Butterflies - Oxford 1st Grade

advertisement

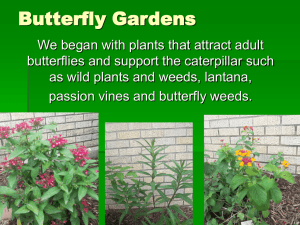

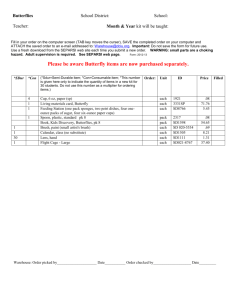

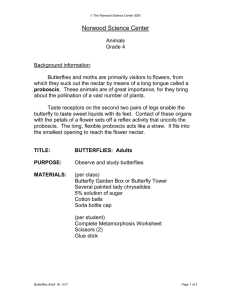

Butterflies - Suggested Materials Books/Videos: Life-cycles theme unit - Newbridge Educational Publishing The Magic School Bus Butterflies - Scholastic Videos Eyewitness Books - Butterfly and Moth Eyewitness Juniors - Amazing Butterflies and Moths Eyewitness Videos - Butterfly and Moth Monarch Butterfly of Aster Way (book and tape) The Butterfly Metamorphoses Book (accordion book) The Very Hungry Caterpillar Book From Caterpillar to Butterfly Book Models: Butterfly Metamorphosis plastic models (caterpillar, pupa, butterfly, moth) EVA Foam Models Butterfly metamorphosis Butterfly Mobile Posters: Butterflies Poster Beckley Cardy Supply Butterfly Alphabet Poster thenaturestore.com Butterfly Poster AllPosters.com Moth Lifecycle Poster thenaturestore.com Monarch Lifecycle Poster thenaturestore.com Miscellaneous: The Butterfly Nursery The Very Hungry Caterpillar Floor Puzzle Hand and Finger Puppets Butterfly Metamorphosis Floor Puzzle Butterfly and Moth Unit Prepared for Oxford School District 1st Grade by Carol Cleveland Emily Atchley Jon Wilson NMGK-12 Fellows (2000-2001) Objectives: This unit is designed to introduce the concepts of species diversity, lifecycles, and scientific processes to students at a 1st grade level. All activities use butterflies as a focal point. Grade Level: 1st grade - Activities are geared to incorporate the life-science frameworks for Oxford School District, Oxford, MS. This unit is designed to fit into the spring curriculum. Table of Contents Background Information General Facts Differences between Butterflies and Moths Lepidopteran Life-Cycle Defense from Predation Poison Camouflage Eyespots Hiding Mimicry Bad Smells More Defense Monarch Migration Fall Migration Overwintering Sites Spring Migration Interesting Facts about Butterflies and Moths Extremes Size Butterfly Migrations Variety / Diversity Speed Development Time Behavior Drunk Fighting Strange Food Symbiosis Marking Houses Underwater Life Caterpillar Movement Avoiding Danger Licking Stones Lesson Plans Lesson 1: Introduction to Lepidopterans by Observing Butterfly and Moth Diversity Lesson 2: Butterfly and Moth Life-Cycle Introduction Lesson 3: Growing Butterflies to Observe Their Life-Cycle Lesson 4: Butterfly Coloration Lesson 5: Butterfly Migrations Lesson 6: Butterfly and Moth Wrap-Up Appendices A. Butterfly Worksheets: math, mazes, matching, color-by-number B. Butterfly Activities: games, poems, songs C. Arts and Crafts D. Recipes E. Coloring Pages Background Information for Teacher General Facts: (modified from: http://www.milkweedcafe.com/fascfacts.html) Butterflies and moths are in the Insect order Lepidoptera (scale wing). All Lepidopterans have a complete life-cycle that includes the following four stages: egg, larva, pupa, adult. Butterfly and moth wings are actually transparent. Iridescent scales overlap like shingles on a roof and give the wings the colors that we see. Contrary to popular belief, many butterflies can be held gently by the wings without harming the butterfly. Butterflies have taste sensors that are located in their feet, and by standing on their food, they can taste it. All butterflies, moths and their larvae (caterpillars) have six legs. Butterflies don't have mouths that allow them to bite or chew. They have a long, straw-like structure called a proboscis which they use to drink nectar and juices. When not in use, the proboscis coils like a garden hose. The proboscis is in two pieces and has a forked appearance. As soon as it emerges from the chrysalis, the butterfly begins working on the proboscis to form it into a tube. Some moths, like the Luna moth don't have a proboscis. Their adult lifespan is very short, and they do not eat. The Asian Vampire moth has a strong, sharp proboscis that can pierce skin and they drink the blood of animals. A caterpillar grows to about 27,000 times the size it was when it first emerged from its egg. If a human baby weighed 9 pounds at birth and grew at the same rate as a caterpillar, it would weigh 243,000 pounds when fully grown. Because the caterpillar's skin doesn't grow along with it as ours does, the caterpillar must periodically shed the skin (molt) as it becomes too tight. Most caterpillars molt five times before entering the pupa stage Butterfly caterpillars do not spin a cocoon. Moth caterpillars do spin cocoons of silken threads, often using leaves to help surround themselves. Butterfly caterpillars shed their final skin to reveal a pupa. The outer skin of this pupa hardens to form a chrysalis which protects and hides the transformation that is occurring inside. Pupae take on a wide variety of appearances, depending on the species of butterfly. Some hang from beneath leaves or twigs. Others are girdled to the side of a stem much like a worker on a telephone pole. Some are smooth and shiny while others are rough and even spiky. Some are beautifully colored with dots and lines of gold while others are drab and barely noticeable. No matter what the design, the function is the same - to lessen the chances of being eaten by a predator