Century Summaries and Video Segments Word Document

advertisement

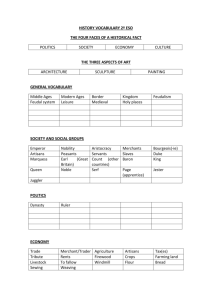

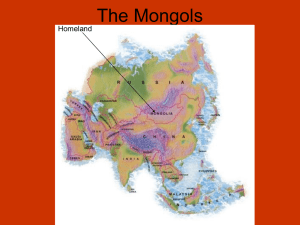

Tape Episodes 11th Century – Century of the Sword As the second millennium began on the Eurasian continent, vibrant civilizations were concentrated in China, India, and the Islamic World. The sword symbolizes the 11th century, not because the 11th was any more violent than other centuries of the millennium, but because it was riven by fundamental divisions within and between many cultures. Among these divisions were conflicts between China and her neighbors, conflicts connected with the expansion of Islam, and conflicts within the Christian world. The sword also represents cleavage, separation, and insularity. Such was the case in Japan, where ties with outside cultures were diminishing or virtually non-existent. Yet despite violence and separation, the 11th century was marked by vibrancy, creativity, and a great deal of cultural transfer, especially in the Islamic World and in East Asia. As the world began a new millennium in the 11th century, only within Christendom did the word "Millennium" have much significance. Only there was chronology counted from Christ's birth. The rest of the world marked time in other ways, a fact which symbolizes the world's cultural and regional disconnectedness during this period: although cultures met, touched, interacted, and exchanged, for the most part they remained separated and separate. Looking at Eurasia, there were in the 11th century four great cultural constellations-China, the Muslim World, India, and Christendom. China considered herself the center of the universe, dominant in the world of technology, and home to a vibrant internal market and culture. When outsiders attacked, China often survived by absorbing her enemies rather than beating them on the battlefield. Yet, China was set off from the rest of the world by barriers, some geographical like the Takla Makan Desert. Meanwhile, Islam expanded, absorbed and preserved Greco-Roman science and arts, and then produced a brilliant synthesis of Islamic and neighboring cultures. Such a cultural fusion is richly reflected in the Spanish city of Cordoba. India, to the east, was also affected by Islamic travellers and conquerors who occupied northern India in 1000 AD. Eleventh century India, a relic of a former great civilization that had produced two world religious traditions was, at one time, at the forefront of the sciences. Nowhere, except perhaps Ireland, in the 11th century is isolation more evident than in Japan. After centuries of borrowing from China, Japan in the 11th century solidified her imperial tradition in splendid isolation. Separation occurred also within Christendom. In 1054, a split that had been brewing for centuries, finally forever divided Christendom between East and West, Orthodox and Catholic. The East became more vulnerable to Islam while the West entered the second millennium unencumbered, ready to begin the creation of a dynamic new society that formulated institutions and ways of thought that were destined to change the course of world history. Segments – 11th Century CHINA - Summary In China, barbarians from the north swept down to seize some of China's wealth. In the course of this invasion, the bustling, cosmopolitan city at the heart of China-Kaifeng-was sacked. Confucian scholars remained confident, however, that China's culture would endure. As it turned out, they were more or less right: China was a center of world innovation and would not be restrained for long. Chinese civilization had produced the print block, paper money, the compass, the seismograph, an accurate water clock, acupuncture, medical sciences, and gunpowder. The invaders, rather than crushing these achievements, were seduced by such sophistication and adopted Chinese ways. JAPAN - Summary Treacherous seas separated the Japanese from much of the world. At the heart of the Japanese islands was a court where manners had became increasingly refined. Female courtiers were expected to be skilled in many things. Writing talent in particular was highly valued. Sei Shonagon was one such courtier skilled in letters. Her portrait of court life has been preserved, as fresh today as it would have been in the 11th century. Perhaps because her world was confined to the walls of the palace complex, she observed her surroundings in their minutest details: the raindrops on a spider's web, the wind created by a mosquito's wings, the play of light on water as it is poured into a vessel. She also recorded awkward and embarrassing moments, such as when a man lay awake at night talking to his companion, only to have the companion go on sleeping. Sei Shonagon's nights were full of intrigue as various lovers tiptoed around the palace complex to visit her and the other ladies of the court. Although this court culture was only a small part of Japanese reality, it typifies this introspective and insular society, which would show no signs of initiative for several centuries to come. INDIA - Summary For centuries, India had provided much of the rest of Asia with sacred scriptures and scientific texts. In the 11th century, the Muslim scholar Alberuni visited India to learn the secrets of Indian wisdom. He