Top Ten Pennsylvania Employment Laws

advertisement

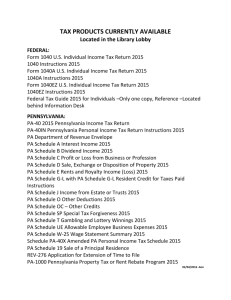

How to Defuse Pennsylvania’s 13 Most Explosive Employment Laws TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive summary 1. The Pennsylvania Unemployment Compensation Act 2. The Pennsylvania Workers’ Compensation Act 3. The Pennsylvania Human Relations Act 4. The Inspection of Employment Records Law 5. The Prevailing Wage Act 6. The Criminal Records History Act 7. The Pennsylvania Equal Pay Law 8. The Pennsylvania Wage Payment and Collection Act 9. The Pennsylvania Seasonal Farm Labor Act 10. The Pennsylvania Child Labor Act 11. 11. The Pennsylvania Medical Pay Act 12. The Industrial Homework Act 13. The Pennsylvania law on jury duty Executive Summary As a Pennsylvania employer, you’re forced to comply with more laws, rules and regulations than just about any employer in any other state. Pennsylvania is the land of government, big and small. In fact, there are an astonishing 5,334 governmental entities in Pennsylvania, including 67 counties, 56 cities, 964 boroughs, 1,548 townships, 501 school districts and 2,198 authorities. Each one, it seems, wants to control some aspect of how you run your business and treat your employees. And these come on top of all the federal laws and regulations you must follow! Running afoul of any Pennsylvania laws or regulations can cost you time and money. And some even impose personal liability on supervisors and managers who violate their mandates. That’s why it’s vital to know the ins and outs of these regulations. Examples: Say an angry employee demands to see her personnel file right now. You’d better know if the Personnel File Inspection Act says she has the right to see it. If you’re preparing the last check for an employee who quit but didn’t return his uniform, you’d better know what the Wage Payment and Collection Act says about docking his pay for the uniform’s cost. If you’re hiring seasonal help for a small Adams County farm, you’d better know how to comply with the Seasonal Farm Labor Act. These and other Pennsylvania laws give rights to employees far in excess of anything the federal government provides. But rest assured, you can comply with Pennsylvania’s employment laws without driving your company out of business (or driving yourself crazy). This special report, How to Defuse Pennsylvania’s 13 Most Explosive Employment Laws, will quickly bring you up to speed on the most important Pennsylvania employment laws. Meanwhile, your subscription to Pennsylvania Employment Law will keep you informed of the latest court rulings, laws, regulations and news that affect your role as an HR professional, supervisor, manager or business owner. This special report provides the basic employment-law framework for handling employees in Pennsylvania. It focuses on the 13 most important employment laws affecting Pennsylvania employers: 1. The Pennsylvania Unemployment Compensation Act 2. The Pennsylvania Workers’ Compensation Act 3. The Pennsylvania Human Relations Act 4. The Inspection of Employment Records Law 5. The Prevailing Wage Act 6. The Criminal Records History Act 7. The Pennsylvania Equal Pay Law 8. The Pennsylvania Wage Payment and Collection Act 9. The Pennsylvania Seasonal Farm Labor Act 10. The Pennsylvania Child Labor Act 11. The Pennsylvania Medical Pay Act 12. The Industrial Homework Act 13. The Pennsylvania law on jury duty Final tip: Heed local laws. In addition to these statewide issues, be aware that local governments also have the power to legislate within their borders. Some Pennsylvania cities and towns have greatly expanded discrimination laws, most often in the area of employees’ and applicants’ sexual orientation. Seven Pennsylvania cities (Philadelphia, Harrisburg, Pittsburgh, Lancaster, Allentown, York and New Hope) have enacted ordinances that prohibit job discrimination based on sexual orientation. Employers in these seven locations should contact their local governments for a copy of such ordinances. Typically, these cities have their own agencies or offices that handle complaints and enforce the law. Note: This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information on Pennsylvania employment law. It is sold with the understanding that the publisher and authors are not engaged in rendering legal, accounting or other professional advice. If legal advice or other expert assistance is needed, the services of a competent professional should be sought. Legal cases turn on the facts of each case, and an attorney well versed in the unique facts of your case and the law is best qualified to assist you. 1. The Pennsylvania Unemployment Compensation Act “Economic insecurity due to unemployment is a serious menace to the health, morals, and welfare of the people of the Commonwealth. Involuntary unemployment and its resulting burden of indigency falls with crushing force upon the unemployed worker, and ultimately