Module 5 Participatory Technology Dissemination

advertisement

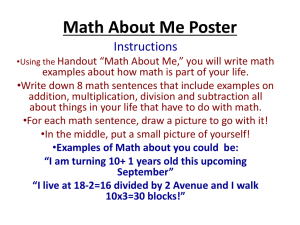

National FSA Training Module 17 Module 17: Produce user-friendly outputs Produce user-friendly outputs Rationale: Many researchers consider trial reports as the main output of research. However, research will not have an impact without addressing the dissemination of research results. One zonal director in Tanzania summarised this as follows: "The investment made in the research activity should be seen as an imprest: if the results are not presented to the client or not to the client satisfaction, then the imprest is not settled." Research has a key role in the development of suitable information packages. The only real justification for agricultural research is the adoption of research interventions by farmers and other technology users. Objectives At the end of this module you will: 1. Understand the need for production of user-friendly materials 2. Be able to determine the best partners and best media for dissemination of research findings 3. Have prepared a fact sheet 4. Understand what makes a good leaflet or poster and you will be able to apply those guidelines to the dissemination of your own research findings 5. Have reviewed basic extension material Content 17.1 Determine information needs and research messages 17.2 Choice of dissemination partners 17.3 Choice of dissemination media 17.4 Producing fact sheets 17.5 Development of messages 17.6 Illustrations 17.7 Posters 17.8 Review and testing of extension material 1 National FSA Training 17.1 Module 17: Produce user-friendly outputs Determine information needs and research messages Information that is available from Tanzania suggests that the use of improved agricultural technology is not a common practice. For example, in the agricultural census of 1994/1995 it appeared that out of every ten farmers only three use improved seed; two use chemical fertiliser; six receive advice from extension agents; eight own an axe and one owned a plough (Limbu, 1999). One of the reasons for poor adoption has of course been the lack of relevance of technologies, e.g. where evaluations focus on yield improvements rather than economic benefits or early maturity or where results assume external inputs that are too expensive (Kajimbwa, 2002). Extension and farmers cannot use the technologies developed. Another major reason has been that in many countries technologies remain on the shelves, simply because extension and farmers are unaware of their existence (Eponou, 1995). For example, the main channels for dissemination of research results in Tanzania are normally progress reports presented during an IPR (which do not have sufficient information on the technologies), annual reports (often not produced at all) and journal articles or workshop papers (which are not accessible to extension agents). Too often researchers consider links with extension and farmers supplementary to their normal research workload. Quite a number of researchers still think that it is up to the extension agent and farmer to come to research, get the technology, transfer it to farmers, and provide feedback if they have. Demand-driven research has to show a strong output orientation in order to increase client appreciation and the impact of research. Research findings need not only to be published (see Module 16) but also have to be available in a form that clients can easily access. In for example a survey from Kenya, farmers indicated that their most pressing information requirement which was not being adequately addressed was information on technical details of farming (e.g. chemical application rates, how to manage late blight in potatoes, where to get certified seed, the most appropriate varieties for a given location, housing and management of livestock, etc.) (Rees et al., 2000) In the private commercial sector market research pays considerable attention to consumers’ needs for, and perceptions of new products. This information is used to develop products which are likely to be a commercial success, and to develop effective communication strategies for marketing these products. This type of research is much less common in agriculture and extension than in business, partly because government officers will not lose their jobs if they do not ‘market’ their ideas effectively. Furthermore, there are often insufficient resources for good market research. Effective information flows from extension agents to extension managers and researchers, and from researchers to extension and farmers, can largely make up for this deficiency. Quarterly workshops as organised in Tanzania could be used for this specific purpose but often remain focused on a one way transfer of information. Joint workshops of researchers and stakeholders as organised in the Lake Zone, can also be used to assess client information needs and make an inventory of technologies available from research. The latter is called a gap analysis between research and development options, and farmer practices (see Box 17.1). 