Ma. Corazon C. Rodolfo

advertisement

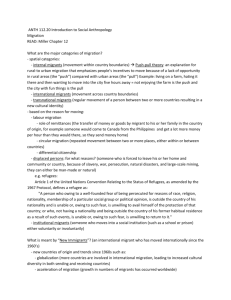

LIFE AFTER MIGRATION: RETURNED INDONESIAN WOMEN MIGRANT WORKERS IN CENTRAL AND EAST JAVA Ma. Corazon C. Rodolfo Consultant/Independent Researcher Free-lance Translator/Interpreter, Asian Development Bank Abstract It is at the family and local community where the benefits of Indonesian international labor migration have been most dramatically felt. Over the past three decades, Indonesian women have been migrating autonomously as main economic providers. The impact of Indonesian female labor migration on families and communities of origin is not limited to benefits gained from their remittances. Migration is a pro-active agent of socio-cultural change. It reshapes gender, family roles and relations. Their eventual return requires reworking traditional relationships with their families and communities. Returned migrants bring in new ideas, attitudes and behavior brought about by their exposure to other ways of life. This paper presents findings gathered from field observations, in-depth interviews and Focus Group Discussions in communities in Central and East Java provinces-- two of the leading areas of origin of migrant workers. Changes concerning the returnees, their families and communities were observed. In retrospect, the returnees’ level of preparedness prior to departure, their living and working conditions, challenges met, and support networks in countries of employment are presented to gain a better understanding of these changes. Initial recommendations pertinent to Law No. 39 that seeks to regulate Indonesian labor migration and protect migrant workers are presented. Introduction It was during my transit in Singapore in November 2004 when I chanced upon a group of Indonesian women overseas workers returning to their country of birth. I could sense their excitement and anxiety in returning to their Tanah Air (Fatherland). As a public servant who has worked on various programs for Filipinos overseas for more than a decade, I could not help but feel a sense of déjà vu.1 This scene at the airport opened my eyes to another reality as I realized how little I knew about Asian migrants other than my own compatriots. Considering that Asian migrants are estimated to account for one fourth of the global migrant stock, this poignant scene is witnessed daily in other international airports all over Asia. China with a diaspora of 30 to 40 million, India with 20 million, and the Philippines with 8 million--are the top three countries of origin of migrants and recipients of foreign remittances.2 In 2005, the 1 The author worked for 12 years for the Commission on Filipinos Overseas, an agency attached to the Philippine Department of Foreign Affairs prior to its transfer to the Office of the President in August 2004. She served as Director of the Planning, Research and Policy Office of said agency from January 2000 to September 2006. She was part of the core group of the Overseas Absentee Voting Secretariat of the Foreign Affairs Office which was responsible for the initial implementation of the Overseas Absentee Voting Act of 2003. This law finally enabled Filipinos overseas to vote in the national elections in May 2004, or 17 years after it was enshrined in the Philippine Constitution of 1987. 2Data from the International Migration on Migration accessed at http://www.iom.int/jahia/Jahia/cache/offonce/pid/254 on 27 July 2006. 2 United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UN ESCAP) reported that a total of US$167 billion was remitted by labor migrants through formal banking channels alone. Remittances to China which amounted to US$21.7 billion, India with US$21.3 billion, and the Philippines with US$12.5 billion, accounted for 30% of the total amount sent worldwide. Combined with remittances to Bangladesh, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Thailand and to a lesser extent, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Nepal, and the Pacific Island of Samoa, foreign exchange sent to the region accounted for more than 40% of global remittances. Existing literature describe Asian international migration as having changed substantially over the past three decades in terms of magnitude, direction, and character. As noted by Prof. Hugo, international migration has a significant influence on the economic, social and demographic development in the region and is constantly in the public consciousness”.3 International labor migration is not a new phenomenon in the Asia Pacific region.4 It entered a new era in terms of magnitude and complexity with the increase in oil prices in 1973 in the Middle East which made possible the development of large-scale infrastructure projects in these countries and required a very large number of male workers initially from Egypt and neighboring Arab countries. Due to the very large demand for manpower, the Philippines, India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Thailand, South Korea, and Indonesia became major sources of overseas labor. Falling oil prices and completion of construction and infrastructure projects in the mid-1980s signaled the decline of the massive entry of foreign male construction workers in the Middle East. There was increased demand for foreign female domestic workers, however. Developments were also shaping up in Asia as Taiwan, South Korea, Hongkong, Singapore, Thailand and Malaysia achieved very significant economic growth and by the 1980s, these “Asian Tigers” became capital intensive and joined the ranks of wealthy and industrialized nations. Their vast labor requirements necessitated the entry of foreign guest workers to do dirty, difficult and dangerous (3D) jobs that their nationals shun. 3 Graeme Hugo, 2005, Migration in the Asia Pacific Region, a paper prepared for the Policy Analysis and Research Programme of the Global Commission on International Migration, Geneva: Global Commission on International Migration, page 2. Accessed at http://www.gcim.org/inm/File/Regional%20Study%202.pdf. 4 Graeme Hugo and Anchalee Singhanetra-Renard, 1988, International Labor Migration in Indonesia: A Review, Mimeo. 