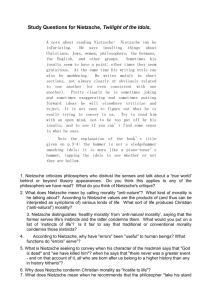

Paul Carls

advertisement

1 Paul Carls 8 May 2009 Nietzsche Seminar The Meaning of Gefahr in Nietzsche’s Oeuvre Introduction/Summary The text for this seminar is an entry into the Nietzsche Dictionary by Benedetta Giovanola concerning the word Gefahr. The article gives an outline of the meanings of this word that Nietzsche uses and in what context in order to better understand what Nietzsche means when he discusses Gefahr in his works. The article is broken into six different categories, and the majority of the content is a series of exerts taken from Nietzsche’s books in which he uses the word Gefahr. The main goal of the article is to employ a systematic presentation of the word Gefahr in Nietzsche’s works in order to understand better Nietzsche’s philosophy, and I believe that the article succeeds largely in this effort. The first category of the article discusses information about the use of Gefahr in Nietzsche’s, oeuvre, taking note of how many times and where the word is used and of the semantic field of Gefahr. The second category is a table of contents concerning the thematic and structure of the passages the article cites from Nietzsche’s work. In other words, it is the table of contents for sections 3 and 4 which include the cited passages. The third and fourth categories are the parts of the article that reproduce exerts of Nietzsche’s work in which the word Gefahr is used. The first section (1) of exerts falls under the title, “Was heisst Gefahr?” It is subsequently broken up into even more subsections, the first of which looks at Gefahr as “Etwas Negatives bzw. Passives” (1.1). This sub-section begins by examining the danger of the negation of life and the nihilistic outlook on life it brings with it. It is largely related to Christianity’s moral system, which seeks to repress the natural aspects of life as much as possible. The idea of a conservation of life, of the conservation of something already existing, as opposed to its growth, is also listed as a danger. Nihilism is also described as “Die Gefahr der Gefahren: Alles hat keinen Sinn.” (I.1.1.4) The article then discusses the danger in the loss of the interior form and organization of an individual, with a concentration instead on the content. Namely, once an individual’s belief, the content, is gone, their inner form, or constitution of spirit, will not be strong enough to survive. The danger of the infinite (I.1.4.2) is also 2 discussed in the article, Nietzsche claiming that modern man is like someone in a horse carriage who has let go of the reins. Next is mentioned Nietzsche’s belief that modern man is overwhelmed by the excessive excitation of ‘Nerven- and Denkkräfte’ and has become neurotic as a result. (I.1.4.3) Next, excessive adoration of the past is discussed as a danger because it prevents the birth of new life. The article then mentions the danger of morality, or morality that does not strive for the creation of the strongest individual as being, again, “die Gefahr der Gefahren.” (I.1.5) The article next mentions the danger of the education system, which breeds individuals who are complacent and accepting of the modern culture. The second sub-section, “Etwas Positives bzw. Aktives” (1.2), investigates the positive and active aspects of danger. This section begins by looking at the ability to risk, and the overflowing of strength and confidence needed in order to do so. According to Nietzsche, “gefährlich leben” is the most effective way to the greatest enjoyment in life. (Beleg 14) Such a dangerous life in fact is a way of embracing and rejoicing in life, rather than holding it in contempt. The article then goes into the question of danger as it relates to science and knowledge. For Nietzsche the problem of science is the most dangerous. If one is to abandon the pride of humans with regards to science and truth, it will be necessary that science become more dangerous, i.e. that science gain the ability to abandon its faith in itself. Nietzsche also says that the only way to truly get to know someone is when our fate, or the fate of loved ones, lies in that individual’s hands. (Beleg 18) He also says that in the modern age there is too much safety and we are not able to truly know a human. The article then discusses how Nietzsche believes that the philosophers of the future are those who are able to live a dangerous life and risk everything as regards the truth. The article then mentions an interesting play on danger to the masses. In one instance, Nietzsche claims that the herd wants not only to make those who are dangerous undangerous, but to punish those individuals as well, and to get to the point where there is no more danger posed to the herd. On the other hand, Nietzsche says that the dangerous, free-thinking