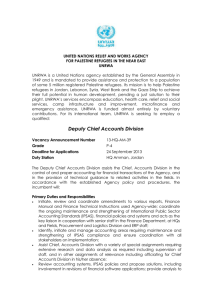

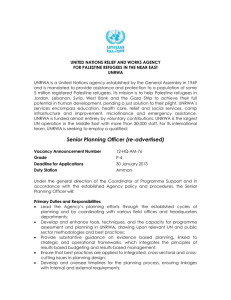

advertisement