2 3 Indonesia’s entry as a major source of labor migrants came later compared to the Philippines, India and Thailand but “gained momentum over the last two decades and has become one of the main Asian countries of origin of labor migrants especially with the onset of a prolonged economic crisis in 1997”.5 The Indonesian Government has integrated overseas employment in its development plans and set targets for the deployment of migrant workers. 6 Over the years, Indonesia has sent the largest number of foreign migrant workers in the ASEAN region, particularly to Malaysia where ‘Indonesians comprise the bulk of the foreign worker population, accounting for about 73%’7. It is estimated that there are between 2.5 million to 5 million Indonesians overseas mostly in Malaysia, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and Singapore.8 Other destination areas are Taiwan, Hongkong SAR, United Arab Emirates, Brunei Darussalam, South Korea, Kuwait, Japan, Bahrain and Qatar. Next to West Java, East and Central Java are leading provinces of origin of migrant workers.9 About 88.6% of female migrants come from Java Island. In areas outside Java, male migrants outnumber females. Indonesian women migrant workers started to be officially deployed overseas under the New Order Government’s Second 5-Year Development Plan (1974-1979). Over the years starting in 1989, women began to dominate the migrant worker sector. From 2000 to 2005, female migrants accounted for 85% of the total number of labor migrants recorded by the Indonesian labor office.10 Major destination countries are the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Malaysia, Singapore, Kuwait, United Arab Emirates, Hong Kong, Brunei and Taiwan. The Asian economic crisis of 1997 and its devastating impact on workers, growing demand for women workers especially in the domestic service sector, the Indonesian Government’s active promotion of markets for its workers and acceptance of lower salaries, lesser benefits and ‘obedience’ to foreign employers 5 Graeme Hugo, 1998, Undocumented International Migration of Women in Southeast Asia: Major Patterns and Policy Issues, in International Migration in Southeast Asia: Trends, Consequences, Issues and Policy Measures, C.M. Firdausy, ed., Under the South East Asia Research Program, The Toyota Foundation, Jakarta: Ciptamentari Saktiabadi. 6 Graeme Hugo, 2004, International Migration in Southeast Asia since World War II in International Migration in Southeast Asia, A. Ananta and E. N. Arifin, eds., Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, page 59. 7 Cited in ADB, 2006, p. 6. 8 Accessed at Indonesian Ministry of Manpower and Transmigration website at www.tki.or.id. 9Based on existing literature on Indonesian international labor migration and discussions with officers at the Ministry of Manpower and Transmigration in Jakarta in June to July 2006. 10Based on data accessed at http://www.nakertrans.go.id. in July 2006. 3 4 have led to increasing feminization of Indonesian labor migration, albeit under less favorable terms and conditions compared to their Filipino and Thai counterparts.11 Research Objectives, Rationale and Methodology According to Ghosh (2000), the impact of return migration in Asia has traditionally been neglected in the migration literature with very few information on return migrants.12 More specifically, Sukamdi et al (2001) observed that in Indonesia, “no sufficient attention has been given to Indonesian returned migrant workers, particularly on the problems of remittance and readaptation to the area of origin”, thus, there is “room for studies illustrating the existence and importance of return migration given that similar studies have been done in Asia.”13 In Indonesia, the economic and social impact of migration at the national level is still limited.14 It is at the family and local community where the benefits and costs of overseas employment are most felt. A number of studies on returned female overseas workers, their families and communities have been conducted. These studies have revealed the following: greater involvement of returnees in family decision making, particularly on financial affairs15, positive feedback on overseas migration in the community due to relatively high economic returns, investments in human capital16 and absence of problems reported, entrepreneurial and small scale trading activities, as well as confidence and sense of independence among returnees.17 Adi R. (1996) noted the intensity in terms of changes in gender power relations is still very low 11See ADB, 2006, p. 72. Also Nagib, et al., 2001, Studi Kebijakan Pengembangan Pengiriman Tenaga Kerja Wanita ke Luar Negeri (Policy Study on the Development of Deployment of Women Overseas). Jakarta: Office of the State Minister for the Empowerment of Women in cooperation with the National Research Center on Population and Labor, Indonesian Institute of Sciences, p. 2. 