things getting better

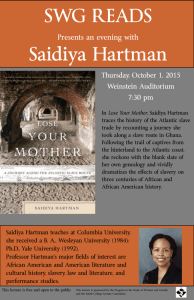

advertisement