upon the Commonwealth and its political subdivisions in the form of poor relief assistance.” — Policy statement accompanying passage of the Pennsylvania Unemployment Compensation Act. Pennsylvania’s unemployment compensation law, like that of many other states, provides temporary payments to employees who lose their jobs through no fault of their own. The law is administered through the Pennsylvania Department of Labor and provides unemployment pay to employees in some situations beyond the control of the employer. In effect, some Pennsylvania employers can actually be liable for unemployment payments even though their former employee voluntarily quit. Employers who don’t think a former employee is eligible for unemployment compensation must fill out the form they receive when the former employee files a claim. The matter will then be set for a hearing at the local unemployment compensation office. (You will receive a notice telling you when and where to appear.) The general rule is that former employees are eligible for unemployment compensation when they’re not responsible for their dismissal or that conditions beyond their control forced them to quit. In other words, unless the person was fired for cause, they’re probably eligible for the payments. So, be prepared to prove that the former employee was fired for a solid business reason, such as stealing, cheating, ignoring safety cautions or harassment or discrimination against co-workers. Employees’ reasons for earning benefit after quitting. Here are some common situations in which former employees may earn unemployment compensation even when they voluntarily quit: Health reasons. Employees may quit for health reasons and still collect unemployment, as long as they informed their employers before quitting to give the company a chance to arrange suitable work, within restrictions. Employers should look to their Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) accommodations records if the employee quit. If you had offered accommodations and the employee rejected them, he or she may not be eligible for unemployment compensation. Transportation. Some employees may be able to claim they had to quit because they couldn’t get to work. For example, if an employee has an accident and his car is totaled, he or she may be without transportation. As long as the employee looked for alternative transportation and none was available, he or she may be eligible for payments. To earn unemployment payments, such employees will, however, need to show that they’re looking for other suitable work that they can reach via public transportation or other means. Trailing spouse. In this day of dual-career families, a husband or wife may need to quit a job when the spouse accepts a job in another city. Sometimes the “trailing spouse” is eligible for unemployment compensation if he or she can show that the relocation was beyond their control (i.e., a company mandated the transfer) and the relocation created economic circumstances that could not be overcome. Leaving for personal reasons. If employees quit because of discrimination, harassment or the like, they may be eligible for unemployment. They’d have to show that they had no reasonable alternative. This claim is a red flag indicating that a discrimination claim is probably next. Be sure to consult an attorney right away. Job not what was anticipated. If employees leave a job because they felt mislead about the nature of the job, they may be eligible. For example, if a salesperson who was told he’d earn $50,000 per year in commissions ends up making considerably less, he may quit and earn unemployment, especially if his job-related expenses exceed his income. Employers’ reasons to deny unemployment. The following list includes common reasons an employee may be denied unemployment compensation benefits. The reasons fall into two broad categories: willful misconduct on the job and post-discharge conduct: Absenteeism and tardiness. To claim this as the reason to deny payments, employers must show they warned the employee before discharge. Generally, if the employee had a good reason for missing work, he is still eligible for unemployment. Good reasons include being sick or having a sick child. That is another situation in which clear workplace rules on absenteeism will be helpful. For example, if you can show that an employee didn’t follow your reasonable call-in procedures, he or she may be ineligible even though her underlying reason for being absent was legitimate. Rule violation. Deliberately breaking rules is another example of misconduct justifying denial of benefits. Be prepared to show that the employee knew about the rule and ignored it or refused to follow it. Disruptive influence. If you can show that an employee’s disruptive behavior is adverse to your interests as an employer, you can deny the employee benefits. Examples include harassing behavior, name-calling and the like. Damage