travelled around the subcontinent for 15 years, visiting sacred temples and studying Sanskrit. He marvelled at the industry of the various Indian peoples he encountered but was puzzled by the behaviour of India's religious leaders. The priests did not take shelter, nor did they wear clothes. The great learning of the previous millennium was no longer in much evidence; instead he found a civilization that had become self-absorbed. SPAIN - Summary The Islamic World was a young and vigorous civilization in the 11th century. Over the preceding four hundred years, the warriors of Islam had conquered vast tracts of territory. Once converted by traders, the nomadic tribes of the Sahara and central Asia proved to be even more zealous evangelists than their mentors. During this century, Turks displaced Arab rulers in Asia and Egypt, and real military expansion occurred on many fronts, including sub-Sahara Africa, North Africa, Afghanistan and Spain. Muslim traders also extended and consolidated Islamic influence. They operated across great distances, connecting the African continent to the Middle East, Christendom and Asia. At the heart of the western Islamic world lay Cordoba. Like many Islamic cities, it boasted hundreds of gardens, shops and baths. It was a mirror of paradise. JERUSALEM - Summary Christendom was also on the fringes of the greater civilizations, and in the 11th century was split irrevocably into two separate geographic and ideological factions. The West held the wealthy Eastern Church in contempt, while the more urbane Eastern Church considered the Christians of the west to be barbarians of little faith. In 1054, years of political wrangling reached a climax. The Pope in Rome issued a document formally excommunicating the Eastern Church. It was a rift that would create divisions within Europe for centuries after. At the time, it appeared that prospects for this part of the world in the future were dim. However, the drive to clear the forests and spread the Christian faith into the corners of the continent proved to be a powerful force of revival later in the millennium. Rapid expansion would begin on all frontiers-the seeds of Western dynamism were already in hand. 12th Century – Century of the Axe In CNN's MILLENNIUM, the Century of the Axe was an age of ambitious building, as world populations beeomed and cities thrived. Filmmakers chose the axe as a fitting symbol for the twelfth century because people used it to clear the land for food and housing, thereby transforming and remodeling the world. Some builders created monuments to their gods. Other individuals chose not to build but insead worshipped the land that gave them sustenance. According to MILLENNIUM's filmmakers, the twelfth century was most conspicuously the century of the axe in Western Europe, but other parts of the globe displayed innovative building and creativity. In Western Europe, life and building rebounded after centuries of stagnation under feudalism. In France, ever more elaborate churches were constructed; in Italy, a frenzy of city-state building reflected growing competition between independent city-states over trade and wealth. In other quite distant parts of the world, building of other types took place. In Ethiopia, Christian temples were carved out of mountains and the Chaco Canyon in the Americas, the Ancient Pueblo people built complex, urban-like structures on canyon floors. And for the twelfth century hunter-andgatherer culture of the Aborigines in Australia, the axe is symbolic of artistic creativity and control over the environment. Segments – 12th Century AMERICA - Summary In North America, a civilization arose which transformed a semi-desert into a cultivated landscape. The Ancient Pueblo peoples of the Southwest imposed a new geometry on the landscape. At Pueblo Bonito in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, stand the ruins of what was once a complex of structures with more than 800 rooms. The rooms were stacked on top of one another in a huge semi-circle, a plan that the Pueblo people devised and kept to for 200 years. The timbers that supported the vast roofs of the dwellings were brought by hand from forests over 60 miles away. Around the buildings lay carefully cultivated fields with crops of maize and squash. To allow crops to grow in such an arid environment, the Pueblo people created an ingenious system of irrigating channels. Dug deep into the rocks and dirt of the surrounding mesa tops, these channels captured droplets of rain from passing storms or melting snow. The water then fed into fields where it was retained by built-up earth around each plant. This "waffle" irrigation system sustained a growing population for several hundred years. But after a series of persistent droughts towards the end of the twelfth century, even these levels of ingenuity could not help the settlement. It was eventually abandoned. FRANCE - Summary In northern France, forests were cleared at faster and faster rates. As the population grew, the pressure for land increased. Churches and houses were usually made of timber, but as the number of suitable trees dwindled the structures had to change. At St. Denis in Paris, Abbot Suger dreamed of rebuilding the old abbey. His inspiration was a mystical vision of heaven. He