Two Faces of Causality: A Small Case Study of the Admission of

advertisement

UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND

COLLEGE OF INFORMATION STUDIES

Two Faces of Causality: A Small Case Study of the Admission of

Scientific Evidence to Show Causality in a Bias and a Toxic Tort

Case in the 4th Circuit

Christina Kirk Pikas

LBSC 735: Legal Issues in Managing Information

Fall 2002

Due: December 11, 2002

Introduction

Over the past 10 years and many complaints of junk, voodoo, and bad science in court,

multiple efforts have been made to correct the way scientific evidence is handled in the federal

court system.1 Three significant Supreme Court rulings, new and revised federal rules of

evidence, and academic study have provided varied tools for triers of fact to employ to sort

through the evidence. First, the Daubert ruling in 1993 created a framework for trial judges to

use to evaluate the reliability, validity, and fit in accordance with the Federal Rules of Evidence.

Then, the Supreme Court ruled on two cases regarding the application of Daubert: Joiner

covered appeals and Kumho answered controversy about what types of expert testimony Daubert

covers.

The fourth circuit has heard about twenty-five cases in the past two years alone that hinged

on testimony included or excluded based on the Daubert criteria.2 These experts included

doctors, thermodynamics professors, maintenance supervisors, and several psychologists. The

judges are not expected to know all of these fields, but they must be able to assess the quality of

the evidence.

This paper reviews the efforts made to reform the handling of scientific evidence and several

areas of science and statistics that give judges the most difficulty: epidemiology, toxicology, and

multiple regression analysis. Specifically, this paper explores how the Daubert treatment of

scientific evidence influenced the resolution of two cases in the fourth circuit in which statistical

methods or scientific evidence were employed to show causality. Some of the scientific methods

used in court cases are discussed, causality is defined, and two diverse cases are studied in more

detail to demonstrate the application of the Daubert standards and statistical methods.

Background

Over the past century, scientific information has become more and more a part of the legal

system -- especially the civil tort system. Over this time, it has become clear that lawyers,

1

According to Robert Park in Voodoo Science: The Road from Foolishness to Fraud (New York: Oxford

University Press, 2000), 9, there are three types of Voodoo Science: pathological (scientists fool themselves), junk

(scientists craft arguments to fool or confuse), and pseudoscience (like magic and aliens – the language of science

without any actual science).

2

Peter Nordberg, “Fourth Circuit,” Daubert on the Web, November 20, 2002, available on the internet at

http://www.daubertontheweb.com/fourth_circuit.htm (accessed 11/21/02).

Pikas 2

judges, and juries for the most part do not have much science background and are therefore only

minimally able to determine good science from bad. This generated valid concerns that junk

science was winning large settlements. In addition to the increase in hard scientific evidence and

expert testimony in the courts, there is an increased introduction of social science, medical,

toxicological, and epidemiological experts and evidence. This information, too, relies on

complicated statistics and statistical methods. Some examples of cases relying on complicated

statistics dealt with employment discrimination, voter’s rights, product liability, census counting,

and patent infringement damages.

A series of decisions and rules since 1923 have combined to redefine the role of the judge as

gatekeeper and to define what considerations she must make prior to admitting scientific

evidence. The first of these decisions came from the Frye murder trial.

Frye

The first ruling that set a standard for admitting scientific evidence was the Frye decision in

1923. The discussion was over the admission of an early precursor to the lie detector test. Prior

to this ruling, experts were allowed to testify if they had knowledge beyond that of the average

juror and expertise was assumed if the expert was commercially successful in the field.3 The key

statement is

while courts will go a long way in admitting expert testimony deduced from a

well-recognized scientific principle or discovery, the thing from which the

deduction is made must be sufficiently established to have gained general

acceptance in the particular field in which it belongs.4

There are strengths and weaknesses to this approach. First, it places the responsibility for

ensuring good science back in the hands of the scientists perhaps best able to judge the

methodology and findings. Second, this criteria is fairly simple to apply and can be applied

without learning the relevant background material. Detractors point out that this excludes all

novel science and that general acceptance is less common in “rigorous fields with the healthiest

scientific discourse.”5

3

David L Faigman, David H. Kaye, and Michael J. Saks, "New Directions in Expert Testimony: Scientific,

Technical, and Other Specialized Knowledge Evidence in Federal and State Courts," American Law Institute American Bar Association Continuing Legal Education ALI-ABA Course of Study, April 26, 2001, Available via

Westlaw at http://www.lawschool.westlaw.com. (accessed 12/5/2002), §1-2.1

4

Daubert v Merrill54 App. C. C., at 47, 293 F., at 1014 as quoted in Kenneth R. Foster and Peter W.