2 National FSA Training Box 17.1 Module 17: Produce user-friendly outputs Gap analysis in the Lake Zone In the Lake Zone in Tanzania researchers, change agents (public and private) and farmers systematically analysed recommendations for different commodities (e.g. maize, coffee) and factors (e.g. soil fertility management). The recommendation gap analysis workshops focused on the state-ofthe-art in relation to formal (research) and farmer knowledge. The workshops aimed to: 1. Provide a basis for a comprehensive loose-leafed updateable extension manual for different agroecological zones 2. Develop a basis for reorientation and priority setting of research programmes Fifteen workshops were organised and characterised by: 1. Technology gap between research, extension and farmer practice was analysed and discussed for each relevant farming system 2. If possible farmer knowledge was used: use of local names, farmers assessment and selection criteria, and farmer priorities for development 3. A similar format was used for all workshops also to allow the information to fit a loose-leafed extension manual for each farming system zone. Extension administrators and researchers are often worried about delays in farmers’ use of the research findings. They want to know how the adoption of relevant innovations can be accelerated (Van den Ban, 1996). Studies have clearly demonstrated the extensive delays that occur between the time farmers first hear about favourable innovations and the time they adopt them. It often takes years (and sometimes decades) for the majority of farmers to adopt recommended practices. Researchers have naturally been keen to find out what happens during this time (Van den Ban, 1996). The latter will not be discussed here but will be dealt with in Module 18. 17.2 Choice of dissemination partners It may be necessary to develop different messages to meet the needs and the situation of each category of adopters. This approach is frequently used in marketing where it is called “market segmentation’. Table 17.1 gives an example from a workshop in Kenya where target groups were segmented. Table 17.1 Example from Kenya: Dissemination partners for crop protection technologies Partner Interest/objective Strength Weakness Farmers Healthy, productive crops Teaching farmers better crop protection Help members Direct beneficiaries Inadequate information and resources Lack knowledge, lack motivation Not easily accessed Extension Growers associations/ CBO's NGO's Practical training Grass root presence, group approach Community contacts Traders Community development Sell chemicals Chemical companies Sell chemicals Expert knowledge, global influence Pesticide board Effective chemicals, minimal toxicity Knowledge, authority, existing communication channels Grass root presence Source: Scarr et. al. (1999) 3 Other agenda Lack technical knowhow Want to sell even when chemicals are not needed Rigid, discourage innovation National FSA Training 17.3 Module 17: Produce user-friendly outputs Choice of dissemination media Researchers and research institutes play an important role in seeking options for subsequent increased dissemination of information. Dissemination should (1) target primary partners and primary stakeholders, or (2) aim to scale up research results to the full mandate area. For the first, the following options have been tried in various zones in Tanzania: Debriefing meetings for farmers and extension staff who participated in on-farm experiments at the end of each season Field days on-station and on-farm Permanent exhibitions within research institutes Annual meetings with all stakeholders such as the annual stakeholder meetings in the Lake Zone In the second approach change agents are being targeted for scaling up the results. The following options are used: Technology markets: A technology market is a meeting where researchers present technological options through short presentations, and demonstration of implements, posters and pictures. Farmers who are interested in testing a particular option can register themselves. Researchers make appointments for follow-up visits to discuss experiments and options. This is an improvement on the situation where researchers select farmers. Farmer Extension Groups (FEG): FEG's are groups of farmers that are working with extension in the verification of recommended messages developed in the same or a similar FSZ by an FRG. The number of FRG's is normally limited, while the number of FEG's is larger than the number of FRG's but smaller than extension contact groups. FEG's remain in close contact with FRG's through extension staff and farmer visits in order to get technology feedback. During field days in the FRG's FEG members are invited to assess technological options for possible testing in the FEG. Use of printed and mass media We will further discuss this last option. The manner in which research messages are packaged should encourage adoption of improved practices. Researchers and clients have to agree on message formats and analyse options for effectiveness and efficiency. Media options are many (see table 5.2) but need to be used carefully, linking them to target group characteristics, characteristics of the message that needs to be conveyed, and resources that are available. People in countries like Tanzania become aware of innovations by talking to friends, neighbours and extension agents. This may be attributed in part to social structures and customs in these societies, and in part to high levels of illiteracy and few outlets for printed media in rural areas. In both industrial and less industrialised societies potential users make their decision to try or adopt innovations following personal discussions with people they know and trust (Van den Ban, 1996). 