individuals need protection from precisely this harmful herd-morality. The article then goes on to describe danger as it relates to humanity as it is the “Noch-Nicht-Festgestellt” Tier. (1.2.3) The article mentions how even in Christian ideals 3 there is a love of danger and a feeling of power involved. It also mentions Nietzsche’s approval of the agon, which includes an aspect of danger. Next the article mentions Nietzsche’s concept of good and overabounding health as a way of being able to live in a dangerous and experimental way. It permits a freedom for adventure. Thus, Nietzsche advises people to live in an un-philosophical manner, in a foolish way even. This is because is allows the individual to continually risk themselves and “spielt das schlimme Spiel,” which is life itself. (Beleg 29) Next, the image of man as a thread between the animal and the Übermensch is mentioned. Man is not a goal, or an end-point in evolution, but merely something that must be overcome in order to achieve a higher state of existence. Nietzsche also claims that humanity is the sickest animal, precisely because it is always experimenting with itself and thereby making itself sick. Because humans are always thinking about the future they are never satisfied with what they are, which is a dangerous game that makes humanity profound and, yet, sick. Nietzsche also says that modern man wants above all else to be protected from the dangerous. With this protection goes a good deal of vivacity and life. Yet, the remedy for humans is thus revolutions and wars, indicating that within humanity there is constantly a need for danger. The end of this sub-section ends with a mentioning of the death of God. This is our greatest moment of danger, because it removes all sheltering identity for man, but it likewise has the ability to be the most courageous moment since it allows humanity to take responsibility for itself and to live dangerously. The second category concerns itself with investigating the content of danger. It is titled, “Was ist in Gefahr (Was wird Bedroht?) (II). The first sub-section, or the first thing threatened is “das Leben” (II.1) One way in which life is threatened by danger, is through history and historical reflection. An incorrect reflection upon and understanding of history by individuals would result in a decline of life. The second sub-category deals with the threats to humanity (II.2). The article then discusses the difficulties and dangers involved with the creation of moral values on the part of the individual. Not only are these morals by themselves difficult to create, but for the individual creating them, there is the danger of being ostracized from society. Morality itself, as the article demonstrates, is in any case formed according to the degree of danger the individual feels themselves in. Humanity is also threatened when there is a collapse of values. There is also a danger 4 for the individual who looks beyond the beliefs of the modern age, who hears their hollow clang in a universe void of God’s influence. This individual knows the fate of the West and feels great anguish in its presence. (II.2.2) There is also a danger when looking upon the suffering of another, because it reminds us of our own frailty. As for strong individuals, the sick are their greatest danger. For the excellent individuals there are also dangers, one of which is found in their constitution, the other of which is a result of the time period in which they are born. The Übermensch is also threatened in a similar way; by the small people. The third and final category of Nietzsche’s quotes deals with the sources of danger. It is aptly named, “Was ist die Quelle der Gefahr?” (III). The first source of danger is a morality that abstracts from reality. These “Carikatur des Menschlichen” are the most dangerous. (Beleg 43) Herd morality also poses a threat to the free-thinking individual. The morality of pity is also specifically mentioned as dangerous. It represents heard morality, the sickness and weakness of individuals, and also a deep nihilism and rejection of life, all of which have already been discussed. This makes it the most dangerous morality. Religion is also seen as a source of danger. Christianity for example is a religion that despises the world and has made it ugly. Monotheism, the belief in one, normal god (Normalgott) is also a source of danger, for it removes the plurality that is found in life and also within a group of individuals. (III.3.2) It breeds excessive conformity and equality among individuals. Another source of danger for a thinker comes from science, knowledge, or questions the truth, for it leads to the despair at the truth. This feeling is connected to science, and the will to truth. The will to truth is a dangerous will, because in the end it