Huber, Judging Science: Scientific Knowledge and the Federal Courts ( Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 1997), 280.

5

Faigman, Kaye, and Saks §1-2.4.

Pikas 3

Daubert

The Daubert case, William Daubert, et al. v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (509 U.S.

579, 1993), involved the charge that the Merrell Dow product Benedictin was a human teratogen

responsible for the plaintiffs’ birth defects.6 Both sides submitted scientific evidence. The

plaintiff’s experts did a meta-analysis on published studies and also produced toxicological

evidence of the effect of large doses in laboratory animals. The defendant produced

epidemiological studies. The toxicological information was not admitted because the court

stated that only epidemiological studies showed causation. The judge did not admit the metaanalysis he because determined that it was not a “generally accepted” method and the specific

analysis had not received peer review.7

Certiorari was granted because of disagreements between courts “regarding the proper

standard for the admission of expert testimony.”8 Fifty years after the Frye decision discussed

above, the Federal Judicial Center issued the first edition of the Federal Rules of Evidence.

While very general, these provided general guidelines for admitting testimony and evidence.

Specifically, Rule 702, Testimony by Experts, allows testimony by a witness qualified as an

expert by “knowledge, skill, experience, training, or education” if the testimony will help the

court understand the evidence or determine a fact.9 Some courts in this time period applied the

Frye rule and others the rules of evidence.

Many amicus briefs were written including ones from the federal government, commercial

associations, legal foundations, and interested scientists, doctors, and researchers.10 One group

argued that junk science could lead to inappropriate liability others argued in turn that judges,

juries, and scientists do not understand scientific testimony and can’t be responsible for

determining its validity.11

6

See Foster and Huber , 277, for a reprint of the opinion.

7

Ibid, 278.

8

Ibid, 279.

9

Federal Rules of Evidence, 2001, http://www2.law.cornell.edu/cgibin/foliocgi.exe/fre/query=[jump!3A!27rule103!27]/doc/{t212}?, (12/4/2002), Rule 702.

Howard H. Kaufman, “The Expert Witness. Neither Frey [sic] nor Daubert Solved the Problem. What

Can Be Done?” International Review of Law Computers & Technology v15 n1 (March 2001), available via EBSCO

MasterFile Premier at http://www.sailor.lib.md.us/cgi-bin/ebsco, (accessed 10/15/2002), 87-8

10

11

Ibid, 88.

Pikas 4

The Daubert decision ushered in a new era in scientific evidence because it codified the role

of the judge as gatekeeper in lieu of other scientists. The assumption was that the judge is better

able to assess the reliability, validity, and helpfulness of scientific evidence than the jury and so

should review the scientific evidence in pre-trial hearings and admit only the experts and

evidence that might meet the following flexible guidelines:

1.

2.

3.

4.

whether it can be (and has been) tested

whether it has been subjected to peer review and publication

the known or potential rate of error

the existence and maintenance of standards controlling the

technique’s operation

5. general acceptance12

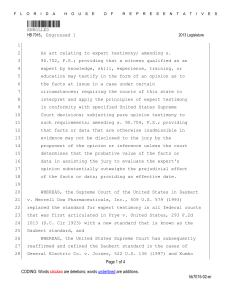

Joiner and Kumho

Soon after Daubert the Supreme court agreed to hear a case to determine the standard for an

appellate court to apply in reviewing a district court’s Daubert decision.13 In General Electric

Co. v. Joiner14 the plaintiff was a smoker with a history of cancer in his family. At his

workplace, he was exposed to PCBs that he claimed led to his cancer. The trial court excluded

the plaintiff’s experts after applying the Daubert criteria and granted a summary judgment for

the defendant. The Supreme Court reviewed the evidence and affirmed that the evidence was

properly excluded. The important results were first that abuse of discretion is what the appeals

court should examine in Daubert cases and second that the focus should be on the methodology

not the conclusions, which could conflict. According to Park in his book on Voodoo Science,