12 Bimal Ghosh, 2000, Return Migration: Reshaping Policy Approaches in Return Migration, Journey of Hope or Despair?, B. Ghosh, ed. ,Geneva: International Organization for Migration. 13 Sukamdi, Setiadi, A. Indiyanto, A. Haris and I. Abdullah, 2001, Country Study 2: Indonesia in Female Labour Migration in Southeast Asia: Change and Continuity, S. Chantavanich, et al eds., Bangkok: Asia Research Center for Migration, Institute of Asian Studies, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, p. 128. 14Contribution of official remittances to Indonesia’s Gross Domestic Product is less than 1%. 15Yayasan Pengembangan Pedesaan (Rural Development Society), 1992, Trade in Domestic Helpers, Indonesia (With a micro study from East Javanese Domestic Helpers), Final Report. Rural Development Society. 16See Sanggar Kanto, 1998, Migrasi Internasional Tenaga Kerja Wanita dan Pengaruhnya Terhadap Kondisi Sosial Ekonomi Rumah Tangga dan Masyarakat di Pedesaan: Studi Kualitatif Migran TKW di Desa Pagak, Kabupaten Malang, Jawa Timur (Female International Labor Migration and its Effects on the Socio-Economic Conditions of Rural Households and Communities: A Qualitative Study on Female Migrants in Pagak village, Malang Regency, East Java), Universitas Brawijaya, Malang. 17 See Sri Rum Giyarsih and Umi Listyaningsih, 2002, Dampak Non-Ekonomi Migrasi Tenaga Kerja Wanita ke Luar Negeri di Daerah Asal (Non-Economic Impact of Female Labor Migration Overseas on the Community of Origin), Research Report. Women’s Studies Center, Research Institute, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta. 4 5 notwithstanding the significant improvement of the returnees’ economic status as a result of their employment in the Middle East.18 A more recent study (2003)19 revealed challenges to some existing myths foremost of which is that women are ‘mere followers of men’ and ‘operate only in the kitchen, water well and bed’ as the returnees’ bigger economic role has improved their bargaining position and modified gender relations. With more Indonesian women migrating autonomously as main economic providers and fewer of them migrating as dependents of their husbands or other men in their families, the impact that returnees have on their communities of origin as agents of socio-cultural change deserves closer attention. Migration reshapes gender, family roles and relations. Female migrants’ eventual return to their families and communities requires reworking traditional relationships. Furthermore, migration has exposed them to affluence and other ways of life, new ideas, attitudes and behavior. My revisit to Indonesia in November 2005 until August 2006 made possible under the auspices of the Asian Scholarship Foundation enabled me to go beyond my initial impressions of returning Indonesian migrant workers. My field work in selected villages in the Regencies of Banyumas and Blitar in Central and East Java Provinces, respectively, provided me the opportunity to seek answers to questions I wanted to ask returned women migrant workers on how life has been for them, their families and communities upon their return. What is their present role in their families and communities? How has their absence and eventual return affected these two basic social units? What new things and ideas have been introduced by the returnees? In retrospect, what were their motivations for working overseas? How prepared were they to work abroad? What were their living and working conditions and support networks in their countries of employment? How did they cope with challenges? Research sites (villages, or desa) were selected based on consultations with local officials. Indepth interviews of 56 returnees in selected villages were conducted. These were validated by 18 R. Adi, 1996, The Impact of International Labour Migration in Indonesia, Ph.D. dissertation, University of Adelaide. Also in Hugo, 1995a, p. 295. 19See Muzakka, M. Suyanto and C. Kepirianto, 2003, Mobilitas Internasional Tenaga Kerja Wanita: Studi Perubahan Sosial Ekonomi Rumah Tangga Tani Desa Banjarsari Kecamatan Nusawungu Kabupaten Cilacap (Female International Labor Mobility: A Study of Socio-Economic Change in Agricultural Households in Banjarsari Village, Nusawungu District, Cilacap Regency), A Report. Universitas Diponegoro, Semarang. 5 6 observations and immersion in these villages. Separate Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) were conducted for several groups of key informants such as children and spouses of returnees, nonmigrants, and formal and informal community leaders. Formal community leaders included the village heads and members of the village legislative council. Informal community leaders included former political leaders, educators, religious leaders and other influential personalities in the community (known as tokoh masyarakat) whose advice is sought and respected in village meetings and in day-to-day affairs by many villagers. Findings A Brief Profile of the Respondents Majority of the returnees interviewed in East Java were between 30 to 39 years old, while those from Central Java were younger with almost half of them aged 25 to 29. Most respondents from both provinces finished primary education, followed by those who completed junior high school. The very few who completed senior high school were employed as factory workers. Only 10% of the respondents were single at the time of the interviews. More than half of married respondents in both Central and East Java have only one