to equipment or property. Negligent or purposeful damage to equipment makes the employee ineligible for benefits. Unsatisfactory work performance. Doing a poor job makes an employee ineligible for unemployment compensation, but only if he or she is not performing up to standards. This is one of the hardest areas to prove from the employer’s side. You must show that the employee is both capable of doing the work and is underperforming. If he or she is simply not qualified or unable to learn the job, then he or she is eligible for benefits. Able and available for work. Employees must be both able and available for work. For example, a former employee who refuses to look for work will not get benefits. Imprisonment. Those who are in prison are not eligible for unemployment. SUBHED = Who can represent you in unemployment hearings? Until recently, employers could represent themselves in unemployment compensation matters. It wasn’t an issue. That means, employees (such as an HR manager) could appear before the unemployment compensation board and make the case as to why a former employee shouldn’t be eligible for payments. That was a fairly common practice, as hiring an attorney was often seen as too expensive when so little was at stake. But in early 2005, a Pennsylvania appeals court ruled that most employers had to hire an attorney to represent their organizations in unemployment compensation hearings. In response to that decision, Pennsylvania lawmakers amended the Unemployment Compensation Law in June 2005. That new section said that, "any party in any proceeding … may be represented by an attorney or other representative." Once again, it appeared employers are able to use non-lawyers to advocate at hearings and file UC appeals and briefs. Unfortunately, the issue is still up in the air at the time this special report went to press. While the new law appears to allow non-attorneys to represent employers, the original case was appealed to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, which has not yet ruled. The state supreme court will decide whether the use of a non-attorney amounts to the unlawful practice of law in Pennsylvania. The Pennsylvania Bar Association has come out against the new law. Although at present, the Pennsylvania Department of Labor advises employers they are free to represent themselves without an attorney, you should ask your own attorney whether that is still the law. SUBHED = Beware: UC hearing evidence can trigger lawsuit later Keep in mind that unemployment compensation hearing officers (“referees”) often take evidence under oath. What you say about your company’s actions can come back to haunt you later, especially if the former employee is using the relatively low-stakes unemployment hearing to fish for information for a later lawsuit against your organization. What you say about why an employee was fired in this UC hearing may bind you later in a high-stakes lawsuit. For that reason, always run your expected testimony and documentary evidence by the company attorney before you represent the company. You don’t want what you say now to be used against you later. Sometimes, it may be best to have an attorney handle the case. Other times, if you and your attorney think the former employee will file a state or federal discrimination lawsuit, it may be better to forgo a hearing altogether to avoid showing your cards too early. Not contesting an unemployment claim will not prevent you from showing the employee was fired for a legitimate reason later. 2. The Pennsylvania Workers’ Compensation Act The Workers’ Compensation Act covers all employers in Pennsylvania and provides wage replacement for employees hurt on the job. The law provides payments to employees regardless of fault. That is, to earn benefits, injured employees don’t have to prove that their employers were negligent; they only need only prove that the injury occurred at work. Sounds simple, right? It’s not. To give you an idea of the complexity of the Pennsylvania Workers’ Compensation Act, consider that the Department of Labor’s guide to the law totals 361 pages itself. Yet, you can’t afford not to master the basics because workers’ comp claims are some of the most common employment claims your organization faces. Together with unemployment claims, injury claims typically make up the bulk of employment related lawsuits for most employers. Although the law is a no-fault law, a few exceptions do exist. For example, employees who die or are injured under the following circumstances don’t earn workers’ comp benefits: When the injury or death is intentionally self-inflicted. When the injury or death is caused by the employee’s violation of law, including, but not limited to, the illegal use of drugs. During hostile attacks on the United States, injury or death of employees results solely from military activities of the armed forces of the United States or from military activities