Joiner strengthened Daubert by making it so that “not only must evidence be obtained by

scientifically valid procedures, it must also be scientifically interpreted.”15

In the four years immediately following Daubert, controversy developed over exactly what

evidence the ruling covers. In Kumho Tire v. Carmichael,16 the plaintiff sued the tire company

for product liability because a blown minivan tire caused an accident in which there was a

fatality. The Supreme Court held that the gatekeeping requirement extends to all expert

12

Foster and Huber, 284-5.

13

Margaret A. Berger, “The Supreme Court’s Trilogy on the Admissibility of Expert Testimony,” chapter

in Federal Judicial Center, Reference Manual on Scientific Evidence, 2d ed, (St. Paul, MN: West Group, 2000), 13.

14

522 U.S.136-7, 1997.

15

Park, 170.

16

119 S. Ct. 1167, 1999.

Pikas 5

testimony including engineering, psychology, economics, etc. Additionally, no difference is

noted for the expert who relies on book science and one who relies on skills or experience. The

Daubert factors are to be applied flexibly, not all will apply to every situation.

Causality

Toxic Torts and Product Liability

In civil cases, especially toxic torts and product liability cases, the primary reason for the

introduction of an expert or scientific evidence is to prove causality. In other words, the plaintiff

introduces an expert to provide evidence that the defendant’s actions, products, etc., actually

caused the harm to the plaintiff.17 In civil torts relating to property damage caused by an

accident, this evidence is obtained easily. A witness testifies that he saw the accident and there

are pictures of the defendant’s car in the plaintiff’s living room. In toxic torts, on the other hand,

there is no direct evidence that the chemicals resulted in the injury. Likewise, in discrimination

cases there is no simple chain of events or consensus of the end state.

Proving causality is very complicated. In most of the toxic torts, no one really knows if a

given chemical, in a given quantity over a certain time actually caused the harm. Statistics in

conjunction with epidemiology and toxicology make it more or less likely but do not fully prove

the causality. First, the plaintiff has to prove general causality (“is the agent capable of causing

disease?”). 18 In other words, have scientifically valid and reliable studies shown the chemical

more often than not leads to the condition exhibited by the plaintiff? Then the plaintiff has to

prove specific causality (in this case, did the agent cause this particular harm?)

The two major fields used to show causality in toxic torts are epidemiology and toxicology.

Epidemiology is the study of “incidence, distribution, and etiology of disease in human

populations.”19 Controlled randomized trials are preferred because confounding factors and

errors can be minimized; however, since it is unethical to knowingly expose subjects to harm,

most epidemiological studies are observational in nature. Epidemiologists monitor groups over

time who have been exposed to the agent and similar groups who have not been exposed. Error

17

Per Bryan A. Garner, ed., Black's Law Dictionary, 7th ed., (St. Paul, MN: West Group, 1999), 213, to

cause is “to bring about or effect.”

Michael D. Green, D. Michael Freedman, and Leon Gordis, “Reference Guide of Epidemiology,” chapter

in Federal Judicial Center, Reference Manual on Scientific Evidence. 2d ed. (St. Paul, MN: West Group, 2000),

336.

18

19

Ibid, 335.

Pikas 6

occurs as a result of confounding factors, sample error, information bias, and statistical

problems.20 Even in the absence of the errors above, researchers are reluctant to infer causality

but apply the following factors to make a decision:

temporal relationship

strength of the association

doses-response relationship

replication of the findings

biological plausibility (coherence with existing knowledge)

consideration of alternative explanations

cessation of exposure

specificity of the association

consistency with other knowledge.21

Toxicology employs different principles to study the effects of foreign agents on the human

body. Per Goldstein and Henifin in the “Reference Guide on Toxicology,” there are three main

tenets of toxicology: all substances are hazardous to humans depending on dose, each agent

produces a “specific pattern of biological effects that can be used to establish disease causation,”

and the effects on laboratory animals are useful predictors of the effect on humans.22 The results

of toxicological studies are risk assessments and expected effects of given doses of agents. Per

Erica Beecher-Monas, courts are reluctant to accept toxicology studies on animals even though

they are well accepted in the scientific realm and a key problem is that most “animal toxicity

studies are not designed to demonstrate causation but to identify biological mechanisms of

toxicity.”23 The Reference Guide suggests the following criteria to judge specific causal

association between the agent and the plaintiff’s disease:

Was the plaintiff exposed to the substance so that the substance was

absorbed into the body?