will lead to a questioning of itself, which will lead to the realization that there is no truth at all. History is a similar point of danger, which advances with its motto, “fiat veritas pereat vita.” (Beleg 58) This makes a strong statement, saying that truth is more important to life, and can be connected to the dangers that are found within the will to truth. Too much historical knowledge destroys our perceptions of the present and can be dangerous to the truth. Nietzsche also says that too much scientific knowledge is damaging to a people in the same way that too much money at once is. After this outline of Nietzsche’s use of Gefahr, Giovanola next discusses in the 5 fifth category of the article the etymology of the word Gefahr, tracing its German and Latin roots. She also investigates the use of Gefahr as it relates to the sublime, which includes a feelings such as majesty and danger, and to Greek tragedy, in which the hero must face danger. In the sixth and final category, Giovanola begins by discussing the philosophical significance of Gefahr in Nietzsche’s work and also how the concept has been treated and received by other philosophers. In the second half of this section, Giovanola investigates the traditional meaning of Gefahr and its utilization in Nietzsche’s works. She notes that Gefahr, in the early works, is used to designate something negative, whereas later on in Nietzsche’s works it comes to designate something more positive and affirmative. Nietzsche develops largely the latter of these two meanings, Gefahr being “strictly linked with individuals’ capability to run risks, to form and transform themselves in a neverending process of Selbstüberwindung and creation of future.” (12) This is also linked to the fact that man is not a defined animal, and therefore is either obliged to experiment with himself, or to passively search for security. Giovanola then discusses Gefahr as a ‘Lebensideal.’ Beginning largely in Morgenröte, this ideal develops itself and Gefahr is seen as a stimulus for life, urging humanity to continually improve and change itself. In this way, Gefahr gains ‘an existential connotation.’ (13) An important step in this process is the overcoming of morality. Within morality arises an interesting double-edged (maybe triple-edged?) sword. On one hand, morality is dangerous to life because it negates life and to the individual because it attempts to destroy the individual’s ability to view itself as individual and to force the individual to conform to a norm. Thus, morality, in seeking to reduce danger for the majority of the population constitutes a danger to life and to higher men. Thus morality can on the one hand be dangerous for some and on another hand be protective of a majority of people. Gefahr, on yet another hand however, can be used to subvert morality. By living dangerously and experimenting with itself, humanity is able to overcome the danger of morality. A similar two-fold stance can be seen with science as well. Science is dangerous to life if it becomes something secure, solid, and ‘pure.’ Gefahr can be introduced into science in order to shake this security and ‘Wahrheit um jedem Preis.’ (13) This allows for more creativity and an embracing of the Wille zur 6 Macht, which views being as becoming. Discussion 1) Our first point of discussion centered around the structure of the article itself and how exactly one could distinguish between different types and sources of danger. This is especially important as in the same text the word Gefahr has a plurality of meanings depending on the context in which the word Gefahr is used. Prof. van Tongeren mentioned that the structure of the article is such that the different meanings of the word Gefahr are torn apart and placed into their respective categories for the purpose of clarification. If for example in the same text there are different significations for the word Gefahr, the same text would be repeated in different sections of the article in order to separate out all of the different meanings and uses of the word. Others mentioned the risk of the loss of semantic meaning in this process, that by separating out different meanings for the Gefahr you risk losing the complexity of the context in which the word is mentioned. In other words, you risk performing a reductionism that simplifies too much the variety of meanings that Gefahr can have within a text. Prof. van Tongeren mentioned in connection the five meanings that he would ideally prefer in the article. They are; 1) the Grundbedeutung of Gefahr, or defining exactly what is Gefahr, i.e. risk, threat, what one fears; 2) What does danger consist in, or what is the constitution of Gefahr; 3) What is the efficacy of Gefahr, or what effects does it produce; 4) What is in danger; and lastly 5) What are the causes of Gefahr. 