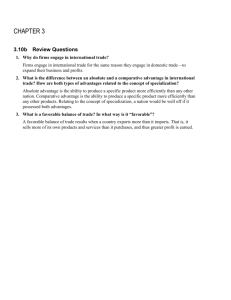

Arguments for and against trade restrictions

advertisement

Arguments for and against trade restrictions The need of protection of domestic labour markets against cheap foreign labour. Imports sometimes are believed to sweep out domestic business from the market destroying national production in the industry and contributing to the increase in the rate of unemployment. This argument may be criticised by an assessment of factors determining national competitive advantages and economic growth. Cheap labour tends to be unskilled and proves to be a factor with little importance in international competitiveness of national economies and firms. Moreover, labour is cheap mainly in traditional industries with unsophisticated home and foreign demand that do not contribute significantly to economic growth and technological development. Structural and technological changes today are shifting away industries using cheap labour and motivate workers to acquire higher skills and to move to more demanding labour markets. Thus, national protection of unskilled labour does not contribute to faster growth and productivity. It installs barriers to competition that would motivate labour and business to be more productive. Furthermore, even if domestic wages are higher than abroad, the labour component in the firms’ costs of production in advanced industries is low and no protection is needed for domestic industries to be competitive. Even if this is not the case, mutually advantageous trade based on competitive advantages can still take place and protection is not justified. Price sensitive advantages in international trade seem to be the most vulnerable to competition today. Firms and nations are gaining advantages in international competition based on sophisticated demand, technological improvements, and innovations. Trade restrictions tend to demotivate domestic labour and business to upgrade and integrate in the global economy, and increase their competitiveness. Thus, in the long run, trade restrictions that would preserve domestic jobs will contribute to competitive disadvantages and higher structural unemployment and backwardness of domestic industrial structures. The desire to reduce domestic unemployment. In addition to above mentioned arguments, the following reflections may be developed. In the short run, trade restrictions may save some domestic employment in internationally uncompetitive industries. Particularly, this argument holds for small countries whose markets and employment are threatened by large foreign companies. Thus, in the short run, trade restrictions may bring positive effects. However, such policies would bring to allocative inefficiencies in the national and global context. Opportunity costs of lower unemployment in this case tend to be higher than the cost of unrestricted imports. In terms of dynamic efficiency, the nation will not be motivated to increase productivity and competitiveness. The welfare effect will be positive in the short run but negative in the long run. Moreover, other nations will retaliate and as a result all countries lose. The need to counteract dumping in international trade. Dumping refers to selling in a foreign market at below the price charged domestically or elsewhere. It might be argued that just some of the cases when firms sell abroad at prices below the price charged domestically should be contend against. Basically, actions against dumping should be supported in cases when foreign producers try to hamper competition and discourage innovation and upgrading. Debates about such activities attracted attention during the Singapore meeting of the WTO in December 1996. Another type of dumping that should be prevented is the predatory dumping, when foreign firms are trying to drive domestic producers of a given good or service out of business, after which the price is increased. Such a conduct breaks antimonopoly legislation and is a subject to prosecution, though it is difficult to prove. Dumping can also appear when foreign firms try to enter and acquire positions at more competitive foreign markets without having to reduce domestic prices. In this case there is no need to create barriers even when foreign price is lower than the firms average cost. Entering highly competitive markets would encourage these companies to increase productivity and probably decrease domestic prices. Fighting against it will be an anticompetitive action. If dumping is persistent, domestic consumers benefit from the low prices for the imported goods and services. On the other hand, continuing lower prices will motivate domestic firms to upgrade and innovate in order to be competitive. Thus, an argument against this type of dumping can hardly be developed. The need to protect the infant industries. In this case, government tries to help new domestic industries to be established and grow until they become competitive internationally. This argument holds that domestic industries may have a potential for competitive advantages but they cannot be established and grow in the face of foreign competition. Therefore, until the industry has grown in size and efficiency it should be protected from foreign competition. Unfortunately, the eventual remove of restrictions proves to be highly difficult politically. Moreover, protection incurs cost and lost of welfare. Domestic consumers have to pay higher prices for the goods and services under consideration instead of buying cheaper foreign production. Anyway, if in the long run the returns to domestic industry are high enough to justify protection, national firms may create new jobs, higher efficiency and contribute significantly to the country’s economic growth and international competitiveness. Some economists argue that a direct subsidy to the infant industry is preferable because it will not distort domestic consumption and relative prices. Unfortunately, such a policy is hard to introduce and perform, because it involves additional cost instead of revenue generation through tariffs imposed to foreign firms. Protect industries important for national defence. This argument may be justified only on the political basis. From the economic point of view, the nation should be aware of the fact that other countries are likely to retaliate and, as a result, the opportunity cost of trade restrictions will rise. By excluding industries important for national defence from free international trade the nation would take the risk of uncompetitiveness not only in these fields but in related and supportive industries. The overall effect for the national defence may be negative. Decrease the national balance of payments deficit. Trade restrictions may help saving scarce foreign currency on shrinking imports and improve the current account balance. However, other nations may retaliate and newly created barriers for the national exports would seep out the advantages gained by import restrictions. On the other hand, if domestic demand for imports is highly inelastic, spending on imports will increase while the quantities bought fall. Thus, the overall effect for the national economy may be higher prices on imported goods that do not have substitutes, an increase in the price level, reduced purchasing power in the nation and worsened balance of payment. Improve the nation’s terms of trade and welfare. Restrictions on imports may improve the welfare in the short run by encouraging domestic production and employment in protected industries. On the other hand, the rest of the world is likely to retaliate and then, in the long run, export industries will be hurt. Thus, such beggar-thy-neighbour policies have a negative effect on national and international economy in the long run. Strategic trade policies. This argument for import restrictions is similar to the infant-industry argument. Trade restrictions are believed to protect emerging high tech industries exposed to high risks and oligopoly market structures in the world economy. Encouraging the growth such national industries may open opportunities to the nation successfully to compete big international companies and even to take advantage of oligopoly power and external economies. Unfortunately, strategic trade policies are difficult to carry out. The nation cannot prevent other countries to undertake the same policies picking the same high tech industries, and, thus, neutralizing the potential effect of the efforts. The scientific tariff. Imposing such a tariff on imports aims to make the price of the imported good equal to the price of the domestically produced good so as to enable domestic producers to compete with foreign rivals. This argument is wrong by definition because it would eliminate all national differences in relative prices and the very meaning of international trade. On the other hand, such an intervention in price mechanism creates distortions in relative prices, hence in rational and efficient use of scarce resources. The need to protect national health and safety standards. Imposing severe standards on imported goods may be justified from the point of view of preventing externalities and counteracting information asymmetry. Such policies are designed against functional market failures and should be carried out by nations if they are not designed just to create administrative barriers to imports.