and to increase the likelihood of producing an adult butterfly or moth. Differences Between Butterflies and Moths: (from: http://www.butterflies-moths.com/) 1. Butterflies have always knobbed antennae, the antennae of moths are quite variable but never knobbed (often feathery) 2. Butterflies fly during the day, moths fly during the night 3. Butterflies rest with their wings vertically clapped above their bodies, moths rest with theirs horizontally on their bodies 4. Butterflies have less hairy bodies than moths 5. Butterflies do not have tiny hooks or bristles which link forewing to hindwing (moths do) Lepidopteran Life-Cycle (modified from: http://www.butterflies-moths.com/) Butterflies and moths belong to the group of insects with a complete metamorphosis or life-cycle. This means that there is a pupal stage and that the immature butterfly or moth is morphologically different from an adult butterfly or moth. Like all organisms who reproduce sexually, a butterfly's life begins with the fusion of an egg with a sperm. Female butterflies can store male sperm and from this reserve the female fertilizes the eggs one by one. After the eggs have been fertilized the female has to find a place to lay them. This place has to be safe for the egg and should provide enough food for the young caterpillar to develop. The larval stage is actually the growth stage of the life-cycle. Often the first meal of a caterpillar is the eggshell. Even though caterpillars may look quite different they all share one important feature: the ability to molt. Both the head of a caterpillar and its skin are made of elastic chitin and contains stretch receptors. If the skin is maximally stretched, these receptors submit a signal to the brain. The brain ensures that the molting hormone ecdyson and a juvenile hormone are present in the bloodstream. If both these hormones are available the new skin will be a caterpillar skin, if just ecdyson is available in the bloodstream, the new skin will be a pupal skin. The last molt of a caterpillar is quite spectacular, the new skin is not another caterpillar-skin but a pupalskin. Caterpillars eat mostly leaves of flowering plants and trees using jaws. Often they are dependent on only one species of plant (eg: Monarchs and Milkweed). The pupa is the metamorphic bridge between caterpillar and adult butterfly. Often the chrysalis is erroneously called the resting stage of the metamorphosis. Nothing could be further from the truth: larval characteristics are dismantled chemically and embryonic cells divide. Just a few hours after pupation adult characteristics begin to form; tiny wings, mouthparts, flying muscles and legs. Once the development of the butterfly is completed, the butterfly forces itself out the pupa. The new butterfly starts pumping fluid into its wings to expand them and when the wings are completely expanded they harden. Defense from Predation (modified from: http://www.enchantedlearning.com/subjects/butterfly/allabout/Defense.shtml) Butterflies are fragile and almost defenseless creatures. They rely on a variety of strategies to protect them from hungry predators. Their predators include birds, spiders, reptiles, other insects (e.g., wasps, flies, and mites), and small mammals. Caterpillars are soft bodied and slow moving. This makes them easy prey for predators, like birds, wasps, and mammals to mention just a few. Some caterpillars are even eaten by their fellow caterpillars (like Zebra swallowtail larva which are cannibalistic). In order to protect themselves from predators, caterpillars and butterflies use different strategies, including: Poison Some caterpillars are poisonous to predators. These caterpillars get their toxicity from the plants they eat. Generally, the brightly colored larva are poisonous; their color is a reminder to predators about their toxicity. Some poisonous caterpillars include the Monarch and the Pipevine Swallowtail. Some butterflies are poisonous. When a predator, like a bird, eats one of these butterflies it becomes sick, vomits violently, and quickly learns not to eat this type of butterfly. The sacrifice of one butterfly will save the lives of many of its kind. Many poisonous species have similar markings (warning patterns). When a predators learns this pattern (after becoming sick from eating one species), many species with similar patterns will be avoided in the future. Some poisonous butterflies include the Monarch (which eats the milkweed plant to become poisonous), the Small Postman butterfly, and the Pipevine swallowtail. Camouflage Some caterpillars blend into their surroundings extraordinarily well. Many are a shade of green that matches their host plant. Others look like inedible objects, for example bird droppings (the young Tiger Swallowtail larva). Most butterflies and moth protect themselves from predators by using camouflage. Some butterflies and moths blend into their environment so well that is it almost impossible to spot them when they are resting on a branch. Some butterflies look like dead leaves (like the Indian leaf butterfly), others look like the bark of a tree (e.g., the carpenter moth). Eyespots Some caterpillars have eyespots that make them look like a bigger, more dangerous