4 National FSA Training Module 17: Produce user-friendly outputs Table 17.2 Media analysis Media Strength Weakness Leaflet/ brochure Poster Stores information, can be used repeatedly Reaches illiterates, good for raising awareness Reaches illiterates Not accessible for illiterates Field day Radio Filmstrip/ slide series Video Reaches many people, raises awareness, changes attitudes Reaches illiterates, develops skills, can be shown in rural areas Raises awareness, changes attitudes, develops skills Raises awareness, changes attitudes Drama/ songs/ storytelling Source: adapted from Scarr et. al. (1999) 17.4 Short-term access to information Only few people reached at any time, information cannot be stored Expensive, one-time broadcasts, not suitable for skill development Relatively cheap if processing lab is available Expensive, limited access in rural areas One-time performances, not suitable for skill development, cannot last longer than half an hour Producing fact sheets Every research activity needs to be summarised in a fact sheet be it from on-station of on-farm research. A fact sheet summarises research results and technical information on a selected topic. The fact sheet provides an overview of relevant facts and data from the experiment or survey, and may be supplemented with data from literature. The fact sheet enables reviewers to assess the reliability of results and recommendations. A fact sheet can serve as a basis for developing any kind of extension material, be it a leaflet, brochure, poster, radio message, slide series or song. In the justification you quantify and qualify the problem or opportunity, for example: quantify losses and infestation rates due to an insect pest, list disadvantages of a conventional technique, list causes of a decline in yield or causes of incidence of livestock diseases. The background gives the reader all the necessary experimental data or survey results needed to assess if the recommendations have enough scientific justification. The background summarises all data that the target group may need to compare the new technique with the conventional technique, e.g. quantification of yield increase, percentage insects killed, extra labour involved, extra costs, economic gains, possible constraints or conditions for adoption. Who is likely to benefit from the technique and who could use it. What questions may the target group raise and ensure that those are answered. Overall the background should encourage the target group to adopt the technique and preferably offer them multiple choices. The recommendations should follow from the data given in the background. These recommendations should be simple, flexible (offering a basket-of-options) and targeted (e.g. for household classes, AEZs, LUTs, gender or growing seasons) and in a chronological order. The information given in a fact sheet should enable a reviewer to assess or evaluate the correctness of the information provided. Hence references have to be given for all information. and have to be specific, including authors names and the year (see table 5.1). In your fact sheet you need to make sure that: (1) The message is complete. Problems that readers are likely to encounter in the field concerning the message need to be covered. 5 National FSA Training (2) (3) Module 17: Produce user-friendly outputs The message is specific and should cover who can do it, where it can be done, and when it can be done. The recommendation should be given in such a way that it increases the readers’ understanding of the technology, and improves their skills. The advantages of a certain technology as compared to the conventional technique are mentioned, e.g. line planting may increase labour at planting but reduces amount of seed used and makes weeding easier. Table 17.3 Example of a fact sheet: cereals dry season stalk management Step Description Evaluation Justification losses on zonal level not known Cereal stemborers are the main pest in maize and sorghum in the Shinyanga Region; average losses of 30% (maize), abundance of up to 87% infestation rate (maize and sorghum) Main species: Chilo partellus, Busseola fusca Stemborers diapause as larvae in the left over cereal stalks over the dry season Main carry over of stemborers from season to season is in dry stalks Stemborer adults are mobile over short distances (up to 15 km radius) Background Number of diapausing stemborers in wild (Hyparrhenia data rufa, Typha spp.,etc) and other cultivated hosts (sugarcane, elephant grass) is negligible Maize stalks are used as fodder and the fields are usually cleared Sorghum stalks are left standing and host many diapausing larvae Diapausing stemborers are situated usually in the upper parts of the stalk, the lower part is often hollow and/or eaten by termites Chopped stalks are to at least 95% free of diapausing stemborers (after 6 weeks) Chopping sorghum stalks takes about 12 person hours per ha with a handhoe, 18 personhours with a panga Farmers and Bwana Shambas are usually not aware of diapausing stemborers in stalks Recommen Make farmers aware of stemborer larvae in dry stalks dation Cut dry cereal stalks (mainly sorghum) on the base with a handhoe Leave cut/chopped stalks on the field as mulch (protection against erosion, organic material) Do cutting until approximately 15 September Or feed stalks to livestock (maize) Invite the whole village to do stalk management Source: Braun and Kolowa (1996) 17.5 survey data survey data survey data literature survey data survey data survey data survey data experimental data Development of messages Most researchers have limited capacity to develop extension material. In that case messages should be developed jointly with extension staff, and research capacity needs to be strengthened. In Tanzania and Kenya this has been done through e.g. workshops where researchers work together with technical editors, graphic designers, illustrators, translators, and extension staff. Some guidelines for message formulation are given in Box 17.2. 