PCC Stress Injury Report - Paramedic Chiefs of Canada

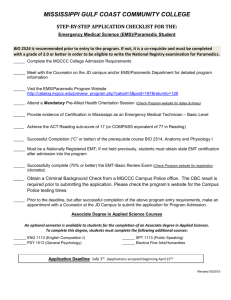

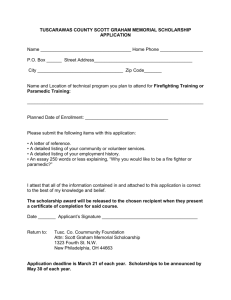

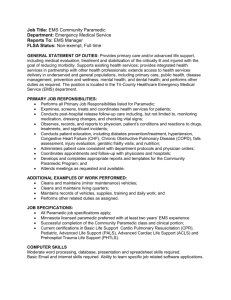

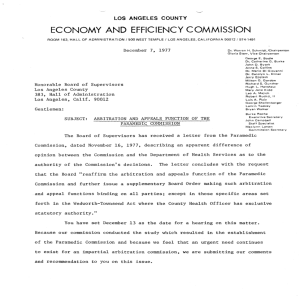

advertisement