animal, like a snake. An eye spot is a circular, eye-like marking found on the body of some caterpillars. These eyespots make the insect look like the face of a much larger animal and may scare away some predators. Some butterflies also have eyespots on their wings to deter potential predators. Hiding Some caterpillars encase themselves in a folded leaf or other hiding place. Mimicry Mimicry is when two unrelated species have similar markings. Batesian mimicry is when a non-poisonous species has markings similar to a poisonous species and gains protection from this similarity. Since many predators have become sick from eating the poisonous butterfly, they will avoid any similar looking animals in the future, and the mimic is protected. An example is the Viceroy which mimics the poisonous Monarch butterfly. Müllerian mimicry is when two poisonous species have similar markings; fewer insects need to be sacrificed in order to teach the predators not to eat these unpalatable animals. Tropical Queens and Monarch butterflies are two poisonous butterflies that have similar markings. Bad smells Some caterpillars can emit very bad smells to ward off predators. They have an orange, y-shaped gland on their neck which gives off a strong, unpleasant odor when the caterpillar is threatened. This keeps away dangerous wasps and flies that try to lay eggs in the caterpillar; these eggs would eventually kill the caterpillar as they hatch inside its body and eat its tissues. Many swallowtails have this gland, including the Zebra Swallowtail. Defense (cont.) (modified from: http://library.thinkquest.org/27968/coloring.shtml) One of the main reasons for butterflies’ popularity probably is their beautiful coloring. But this is more than only nice to look at. Dark colors help the butterflies to absorb the heat of the sunbeams they need because they can’t produce heat themselves. They are cold-blooded. Colors that often don’t seem so attractive to us can be useful to get invisible. Being forced to hide from patrolling birds and others many butterflies are real masters of camouflage. Bright colors and contrasts often are a warning to predators that the butterfly is poisonous. By imitating these colorings other butterflies profit from the deterrent effect (mimicry). Other butterflies look like "scaring" insects such as wasps or hornets. But not only this way predators are frightened and fooled. Big "eyes" appearing suddenly when the butterfly opens its wings scare attacking birds and others. Giving the impression of the head being on the backside is effective for protection, too. Predators normally attack what they consider the head so they catch the less sensitive part of this butterfly. They also expect it to escape in the other direction. However, not only between the different species of butterflies there are differences in coloring but also between male and female in some cases. And there are also particularities of coloring. (modified from: http://library.thinkquest.org/27968/camouflage.shtml) Among the different species of butterflies and moths, different ways of camouflage can be found. The simplest way is to copy the color of the background. Even structures of tree trunks are imitated perfectly. Other butterflies have dark and light stripes and patterns on their wings to get invisible in the lights and shadows in a bush, for example. Complex patterns make it difficult for predators to distinguish the outline of the butterfly from the environment. This is called "disruptive coloration". Other inedible things are often imitated, too. Some caterpillars and pupae look like bird droppings or twigs. The Indian Leaf butterfly (Kallima) is an example for the copy of a dead leaf. The upper side of its wings is blue and orange, but when it sits down on a twig it gets nearly totally invisible. It closes its wings showing a dull brown color with fine brown lines like the veins of a leaf and lies aside. The form and coloring of the wings make it hard to recognize the "living brown leaf". The camouflage coloration is always on the side of the wings that is visible when the animal rests. This means a butterfly’s is on the bottom side of its wings, a moth’s is on the upper side. The animals enforce the camouflage effect with their behavior: They normally sit down on backgrounds where the camouflage works best. Additionally, many of them pretend they are dead and don’t move. Some caterpillars even fall partially off their leaves. (modified from: http://library.thinkquest.org/27968/mimicry.shtml) Some butterflies defend against predators by incorporating toxins when they are caterpillars and eat plants containing these substances. The monarch butterfly is an example for this. It's caterpillars feed on milkweed plants which aren’t poisonous for the monarch but are for other animals. The monarch’s bright colors warn predators better not to eat this butterfly that will cause sickness. Having eaten such a butterfly once, a bird will always remember to keep away from it. Other species of butterflies which are not poisonous try to profit from the protective coloration, too. The viceroy butterfly mimics the monarch, for example. Over the years and generations the coloring developed by natural