child, followed by those who have two children. The average age of their children was 10 years and below. Slightly less than half of the respondents in East Java have been home for less than one year, and the rest have returned from less than two to six years. Respondents from Central Java have been home from less than one to 13 years and most of them left again to work overseas for the following reasons: to save capital for business, defray the family’s daily expenses and children’s education, build or complete the construction of their house, and purchase household appliances. There were fewer return migrants in East Java and they were compelled by the same economic reasons. Non-economic motivations included kind employers, desire for personal advancement, and escape from personal problems. Most of the returnees have family members or relatives who used to or are still working overseas. The Returnees: Life after migration Most of the returnees are full-time housewives. An equal number divide their time managing their households and tending the small business they established upon return. Overseas labor migration, however, has not served as a catalyst for them to seek work outside their home. A 6 7 number of the relatively ‘successful’ returnees in Central Java, though, have assumed an active role in their communities. Sutina (not her real name) is a case in point. She divides her time taking care of her six-year old daughter and being actively involved in village civic activities on health and education. She also organized a play group for children of school age who would otherwise not be able to join one due to their village’s distance to the nearest pre-school and the lack of transport. The play group regularly meets in her house and she provides all the materials needed. Her husband drives a public transport van which they bought from her earnings overseas. Their van has provided the only means of transport in their village other than the “ojek” (motorcycle for hire).20 While agriculture continues to be the main source of income of most of the respondents in East Java, an increase in entrepreneurial activities especially among returned women migrant workers was noted. Land ownership was made possible by earnings abroad. Respondents in Central Java were mostly engaged in small business. For those engaged in agriculture, land ownership was also made possible by their earnings abroad. More than half of the respondents in East Java live on less than US$30 a month or US$1 day. For Central Java, monthly earnings were slightly higher at US$30 to US$49 or a little less than US$1 a day. Earnings from overseas employment also made home ownership possible. Most of the newly built or renovated houses which differ from the traditional Javanese house are perceived as symbols of the owners’ improved economic conditions. In Javanese society, the house stands for many things. It is a payung hidup21 (umbrella of life) that provides protection and comfort to its inhabitants and bestows self-identity and prestige to the family. These conspicuous symbols of ‘success’ reinforce the belief in the community that women are more reliable sources of income than their male counterparts.22 Their success could be attributed to other facts attendant to the recruitment process. Unlike the men, women do not need to pay cash when they sign up with recruitment agencies as recruitment and other related fees are deducted from their salaries when they are already deployed overseas.23 In 20 In-depth interview in Wiradadi village in Banyumas Regency, Central Java, 24 April 2006. Focus Group Discussions in Ngeni village in Blitar Regency, East Java, 18 February 2006. 22FGDs with formal community leaders in Ngeni village, Blitar Regency, East Java on 16 February 2006. 23This was expounded during FGDs with formal and informal community leaders in Wiradadi village, Banyumas Regency, Central Java on 30 April 2006. 21 7 8 the long-term, this arrangement is more onerous as it entails bigger salary deductions and longer repayment periods. Increased confidence, assertiveness and self-reliance were noted among the returnees. As the husband of a returnee from East Java observed, “even though my wife worked as a domestic helper overseas, she became more self assured upon her return and she no longer works on the land but prefers to tend her store”.24 Not a few returnees admitted that they were “happy to be back but at the same time, feel disoriented, and oftentimes tend to compare their living and working conditions abroad with those in the village. They often wish to work abroad again”. Increased consumption among returnees was noted but only for as long as their resources allowed.25 There were generally high expectations on international labor migration prior to migration. Upon return, there was awareness on their rights as migrants and the realization that “overseas employment is not easy and is often fraught with risks and therefore requires a lot of preparations”. Some respondents returned with negative views in view of the problems they experienced but were ambivalent when asked if they would work overseas again. Not all women returned successful.26 A feeling of anxiety and sadness pervades among those who see themselves as “failures.” Over time, they have found comfort by attributing everything to ‘destiny’ (nasib). Marital and unresolved personal problems were other sources of anxiety for the returnees. Glimpses of another culture Their experience in other countries has made them realize that there is not one, but many cultures. These ways of life can be ‘liberating’ given their exercise of freedoms and rights in countries such as Taiwan, Hongkong, South Korea, or ‘restrictive’ given limitations in female mobility and other social taboos in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Learning another language was identified as a major cultural learning. Foreign language borrowings from Malaysian, English and Arabic words and adoption of new accents were noted among newly arrived returnees or 24FGDs with husbands of returnees in Ngeni village, Blitar Regency, East Java, 19 February 2006. This was stated by the returnee during my in-depth interview on 3 February 2006. 