Were there other factors present that affected the distribution within the

body?

What is known about the relationship between human metabolism and the

compound?

20

See Darrell Huff, How To Lie With Statistics (New York: Norton, 1982) chp. 1, for a discussion of

sample error and information bias (what subjects report).

21

Quoted from Green, Freedman, and Gordis, 375.

22

Bernard D. Goldstein and Mary Sue Henifin, “Reference Guide on Toxicology,” chapter in Federal

Judicial Center, Reference Manual on Scientific Evidence. 2d ed. (St. Paul, MN: West Group, 2000), 403.

23

Erica Beecher-Monas, "A Ray of Light For Judges Blinded By Science: Triers of Science and

Intellectual Due Process," Georgia Law Review v33 (Summer 1999): n12. Available via Lexis on the internet at

http://www.lexis.com. (accessed 12/7/2002).

Pikas 7

What excretory route does the compound take and how does this affect its

toxicity?

What was the temporal relationship?

Was the exposure at or above the known threshold level?24

Discrimination and Bias

Statistical methods originally developed to study physical phenomena in the hard sciences

are now commonly applied to the social sciences. Legendre and Gauss originally developed

regression methods in the early 1800s to fit astronomical data about the orbits of planets.25 The

scientists carefully measured and knew the errors in their equipment and models. In the social

sciences, the models tend to be somewhat arbitrary and the inclusion or omission of variables is

not always clearly reasoned. In fact, Klock suggests that social scientists sometimes go

relationship shopping—they run statistical tests using the same data with multiple hypotheses

and equations. Whichever fits best must explain the effect.26

In discrimination and cases as applied to hiring, admission, voter redistricting, or census

taking a statistical technique known as multiple regression is used to prove causality and extent.

In other words, the analysis is used to prove that one group was treated unfairly specifically due

to one and only one factor, their age, sex, ethnicity, etc. A multiple regression model is used to

control for variables not related to the factor being tested. An example from the Reference

Manual on Scientific Evidence is of a company trying to determine if there is sex discrimination

in employee salaries. To predict salaries (independent variable) three explanatory variables are

used: experience, education, and a dummy variable (stands for sex, can be either 0 or 1). The

researcher plugs the data into the equation and determines the coefficient for each variable. The

coefficient for the dummy variable should show the variation of the salary between genders.27

Once the multiple regression analysis is complete there are several methods employed to

determine if it is an appropriate model and if the results are practically and statistically

24

Goldstein and Henifin, 422-6.

D. A. Freedman, “From Association to Causation: Some Remarks on the History of Statistics.”

Statistical Science v14 i3 (Aug 1999): 247.

25

26

Mark Klock, “Finding Random Coincidences While Searching For The Holy Writ of Truth:

Specification Searches In Law And Public Policy or Cum Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc?” Wisconsin Law Review i4

(2001), available via Westlaw at http://www.lawschool.westlaw.com, (accessed 11/30/2002), 1010-1.

27

David H. Kaye and David A. Freedman, “Reference Guide on Statistics,” chapter in Federal Judicial

Center, Reference Manual on Scientific Evidence, 2d ed, (St. Paul, MN: West Group, 2000), 145-8.

Pikas 8

significant.28 A first measure to determine if outlying data points are affecting the fit is the

standard deviation for each of the variables. This measures the bell curve in which the majority

should fall; any more than one standard deviation away is noted. For example, if the salary

difference attributed to gender is $1,500 and the standard deviation is $1,600, the difference is

not significant and probably occurred by chance. A next measure is goodness of fit. Two related

calculations should be performed: standard error of regression (standard deviation of the

regression error) and R² (“the percentage of variation in the dependent variable that is accounted

for by all the explanatory variables”).29

Case 1: Nettles v. Proctor & Gamble

The case of Susan Q. Nettles v. Proctor & Gamble Manufacturing Company (33 Fed. Appx.