or enemy sabotage of a foreign power. When death is caused by intoxication, no compensation shall be paid if the injury or death would not have occurred but for the employee’s intoxication. Presumably, employees killed in a terror attack such as those of September 11, 2001, would not receive workers’ comp benefits, nor would an employee who shot and killed herself after shooting co-workers. The co-workers killed or injured would, of course, be eligible for benefits. Some types of employees aren’t covered by the law. These include: Federal workers, longshoremen and railroad workers. Agricultural workers who make less then $1,200 per year and work no more than 30 days per year. Sole proprietors or general partners. Some executive officers. Licensed real estate salespersons or real estate brokers. Licensed insurance agents who are paid on a commission basis and are independent contractors. SUBHED = Maintaining workers’ comp coverage All Pennsylvania employers must obtain and keep workers’ compensation insurance on employees or arrange with the Pennsylvania Workers’ Compensation Bureau to self-insure. As long as your company employs at least one employee, you must buy coverage. Premiums depend on the type of work the employee does. Costs rise according to the risk associated with the job and on your claims history. Therefore, it is very important to do all you can to reduce or eliminate injuries. If you don’t maintain workers’ comp insurance, you could face criminal penalties. The law says those responsible to act on the behalf of the company to obtain or maintain insurance are criminally responsible if the premium isn’t paid. The company can also face charges. In addition, if an employee is hurt and the employer doesn’t hold insurance, the employee can elect to receive what he or she would have received if there were a policy in place or can sue the company for negligence. If the employee proves the company’s negligence contributed to the injury, there is no limit on the amount he may receive. The law allows a separate criminal charge for each day that insurance isn’t in effect. If your lack of coverage was unintentional, the crime is a misdemeanor and the penalty is up to $2,500 per day and one year in prison per day. If the lack of coverage is intentional, the offense is a felony and carries a maximum $7,500 perday fine and a maximum seven-year per day prison term. SUBHED = Tips for reducing workers’ compensation costs You can earn a 5 percent discount on your insurance premium if you set up a certified workplace safety program through the Bureau of Workers’ Compensation. Provide available jobs to injured workers if their injuries allow them to perform those jobs. Designate certain doctors and treatment facilities for injured workers to use during the first 90 days after injuries. If employees go elsewhere, you aren’t responsible for the bills for the first 90 days. Report suspected fraud to your insurance carriers. SUBHED = How to handle a claim All Pennsylvania employers are required to post a notice about workers’ compensation coverage. The notice must be placed at the primary place of business and at each work location, and it must include the name, address and telephone number of the insurer and other party to whom workers can report injuries and claims. Employees have 120 days to report their injuries to their employers. Also, if employees wait longer than 21 days to report the injury, they don’t get benefits until they actually report the incident. For example, if an employee slips in the parking lot on Jan. 1 while walking from one plant to another but files an incident report on Feb. 1, he won’t earn benefits for the first month. When you receive a workers’ comp a claim, be sure to immediately report the matter to the insurance carrier. You will then coordinate everything through the carrier. Usually, the carrier determines if the case is valid. If there is a question about the injury, the carrier may ask for a hearing. Then, you’ll be asked to provide supporting documents. Workers’ comp cases are not usually resolved in one hearing. Typically, testimony takes place over a number of months and payments continue until a workers’ compensation judge rules the case is valid or concludes the employee is not injured or has healed fully and is ready to return to work. SUBHED = The ADA, FMLA and workers’ comp Because employees injured at work may also be disabled under the ADA and have a serious medical condition that qualifies them for FMLA leave, be sure to coordinate any unpaid leave and reasonable accommodations—such as light-duty work or intermittent leave—with the HR professional handling ADA and FMLA claims and the insurance carrier. It’s important that these claims be coordinated. Nothing will sink a case faster than evidence that an employer acquiesced to a workers’ compensation claim and refused to allow an FMLA claim for the same condition. 