6 National FSA Training Box 17.2 Module 17: Produce user-friendly outputs General guidelines for leaflets, brochures or posters A clear, simple title that motivates and summarises the main point of the message, e.g. "Avoid potato bacterial wilt!" or "Stop Newcastle disease". A good title has 4-5 words of which 1 is a verb. Short introduction describing the problem Focus on one idea only Include technical details of the message, including illustrations and drawings Use the Farming Systems Approach, i.e. use a basket-of-options approach rather than blanket prescriptions Give sources of additional information Include acknowledgements/ Published by / Designed by / Printed by / Keep it very brief and concise: a leaflet has maximum 4 pages, a brochure not more than10 pages Source: Scarr et. al. (1999) Fact sheets are the basis for developing any kind of written text, e.g a leaflet or poster. You can design a variety of extension materials, each of them serving a specific purpose but following different story lines. The following are some examples: The “how-to-do-it” story: here you show how to carry out a technique or method step by step. The steps have to be shown in chronological order. The technical story: here you use one character or more characters (typically a farmer and extension agent) to show techniques and operations. The reader can identify with the character who successfully adopts or carries out the new techniques. The story shows how the characters benefit from the techniques followed. The motivational story: this story gives credibility to new ideas. The readers follow characters like themselves who also seek opportunities. The characters usually take up new methods for working and improved production techniques. Example: Better chickens, more profits! Cartoons: they present a subject in an entertaining way, and still teach important concepts and practices. Cartoons can make the information more accessible for farmers but need the help of an artist for making the illustrations. Table 17.4 Characteristics of cartoons and text attracts readers requires reading skills can deal with complex issues more details can be included interpretation of message unpredictable easy to read suitable for flexible recommendations Cartoons Text XXX XX X X XXXX XXX X X XXX XXXX XXX X XX XXX It follows from the table that your decision for cartoons or text should be guided by (1) your target group and (2) the content of your message. Next, the text should be organised logically. This follows the following order: 1. Problem or opportunity: How can the target group recognise the problem and why does the problem occur (explain why it happens). When describing an opportunity include what the conditions for adoption are, e.g. cash, labour availability in a specific time of the year, inputs, etc. 2. Solutions: This describes a range of options and answers questions such as what should be done, how it should be done and when it should be done. 3. Possible gains: What are the advantages of the new technique, does it reduce labour or drudgery, does it increase income? 7 National FSA Training Module 17: Produce user-friendly outputs 4. Necessary inputs: Where can the target group get seeds, chemicals or additional advice. Example: A large fertiliser company had been marketing its products for years on the basis of the chemical contents, with names indicating the ratio of nitrogen, phosphorus and potash. Then the sales section of the company requested the help of a rural communication specialist who interviewed farmers. The marketing strategy was changed to stress the end use of fertiliser rather than its composition. Each type of fertiliser was advertised on the basis of how, when and where it should be used and what results could be expected. Box 17.3 gives a range of guidelines as to how to make sure that your text is simple and can be understood easily by the target group. Box 17.3 How to ensure that your text is simple address the reader directly as “you” use active verbs: “Improve your yields” instead of “Yields can be improved by…” emphasis action, e.g. describe how to recognise a pest rather than a description of its biology advocate change, e.g. “Keep aphids of your beans” explain why the recommendation is better than the conventional practice give options, e.g. one with low cost and one with high cost so that farmers can make their own choice use short sentences (i.e. on average 11 words per sentence) and simple, short words avoid Latin names, jargon or technical terms, instead use local names for diseases, varieties etc. avoid uncommon or specialist words give quantitative results including economic data if possible use farmers’ units, e.g. feet, acres, bags