selection. Considering them poisonous, predators didn’t eat the ones looking like monarchs. The behavior of the "model" is also imitated and sometimes the mimicking butterflies fly with them in one group. Some species can mimic several different "models". The descendants of one female can have up to three different appearances. The males of another species must dispense with mimicry so that the females don’t mistake them for the copied species. The sphinx moth caterpillar even imitates a venomous snake when it feels menaced. The monarch butterfly and the milkweed bug have the same bright coloring and store the same toxin. This might be useful because the predators of the area must only remember one kind of coloration to keep away from. One experience saves the lives of two species. Monarch Migration (modified from: http://monarchwatch.org/) Fall Migration Unlike many other insects in temperate climates, Monarch butterflies cannot survive a long, cold winter. Instead, they spend the winter in roosting spots. Monarchs west of the Rocky Mountains travel to small groves of trees along the California coast. Pacific Grove, CA is well known for its winter monarch population. Those east of the Rocky Mountains fly farther south to the forests high in the mountains of Mexico. The monarch's migration is driven by seasonal changes. Day length and temperature changes influence the movement of the monarch. In all the world, no butterflies migrate like the monarchs of North America. They travel much farther than all other tropical butterflies, up to three thousand miles. They are the only butterflies to make such a long, two-way migration every year. Amazingly, they fly in masses to the same winter roosts, often to the exact same trees. Unlike birds and whales, individuals only make the round-trip once. It is their children's grandchildren that return south the following fall. Some other species of Lepidoptera travel long distances, but they generally only go in one direction following food. This one-way movement is properly called emigration. In tropical lands, butterflies do migrate back and forth as the seasons change. At the beginning of the dry season, the food plants shrivel and the butterflies leave to find a moister climate. When the rains arrive, the food plants grow back and the butterflies return. When the late summer and early fall monarchs emerge from their pupae, or chrysalis', they are biologically and behaviorally different from those emerging in the summer. The shorter days and cooler air of late summer trigger changes. In Minnesota this occurs around the end of August. Even though these butterflies look like summer adults, they won't mate or lay eggs until the following spring. Instead, their small bodies prepare for a strenuous flight. Otherwise solitary animals, they often cluster at night while moving ever southward. If they linger too long, they won't be able to make the journey; because they are cold-blooded, they are unable to fly in cold weather. Fat, stored in the abdomen, is a critical element of their survival for the winter. This fat not only fuels their flight of one to three thousand miles, but must last until the next spring when they begin the flight back north. As they migrate southwards, monarchs stop to nectar, and they actually gain weight during the trip. Some researchers think that monarchs conserve their "fuel" in flight by gliding on air currents as they travel south. This is an area of great interest for researchers; there are many unanswered questions about how these small organisms are able to travel so far. Another unsolved mystery is how monarchs find the overwintering sites each year. Somehow they know their way, even though the butterflies returning to Mexico or California each fall are the great-great-grandchildren of the butterflies that left the previous spring. No one knows exactly how their homing system works; it is another of the many unanswered questions in the butterfly world. Overwintering Sites Monarchs west of the Rocky Mountains return to the California coast, where they roost in eucalyptus trees, Monterey pines and Monterey cypresses. The clustering sites lie in bays sheltered from wind, or farther inland where they are protected from storms. Scientists estimate that the California monarchs make up about 5 percent of the overall worldwide Monarch population. Monarchs east of the Rockies migrate each year to the Transvolcanic mountains of central Mexico. Millions and millions of butterflies from the central and eastern Canadian provinces and the eastern and midwestern United States fly south to Mexico. Their flight pattern is shaped like a cone, as they come together and pass over the state of Texas on their way south. In massive butterfly clouds, they sweep up into the mountain ranges of central Mexico. In 1975 the scientific community finally tracked down the wintering sites of the Monarch in Mexico. Until then, the Monarch butterflies' winter hideouts had been a secret known only to local villagers and landowners. There is also a small group that lives in Florida that does not migrate. They overwinter in warmer areas of Florida. The sites the Monarchs use during the winter have particular characteristics that enable