3. The Pennsylvania Human Relations Act “It is hereby declared to be the public policy of this Commonwealth to foster the employment of all individuals in accordance with their fullest capacities regardless of their race, color, religious creed, ancestry, age, sex, national origin, disability, use of guide or support animals because of the blindness, deafness or physical disability of the user or because the user is a handler or trainer of support or guide animals, and to safeguard their rights to obtain and hold employment without such discrimination, to assure equal opportunities to all individuals and to safeguard their rights to public accommodation.” – from The Pennsylvania Human Relations Act Employers of four or more peole must comply with the Pennsylvania Human Relations Act (PHRA). The law is administered by the Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission (PHRC), which also is the agency that receives the initial federal discrimination charges made under Title VII of the federal Civil Rights Act. In effect, the agency gets first crack at most discrimination cases brought by employees in Pennsylvania. In addition to the types of employment discrimination covered by Title VII (race, color, religion, sex, or national origin), the Pennsylvania law makes it illegal to discriminate against people who have a GED instead of a high school diploma. Employees have 180 days from the date of alleged discrimination to file a complaint with the PHRC. People or organizations can file complaints. For example, the American Association of Retired Persons can file an age discrimination complaint with the PHRC as long as at least one named member of the organization has been affected by the alleged age discrimination. Once the PHRC receives a written complaint, the agency must investigate unless the case is clearly frivolous. Employers will receive a written copy of the complaint and will be asked to respond in writing. As soon as you obtain the copy, notify your insurance carrier and attorneys, who can guide the response. Typically, the PHRC will schedule an informal conference to discuss the case and to gather evidence. Be sure to respond. Most cases are dismissed or referred to the EEOC for further action. Some cases are resolved informally at the PHRC. If the case is deemed without merit, the agency will send a letter to the employee letting him or her know the result and explaining her options to sue. PHRA may apply to smallest employers. Although very small employers (those with 3 or fewer employees) aren’t technically covered by the PHRA, a recent ruling for the first time cited a “public policy” exception that would allow claims to proceed against even smaller-sized employers. That case involved an office manager who quit her job and filed a sexual harassment claim under the PHRA. A lower court tossed out the claim, saying her employer didn’t employ the minimum number of four employees to be considered an “employer” under the law. But the state superior court let her case go to trial, creating an exception when a clear public policy (preventing harassment) would be subverted by not letting the case proceed. The court said the PHRA’s fouremployee threshold should not be construed “as a tacit endorsement of sexual discrimination against their employees.” (Weaver v. Harpster & Shipman Financial, Pa. Superior Ct., No. 394) The bottom line: Once you employ even one employee, you must familiarize yourself with the discrimination laws. 4. The Inspection of Employment Records Law Employers must allow employees (or their designated agents) to inspect their personnel files upon reasonable request. The law only applies to people who are actually employees. That is, it does not apply to applicants who want to look at their application files or to ex-employees. It does apply to any person currently employed or who has been laid off with the right to recall or who is on a leave of absence. The law defines an employment file as any record maintained by the employer, including: The application. Wage and salary information. Commendations, warnings or discipline. Authorizations for deductions or withholding. Fringe benefit information. Leave records. Employment history with the employer. Job titles. Attendance records and performance evaluations. You don’t need to let employees see records concerning criminal investigations, letters of reference, documents being prepared for lawsuits or medical records. You also aren’t required to let employees or their agents remove or copy the files, but must allow them to take notes. Employers may limit the inspections to once per year for each employee and each agent. 