use locally available measures, e.g. bottle-tops, debe, matchbox avoid or explain acronyms avoid repetition do not ask the reader to refer to earlier or later text do not use different words to mean the same thing Source: Scarr et. al. (1999) 17.6 Illustrations Illustrations make information accessible. A striking illustration is worth countless words. Illustrations may be drawings or photographs. All illustrations have to be clear. People should be able to identify with the illustrations and should recognise the symbols that are used. For example: A house should resemble a house most people live in and not e.g. a town house. A female farmer should wear a kanga and not dress as if she is on her way to a party. Illustrations should show clearly what the subject is, and they should not contradict the text. Preferably each picture should serve to illustrate only one thought and should not show unnecessary details. Illustrations can be used in four ways: 1. To examine techniques step-by-step from beginning to end. 2. To show the passage of time, for example one illustration where a farmer applies fertiliser and an illustration next to it that shows the field at the end of the cropping season. 3. To contrast a problem with a solution, for example an illustration of a field that is not managed well with an illustration of a field that is managed according to the message content. 4. To visualise numbers, e.g. one farmer harvested 10 bags and another farmer harvested 35 bags. 8 National FSA Training 17.7 Module 17: Produce user-friendly outputs Posters Posters are large and colourful visuals that can only carry short, catchy messages and present one central idea. The visual content of the poster must reinforce the message. Posters are meant to be seen by a passing audience. This means that they have to be designed in such a way that they attract and hold the attention of the audience long enough to convey the message. Posters are put at places where they can be easily seen from a reasonable distance. The following is a general guideline to designing a poster: 1. Decide the size of the poster. This should be determined by (1) the card size that is available, (2) possibilities for multiplication (printing or photocopying) and (3) the intended places of exhibition. Posters should be at least A3 size. 2. Elaborate a story line or a table of content. This should be guided by the fact sheet and should focus on the content of the message. At this stage text needs to be structured and there should be a clear distinction between what information is essential and what information is of secondary importance. A poster can only cover one or two blocks of information. 3. Posters use visuals to illustrate and reinforce the message. Bear in mind that the viewers who will read the poster are passing by and will not give much time to reading text. 4. Make a sketch plan of the poster, drawn to scale, and decide how many illustrations and how much text can fit into the allotted space. Display the information in such a manner that it is clear for viewers whether they are to read across the poster or down. The blocks of information can be numbered to help viewers find their way through the information on the poster. 5. Viewers should be able to read your poster from a distance. Thus the size of your lettering and the type of letters (font) is important (See Box 17.4). Box 17.4 Guidelines for lettering on a poster To facilitate reading you should choose a simple typeface: Times Roman or Arial. Use capital letters only for the initial letter of the first word of a sentence, or for words that are usually written in capitals. Do not use capital lettering elsewhere. Text that consists of capitals alone is much less legible, even at a distance, than lower-case letters. People should be able to read the heading of your poster from up to 5 m away. Make capital letters in the title of your poster 25-40 mm high, with lower case letters of the appropriate size (font size at least 100 pt.) Sub-heading capitals should be 10-16 mm high and a lower case ‘x’ should be 6-10 mm high. This means a font size of 48-72 pt. The main text of your poster should be readable from a distance of 1 m. This implies that capital letters should be 6-8 mm high, with a lower-case ‘x’ for example 4-5 mm (font size 26-36 pt.). A poster has to be attractive in order to motivate people to stop and read the poster. An attractive lay-out will greatly facilitate the dissemination of the message. This normally results in: Using colour: strongly coloured card makes a good background for text in black and attracts attention; A catchy title that reflects the theme, leaving out any unnecessary words to make the title as short as possible, e.g. “Kill weevils”; Clear illustrations that people can identify with. Posters should be recognised as coming from one institution and would list the following: Acknowledgements [name of institutions or projects that financed the activity] 9 National FSA Training Module 17: Produce user-friendly outputs Published by [authors should not be mentioned by name, instead use the name of the institution] Year of poster preparation, publication Designed by [name of the artist] 17.8 Review and testing of extension material Once you have drafted a leaflet, brochure or poster the material needs to be reviewed by peers, extension staff and farmers. A standard