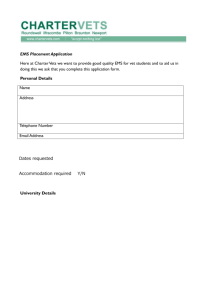

Environmental Management Systems (EMS)

advertisement