5. The Prevailing Wage Act Organizations that perform work on public works projects in Pennsylvania must pay the prevailing wage for various semi-skilled positions, as determined by the Prevailing Wage Board. Prevailing wages are determined for each job and locality. Employers are required to maintain detailed pay records showing exactly what wage was paid to each worker, the specific work performed and locality where the work was performed. Employers who willfully violate the law may face penalties and they risk losing their ability to bid on other state contracts. Unintentional violations are corrected by paying the worker the disputed funds. 6. The Criminal Records History Act Employers can refuse to hire job applicants based on the person’s criminal history only if the criminal record directly relates to the “applicant’s suitability” to the job. Employers can’t use “summary offenses” as a reason to not hire an applicant. (Note: All crimes in Pennsylvania are rated by seriousness. Summary offenses are minor offenses, such as speeding tickets, jaywalking, littering and disorderly conduct. Misdemeanor offenses are more serious, including charges such as simple assault or shoplifting goods worth more than $150. Felonies are serious crimes.) The Pennsylvania law requires that employers notify applicants if the decision not to hire them was based in whole or in part on their criminal record. The burden is on employers to show that an applicant’s criminal record makes him or her unsuitable for the job. In some cases it may be obvious. For example, an applicant with a recent history of theft probably isn’t a good candidate for a bank teller position. But that same conviction may not be relevant to a position that doesn’t involve money, such as a custodial position. Certain jobs, such as those in schools and day care centers, require that employers obtain a criminal records check from the Pennsylvania State Police before hiring the applicant. Applicants with a history of violent crimes are disqualified from these types of jobs. 7. The Pennsylvania Equal Pay Law The Pennsylvania Equal Pay Law parallels the federal Equal Pay Act in many respects. It says that employers can’t discriminate in pay rates because of an employee’s gender. The law covers every Pennsylvania employer, regardless of size. It differs in one important aspect from the federal law: It makes not paying the same rate of pay because of the employee’s gender a criminal offense. The test of whether two employees are paid equally depends on whether the positions require equal skill, effort, and responsibility and are performed under similar working conditions. Differences can be legally justified if the employer can show they are the result of any of these factors: A seniority system. A merit system. A system that measures earnings by quantity or quality of production. A differential based on any other factor than sex. The law also makes it illegal to reduce the wages paid to one gender of employees in order to equalize the pay structure. Employers found guilty of violating the law must pay twice the amount of lost pay owed to the wronged employee or employees. The law specifically allows classaction lawsuits, and it prohibits retaliation against employees who bring charges under the law. Employees can bring retaliation charges against employers or individual supervisors. Penalties for retaliation range from $50 to $200 per violation. Each day of retaliation is considered a separate offense. Should the guilty employer or supervisor refuse to pay the fine, the law authorizes a jail sentence of 30 to 60 days per offense. Similarly, failure to keep or produce when asked pertinent payroll records can bring the same fines, or jail time. 8. The Pennsylvania Wage Payment and Collection Act The Wage Payment and Collection Act requires employers to pay wages on regular paydays or face fines or imprisonment. You must pay regular wages within 15 days of the end of the pay period. Employers must notify employees of paydays and pay period dates at the time of hire. Essentially, this is the legal justification for “holding” one pay period’s wages back. Employees can file lawsuits under this law individually or in a class. Upon receiving such a complaint, the Department of Labor may demand that the targeted employer post a bond for the amount in dispute. Liquidated damages of 25 percent of outstanding money or $500 (whichever is greater) is available to employees, should they make their case. What must you do if you terminate employees or they quit before the end of a regular pay period? If such ex-employees demand their wages immediately, must you cut them a check? The answer is “no.” You don’t need to deliver the final paycheck until the next regularly scheduled payday even if the employee only worked part of the time. For example, if you have a 14-day pay period, and the employee quits on the first day, you would have a total of 28 days to pay him or her (13 days plus 15 days). The law also makes it illegal to enter into a contract with an employee that would make the waiting period longer. You can, however, agree to pay earnings earlier if you want. There is nothing, for example, to prohibit you from paying employees