their survival. These characteristics are important because they provide the Monarch with the right overwintering conditions. Trees on which to cluster are one of the most important elements of the sites. The climate and the whole surrounding area are also important. Nearby trees, streams, underbrush, and fog or clouds all form an intricate natural ecosystem that is the monarchs' winter habitat. These conditions are found in oyamel fir forests, which occur in a very small area of mountain tops in central Mexico. Overwintering sites in Mexico are about 3000 m (almost 2 miles) above sea level, and are on steep, southwest-facing slopes. In particular, the butterflies need a cool place. When they are cool, they don't metabolize, or use up, their energy reserves as fast. They also need to be protected from snow and winds. The surrounding trees serve as a buffer to the winds and snow. Because they also need water for moisture, the fog and clouds in this mountainous region provide another important element for their survival. The butterflies choose spots that are close to but not quite freezing. They cluster together, covering whole tree trunks and branches, and cling to fir and pine needles. The forest floor in the overwintering sites is covered with young trees, shrubs, lichens and moss. When monarchs fall out of the trees and are too cold to fly back up, they can sometimes crawl to the lower bushes to avoid predators. The tall trees make a thick canopy over their heads. Protective trees and bushes soften the wind and shield the butterflies from the occasional snow, rain, or hail. Fog and clouds settle on the Monarch groves. On sunny days, they often warm up enough to fly to nearby water where they will drink. They must fly back to the roost before getting too cold, and one can sometimes see them take off in flight, heading back to the roosts as soon as a cloud passes over. Each of the above elements is important to the butterflies, and makes up the Monarch habitat - trees in which to roost, other trees and shrubs to protect them, the cool air, and the presence of water. Spring Migration As winter ends and the days grow longer, the monarchs become more active, beginning to mate and often moving to locations lower on the mountainsides. They leave their Mexican roosts during the second week of March, flying north and east looking for milkweed plants on which to lay their eggs. These monarchs have already survived a long southward flight in the fall and winter's cold; they have escaped predatory birds and other hazards along the way, and are the only Monarchs left that can produce a new generation. If they return too early, before the milkweed is up in the spring, they will not be able to lay their eggs and continue the cycle. The migrating females lay eggs on the milkweed plants they find as they fly, recolonizing the southern United States before they die. Soon the first spring caterpillars hatch and metamorphose into orange and black adults. It is these newly emerged monarchs, the offspring of the butterflies that made the fall journey, that recolonize their parents' original homes. Summer monarchs live a much briefer life than the overwintering generation; their adult lifespan is only three to five weeks compared with eight or nine months for the overwintering adults. Over the summer there are three or four generations of monarch butterflies, depending on the length of the growing season. Since each female lays hundreds of eggs, the total number of monarch butterflies increases throughout the summer. Before the summer ends, there are once again millions of monarchs all over the U.S. and southern Canada. Web References on Migration: http://www.tc.cc.tx.us/~dallard/monarch.html http://butterflywebsite.com/Articles/monarch.htm http://www.learner.org/jnorth/ http://www.sci.mus.mn.us/sln/monarchs/ http://ncnatural.com/NCNatural/wildlife/migrate.html#monarch http://www.education-world.com/a_curr/curr023.shtml Interesting Facts about Butterflies and Moths (modified from: http://library.thinkquest.org/27968/extremes.shtml) Extremes Size The world’s largest butterfly, Queen Alexandra’s Birdwing from New Guinea, can be up to 11 inches (27.9 cm) across, the world’s largest moth, the Atlas Moth sometimes measures one foot (30.5 cm) across. The Western Pygmy Blue only measures half an inch (1.3 cm) across, the Leaf Miner Moth even less: 1/8 inch (0.3 cm). Their caterpillars live inside leaves. Butterfly Migrations One of the biggest clouds of moving butterflies ever seen measured 250 miles (402 km) across. For a whole day, every minute over a million butterflies flew past. 26,000 butterflies passing by every minute have been seen in Ceylon. In a movement of the Painted Lady in California that took 3 days, the number of butterflies seen during daylight was estimated as 3 million. Death’s-head Hawk Moths have been found in Iceland. They are native to Africa and southern Europe. This means the animals flew nearly 500 miles (800km) over the sea without having a break. Variety / Diversity There are about 20,000 species of butterflies, the moths are even more numerous: about 150,000 species of them can be counted all over the world. Speed Some Hawk-Moths reach speeds up to 34 mph (54 km/h) when they fly. Some species of the Skippers family can do 37 mph (60 km/h). Development Time Some moths need up to 7 years to become an adult. Most of this time they spend as a pupa. There are Arctic moths that live 14 years as a caterpillar and are only active a few weeks each summer. The adult, however, only lives for one short season. The brimstone butterfly has the longest lifetime for adult butterflies: 9-10 months. Behavior (modified from: http://library.thinkquest.org/27968/amazing_behavior.shtml) Drunk Did you know that butterflies can get drunk? Some like the juice of rotten fruit which sometimes contains alcohol. When sipping this juice the animals can even get too drunk to fly. Fighting Some butterflies defend a site against other butterflies by fighting with them. They may even fight other insects or birds and be successful. Strange food Some moths only feed on the eye liquids of deer, cattle or elephants. The Asian vampire moth can pierce an animal’s skin and drink its blood. Symbiosis Hairstreak and Metalmark butterfly caterpillars produce a nutrient-rich droplet for ants, like aphids do. The ants in return, defend the caterpillars against predators like spiders, predatory bugs and parasitic wasps and flies. The caterpillars can communicate with the ants by using sound vibrations that travel along a leaf surface. Marking As they move to new feeding grounds, tent caterpillars always mark their way to return with a thread of silk. Houses The caterpillars of Bagworm Moths build a case around themselves which they always carry with them. It is made of silk and pieces of plants or soil. The case is opened in the front for the head part of the caterpillar with the legs and in the back to let out fecal pellets. The caterpillar even pupates in this case. The females never leave it and as adults they stay in the case and emit fragrances to attract males. When a male has found a female, it puts its abdomen into the case to mate. Afterwards the female lays her eggs in the case and falls out, dead. The hatching caterpillars will leave the case immediately to built one themselves. Underwater life The caterpillars of some Snout Moths live in or on water-plants. They have evolved two ways to breathe. Some spin parts of plants together in order to get a hollow space filled with air. Others have gills. One species spins a net to catch pieces of food and air-bubbles. The adult butterfly of one of these species hatches underwater and is covered by a wax protective layer. The wax also gives buoyancy to the butterfly and is lost as the animal moves to the surface. When it has reached the surface, the butterfly moves to the shore and straightens its wings. Caterpillar Movement Processionary caterpillars always walk in a single file to their feeding sites. If the first one goes in a direction that leads it to th back of the last one, the caterpillars can walk in circles for hours. Avoiding Danger Some caterpillars can eat animals that are stuck to surfaces of carnivorous plants. The caterpillar has detachable scales that it uses to pave its way over the sticky surface of the plant. It won’t stick to the surface but can eat other animals stuck to the plant. Licking Stones You can sometimes see male Red Admiral Butterflies lick stones. They put a bit of spittle on the stone to dissolve minerals from it and then they lick it up. Lesson 1: Introduction to Lepidopterans by Observing Butterfly and Moth Diversity Objective: Use observation skills to characterize the morphology and diversity of butterflies and moths. Time: 2 - 30 minute sessions Materials: Posters of butterflies and moths Butterfly coloring sheet Crayons Individual pictures of butterflies, moths, caterpillars Museum Butterflies and Moths Procedure: Ask the students if they have ever seen a caterpillar, or a butterfly. What did they look like? You should get a variety of responses for this question. Talk about how not all butterflies are the same. This will introduce the concept of animal diversity. Talk about moths. How are they different from butterflies? The instructor will need to point out differences, although the students will probably be able to tell you that they come out at night. Place posters of butterflies on the floor and have the children gather around them. Ask the students to point out differences (size, color, shape, etc.) and similarities (eg. Monarch vs. Viceroy). Take a walk around a flower garden and see how many butterflies the students can find. Talk about the different colors, sizes, and food sources. Are all of the butterflies on the same species of flower? Or do they seem to prefer certain flowers? Activity: Using butterfly coloring sheet - Have the students color the different pictures and make some into butterflies and some moths (they will need to draw antennae for this). Collect these and display them so that the students can observe the variety (diversity) within their class. Enrichment: In a center put out pictures of butterflies and moths and have the students categorize them (butterfly, moth, large, small, by colors). In a center put out pictures of caterpillars and their respective butterflies or moths and have the students match them (use a key on the back of the