25 Usually 3 to 6 months after return. FGDs with non-migrant families in both Blitar and Banyumas Regencies on 19 February 2006 and 29 April 2006, respectively. 26 Interview with family and closest neighbor, another returnee in Ngeni village, Blitar Regency, East Java on 5 February 2006. 8 9 those who have stayed abroad for a relatively long period of time. Returnees learned to adapt to foreign cuisines not deemed haram (forbidden) in Islam. Said exposure to foreign cuisine did not, however, result in a “shawarma-like phenomenon” in their families and communities.27Respondents noted the difficulty in observing their religious practices in a nonMuslim country as they were often forbidden to fast and pray five times a day. Notable practical learnings such as the inculcation of a work ethic, time management, discipline, and efficiency, awareness on health care (sanitation, better nutrition) and child rearing were deemed useful. A few did not find their skills gained useful due to lack of work opportunities in the village. The respondents were unanimous in wanting “higher education, even up to university level, or at least, senior high school education”…“work outside the village or away from the farm”… and “comfortable and better jobs” for their children. They do not want their children to experience what they have been through, and if their children would later on decide to work abroad, this should be under different and better circumstances. Agriculture was not an attractive option given its low productivity levels and constraints on agricultural development in the village. The returnees’ families In-depth interviews show autonomous decision-making notwithstanding that parental or spousal approval is part of the official administrative procedure.28 Traditionally, female labor is not an issue in Javanese society, particularly among lower class women. The findings in the villages studied indicate continuity in the context of lower class women working to help generate household income, but some changes in the nature of the income, its sources and uses were noted. Prior to the advent of international migration, family income in Javanese rural communities was delineated into “duwit lanang” and “duwit wedok”. Duwit lanang referred to the husband’s income which is bigger and used for the family’s major needs such as land, house and education, among others. On the other hand, duwit wedok referred to a woman’s supplemental income used for daily needs such as food, donations, savings and children’s 27The “shawarma” is a Middle Eastern sandwich introduced by returning Filipino workers from the Arab Gulf states. Its popularity reached its peak in the mid-1990s. This was observed in Aguilar, Filomeno, ed., Filipinos as Transnational Migrants, Philippine Sociological Review, vol. 44, nos. 1-4, January-December 1996, p. 111. 28 A letter of approval from parent/spouse is required for men and women who wish to work overseas. Some recruitment agencies/agents reportedly requisite documents in villages where local officials are lax. 9 10 allowance.29 This delineation no longer holds true as women’s earnings from abroad turned out to be more than just supplementing the family income. Female labor migration has more than just improved their families’ economic conditions. The returnees’ bargaining position with their families has been enhanced. The term “musyawarah” (consultation during decision making) has been more frequently resorted to. The support of the extended family was important in managing the household in the women’s absence. The men who were left behind assumed household chores which in traditional Javanese society were considered ‘women’s work’. While adjustments in the pattern of household work made during the women’s absence have led to some changes upon return, the couple’s public role has not drastically been altered. Communities of Origin In the mid-1960s, southern Blitar (unlike the north which is more fertile and has irrigation) was described as a “subsistent (‘daerah minus’) and isolated area”. In his speech during the offering ceremonies to the Goddess of the Southern Seas (known as Larung Sesaji Pantai Tambakrejo) in Tambakrejo Beach, Wonotirto Sub-district on 01 February 200630, the newly installed Regent of Blitar, H. Herry Noegroho cited the significant role that remittances from labor migrants have played in improving the lives of the people in the south. He noted that the foreign exchange sent by overseas workers to the Regency since the early 1980s have made southern Blitar almost at par with the north. Banyumas Regency is another major area of origin in Central Java Province. As observed by H. Suyatno, head of the Regency’s local Manpower and Transmigration Office, the ‘trickle down’ effects of remittances have benefited not only migrant households but other sectors especially trade, construction and transport.31 Overseas remittances have changed the landscape of the villages. Ownership of motorcycles and even private vehicles and trucks has increased significantly.32 In both communities, the “success” of most of the returnees has been conspicuous--many of them bringing millions and billions of 29 Referred to Irwan Abdullah, 1997, Sangkan Paran Gender (The Role of Gender), Yogyakarta: Pusat Pelajar, pp. 208-209. Also in Suyanto et al, 2001, p. 45. 