on the last day of the pay period or making the pay period shorter. Employers who violate the Act are subject to fines of $300 or up to 90 days in jail. 9. The Pennsylvania Seasonal Farm Labor Act Pennsylvania has a vibrant farm sector and family farms are still a big part of the agricultural picture. These farms often require seasonal help. For example, the apple orchards of Adams County rely heavily on migrant workers during the apple harvest. To regulate the working conditions of migrant farm workers, the legislature passed the Pennsylvania Seasonal Farm Labor Act. This act establishes minimum wages and labor hours for seasonal farm workers. It says that employers must pay seasonal farm workers the established farm labor minimum wage for each hour worked. Farm laborers aren’t entitled to overtime. Farm workers may be paid on a piece-rate basis. Minors must be paid the same as adults. Children who are members of the employer’s immediate family can work even if they are under 14 years of age. Workers ages 14 to 17 can work on a farm during non-school hours. Farm owners may establish farm labor camps. The camps must meet specific standards and are subject to periodic inspection by the state Department of Labor. Various penalties apply for farm labor camps that are found to be in violation of the law. Farm labor contractors must obtain a license from the Department of Labor, and are restricted in their activities with farm laborers. 10. The Pennsylvania Child Labor Act The Pennsylvania Child Labor Act restricts employers’ ability to hire minors. Children 12 to 14 can work as golf caddies (within certain restrictions) and children ages 14 to 16 can work during non-school hours. People under age 18 may not work more than six consecutive days. Certain occupations set specific laws governing child employment, including motion picture filming, the selling of newspapers and working as a bootblack. Employers must provide a child employee’s school district a copy of his or her work permit within five days of the start of employment. Employers who violate the law are subject to fines. Tip: Always check the child labor provisions of the federal Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), too. You can find them at www.dol.gov/dol/topic/youthlabor. For more details on child-labor laws in Pennsylvania and other states, go to www.dol.gov/esa/programs/whd/state/nonfarm.htm. 11. The Pennsylvania Medical Pay Act The Pennsylvania Medical Pay Act requires employers to bear the costs of employee medical examinations when those exams are a condition of employment. The law covers all Pennsylvania employers and prohibits forcing a job applicant to pay for any medical testing that is a condition of employment. Similarly, employers must bear any cost necessary to produce medical records. Employers found guilty of violating the law face a fine of between $10 and $100 for each offense. Remember that the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) has special provisions for post-offer and pre-employment medical examinations and for necessary testing. Be sure to coordinate those rules with the Pennsylvania law that requires you to foot the bill. For example, if you require an employee get a doctor’s certification that an applicant has had necessary immunizations, be sure to pay the charge for reproducing the records. 12. The Industrial Homework Act This law regulates—and in some cases prohibits—industrial homework, which the law defines as, “any manufacture in a home of articles, or materials for an employer, representative contractor or contractor.” In other words, no in-home sweatshops are allowed in Pennsylvania. The act specifically prohibits the home-based manufacture of: Articles of food or drink. Articles for use in connection with the serving of food or drink. Toys and dolls. Tobacco. Drugs and poisons. Bandages and other sanitary goods. Explosives, fireworks and articles of like character. The tearing or sewing of rags. (Some exceptions apply.) Hazardous materials. To accommodate disabled employees, permits are available for the manufacture of some items as long as the employee is at least 16 years old and isn’t suffering from an infectious or contagious diseases. To obtain a permit, employers must produce medical certification of the disabled worker’s condition to the Secretary of Labor. Medical certification of the worker’s condition is obtained at employer expense. Special provisions apply to people who manufacture shoes in their home. Shoemanufacturing home workers don’t need to be disabled to obtain a certificate. Any item manufactured in a home must be conspicuously labeled as such. Violations of the law carry a $1,000 fine or 60 days in jail. Selling or transporting unlabeled home-manufactured goods carries a $500 fine or 30 days in jail. A second violation within five years can bring a $5,000 fine and or a 60-90 day jail sentence. Tip: Be sure to check whether a work-at-home accommodation for a disabled employee conflicts with the law. This law is something of an anachronism, although it does appear to allow a work-at-home system for sewing garments and the like. 13. The Pennsylvania law on jury duty “An employer shall not deprive an employee of his employment, seniority position or benefits, or threaten or otherwise coerce him with respect thereto, because the employee receives a summons, responds thereto, serves as a juror or attends court for prospective jury service.” — 42 Pa. C.S.