Week Eight Materials (Complete)

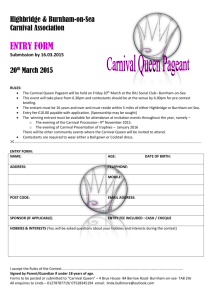

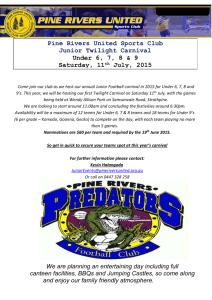

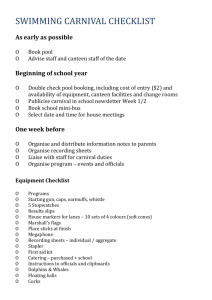

advertisement