670; 2002 U.S. App. LEXIS 6953)30 illustrates the principles of causality and the application of

the Daubert trilogy rulings. Ms. Nettles alleged that Proctor & Gamble’s (P&G) Vicks Sinex

Nasal Spray caused her blindness. Specifically, she alleged that the primary ingredient,

oxymetazoline, caused anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Her case was based on the expert

testimony of a neuro-opthalmologist.

The appeals court determined first that the district court had correctly applied the Daubert

criteria. In pre-trial hearings, the court analyzed the “reasoning and methodology underlying

[the expert’s] opinions.”31 The court determined that there were no toxicological or

epidemiological peer-reviewed articles associating the main ingredient with the plaintiff’s

blindness. Additionally, the court considered the plaintiff’s exposure to the product and stated

that it was minimal (dose-relationship test). The court did not take into account any

toxicological studies or other Daubert factors like testing or general acceptance. The plaintiff’s

only evidence was a temporal connection; therefore the statement in the opinion: “the medical

causation expert has ‘inferred causation’ from a situation-specific occurrence.”32

28

See Foster and Huber chapter 4 (69-109) for a general discussion of errors and Huff chapter 4 (53-9) for

a discussion of significance of error.

29

Rubinfeld, 212-5.

30

Available via Lexis on the internet at http://www.lexis.com. (accessed 9/24/2002).

31

Ibid, opinion.

32

Ibid.

Pikas 9

The court of appeals also cited the Kumho and Joiner decisions in this opinion. First, the

court stated that the lower court acted with sound discretion as required by Joiner and was not

capricious or arbitrary. Furthermore, the appeals court stated that the decision was not an abuse

of discretion as defined in Kumho. The defendant moved for a summary judgment and one was

granted. The appeals court affirmed the decision.

The Nettles decision is a good example of the concepts of the paper. Daubert was correctly

applied: the guidance is flexible so that courts may use a subset of the guidelines as appropriate

to the case. The Kumho and Joiner decisions were applied by the appeals court correctly to

reinforce the lower court’s application of Daubert. The plaintiff’s expert did not, in fact,

produce enough research or evidence to back up the claim.

Case 2: Smith, Degenaro, Belloni, Rimler, Rosenbaum, On behalf of

themselves and all others similarly situated v. Virginia Commonwealth

University

The case of Ted J. Smith, III; Guy J. Degenaro; Frank Belloni; George W. Rimler; Allan

Rosenbaum, On behalf of themselves and all others similarly situated v. Virginia Commonwealth

University (VCU) (84 F.3d 672)33 asks the question whether VCU’s effort to correct past sex

discrimination in pay was in error and trammeled the rights of the male professors. This case

demonstrates the difficulties of using multiple regression techniques to show causality in bias

cases and the potential benefit of applying Daubert criteria to the plaintiff’s expert testimony.

In the late 1980’s the VCU school newspaper printed the salaries of the professors. When

the professors studied these, they noticed that the male professors made more than the female

professors in the same position did. The administration formed a committee to study the

situation. Based on previous studies done at area universities, the committee decided to do a

multiple regression study to determine if there was a pay differential and if so, how much.

Without taking into account any other variables, the male professors’ pay was $10,000 more per

year than the female professors’ was. The multiple regression study controlled for national

salary average, degree, tenure, quick tenure, years of experience at VCU, academic experience,

experience as department chair, and gender.

33

Available via Westlaw on the internet at http://lawschool.westlaw.com, (accessed 11/11/2002).

Pikas 10

The multiple regression study showed a $1,354 pay difference between the genders. After

some time and a recalculation, administration constituted a committee to give salary increases to

qualified female professors. The female professors provided documentation to the committee

and received raises from 1-40% depending on the disparity in pay. No male professors were

permitted to request a review and increase.

The plaintiffs allege that the multiple regression analysis was faulty because it failed to take

into account major factors affecting pay, e.g., performance and prior administrator experience.