envisioned slender stone columns, huge windows, and a mighty roof that would draw the eye upward toward heaven. Skeptics told Abbot Suger he would never find trees large enough to stretch across such an expanse, but he persevered. He finally found twelve trees tall enough to span the roof and was able to build his dream cathedral. St. Denis, a mixture of stone and wood, was completed in Suger's lifetime. However, it would go through several renovations; as cathedrals continued to expand, more and more stone was used. The construction of St. Denis sparked the beginning of the new style of "Gothic" architecture. Over the next 150 years, cathedrals sprang up throughout Europe. ETHIOPIA - Summary While churches sought to rise to the sky in Europe, in Africa they were being carved out of the earth. In the highlands of Ethiopia during twelfth century, a man called Lalibela rose to power, was crowned King, and went on to establish a Christian empire spanning the highlands and stretching to the sea. His ambition was to build a religious state and a spiritual center to rival Jerusalem. He claimed to have been shown - in a vision - the most holy of churches in Heaven. He ordered tools be made to carve temples out of the rock like those he had seen. Craftsmen toiled in the stony mountains for over twenty-four years to create these unique rock churches. Some of Lalibela's motivation to build these unusual structures stemmed from a desire to claim legitimacy. He belonged to a dynasty that had seized the throne and the churches helped him gain acceptance. His efforts paid off: today he is revered as a saint and his shrine attracts a continuous flow of pilgrims. While all religions at one time or another have constructed shrines and physical symbols to serve an ideological purpose, striking awe into to the layman and establishing the clergy's direct connection to the power of God, Lalibela clearly lacked legitimacy and used these temples to insure his leadership. ITALY - Summary In the twelfth century, cities grew worldwide. In Italy, a booming economy and population explosion meant increased demand for goods and space. People gathered in cities to trade and settled in increasingly cramped spaces. Despite feuding between factions within cities, a spirit of citizenship emerged. In many towns and cities republics were established, consuls were elected, and citizens assigned rights. Residents were proud of their cities and strove to make them more glorious than their neighbors'. In Sienna, in Tuscany, an event known as the Palio originated and became a tradition. This bi-annual bareback horse race round the central piazza celebrated the city spirit while also serving as a peaceful outlet for the rivalries among different quarters of the town. AUSTRALIA - Summary In Australia in the twelfth century, the Aboriginal culture flourished. Though they did not build, the Aboriginal' creativity centered around art: they endowed every landmark with sacred significance and celebrated it with rituals. The journeys of ancestors were retraced again and again over centuries; a physical pilgrimage through artistic celebrations. The Aborigines' universal language was art. For forty thousands of years they created paintings in galleries of rock intended to be overlaid by other artists over time. Aborigines left their mark on the land in other subtle ways. Fire was a core technology, and they used it to modify the wilderness by burning sections and clearing it for grazing animals. Fire sticks were used to chase animals out of their burrows. They did not cultivate crops, but instead gathered foodstuffs offered up by the land. Aboriginal culture developed a detailed and crucial knowledge of what was edible and exactly where it was to be found. Aboriginal society survived in isolation until Europeans began to colonize in the 18th century. 13th Century – Century of the Stirrup Early in the thirteenth century, the Mongols became a formidable power in Asia. Their new, bureaucratic way of organizing their army - by tens, hundreds, thousands - broke up the older Klan groupings. While horses and stirrups had been familiar for centuries, the Mongol's skilled horsemanship made them powerful and profoundly changed the course of history. Thus, the filmmakers of MILLENNIUM chose the stirrup as the symbol of for the thirteenth century. The symbol of the stirrup captures the essence of the rise of the Mongols and their remarkable thirteenth-century advance across Eurasia. It also evokes the importance of travel along the reopened transcontinental Silk Road which transported both goods and knowledge. Few areas of Eurasia were untouched by the Mongols, but their advances and conquests meant different things to different peoples. For western Europe, the Mongols were the means of transmission of important knowledge and goods that a century later would enable Europeans to set sail across oceans. For China, Mongols established their rule but not cultural subjugation. The Mamluks in Egypt gained fame as the first to successfully defeat the Mongols, thereby protecting Mamluk Islamic culture. And for the Mongols themselves, their horse-riding prowess meant the beginning of the end of nomadic existence and control of the Eurasian steppe. Segments – 13th Century MONGOLIA - Summary In the Century of the Stirrup, the Eurasian landmass was transformed by the emergence of a new force in history: the Mongols. Genghis Khan founded an empire that would eventually stretch from China to the Middle East, blocked only by the Mamluks in Egypt. While regular caravan travel between China and Mongolia began in 101 B.C.E., after the creation of the Mongolian Empire the trails connecting the East to the West became safe to travel. As the "Silk Road" flourished, Chinese knowledge flowed westward, stimulating new approaches to science and religion. Genghis Khan grew up among the Mongols, then rose quickly to prominence, proving himself to be an extraordinary leader. He quickly dominated the tribes of Central Asia and then went on to conquer parts of Northern China and the Islamic world. He used terror tactics to scare people into submission, sparing only skilled artisans if a town failed to surrender. Once a land was conquered, however, the Mongols were very tolerant rulers, allowing other faiths and traditions to continue. The method of Genghis Kahn's leadership was so strong that the army and empire he founded continued to grow after his death. CENTRAL ASIA - Summary The Mongols enforced law and order across Central Asia, policing a network of routes connecting East and West. They built post stations throughout the empire from which messages were carried at high speed across vast distances. The hostile impressions some foreign visitors formed changed as they spent more time with the Mongols. William of Rubruck found that in Karakorum, the main Mongol city, there were "very fine craftsmen in every art, and physicians [who knew] a great deal about the power of herbs and diagnose[d] very cleverly from the pulse." The religious tolerance Rubruck discovered would have been unimaginable in Europe at that time. CHINA - Summary Kublai Khan continued the work his grandfather, Genghis Khan, had begun. But he also made significant land gains in China, achieving a prize that had eluded the Mongols for decades. Kublai Khan eventually rejected the harsh life of the steppes and built a luxurious palace complex in what is present-day Beijing; the poet Samuel Coleridge called it Xanadu. A visiting Venetian named Marco Polo recorded his impressions of the palace¹s grandeur: "the walls are of gold and silver. It glitters like crystal and the sparkle of it can be seen from far away." The Khan had many concubines and the women in his court held great sway over him. When Kublai's senior wife died, he lost the will to rule and retreated into a life of increasing decadence. In 1368, the conquered Chinese seized the opportunity to regain their independence. EGYPT - Summary After the rule of Kublai Khan ended, others followed China's lead and challenged the myth of Mongolian invincibility. The Mamluks in Cairo, Egypt, were the first soldiers to halt the Mongol military advance west. Their leader was a man called Baybars, who, like Genghis, excelled on the battlefield. He led an elite mounted corps that trained on the polo fields. At the battle of Ain Julut, in Palestine, the Mamluks dealt the Mongols their first defeat in an Islamic area and were able to protect Islam from further Mongolian domination. While not a defeat for the Mongol army as a whole, this small-scale battle had great symbolic significance. Much of the architecture in Cairo today dates back to the Mamluk era when a secure empire ensured flourishing trade. Cairo remained a leading cultural center within the Islamic world. EUROPE - Summary Europeans who had contact with Eastern knowledge often embraced new ways of thinking. A scientific revolution resulted, as Europeans began to explore and test the laws of nature. Frederick II of Sicily conducted numerous experiments, including disemboweling men to see how their digestive systems worked. Working in Paris, France, and Oxford, England, Roger Bacon dissected human eyes. His discoveries contributed to the invention of spectacles. A new religious movement encouraged people to regard the natural world as a thing to be loved and studied rather than feared. But these innovative movements would be stalled in the following century as disease and climatic change wiped out much of the population. 14th Century – Century of the Scythe The 14th century was an age of dynamic interaction between the great cultures of the world. But some of the promise of the previous century was cut short by climate change, plagues, and peasant revolution. Even so, obstacles to progress in China, the Islamic world, and Christendom created opportunities for previously marginalized parts of the world. The empires of Mali and Java, for example, flourished in this period. The "scythe" of this century was death itself, which swept through many parts of the world, either by disease or through imperial expansion. For MILLENNIUM's filmmakers, the 14th century demonstrates an important aspect of world history: its dissynchronous nature. In other words, not all parts of the globe experience things simultaneously. Certainly this was true in the 14th century when Europe and China were laid low by disease, climatic change, and socio-political dislocation, even as in Africa (Mali), Central Asia (Uzbekistan), and Indonesia (Java) empires flourished. Segments – 14th Century EGYPT - Summary Cairo was one center particularly hard-hit by disaster. At ten times the size of Paris or London, Cairo was one of the greatest cities in the world. But it lost 20,000 people a day to a mysterious and devastating disease called the Black Death. The bubonic plague was a pest-borne bacterial infection, which originated in Central Asia and spread along the flourishing trade routes both to the East and West. Christendom was especially hard hit. People struggled to understand why the disease had struck. Many looked for scapegoats. Jews were massacred and heretics burned. But when people noticed that the Jews and heretics were also dying, they began to blame themselves instead, recognizing the plague as a scourge sent by God. China, the Islamic world, and Christendom were all held back from expansion while the disease ran its course. MALI - Summary Beyond the reach of the Black Death, other cultures flourished. In West Africa, where the great Sahara desert provided a barrier against disease spread from the north, the empire of Mali was busy trading its abundant gold for essentials such as salt. An Islamic traveler from Tangier named Ibn Battuta wrote at length about what he saw in the empire of Mali. The mosques, libraries, and schools of the region's cities were gathering places for Muslim intellectuals and became comfortably familiar to him. Ibn Battuta was particularly impressed by the humility of King Mansa Musa's subjects and their devotion to the Islamic faith. Among the Mongols, all men rode horses; by contrast, in Mansa Musa's army only a tiny elite of professional soldiers rode. The skill of these cavalry units enabled Mansa Musa to dominate large swathes of the desert and grasslands of west Africa. The gold that provided him with the means to support such a huge empire became well known as far away as Europe. It was said that when he went on pilgrimages to Mecca, his extravagances upset the economies of the towns he visited. UZBEKISTAN - Summary In Central Asia, another empire was able to flourish. A nomadic conqueror, known as Timur, laid siege to vast swathes of territory. He began life as a sheep rustler, then rose to become a leader of armies. Claiming Mongol descent, he aspired to rival Genghis Khan. But as a convert to Islam, he also saw himself as a champion of the faith. Using terror and slaughter, he created an empire that stretched from the Indian Ocean to the Mediterranean. He used his gathered wealth to build extraordinary monuments in Samarkand and Bukhara, inside present-day Uzbekistan. Timur's ambitions seemed to know no limits. Almost blind and too weak to walk, he set off on one last campaign to conquer China. But he died before the invasion could begin - and his empire did not survive his death. Timur's memory lives on among the people of Uzbekistan, who hail him as a national hero and a symbol of might. INDONESIA - Summary Across the Indian Ocean, at the heart of the world's busiest trade routes, lay the island of Java, home to the kingdom of Majapahit. The regular monsoon winds of the Indian Ocean had helped sailors move East and West across the water for millennia. For half the year the winds blew in one direction and for the other half in the opposite direction. In between, ships idled in ports waiting to take off again. The main island of Indonesia, Java, was one such stopover point. It was also an important provider of specialized woods, spices, and rice. Much of Java's culture had its roots in India. Buddhism and Hinduism had mixed with local Javanese traditions to create hybrid faiths. Some of the traditions that originated in the 14th century are kept alive on a large island to the east of Java, called Bali. Here they tell the story of Hayan Wuruk, one of the kingdom's greatest leaders. Like others in this century, he had ambitions to create a huge empire stretching to China and India. But for the most part he was content to simply receive visitors from afar, offering them grand feasts and displays. Artistic performance was a way of entertaining and of honoring the gods. The island flourished under his rule. ENGLAND - Summary Back in Christendom, things were going from bad to worse. Not only were the people afflicted with the plague, but temperatures were plunging. A mini-ice age had struck. Icebergs floated farther south, and the northern seas grew treacherous. Marginal lands to the north were deserted and crops everywhere failed to grow. The poor suffered the most. What little food there was became astronomically expensive. Turning to their rulers for help, the poor were rewarded with oppressive laws and harsh taxes. Peasants across Europe began to challenge their rulers - rebellions erupted. The poor sought justice and equality, but their demands were largely refused. In the next century, some would decide to seek properity beyond the bounds of Christendom, across the oceans. 