review form will guarantee high quality reviews (see handout distributed). After finalising the review you need to test the material. The objective of testing is to: determine in how far the target group(s) understands the written text and the illustrations; identify users’ opinions of the relevance of the message itself and its applicability to their situation; determine if the presentation and lay-out are attractive; assess if the message encourages adoption of the improved practices. Identify the group that you will test the material with (see Box 17.5). The category of people that you interview should depend on the content of your message. In general you should select a wide variety of participants e.g. based on age, gender, or tasks with respect to the message. Select at least ten people. Box 17.5 Possible stakeholders for pre-testing extension material Farmers Extension staff Government, parastatals Agri-business Community Based Organisations Researchers men, women, youth government, non-government, church organisations, farmers associations, Farmer Training Centres Coffee Board, Cotton Board, TPRI, Development Authorities, local administrators Traders, stockists, seed companies, chemical companies, general suppliers, vets, millers, processors women groups, farmer groups, schools national and international research centres, universities, NGOs Source: Scarr et. al. (1999) The general procedure for testing of written material is as follows: In the introduction participants are presented to each other, the testing objectives and procedure are explained, and it is explained why these participants were selected. Each participant receives a leaflet, brochure or poster and is asked to read it. Each participant may add her or his comments with question marks in the margins. The team observes the time that is required by participants to read through, and also observes if there is any specific pages or drawings that seem to take more time for the participants to understand. During an individual or group interview the following are discussed: 1. What is according to you the main message that is described here? 2. What questions did you ask yourself about this message before reading this? What questions do you think will be asked by others? Does this material answer these questions satisfactorily? If not, what information be added? 3. Is there anything new in this message that you did not know before? If so, what elements are new to you? 4. How big is the demand for this information in your area? 5. After reading this, are you convinced that the message as it is presented here is worth disseminating? If not, why not? 10 National FSA Training Module 17: Produce user-friendly outputs Is the information practical for you or others? Are there any words that are difficult to understand / not clear? Are the measurements and units shown in a way that you or other farmers can easily understand them and apply them? 9. What group of farmers will be interested in this message and would be able to use the information (e.g. according to gender, level of education, resources: male/female, rich/poor)? Who will not be interested, why not? 10. Are the illustrations clear and easy to understand? 11. Are there any elements in the illustrations that you are unfamiliar with (e.g clothing, activities)? 12. Are the illustrations attractive? 13. If we would charge TShs.150 for this leaflet, brochure or poster, how many people in this area would buy it? (none/ few/ half/ many/ all) 14. Other comments and suggestions for improving the material? 6. 7. 8. During testing the team should remember that they are testing the material and not the readers or audience! The readers or audience are always “right”. If they get a wrong impression or do not understand, it is the material that needs to be improved. After testing, the results are discussed and compiled in a short report. This report is the basis for final editing. Text may need to be added, language corrected and illustrations improved. Locally generated technologies often require formal approval before messages can be disseminated. Procedures and regulations need to be reviewed before technologies are released. The analysis should focus on existing legislation (including by-laws), bio-safety regulations and national rules within the Ministry of Agriculture and the research organisation. While messages concerning agronomic practices, use of fertiliser and pesticides, are approved locally, the use of different inputs is normally approved at the national level. Even though it is important that an institute formally endorses messages, it is equally important to avoid blanket recommendations and accept the possibility of several different, overlapping messages for the same commodity or enterprise for different zones/regions and/or target groups. 