§4563 The right to a jury trial is guaranteed in the U.S. Constitution and in all state constitutions. If people called to serve on juries could be punished for serving, it wouldn’t be long before courts wouldn’t be able to muster enough people to create jury panels. Because Pennsylvania takes jury duty seriously, the legislature passed a law prohibiting most employers for retaliating against or punishing employees who become jurors. Ordinarily, most employers won’t be seriously inconvenienced by an employee’s jury duty. Most jurors serve for just a few days or a week. In some cases, jurors hearing complicated cases may be sequestered. Only rarely do jurors serve longer than two weeks. However, someone who is picked to serve on a statewide investigative grand jury could serve for 18 to 24 months, one week per month. Pennsylvania law doesn’t require employers to compensate employees for jury duty. However the law is very clear that employers can’t interfere with employees’ fulfillment of their civic duty. Employers aren’t allowed to “deprive an employee of his employment, seniority position or benefits, or threaten or otherwise coerce” an employee because he is summoned for jury duty or serves as a juror. Employers who violate this statute are guilty of a summary criminal offense. Employees must file suit to recover lost wages and benefits. Losing employers will also be responsible for the employee’s attorney fees. As the Pennsylvania law is written, employers in the retail industries are exempt if they employ fewer than 15 people. Manufacturers are exempt if they employ fewer than 40 people. However, a recent Pennsylvania case ruled the exemption was illegal in a case where the employer had fewer than 15 employees. The reason? The court thought that firing an employee called to jury duty was wrong because the effect is to limit the available jury pool. Since Pennsylvanians are entitled to a “representative” jury pool by another law, the jury-duty exemption was unconstitutional and the small employer could still be held liable for firing the employee. As a practical matter, most judges will excuse jurors who work for small employers if they ask. Advice: Develop a simple jury duty policy that shows you understand that jury duty is an important civic duty. Although you are not required to pay employees who take time off to serve, you may want to consider allowing jurors to take vacation or personal days. You may also want to consider paying employees for a week of jury duty, minus the amount the court pays jurors. Pennsylvania Employment Law Resources STATE RESOURCES Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission www.phrc.state.pa.us Harrisburg regional PHRC office Riverfront Office Center 1101-1125 S. Front St., 5th Floor Harrisburg, Pa. 17104-2515 (717) 787-9784 Philadelphia regional PHRC office 711 State Office Building, 1400 Spring Garden St. Philadelphia, Pa. 19130 (215) 560-2496 Pittsburgh regional PHRC office 11th Floor State Office Building 300 Liberty Ave., Pittsburgh, Pa. 15222 (412) 565-5395 Pennsylvania Department of Labor & Industry www.dli.state.pa.us Bureau of Labor Law Compliance regional offices: PHILADELPHIA 1400 Spring Garden St., Room 1103 Philadelphia, Pa. 19130-4064 Phone: (215) 560-1858 SCRANTON 100 Lackawanna Ave., Room 201-B Scranton, Pa. 18503 Phone: (570) 963-4577 Toll Free: (877) 214-3962 HARRISBURG 1301 L & I Building 7th & Forster Streets Harrisburg, Pa. 17120 Phone: (717) 787-2026 PITTSBURGH. 300 Liberty Ave., Room 1201 Pittsburgh, Pa. 15222 Phone: (412) 565-5300 Toll Free: (877) 504-8354 Bureau of Workers’ Compensation 1171 South Cameron St. Harrisburg, Pa. 17104-2501 (717) 783-5421 Web site: www.dli.state.pa.us (click on “Workers’ Comp” under Quick Links tab) E-mail: ra-li-bwc-helpline@state.pa.us Employer information services: (717) 772-3702 Compliance section: (717) 787-3567 LOCAL AGENCIES Harrisburg Human Relations Commission City of Harrisburg McCormick Public Services Center 123 Walnut St., Suite 235 Harrisburg, Pa 17101 Phone: (717) 255-3038 Philadelphia Commission on Human Relations www.phila.gov/humanrelations 34 S. 11th St., 6th Floor Philadelphia, Pa. 19107 Phone: (215) 686-4670 North Philadelphia Field Office 601 W. Lehigh Ave. Philadelphia, Pa. 19133 Phone: (215) 685-9761 Pittsburgh Commission on Human Relations 908 City-County Building 414 Grant St. Pittsburgh, Pa. 15219 Phone: (412) 255-2600