A Note on the Scansion of Keats's

advertisement

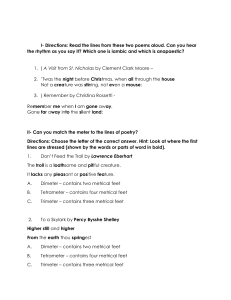

A Note on the Scansion of Keats’s “La Bella Dame Sans Merci” Alexander Tung Reprinted from Journal of Arts and History Volume IX Published by The College of Liberal Arts, National Chung Hsing University Taichung, Taiwan, Republic of China June, 1979 A Note on the Scansion of Keats’s “La Bella Dame Sans Merci” O what can ail thee, knight-at-arms! Alone and palely loitering! The sedge has withered from the lake, And no birds sing. O what can ail thee, knight-at-arms! So haggard and so woe-begone? The squirrel’s granary is full, And the harvest’s done. I see a lily on thy brow With anguish moist and fever dew, And on thy cheeks a fading rose, Fast withereth too. “I met a lady in the meads, Full beautiful—a faery’s child, Her hair was long, her foot was light, And her eyes were wild. “I made a garland for her head, And bracelets too, and fragrant zone, She looked at me as she did love, And made sweet moan. “I set her on my pacing steed, And nothing else saw all day long. For sidelong would she bend, and sing A faery’s song. “She found me roots of relish sweet, And honey wild and manna-dew; And sure in language strange she said, ‘I love thee true.’ “She took me to her elfin grot, And there she wept and sighed full sore; And there I shut her wild, wild eyes With kisses four. “And there she lulled me asleep, And there I dreamed—ah! woe betide!— The latest dream I ever dreamed On the cold hillside. “I saw pale kings, and princess too, Pale warriors, death-pale were they all: They cried—‘La belle dame sans merci Hath thee in thrall!’ “I saw their starved lips in the gloam With horrid warning gaped wide, And I woke, and found me here On the cold hillside. “And this is why I sojourn here Alone and palely loitering, Though the sedge is withered from the lake, And no birds sing.”1 Four-line stanza rhyming abcb, dialogue form, stock-descriptive phrase, refrain, the theme of love- - yes, the above poem is a ballad. But does it have the common metrical pattern of a ballad? Scanners of this poem seem to differ even on this apparently simple question. There are people, for instance, who insist on scanning the last line of each stanza as a trimeter line, seeing that it is often the case with most other ballads. Accordingly, the line “And no birds sing” is said to have two instances of “metrical silence” distributed before the words birds and sing, the meter being iambic: And no ( ) birds ( ) sing. 2 In the meantime, however, there are also people who maintain that the line should be scanned as a dimeter line with only one instance of metrical silence before the word sing while the word no is unstressed: And no birds ( ) sing. Now, which version of scanning the line is more justifiable? And my reasons are: I think the latter is. First, not all the final lines of all the stanzas can be scanned as trimeter lines while they can all be conveniently scanned as dimeter ones. For instance, it would be very awkward, if not absolutely impossible, to read the line “A faery’s song” or “With kisses four” with three heavy stresses whereas it obviously contains two iambs. We admit that many of the lines have rendered our analysis difficult because some words can receive either more or less stress, depending on our way of scansion. Nevertheless, I believe the metrical complexity of all the final lines does not make it impossible for us to analyze them as dimeter lines. In fact, if we accept the ideas of “metrical silence” and “metrical substitution,” then the analysis will be far from awkward. For example, some lines can be said to contain an anapest plus an iamb: “And the harvest’s done,” “And her eyes were wild,” “On the cold hillside.” All the others can be said to contain two iambs except the line “And no birds sing,” which, as already said, contains an anapest (“And no birds”) plus a metrical silence which, together with the following stressed word sing, constitutes an iamb. Second, it seems that Keats has no intention whatever to keep the standard metrical pattern of a ballad stanza in writing this poem. As we know, a ballad stanza usually has four lines, the first and the third of which are tetrameter lines while the second and the fourth of which are trimeter ones. Now, as we examine the poem, we find at once that the second lines of all the stanzas are all tetrameter lines instead of trimeter ones. That is, they have each of them one extra foot added to the normally trimeter lines. As a result, the first three lines of each stanza are metrically of the same length. This variation can help us to conclude that Keats may also have intended to break away from the norm of a ballad stanza by changing the number of metrical feet