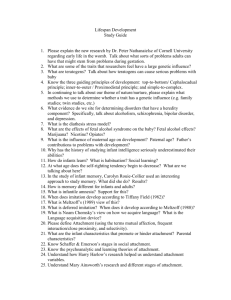

Touch_scale referenc..

advertisement