30 During the ceremony, the Regent conferred to the author the symbolic kris (sword) to Blitar as a sign of welcome. 31 Ibid. 32Based on interview with Mr. Bambang Hermanto and Ms. Andini, principal and guidance counselor, respectively, of the lone junior public high school in Wonotirto, Blitar Regency. Such was not the case 5 to 7 years ago. 10 11 rupiahs to the community to build or renovate their homes, send their children to school, buy land, motorcycles, household items and establish stores/small business. Contributions to the local economy, particularly in providing means of transport33 and introducing ‘new’ technology, were cited by community members.34 Returnees have also facilitated family members’, relatives’ and neighbors’ migration by providing or lending money to pay the recruitment fees. Communities have become more open to overseas employment, even domestic work, in view of relatively higher pay.35 Improvement in economic status did not alienate community members from the returnees for as long as these changes did not threaten community traditions, customs and values and the returnees know their place (“tahui diri”).“Iyah (not her real name) learned to celebrate her birthdays in Malaysia, but is cautious of her neighbors’ reaction if she were to do the same in her village. While milestones such as births, circumcision, weddings and funerals are celebrated in Javanese rural communities, birthdays are still seldom celebrated.”36 On the other hand, Istin (not her real name), a returnee also from the same village openly celebrates her family members’ birthdays since she returned. This practice and her liberal manner of dressing are frowned upon by her neighbors.37 Customary laws regulate the day to day activities in these communities. Cultural practices surrounding births, circumcisions, weddings, funerals and other rites of passage are observed. Returnees use technology (such as video recording) and ‘lavish’ amenities by village standards (better “kebayas”/traditional Javanese dresses, more food during feasts) in observing these customs. Formal and informal leaders and the community in general are effective enforcers of social order.38 Returnees who are perceived as being inebriated by money (“mabuk duit”), disrespect their husbands and no longer know their place are frowned upon.39 33 See case of Sutina earlier discussed. In-depth interview with Riyah (not her real name) in Ngeni village in Blitar Regency, East Java, 29 January 2006. She established a photocopying/laminating cum school supplies store—the only one in the village. 35 In Jakarta, informal workers earn between US$20 to US$50 compared to US$129 in the KSA and US$450 in Hongkong SAR. 36 In-depth interview with Riyah in Ngeni village in Blitar Regency, East Java on 29 January 2006. 37 In-depth interview in Ngeni village in Blitar Regency, East Java, 31 January 2006. 38 During the month of “suro”, or the silent month (February), Javanese custom prohibits the playing of loud music, circumcision, feasts and other community gatherings. The village head ensures observance of this practice. 39 FGDs with non-migrant families in Wiradadi village, Banyumas Regency, Central Java, 29 April 2006. 34 11 12 In Retrospect Most of the returnees believed that they were “sufficiently prepared” for overseas employment the first time they left Indonesia. They realized that they did not know enough of the language, and hardly knew host country laws and conditions and their rights. In the work place, social isolation was a problem due to restrictions by employers. There was a very low level of awareness and membership in migrant groups and associations and an even lower awareness as regards the Indonesian embassy/consulate/representative office. Pre-departure trainings provided by recruitment agencies were deemed helpful but there was too much emphasis on ‘obedience’ to foreign employers and nothing on ‘how to defend themselves’. Some mismatches in these trainings were noted.40 The waiting time or stay at the recruiter’s dormitory prior to departure varied from one week to nine months. Private recruitment agencies often recruit, train and keep a pool of available manpower even without a corresponding job order to the detriment of migrants as the longer the waiting period, the bigger the ‘debts’ accrue to these agencies. A number of returnees reported that they were not given training prior to departure. Most respondents worked 7 days a week and between 12 to 20 hours a day without additional compensation. Adjustment difficulties were homesickness, unfamiliar language, customs, climate and their employer’s insensitivity to their religious practices. Problems encountered were verbal/psychological abuse, physical abuse, sexual harassment, unpaid, underpaid and delayed wages. Only one respondent was able to approach the Indonesian embassy for assistance. There is also perception that the Indonesian Government does not care (‘tidak peduli’)41. Law No. 39: Some Initial Comments Law No. 39, or the Law on the Recruitment and Protection of Indonesian Overseas Migrant Workers, or Undang-Undang 39, is a major step forward in promoting the interests of Indonesian migrant workers. Prior to October 2004, labor migration was regulated through ministerial decrees which mostly consisted of provisions that regulated recruitment and did little to allow for a more integrated and effective approach to protecting migrant workers. The following comments and recommendations are put forward: First, the law must provide equal 40 In Blitar, one returnee was trained on babysitting but took care of an elderly in Taiwan. Another returnee from Hongkong was taught Mandarin instead of Cantonese. 