pictures so that students can see if they are correct). Lesson 2: Butterfly and Moth Life-Cycle Introduction Objective: To introduce the students to life-cycles, especially Lepidoptera. Time: Variable Materials: The Very Hungry Caterpillar (Eric Carle) Butterfly life-cycle puzzle worksheet Copies of butterfly book pages for each student Crayons Butterfly life-cycles theme unit Procedure: Read the story "The Very Hungry Caterpillar" (Eric Carle) to the students. After you have read the story discuss what happened to the caterpillar during the story. Did it grow? What did it eat? Where did it live? What happened at the end? Did the butterfly look anything like the caterpillar? Let the children examine the illustrations to answer some of these questions. You may also use the floor puzzle that goes with the book to illicit some responses. Talk about how all animals (including humans) grow and change throughout their lives. Do activities from the Life-cycle Theme Unit. Activities: Butterfly Life-Cycle Puzzle: Have the students color the butterfly and the four life-cycle drawings. Cut out the four circles and glue them to the butterfly in the correct order (1=butterfly laying egg on leaf; 2=caterpillar hatching from egg; 3=crysalis hanging from plant; 4=butterfly). Butterfly Book (8 pages): Have the students color and cut out the butterflies for this book. Discuss the stages of the metamorphosis and have the students answer the questions on the pages. At the end, they will have a butterfly-shaped book that goes through all of the stages in a butterfly life-cycle. This can be done over several periods, and attached at the end. Other Resources: Butterfly Life-cycle Poster The Magic School Bus Butterflies Video From Caterpillar to Butterfly (Book) The Butterfly Metamorphoses Book Butterfly Metamorphosis Models (plastic and foam) Lesson 3: Growing Butterflies to Observe Their Life-Cycle Objective: To teach the life-cycle of Lepidopterans by observing the actual metamorphosis from egg to butterfly. Time: Variable - ~30 minutes/day for 3-6 weeks depending on species Materials: Butterfly Nursery Butterfly eggs Copies of egg, caterpillar, chrysalis and butterfly cut-outs Butcher paper for pictographs Journals Procedure: Prior to starting this unit, order live butterfly eggs. Assign students to groups (1-2 eggs / 3-4 students). You will inevitably get some mortality, so be prepared with "extras". Have the children describe the eggs, leaves, etc. Have them "name" their egg. Follow directions that come with "The Butterfly Nursery" for care of the eggs, caterpillars and butterflies. Have each group of students keep a journal (1-2 sentences/day) describing what they observe about their "egg…." each day. Have them note how long before their egg hatches, how many times the caterpillar molts, how long before the caterpillar turns into a chrysalis, and how long the chrysalis stays before the butterfly emerges (days). Use pictographs to track each of these stages. There will be some variation within the class. Some suggestions for graphs include: class graphs of length of egg stage, length of caterpillar stage, number of molts, length of chrysalis stage, and within-group graphs of all stages to compare stage lengths within the group. Use egg, caterpillar, chrysalis and butterfly cut-outs for pictographs. Release the butterflies near a flower garden and have the children hypothesize what will happen to them. Make sure to take pictures along the way to enhance the journals. Enrichment Activity: A class activity could include putting a Powerpoint (computer presentation program) presentation together, depicting their class project on raising butterflies, to be presented to parents in a unit culminating celebration. A group of 2-3 students could be assigned one stage of the project to depict on one slide. The students would discuss, with the teacher's guidance, what were the important and fun parts of this stage and what would show that best on the slide. Pictures, graphs, simple sentences could all be used. An alternative would be to have the students put their journal, with pictures, into a web site and publish on the web. Lesson 4: Butterfly Coloration Objective: To introduce the students to the concepts of mimicry, camouflage, and warning coloration. Time: 60 minutes - can be split into several shorter sessions Materials: Flash cards of mimicry, camouflage and warning in butterflies and moths Large butterfly coloring sheet for each student Crayons Procedure: Talk to the students about differences in colors of butterflies. Are all butterflies brightly colored? Are some dull colored and blend into their habitat? Are some similar in color or markings to others? See if the students can come up with any examples. Use flash cards of different butterflies and moths to give examples of mimicry (Monarch vs. Viceroy), camouflage (moths) and warning (Monarch) coloration. Talk about the advantages of each of these adaptations. Give the students the coloring sheet and have them each color one butterfly that has warning coloration (bright colors or eyes) and one that is camouflaged (blends in to something in the classroom). For example, a student might color the warning one florescent yellow and