The appeals court noted that the VCU compensation system was based on merit. The annual

reviews consider teaching load, teaching quality, publications, research, and service to the

community. The department chair recommends salary increases to the dean who awards the

raise. According to the opinion, “salaries vary widely from department to department.”34

The district court granted the defendant’s request for a summary judgment based on the

belief that VCU did a thorough study and included all variables necessary for the multiple

regression analysis, the money was handed out fairly and on a individual basis, and this action

was completed to correct a previous inequity. The VCU statisticians contended that performance

factors were “inherently subjective and unquantifiable” and substituted the rough proxies of

tenure and experience.35

Because the original case was decided only months after Daubert, it is not surprising that the

district court judge did not use the factors to assess the admissibility of the scientific evidence.

The lower court judge mentioned in the opinion that published studies existed (no mention of

peer review) and that the form of analysis was generally accepted. 36 He appeared to approve of

the use of performance factors only in the remedy mechanism as other universities did. The

VCU statisticians assumed that performance factors were similar across the groups.

The dissenting judges in the appeals court did apply Daubert. They stated that the

assumptions made by the plaintiff’s expert were not backed by research and were “speculative;”

furthermore, that the Kent State study mentioned by the expert is very different from the VCU

study so does not provide a “scintilla of evidence” as required by Daubert.

34

Ibid, 675.

35

Ibid, 682.

36

Smith, et al. v. Virginia Commonwealth University (856 F. Supp. 1088; 1994 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 9277),

July 8, 1994, available via Lexis at http://www.lexis.com, (accessed 12/7/2002), n15.

Pikas 11

A careful application of the Daubert standards by the lower court may have cleared up the

primary issue, the inclusion of performance factors in the multiple regression analysis.

Specifically, both the plaintiff’s and the defendant’s experts should have provided error analysis

and some calculations to show that the gender differences were practically and statistically

significant based on the error of the study and the pay of the professors. If the plaintiff’s expert

had shown the actual impact of the performance factors or the impact of the administrator pay,

the case would have been more convincing. Without this information, the plaintiff’s expert did

not prove that the factors should be included and the summary judgment was justified.

Additionally, had Joiner been decided when this came to the appeals court, the appeals court

may have been convinced to affirm the summary judgment as the opinion was not capricious or

arbitrary but carefully reasoned.

As to the use of multiple regression analysis to decide this matter, it seems that the model

inadequately fit the situation. The intention of the analysis was to determine the impact gender

had on salary. A complete analysis would set the salary as the dependent variable, and all of the

other factors related to pay as explanatory variables with the addition of a dummy variable for

sex. Checks should show that the explanatory variables are not correlated. Other analysis

should examine error and fit.37 The variables selected by the VCU statisticians were convenient

and easily quantified, but did not adequately fit the actual situation or measure the factors

impacting the salary.

In sum, the legal issues and lack of support would lead to the summary judgment for the

defendants. If properly supported and adequately argued, however, the case should have yielded

a summary judgment for the plaintiff as suggested by Judge Luttig in his concurring opinion

because the initial analysis did not paint an accurate picture of the salary situation at VCU.38 In

other words, the equation used for the multiple regression analysis should have modeled the real

situation at the time of calculation; however, none of the explanatory variables described the

actual factors that determined the salary. The initial analysis was invalid.

Daniel L. Rubinfeld. “Reference Guide on Multiple Regression,” chapter in Federal Judicial Center,

Reference Manual on Scientific Evidence, 2d ed, (St. Paul, MN: West Group, 2000), 194-200.

37

38

Smith, Degenaro, Belloni, Rimler, Rosenbaum v. VCU, 681.

Pikas 12

Conclusion

The definition of cause is simple: to bring about or effect; yet, in civil cases where causality

is all-important, there are many definitions and ways to prove legal causality. In product liability

cases, the common way is to have an expert testify. However, if the plaintiff’s entire case rests

on an expert deemed unreliable or irrelevant by the judge, the case will never reach a jury and

will end by summary judgment. In discrimination and bias cases, the courts show much more

caution and less accuracy39, but still cases end in summary judgments.

Cases are becoming more complex, each involving several types of scientific evidence and

statistical analyses. Unfortunately, this can lead juries to commingle evidence, using “evidence

of one element of a legal claim to substitute for proof of another element.”40 This makes it

imperative for judges to serve as gatekeeper to review and strain out invalid, unreliable, or

irrelevant evidence prior to the start of the trial.