11 National FSA Training Module 17: Produce user-friendly outputs Key terminology Extension or to extend This means that an innovation, special information or perhaps a governmental instructions is made known among the farmers. Innovation An innovation is an idea, method, or object which is regarded as new by an individual, but which is not always the result of recent research. Linkages This concept implies the communication and working relationship established between two or more organisations pursuing commonly shared objectives in order to have regular contact and improved productivity. Technology Knowledge and techniques 12 National FSA Training Module 17: Produce user-friendly outputs References Ban, A.W. van den, and H.S. Hawkins (1996). Agricultural Extension. Blackwell Science, Oxford. Braun, M. and H. Kolowa (1996). Technical notes. IPM project, Shinyanga. Eponou, T. (1995). Linkages between Research and Technology Users: Some issues from Africa. Briefing Paper 30. ISNAR, The Hague (Downloadable from ISNAR web-site) Kajimbwa, M.G.A. (2002). Locally Integrated Extension Services in Tanzania: An effective organization for service provision in the Local Government Authorities. Paper presented during the Workshop on the Future Roles of Research and Extension Services in Tanzania, 16-17 May 2002, Dar es Salaam. MAFS, Tanzania. Limbu, F. (1999). Agricultural technology, economic viability and poverty alleviation in Tanzania. Paper presented at the Structural Transformation Policy Workshop, 27-30 June 1999, Nairobi, Kenya. ECAPAPA, Tegemeo Institute and Michigan State University. Rees, D., M. Momanyi, J. Wekundah, F. Ndungu, J. Odondi, A.O. Oyure, D. Andima, M. Kamau, J. Ndubi, F. Musembi, L. Mwaura and R. Joldersma (2000). Agricultural knowledge and information systems in Kenya: Implications for technology dissemination and development. AgREN Network Paper No. 107. ODI, London. (Downloadable from the ODI web-site) Scarr, M.J., D.J. Rees, J.N. Chui, R. Joldersma and E.P. Hoare (1999). Packaging and dissemination of research messages. In: Sutherland, J.A. (ed.) (1999), Towards Increased Use of Demand Driven Technology. KARI and DFID, Nairobi, Kenya 13 National FSA Training Module 17: Produce user-friendly outputs Further reading Van den Ban, A.W. and H.S. Hawkins (1996). Agricultural Extension. Blackwell Science, Oxford. Sutherland, J.A. (ed.) (1999). Towards Increased Use of Demand Driven Technology: Volume 1, pre-conference mini-papers prepared for the KARI/DFID NARP II project, 23rd-26th March 1999. KARI and DFID, Nairobi, Kenya. Web-site Overseas Development Institute: www.odi.org.uk Web-site Agricultural Research and Extension Network: www.odi.org.uk/agren Web-site International Service for National Agricultural Research: www.isnar.org 14 National FSA Training Module 17: Produce user-friendly outputs Guidelines for trainers Session 1: Introduction to output production and fact sheets Time 08.30 - 08.35 08.35 - 08.45 08.45 - 09.05 09.05 - 09.15 Topic Introduction Inventory of information needs and research messages Inventory of dissemination partners 09.15 - 09.25 09.25 - 09.35 Inventory of dissemination media Distortion of information Background of a fact sheet 09.35 - 10.30 Develop a fact sheet 10.30 -11.00 11.15 - 12.45 11.45 - 12.05 Tea/coffee break Develop a fact sheet Tomato leaflet 12.05 - 12.25 Develop a message Description of activity Present programme and objectives Present differences with private commercial businesses Example gap analysis workshops in LZ Discuss dissemination partners for different messages using examples from control of cassava CMD, and MPT, and their strengths and weaknesses. Divide group in 2 in big hall and ask them to quickly inventorise individually. List in plenary after 10 min. Brainstorm on different extension media, discuss strengths and weaknesses Exercise spread one sentence through 40 people Present the characteristics of a fact sheet, and the do's and don'ts. Show an example. Group assignment: 6 groups each develop a fact sheet for 1 topic in the group Plenary presentations of group work Exercise: participants go through the leaflet individually for 10 min. Plenary of 10 min. to list the mistakes Discuss story-lines Logical structure of text How to keep your text simple 15 Materials needed Transparencies Transparencies Transparency with question Compile answers on flipchart On flipchart in plenary session One flipchart with the sentence on Transparencies 45 blank fact sheets 45 copies of tomato leaflet Flipchart Transparencies Example how-to-do: Make soya-products Example motivational: Better chicken National FSA Training 12.25 - 12.40 Module 17: Produce user-friendly outputs Illustrations Discuss what makes a good illustration Transparencies Example clarity: man blackening pole Example soya Example problem/solution: milk bottles Example numbers: cash earned, harvested bags Materials needed Transparencies Examples bad and good titles Session 2: Poster and leaflet production Time 14.00 - 14.10 Topic Titles Description of activity Discuss bad and good titles for leaflets and posters 14.10 - 14.30 Posters Plenary discussion on clonal coffee poster and processing of banana poster: what is good and what is bad Do's and don'ts for posters 14.30 - 15.00 Posters 15.00 - 16.00 Review of extension material 16.00 - 16.30 16.30 - 17.00 Tea/Coffee break Review of extension material Testing extension material 17.00- 17.30 Assignment: 8 groups (2 receive the same leaflet) review the leaflet using the review form and the original fact sheet. Examples: coffee and banan poster Transparencies Example: Capital and lower case 15 copies of leaflets: HH categories, banana wine, goat management 15 copies of the fact sheets for above leaflets 45 copies of review form Presentation of review results: 10 min. for 2 groups. Discuss testing guidelines 16 Transparencies Examples: testing reports of 3 leaflets (HH categories, banana wine, goat management)