15th Century – Century of the Sail The fifteenth century was a century of far-flung exploration and ocean travel. During this "century of the sail" the peoples of many civilizations took to the sea and risked sailing with the winds. With the hardships of the previous century behind them, cultures around the world began to expand. For those with access to water and the technology to exploit it, great trade benefits awaited. The states that lined the coasts of maritime Asia developed the most impressive and mature sea-going technologies. But the fastestgrowing empire of the fifteenth century was land based; in the Americas, the Aztecs developed a civilization rivaled in speed and scale by only the Ottoman Empire. The maritime accomplishments of coastal societies in Asia and Mediterranean Europe during the century of the sail increased trade opportunities and moved both people and goods across continents. The Ottomans expanded by sea within the Mediterranean and proved that a land-based people could adapt to a sailing culture. The Aztecs, with their entirely land-based empire, provided a point of contrast to the ocean-based empirebuilding occurring elsewhere around the globe. As European sailors learned how to ride the winds of worldwide exploration, ocean travel would from this century onwards be synonymous with empire building. Segments – 15th Century CHINA - Summary China began to recover from the plagues and famines of the fourteenth century and turn her energies to maritime expansion. China was best equipped to expand, with technologies far exceeding those of her rivals. Ambitious expeditions left the shores of Asia during the reign of Emperor Yong Le, led by the eunuch Admiral Zheng He. For nearly three decades, Zheng He set sail with fleets as large as 200 ships and with crews totaling 27,000 men. The ships were some the largest wooden vessels ever constructed, over 400 feet long and 180 feet wide. They were powered by twelve bamboo sails on nine masts and could sail at any angle to the wind. While some claim these expeditions aimed to determine whether there was anything in the world China did not possess, others say the motives of the voyages were unclear. The fleets traveled to points all around the vast Indian Ocean, exchanging gifts with people they met, returning with exotic animals and goods. The expeditions were eventually abandoned; perhaps Confucian scholars decided nothing brought back was of use to China. China entered a period of self-created isolation. ITALY - Summary Western Christendom began to recover from the plague, and European culture experienced a "re-birth" or renaissance. The Renaissance was arguably dependent on sea links between Italy and Atlantic Europe as well as with Constantinople and other major ports around the Mediterranean. Improved and extended maritime connections between Italy, Alexandria, and Cairo ensured the import of exotic spices, clothes, and artifacts from the East. A few private, influential families vied with one another to show off their newfound wealth and stimulated progress in art and architecture. Ambitious new buildings sprang up, works of decorative art were commissioned, cathedrals were adorned with beautiful new frescoes, and artists devised new methods to portray it all on canvas. Italy's strong demand for luxuries and spices in turn inspired the sea voyages of Spain and Portugal. These two countries were on the periphery of Europe and were desperate to gain access to wealth. Trading goods with countries like Italy could provide it. CENTRAL AMERICA - Summary In the Americas, the Aztecs created a vast empire without the use of wind-powered crafts or water-based trade; the Aztec civilization was entirely land-bound. The heart of the Aztec empire was the city of Tenochtitlan, a huge, vibrant island in the midst of a swampy lake. From this city the Aztecs controlled thousands of outlying settlements, demanding the tribute which helped keep the main city provisioned and viable. The children of elite citizens were reared to be part of a disciplined warrior class. The warriors maintained the Aztecs' control over conquered peoples. The constant conquest of new peoples was also essential to supply sacrificial victims for offerings to the gods. The Aztec civilization would thrive until the arrival of the Spanish in the next century. TURKEY - Summary The Ottoman people exploited both land and sea-based military technologies to establish a new and vigorous Muslim empire in formerly Christian lands. In 1453, Mehmet the Conqueror led a 100,000-strong army towards Constantinople. Constantinople was one of the richest cities in Christendom, as prosperous as Venice, Florence, or Milan. But Mehmet¹s army outnumbered the inhabitants 7 to 1, and his victory was complete. The conquest changed the fate of Constantinople forever. Mehmet saved the ancient Christian cathedral of Hagia Sophia from destruction, but converted it into a mosque. In addition, he built a vast palace - the Topkapi Sarayi - with kitchens capable of feeding 10,000 people in a day. It was laid out like a nomad's tent, but on a grand scale, and echoed the Ottomans' Turkish style of art and architecture. Other conquests allowed the domain of the Ottomans to grow. Their empire eventually stretched from the Danube in present-day Hungary to the Euphrates in present-day Iraq, straddling the Silk Road. Finally, the Ottomans successfully challenged the Venetian empire at sea, establishing their control over all but the western portion of the Mediterranean. PORTUGAL - Summary The sail changed the fortunes of Portugal and Spain, two sparsely populated maritime nations located on the Iberian