2) There were also numerous questions concerning how exactly it was possible to define Gefahr, and it was even noted that in the first section Giovanola does not present an adequate description of what exactly Gefahr is for Nietzsche. There were two options discussed concerning this question, a complex approach or a minimalist approach. Prof. van Tongeren noted that it was necessary to name the perspective of the individual viewing the danger and to understand the definition of Gefahr in this way. Thus, when we are discussing what Gefahr is, or means, it is necessary to begin with the different meanings of Gefahr in their particular context. The minimalist approach, on the other hand, searches for the unity of the meaning of Gefahr. It was noted in the discussion that this unity could constitute the fact that whenever there is Gefahr, there is always 7 something/someone that is opened to a threat, there is a risk and the possibility of losing something. It was noted that wherever there is someone who is wanting security and safety from one’s own Gefahr, there is another who is willing to open themselves up to the Gefahr. Gefahr, in this way, is always having some sort of threat, but this threat manifests itself differently in different situations. The threat to the individual can be the threat of a destroying or a weakening for example. Whenever an individual quits their security and opens themselves up in order to gain something else, there is always the risk that they will lose something valuable. In this way, if Gefahr is understood as a threat to existence, it might be the unity of Gefahr that would fit within the minimalist approach. Objections were raised, however, as some doubted whether the presence of a threat was sufficient to constitute something as a Gefahr. 3) We then discussed the fifth section of Giovanola’s article, especially the notion of the sublime. Some objections were raised at this connection between the historical use of the sublime and Nietzsche’s use of the word Gefahr. Giovanola noted that before Nietzsche the idea of Gefahr has no presence in philosophical literature, and so her discussion of the sublime in her article is searching for a connection wherever it is found. Some people wondered whether the connection is legitimate and if it actually aids the reader to understand what Nietzsche means with the word Gefahr. Florian made the point of bringing up the idea of Fortuna, fortune, chance, luck, that is used by Machiavelli in Principe. As he pointed out, it is a source of danger for the ruler of a state and its people. It is an un-calculable and un-predictable force that can bring bad fortune upon a ruler and its people. In this sense it constitutes a danger. As it relates to Giovanola’s sixth section, this discussion by Machiavelli demonstrates that there is a history of the use of Gefahr as a philosophical concept that could be included in her paper. 4) One final point of our discussion concerned Schopenhauer als Erzieher and the three types of Gefahr that Nietzsche mentions therein. Nietzsche mentions three types of Gefahr that are necessary for the creation of a genius; isolation, doubt of the truth, and a hardening of the intellect. Giovanola looks for the Gefahr that is used as the Lebensideal that develops the genius the most. We noted the difficulty inherent in the process, as there are three types of Gefahren, and the make-up of each of the Gefahr is difficult to 8 determine. There are, for example, Zeitgefahren, which are specific to the time period in which one lives, and also the Constitutiongefahren, which are inherent within the constitution of the individual themselves. Due to these reasons, the idea of a Lebensideal as a Gefahr, is almost impossible to determine. Critical Points/Personal Reflections Personal Reflection I will concentrate here on my impressions on the goal of the method employed by the dictionary article and how it succeeds in its task of clarifying certain concepts used by Nietzsche. I believe that the dictionary method of research is an effective way of concentrating the researchers’ attention on a specific concept. By concentrating on the meaning of one word the researcher is able to pick out a piece of the intricately woven puzzle that is Nietzsche’s philosophy and to examine it closely. Thus, they catch a glimpse of minute or barely audible aspects of Nietzsche’s thinking and are able to magnify them, whereas, otherwise, these aspects might be overlooked. After the magnification process, these aspects can be re-integrated into the framework of already understood elements of Nietzsche’s thought. This has, obviously, the advantage of providing new perspectives and fresh looks when it comes to interpreting what Nietzsche is saying in his books. This method provides