12 13 protection to all Indonesian migrant workers regardless of immigration status in the host country. Existing studies on Indonesian labor migration show that undocumented workers constitute an equally significant number of Indonesian migrants. While the Ministry of Foreign Affairs established the Directorate for the Protection of Indonesian Citizens and Legal Entities to assist all migrants regardless of immigration status in the host country, it is limited to concerns on-site and does not address other concerns of nationals in distress.42 Second, given the realities in Indonesia, it is necessary to exercise stricter control and impose penalties (criminal liabilities as well) on erring recruitment agencies. There should be transparency in the renewal/extension of these agencies’ permits and these agencies should be made liable for the abuses of their middlemen, foreign counterparts and employers. Exorbitant placement fees, onerous repayment schemes and other pre-deployment concerns need to be further addressed by the law. Article 87 should be fleshed out. Timely provision of comprehensive, accurate, and gendersensitive information need to be emphasized beginning with community education and information programs. Specific programs and services at the community level are needed to achieve this end. Article 5 needs to be fleshed out in light of the decentralization law. Local governments and other service providers should be tapped to reach out to problematic returnees and make these programs and services accessible to them, particularly in the villages where a very strong culture of shame hinders ‘unsuccessful’ returnees and their families from approaching local authorities/service providers to avail of much-needed assistance. Given the culture of corruption, collusion and nepotism which the Yudhoyono government is trying to address43, there should be greater accountability of government officers and staff. There should be administrative sanctions for erring parties. Lastly, Law No. 39 should be more inclusive and actively engage NGOs, migrant groups and communities in promoting the interests of Indonesian migrant workers. Said groups have also proven to be effective in moving governments to act. 41This sentiment surfaced during most of the interviews in Blitar and Banyumas. Suara Merdeka (Indonesia), 20 March 2006. 43In December 2005, President Yudhoyono vowed to overhaul the immigration department in view of corruption cases reported at the Soekarno-Hatta (Jakarta) and Ngurah Rai (Bali) International Airports, and in Indonesian missions in Kuala Lumpur and Penang, Malaysia. 42 13 14 Conclusion Changes are taking place in Indonesian families and communities that have been touched by international labor migration. Female labor migration has more than just improved economic conditions of families. Women have broken from existing traditions and defied the odds. Despite unequal power situations in their places of work, they have not been disenfranchised.44 They have become empowered with the realization that it is possible for them and their families to live better. Their transformed selves bear eloquent testimony to what can be achieved through labor migration.”45 New work ethics and aspirations, openness to new ideas and other ways of life, changes in gender roles and relations and other socio-cultural developments were attested by the returnees themselves, their families and communities. Profound economic and socio-cultural changes that have transpired in Indonesia for the last three decades have accelerated these changes. Notwithstanding changes in many aspects of community life, effective social control mechanisms persist in ensuring continuity of local customs and traditions and closely held Javanese values (maintaining social harmony and order and knowing one’s place (‘tahui diri’). International migration will continue to be an attractive source of employment to most Indonesians as unemployment continues to rise. Remittances are positive and satisfying for households and communities but they are insufficient to realize national development goals. Remittances are a bonus, but not the main pillar of development. To maximize the financial, human and social capital gained abroad, public policy should continue to strive to minimize the risks and costs of international labor migration by instituting various interventions beginning with public information and community education programs, provision of timely and relevant on-site and reintegration services for migrants and their families, and stricter regulation, monitoring and imposition of stiffer sanctions for recruitment agencies. Law No. 39 is a major step forward in terms of promoting the well-being of Indonesian migrants. Many issues and concerns, however, need to be addressed. 