In the post-Daubert era where the judge sees the evidence at least 90 days prior to the trial

and decides on its merits before jury selection, the majority of the responsibility is on the judge

to understand complicated statistical analyses or scientific evidence. Her purpose is not to

decide what is the correct conclusion or which science best describes the real world, but to

determine if the evidence is scientifically valid, reliable, and applies to the case at hand.

Courses, studies, and books to assist the trier of fact in understanding these pieces of evidence

abound; but recent studies show that although judges agree with the gatekeeper role, they do not

necessarily understand the Daubert criteria.41 Justice Breyer, in his introduction to the Reference

Manual on Scientific Evidence, suggests judges employ neutral experts to help sift through the

evidence.42 This seems like a beneficial approach for all but the taxpayers who foot the high

bills.

Beecher-Monas suggests “Probabilistic attribution and statistical analysis frequently confound the

courts,” 1069.

39

40

Kaufman, 82.

41

Shirley A. Dobbin, Sophia I. Gatowski, James T. Richardson, Gerald P. Ginsburg, Mara L. Merline, and

Veronica Dahir, “Applying Daubert –How Well Do Judges Understand Science And Scientific Method?”

Judicature v85 i5 (Mar-Apr 2002): 244-7, available via Westlaw at http://www.lawschool.westlaw.com, (accessed

11/30/2002), 246-7.

42

Stephen Breyer, “Introduction,” chapter in Federal Judicial Center, Reference Manual on Scientific

Evidence, 2d ed, (St. Paul, MN: West Group, 2000), 7.

Pikas 13

We have seen here from the application of the Daubert factors to the sample fourth circuit

cases that the factors appear to aid in understanding the cases and coming to a just resolution in

the Nettles case. Likewise, the lack of the Daubert framework in the VCU case added confusion

and disguised the central issue of the validity of the original statistical analysis. Overall,

although not flawless, the Daubert framework with the Joiner and Kumho enhancements seems

to be a useful tool for judges to evaluate the merits of expert testimony. More training for the

judges would not be as helpful as the increase in use of neutral experts to help sort through the

evidence.

Pikas 14

Bibliography

Beecher-Monas, Erica. "A Ray of Light for Judges Blinded by Science: Triers of Science and

Intellectual Due Process." Georgia Law Review v33 (Summer 1999): 1047-111.

Dixon, Lloyd and Brian Gill. Changes in the Standards for Admitting Expert Evidence in

Federal Civil Cases Since the Daubert Decision. Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2001.

Dixon, Lloyd and Brian Gill. “Changes in the Standards for Admitting Expert Evidence in

Federal Civil Cases Since the Daubert Decision.” Psychology, Public Policy, & Law v8

i3 (September 2002): 251-308. Available via Westlaw at

http://www.lawschool.westlaw.com. (accessed 11/30/2002).

Dobbin, Shirley A., Sophia I. Gatowski, James T. Richardson, Gerald P. Ginsburg, Mara L.

Merline, and Veronica Dahir. “Applying Daubert –How Well Do Judges Understand

Science And Scientific Method?” Judicature v85 i5 (Mar-Apr 2002): 244-7. Available

via Westlaw at http://www.lawschool.westlaw.com. (accessed 11/30/2002).

Faigman, David L. Legal Alchemy: The Use and Misuse of Science and the Law. New York:

W. H. Freeman, 1999.

Faigman, David L., David H. Kaye, and Michael J. Saks. "New Directions in Expert Testimony:

Scientific, Technical, and Other Specialized Knowledge Evidence in Federal and State

Courts." American Law Institute - American Bar Association Continuing Legal

Education ALI-ABA Course of Study. April 26, 2001. Available via Westlaw at

http://www.lawschool.westlaw.com. (accessed 12/5/2002).

Federal Judicial Center. Reference Manual on Scientific Evidence. 2d ed. St. Paul, MN: West

Group, 2000.

Federal Rules of Evidence. 2001. Available on the internet from the Legal Information Institute

at http://www.law.cornell.edu/rules/fre/overview.html. (accessed 12/4/2002).