an important depth with regards to the hermeneutical process and allows a more comprehensive and nuanced interpretation of Nietzsche’s text. By taking into account all of the different contexts in which the word is used, the methodology also assembles apparently disparate aspects of Nietzsche’s thought together under the rubric of a singular idea. This allows, thus, the researcher to see connections between different themes in Nietzsche’s work that they may not see otherwise. Another advantage of the dictionary method is that it allows for a new way of understanding how Nietzsche’s thinking changes over time. As noted in the article on Gefahr, after Morgenröte there is a pronounced shift in Nietzsche’s use of the word Gefahr. By cataloguing the use and context of different words the researcher is able to see not only general shifts in Nietzsche’s thinking, but also shifts that are reflected on a much more subtle level. The meanings of some words, for example, may change at 9 different points in Nietzsche’s life, and by taking note of the shifts that exist within certain concepts it is possible to see a much more detailed description of how Nietzsche’s thought progresses. Critical Point One personal reflection and subsequent critical point I have on the content of the article itself deals with the idea of ‘gefährlich leben.’ I am wondering to what extent it is beneficial to the individual to live in this manner. I am thinking this question especially as it concerns truth and the normalization effect of morality. Is it worth the risk to break free from its grip, is it foolhardy, is it too nihilistic, is all of this precisely Nietzsche’s point? To stare down into the infinite chasm and then to look up again at humanity, happily dancing on top of it, as if on nothing at all. This seems to be a thematic that occurs throughout Nietzsche’s work, especially in Über Wahrheit und Lüge im Aussermoralischen Sinne in which Nietzsche depicts humanity on the back of a tiger, dreaming of the truth in a full state of illusion. One could also point to Die Fröhliche Wissenschaft, aphorism 344, or Jenseits von Gut und Böse, aphorism 1 for a similar discussion of the topic. Living dangerously seems to indicate living a life in the absence of truth, whether it be societal or otherwise. It is a dangerous task to do so, for as with the image of the person on the tiger’s back, if the illusions of truth are shaken, the person runs the risk of being eaten by the tiger. So again, to what extent is living dangerously beneficial to the individual? As Nietzsche asks in aphorism 344 of FW, ‘But why not deceive? But why not allow oneself to be deceived?’ Is breaking the illusion of truth merely an accident, a victim of the will to truth that the individual follows faithfully, ignorant of its fatal consequences? And once the veil of naive innocence has been broken, is it then a necessity to live dangerously if the individual is to create any meaning and value within life? Once the foundation of all truth and morality has been removed due to thorough questioning, would it not be necessary for the individual to begin rebuilding from the base in order to continue living, assembling their structure based on the experiments they perform on themselves? Is not, in this sense, living dangerously a necessity? Having once broken the glass of truth, would it ever be possible to piece it back together in its original form, believing in its validity in good faith? It would seem 10 then that, on one level, truth and morality are beneficial to life, and not dangerous to it as is noted in the article. Perhaps here is a point of critic, as Giovanola might be differentiating between a positive and negative Gefahr a bit too easily. Each Gefahr, whether it be seen as ‘gefährlich leben’ or the Gefahr that morality poses to life, has its positive and negative aspects. Nevertheless, what is to be made of this seeming paradox? Does it even make sense to ask the question? Does the individual, who is driven by the will to truth, even have a choice in the matter of rejecting or accepting normative values, and thus whether or not they are to live dangerously? Conclusion The article presented by Giovanola is an interesting examination of how the word Gefahr is utilized by Nietzsche in his works. The result of reading the article is an interesting examination of the word’s use that provides for a new perspective on several aspects of Nietzsche’s philosophy, especially the famous phrase ‘gefährlich leben’. Nevertheless, there are issues concerning the structure of the article and its subsequent sub-categories that need to be addressed. The distinction between negative and positive Gefahr would also need to be reconsidered. Despite these facts, the article presents a good contribution to Nietzsche studies.