peninsula. Merchants were motivated to find a new sea route to the east so they could bypass the many middlemen who imposed taxes and the Ottomans who now had a stranglehold on the important trade routes. The Portuguese edged their way south around the coast of Africa, despite some dangerous sailing waters. Bartolomew Dias rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1488. But Christopher Columbus was the only one willing to take the ambitious gamble of a direct westerly journey. No one knew what lay to the west of the Iberian peninsula, but many feared the expanse of ocean was the domain of monsters and serpents. By Columbus' calculation, travelling west would eventually bring him to Japan where he would secure exotic goods to sell. The trade winds carried him to in San Salvador Island on October 12, 1492. He discovered new territories and brought two very separate parts of the world together for the first time in history. But the real triumph was reserved for Vasco de Gama, who 7 years later actually reached India and the Orient by sea. Expansion and subsequent colonization by the Spanish and Portuguese would forever change the course of history. 16th Century – Century of the Compass In the 16th century the world became an arena of competition between aggressively expanding empires and fiercely evangelical religions. New empires were created across oceans and continents by dynamic civilizations determined to influence cultures very different from their own. In this Episode, European maritime imperialism is set in the context of Russian, Chinese, and Japanese empire-building. The reach of global imperialism is evoked through the content of a cabinet of curiosities. The compass was a technology that made these ambitions possible. While the compass pointed the way for Spanish penetration of the Yucatan, Russian expansion across Asia, Japanese forays in Korea, and the Moghul thrust into India, it did not provide any direction in the way that the exchanges between peoples were conducted. In most cases, when peoples of differing cultures met face to face the results were often misunderstanding, suspicion, and bloodshed-not unlike present-day anticipations of encounters with aliens from other planets, with. Without a compass to direct the encounters, force alone usually determined the outcomes. In the Yucatan Peninsula, the Spanish overwhelmed the native Maya, and in Siberia the Russians overwhelmed the indigenous tribes. The weakness of the Japanese fleet led to continued isolation for Koreans and Japanese alike. In India, Muslim Moghuls encountered a strong Hindu cultural tradition, ultimately producing a Muslim-Hindu cultural mix rather than cultural submersion. Segments – 16th Century MEXICO - Summary In Central America, the Mayans and their Spanish conquerors struggled for souls. Diego de Landa, a Franciscan friar sent by the Spanish to the present day Mexican province of Yucatan, was a keen chronicler of Mayan culture. He spent time with Mayan villagers, learning to speak different dialects and adopting local customs. But equally, he was a zealous Catholic who baptized thousands of Mayans a day to "save their souls." Trouble began when he discovered that the converted Maya continued to worship their own idols. Enraged by the apparent double standard, de Landa began to interrogate villagers, then torture them. Over a three-month period some 4,500 Mayans, including chiefs and elders, were imprisoned and tortured. A new bishop arrived to calm the hysteria; de Landa was condemned for his actions. Although he managed to clear his name with the Spanish authorities, even today he is loathed by Mayans for his brutal repression. RUSSIA - Summary The foundations for modern-day Russia were laid in the 16th century. Russian expansion pursued by Ivan the Great was finally pushed beyond the Ural Mountains by Ivan the Terrible. The fur trade was very important to the Russians, but the trade all lay to the East, in the vast reaches of Siberia. Kazan lay between Russia and the supply routes. When Kazan was conquered in 1553, it was celebrated by the construction of St Basil's Cathedral in Moscow. Its famous cupola domes represent Kazan turbans, one for each chieftain killed in the siege. In Siberia, Cossack mercenaries hired by Ivan moved steadily across the freezing wasteland, attacking local rulers and terrorizing indigenous peoples. Domination of the fur trade was finally achieved, and Moscow grew rich on the proceeds. But towards the end of his life the strains of empire unhinged Ivan the Terrible, and a reign of terror was instituted. JAPAN - Summary Japan had for centuries remained relatively isolated from the world, surrounded by treacherous seas. But in the 16th century a ruler emerged who was determined to cross them. He was Toyotomi Hideyoshi, a peasant soldier known as "The Bald Rat." He has come to be considered the true architect of the Japanese nation and is still venerated in annual festivals. After centuries of anarchy and rivalries between warlords throughout Japan, Hideyoshi managed to unify the country and create a new state of affairs: internal peace. Then he declared his ambition to conquer China, via Korea. But the Koreans had developed the invincible turtle ship, which proved far superior to anything