in the final line of each stanza. In effect, it seems that for each stanza Keats has removed a foot from the fourth line and grafted it onto the second. Third, I believe Keats has purposely made use of the metrical variation to suggest something although this “something” is open to various conjectures. Indeed, much effect is added to the ballad through “the poignant and richly suggestive suspension achieved by shortening to two stresses the final line of each stanza.”3 But doesn’t the lengthening of the second line to four stresses also give contribution to poem’s effect? I think both instances of metrical variation work together to give the reader a shock or at least a feeling of puzzlement, just as the first speaker in the poem is shocked or puzzled to find the knight-at-arms “alone and palely loitering on the cold hillside.” But why? How come the reader will feel shocked or puzzled through the metrical variation? Because, you know, after reading three tetrameter lines, one may expect the next line to be a tetrameter line, too. But since that is not the case, one cannot but be shocked or puzzled to find that the next line is only a dimeter one. Somehow, he feels it is too short; he feels it ends all too abruptly. “Yes, it is too short. It ends all too abruptly.” Not only will the reader say so, but also the knight-at-arms though he refers to his love affair with the “faery’s child” instead of to the poetic line that ends each stanza. Thus, we see the metrical variation also serves to reflect the knight’s state of mind. The three tetrameter lines build up our expectation for as long a line next, just as the knight’s stay with the elf builds up his longing for more happy days. But our expectation fails just as the knight’s hope perishes abruptly. Yet, does the metrical variation only suggest that? No. Another plausible consideration is: Since a dimeter line is literally half the length of a tetrameter line, might it not be used to suggest the now single state of the knight or the imperfection of the knight’s elfin lover? In each stanza of the poem, the last line is a dimeter one, that is, half the length of its foregoing line. Does this not suggest that at last only half (that is, one) of the two lovers is left? Meanwhile, does it not suggest that at last the lady proves only half perfect for being without pity although she is beautiful (just as the literal translation of the poem’s title means)? If we want to push the matter to an extreme, we can even use the analyzed metrical variation to account for the much-discussed question of why Keats at first writes “With kisses four” for the thirty-second line. In a letter Keats himself told his brother that he wrote the number four because he “was obliged to choose an even number that both eyes might have fair play.”4 This explanation is not satisfactory. For we may ask, “Why, then, not two or six?” Is the number four really, as he also said, a “sufficient” number to show the knight’s love on one hand and to “restrain the headlong impetuosity of [his] Muse”5 on the other? As a matter of fact, the direct and plain reason is: the word four rhymes naturally with the word sore in the thirtieth line.6 If we can give a far-fetched explanation as Keats seems to have done, I might say: “The number four is well-chosen here because four is the ‘normal’ number for the poem. It is composed of four-line stanzas. In each stanza all the lines except the last one have four feet each. As the knight finds nothing abnormal in the elfin lady at first, it is normal for him to give her four kisses.” Surely I myself may have gone too far now. But it remains that for a better effect the scansion of “La Belle Dame Sans Merci” demands our special attention to the unusual numbers of metrical feet which occur in the second and the final lines of each stanza. If we scan the final line of each stanza as a dimeter one and consider it in connection with its three foregoing tetrameter lines, then we will be in a better position to make the sound echo the sense, as the above discussion shows. And, perhaps, we can then fully see the artistic achievement in the art ballad. Notes 1. From George B. Woods, et al., The Literature of England (N. P.: Scott, Foresman 2. 3. 4. 5. & Co., 1985), II, 282. This is precisely what is suggested in Marlies K. Danziger & W. Stacy Johnson, An Introduction to Literary Criticism ( New York.: D. C. Heath and Co., 1961), p.52 See Note 1 in M. H. Abrams, et al., ed. The Norton Anthology of English Literature revised, (New York: Norton, 1968), II, 526. Quoted in Cleanth Brooks & Robert Penn Warren, Understanding Poetry, 3rd ed. (New York.: Holt, Rinehart & Winston Inc., 1960, p. 69. Ibid. 6. But Keats himself does not grant that this is the reason.