Foster, Kenneth R. and Peter W. Huber. Judging Science: Scientific Knowledge and the Federal

Courts. Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 1997.

Freedman, D. A. “From Association to Causation: Some Remarks on the History of Statistics.”

Statistical Science v14 i3 (Aug 1999): 243–58.

Garner, Bryan A., ed. Black's Law Dictionary. 7th ed. St. Paul, MN: West Group, 1999.

Huber, Peter W. Galileo’s Revenge: Junk Science in the Courtroom. Basic Books: 1991.

Huff, Darrell. How To Lie With Statistics. New York: Norton, 1982.

Jasanoff, Sheila. Science at the Bar: Law, Science, and Technology in America. Cambridge,

MA: Harvard University Press, 1995.

Johnson, Molly Treadway, Carol Krafka, and Joe S. Cecil. Expert Testimony in Federal Civil

Trials: A Preliminary Analysis. Washington: Federal Judicial Center, 2000.

Jones, Gregory Todd and Reidar Hagtvedt. "Sample Data as Evidence: Meeting the

Requirements of Daubert and the Recently Amended Federal Rules of Evidence."

Georgia State University Law Review v18 (Spring 2002): 721-48. Available via LEXIS

at http://www.lexis.com. (accessed 12/7/2002).

Pikas 15

Kaufman, Howard H. “The Expert Witness. Neither Frey [sic] nor Daubert Solved the Problem.

What Can Be Done?” International Review of Law Computers & Technology v15 n1

(March 2001): 79-101. Available via EBSCO MasterFile Premier at

http://www.sailor.lib.md.us/cgi-bin/ebsco. (accessed 10/15/2002).

Kaye, D H. “The Dynamics of Daubert: Methodology, Conclusions, and Fit in Statistical and

Econometric Studies.” Virginia Law Review v87 i8 (Dec 2001): 1933-2018. Available

via Westlaw at http://www.lawschool.westlaw.com. (accessed 11/30/2002).

Klock, Mark. “Finding Random Coincindences While Searching For The Holy Writ of Truth:

Specification Searches In Law And Public Policy or Cum Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc?”

Wisconsin Law Review i4 (2001): 1007-65. Available via Westlaw at

http://www.lawschool.westlaw.com. (accessed 11/30/2002).

Kovera, M B, M B Russano, and B D McAuliff. “Assessment of the Commonsense Psychology

Underlying Daubert – Legal Decision Makers’ abilities to Evaluate Expert Evidence in

Hostile Work Environment Cases.” Psychology, Public Policy, & Law v8 i2 (Jun 2002):

180-200. Available via Westlaw at http://www.lawschool.westlaw.com. (accessed

11/30/2002).

Krafka, Carol, Meghan A. Dunn, Molly Treadway Johnson, Joe S. Cecil, Dean Miletich. “Judge

and Attorney Experiences, Practices, and Concerns Regarding Expert Testimony in

Federal Civil Trials.” Psychology, Public Policy, and Law v8 n3 (September 2002):

309-32.

Nordberg, Peter. “Fourth Circuit.” Daubert on the Web. November 20, 2002. Available on the

internet at http://www.daubertontheweb.com/fourth_circuit.htm . (accessed 11/21/02).

Park, Robert. Voodoo Science: The Road from Foolishness to Fraud. New York: Oxford

University Press, 2000.

Sanders, Joseph, Shari S. Diamond, and Neil Vidmar. “Legal Perceptions of Science and Expert

Knowledge.” Psychology, Public Policy and Law v139 n8 (Jun 2002): 139-153.

Available via LEXIS at http://www.lexis.com. (accessed 10/8/2002).

Thomas, William A., ed. Scientists in the Legal System. Ann Arbor, MI: Ann Arbor Science,

1974.

Worthington, D L, M J Stallard, J M Price, and Pj Goss. “Hindsight Bias, Daubert, and The

Silicone Breast Implant Litigation – Making The Case For Court-Appointed Experts In

Complex Medical And Scientific Litigation.” Psychology, Public Policy, & Law v8 i2

(Jun 2002): 154-79. Available via Westlaw at http://www.lawschool.westlaw.com.

(accessed 11/30/2002).

Pikas 16