pink with 2 big owl eyes and the camouflaged one the same blue and red pattern of the carpet in the room. Cut out the butterflies. Divide the class into 2 groups. Send Group One out of the room (bathroom break or recess……) and have Group Two tape their butterflies around the room (put the camouflaged ones where they match and the warning ones where they stick out). Bring Group One back into the room and explain to them that they are birds. Some birds like to eat butterflies. Give them 5 minutes to go around the room and "eat/gather" as many butterflies as they can find. Remind them that the warning coloration should tell them that that butterfly is "yucky" and they should not eat it. After time is up, have all of the students sit down and see which butterflies were "eaten". Have the Group Two go point out any that were not eaten. Discuss why each butterfly was not eaten and which ones were best camouflaged. Switch roles and repeat activity. Group One will hide their butterflies and Group Two will be "birds". Wrap up this lesson by a walk outside, looking for different color butterflies and moths to see if the children can pick out distinct coloration. Enrichment: In a center, have pictures of butterflies and moths and a corresponding picture of what they are mimicking or using as camouflage. Have the students match the butterfly/moth with the corresponding picture (have a key on the back of matching pictures). Lesson 5: Monarch Migrations Objective: Teach students about movements of animal populations in order to find resources and habitats to allow their survival. Time: 30-60 minutes - can be split into several shorter lessons Materials: Monarch Butterfly of Aster Way book and tape Map of North America (including Mexico) Procedure: In a center, have the children read and listen to the book "Monarch Butterfly of Aster Way". Use this as an introduction to migrations. The book follows a Monarch from a flower garden in the United States to its wintering site in Mexico. Talk to the students about migrations that they might know about, such as water fowl (ducks, geese). Have them suggest for reasons that animals might need to move from one site to another. Lead them towards things like temperature, snow cover, and food sources. Many animals migrate south during the winter to avoid cold weather. Cold weather brings snow that can cover or kill many plants that the animals need for food. Insects are "cold-blooded" and therefore are unable to regulate their temperature. If the air temperature falls below freezing, their body fluids will freeze and kill them. Many insects, including many butterflies and moths, go through a dormant stage that allows them to overwinter in cold climates. Monarchs typically migrate to a warm climate. Most of the Monarch butterflies from east of the Rockies fly all of the way to a site in Mexico, near Mexico City, where the temperature is warmer. So populations, such as those west of the Rockies, fly to the coast of California, near Monterey Bay (Pacific Grove is famous for their Monarchs). Florida Monarchs stay in southern Florida. Monarch caterpillars eat only milkweed leaves and therefore need a steady supply of this plant to survive. Stress the fact that the same butterflies that leave in the fall return in the spring, but that there are several generations during their time in the US. This means that some butterflies never make the migration and those that do, only make it one time. Use the map to demonstrate the migratory routes of Monarchs. Enrichment Activity: There are many web sites that deal with Monarch Migrations. If this unit is started early in the spring, then some of these sites can be used to track the migration of Monarchs from their first arrival in the US in March and their spread throughout the US to southern Canada in June and July. Some of these sites are: http://www.tc.cc.tx.us/~dallard/monarch.html http://butterflywebsite.com/Articles/monarch.htm http://www.learner.org/jnorth/ http://www.sci.mus.mn.us/sln/monarchs/ http://ncnatural.com/NCNatural/wildlife/migrate.html#monarch http://www.education-world.com/a_curr/curr023.shtml Lesson 6: Butterfly and Moth Wrap-up: Objective: Summarize the lessons on Butterflies and Moths, highlighting diversity, lifecycle, coloration, and migration. Time: Variable Materials: All models, posters, puzzles, books, pictures, etc. Recipes (caterpillar and butterfly snacks, eat like a butterfly) Cups, plates, etc. Procedure: Have a class discussion of what the students have learned about butterflies over the course of the unit. Ask leading questions, for example "Who can tell me one thing that separate butterflies and moths?" or "What butterfly migrates to Mexico every year?"…. Ask the students to each tell one thing that they really liked about butterflies and moths. Use the day as a special butterfly day. Have all of the materials available for the students to use in centers or around the room. Make caterpillar and butterfly snacks. Drink like butterflies. Give a presentation to the parents at snack time on what the students have learned about butterflies. (Powerpoint Life-Cycle here?) Play the Follow the Butterfly Game, to summarize the interaction between lifecycles and migrations.