44Filomeno Aguilar, 2002, Beyond Stereotypes: Human Subjectivity in the Structuring of Global Migrations in Filipinos in Global Migrations: At Home in the World?, F.V. Aguilar, ed., Quezon City: Philippine Migration Research Network and the Philippine Social Science Council, p.12. 45 Ibid, p.444. 14 15 References Cited Adi, R. 1996. The Impact of International Labor Migration in Indonesia. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Adelaide. Aguilar, F.V. Jr. (ed.) Filipinos as Transnational Migrants in Philippine Sociological Review, volume 44, nos. 1-4. January-December 1996, Quezon City: Philippine Sociological Society, 227 pages. ______________ 2002. Beyond Stereotypes: Human Subjectivity in the Structuring of Global Migrations, in F.V. Aguilar, Jr. (ed.), Filipinos in Global Migrations: At Home in the World?, Quezon City: Philippine Migration Research Network and the Philippine Social Science Council, pp. 1-38. Asian Development Bank (ADB). 2006. Workers’ Remittance Flows in Southeast Asia. Manila: Asian Development Bank, 248 pages. Ghosh, B., 2000, Return Migration: Reshaping Policy Approaches in B. Ghosh (ed.) Return Migration, Journey of Hope or Despair?, Geneva: International Organization for Migration/United Nations, pp. 186-226. Hugo, G. and A. Singhanetra-Renard, 1988, International Labor Migration in Indonesia: A Review, Mimeo. ________ 1995, International labour migration and the family: Some observations from Indonesia: Asia and Pacific Migration Journal, vol. 4. nos. 2-3, pp. 273-301. _________ 1998. Undocumented International Migration of Women in Southeast Asia: Major Patterns and Policy Issues in C.M. Firdausy (ed.), International Migration in Southeast Asia: Trends, Consequences, Issues and Policy Measures, under the South East Asia Research Program, The Toyota Foundation, Jakarta: Ciptamentari Saktiabadi. pp. 98-142. __________ 2004, International Migration in Southeast Asia since World War II in A. Ananta and E.N. Arifin (eds.), International Migration in Southeast Asia, Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, pp. 29-70. __________ 2005, Migration in the Asia Pacific Region. A paper prepared for the Policy Analysis and Research Programme of the Global Commission on International Migration. Geneva: Global Commission on International Migration. 62 pages. Accessed at http://www.gcim.org/inm/File/Regional%20Study%202.pdf on May 10, 2006. International Migration on Migration (IOM) website. Accessed at http://www.iom.int/jahia/Jahia/cache/offonce/pid/254 on July 27, 2006. Irwan A. Sangkan Paran Gender (The Role of Gender). Yogyakarta: Pusat Pelajar, 1997, pp. 208-209. Kanto, S. 1998. Migrasi Internasional Tenaga Kerja Wanita (TKW) Dan Pengaruhnya Terhadap Kondisi Sosial Ekonomi Rumah Tangga dan Masyarakat di Pedesaan: Studi Kualitatif Migran TKW di Desa Pagak, Kabupaten Malang, Jawa Timur (Female International Migration and its Socio-Economic Effects on Rural Households and Communities: Qualitative Study of Female Migrants in Pagak village, Malang Regency, East Java). MA. Thesis. Universitas Brawijaya, Malang. 70 pages. Law No. 39 on the Recruitment and Protection of Indonesian Migrant Workers (also known as Undang-Undang Nomor 39 Tentang Penempatan dan Perlindungan Tenaga Kerja Indonesia di Luar Negeri) Ministry of Manpower and Transmigration website accessed at www.tki.or.id. Also at http://www.nakertrans.go.id. in July 2006. 15 16 Muzakka, M., Suyanto and C. Kepirianto. 2003. Mobilitas Internasional Tenaga Kerja Wanita: Studi Perubahan Sosial Ekonomi Rumah Tangga Tani Desa Banjarsari Kecamatan Nusawungu Kabupaten Cilacap (Female International Labor Mobility: A Study on SocioEconomic Change in Agricultural Households in Banjarsari village, Nusawungu District, Cilacap Regency). A Report. Universitas Diponegoro, Semarang. 60 pages. Nagib, L., H. Romdiati, M. Noveria, T. Handayani, Daliyo, D. Asiati and S. Sunarti. 2001. Studi Kebijakan Pengembangan Pengiriman Tenaga Kerja Wanita ke Luar Negeri (Policy Study on the Development of Deployment of Women Overseas). Jakarta: Office of the State Minister for the Empowerment of Women in cooperation with the National Research Center on Population and Labor, Indonesian Institute of Sciences, 91 pages. Sri Rum Giyarsih and U. Listyaningsih. 2002. Dampak Non-Ekonomi Migrasi Tenaga Kerja Wanita ke Luar Negeri di Daerah Asal (Non-Economic Impact of Female Labor Migrants). Research Report. Center for Women’s Studies, Research Institute. Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, 49 pages. Suara Merdeka, 2006. “Jenazah TKW Yuniarti Langsung Dimakamkan” (Remains of migrant worker Yuniarti to be buried), March 20, p. 28. Sukamdi, Setiadi, A. Indiyanto, A. Harris and I. Abdullah, 2001, Country Study 2: Indonesia in Supang Chantavanich et al (eds.), Female Labour Migration in Southeast Asia: Change and Continuity, Bangkok: Asia Research Centre for Migration, Institute of Asian Studies, Chulalongkorn University, page 128. Suyanto, M. Muzakka and M. Hermintoyo. 2001. Peran dan Kemandirian Tenaga Kerja Wanita dalam Rumah Tangga: Studi Kasus Tenaga Kerja Wanita di Desa Pemanggulan di Kecamatan Pengandon, Kabupaten Kendal” (The Role and Independence of Women Migrant Workers in the Household: A Case Study of Women Migrant Workers in Pemanggulan village, Pengadon District, Kendal Regency). Center for Gender Studies, Universitas Diponegoro, Semarang. 66 pages. Yayasan Pengembangan Pedesaan (Rural Development Society). 1992. Trade in Domestic Helpers, Indonesia (With a micro study from East Javanese Domestic Helpers). Final Report. Rural Development Society. 16