in the Japanese navy. Smarting from defeat, Hideyoshi retreated and spent his remaining years in a state of paranoia, devoted to his only son Hideyori. But after his death, Hideyoshi's generals rebelled. Hideyori and his mother committed suicide. Japan once again closed itself off from the outside world. INDIA - Summary The Moghuls had imperial ambitions, and these produced long-lasting effects. Originating in Central Asia, the Moghuls (descendants of the Mongols) under the teenage ruler Babur began conquests in Samarkand. Failing here, they moved East into Kabul (present-day Afghanistan) and then finally central India. Babur's daughter Gulbadan was, like her father, a strict Moslem. She and other women in the harem were shocked when they encountered the customs of the Hindis in India. Gulbadan would never adjust, but Babur's grandson Akbar the Great proved more open-minded. Marriage alliances brought him lands and loyalty, and in return he allowed a diversity of beliefs to flourish in the Moghul empire. He even built a special house of worship where representatives from all the different creeds were encouraged to discuss their faiths. Later on, buildings like the Taj Mahal came to symbolize this fusion of cultures, a characteristic of India which endures to the present day. EUROPE - Summary The 16th century was a critical point in history as the varied cultures of two great landmasses-the Americas and Eurasia/Africa-finally came into contact with one another. Fear and greed dominated many of these contacts, but wonder also played a part. Explorers and conquerors brought strange artifacts back to Europe, such as armadillos, corn, parrots, and canoes. These were gathered together in what became known as Wunderkammer, or Cabinets of Curiosities. Primarily the obsessions of scientists or princes, these contained oddities purchased from world travelers. Emperor Rudolf II of Prague packed over 20,000 exhibits and specimens into just four rooms. Not only did the collection inspire wonder in the onlooker but it signified the worldwide reach of the ruler. They were the precursors of many of the museums of today. 17th Century – Century of the Telescope The 17th century was a century that favored communities with access to the Atlantic, particularly those in northern Europe. The first refracting telescope, invented by Dutch lens grinders in 1600, was a useful tool for European cultures looking to expand across the ocean. Compelled by choice and by necessity, some Europeans set sail to establish precarious colonies across the Atlantic. These settlements marked the beginning of the enduring European and African cultural influence in the Americas. Goods first trickled, then flowed back into Europe from the Americas and southeast Asia. The Dutch grew rich from trade, ushering in a brief "Golden Age." The telescope also symbolized the rise of Western scientific endeavor and the technical superiority that the West would later enjoy. The lens symbolizes the extraordinary scientific advances made by the Europeans in the 17th century. Among those inventions was the telescope (1600) which became an instrument vital to European expansion overseas. This expansion led to colonization and growth of a lucrative trade in sugar and slaves in the Americas. It also led to a Golden Age in Holland, spawned by Dutch control of the rich East Asia spice island trade. The telescope brought sharp focus to the shifting world power center from China to Europe over the next few centuries Segments – 17th Century ENGLAND - Summary In the 17th century, scientists like Isaac Newton transformed people's understanding of the world. The telescope, and then the microscope, enabled gentlemen scientists in Europe to observe new facts. Europe's rulers were now willing to support scientific undertakings, realizing that knowledge was power. In England, after a bloody Civil War, gentlemen were freed from the demands of military service and were able to follow new pursuits. And those who were not born into high ranks now found the means and finance to rise independently. Isaac Newton studied the astronomy of Galileo and the philosophy of Descartes, and was a pioneer in mathematics. He found that the movement of ordinary objects was predictable. Made famous by his work, he was knighted and made president of a new Royal Society dedicated to learning. The new faith in the regularity of nature challenged superstition and provided the foundation for advances in European scientific endeavor for centuries to come. USA - Summary The telescope aided English expansion overseas. Keen to catch up with the Spanish and Portuguese in the New World, James I granted a charter to open up the Americas. In 1607, 104 men sailed to the coast of present-day Virginia. They expected to find quantities of gold and to get rich quick. Instead they encountered an unfamiliar environment and residents-the Powhatans-who were soon given reasons to mistrust the newcomers. Unreceptive to successful food-growing methods used by the Powhatans, the colonists proved unable to provide from themselves and most died. One self-elected leader, John Smith, held the colony together for a time, but was then mysteriously injured and returned to England to recover. The venture was on the verge of failure when "gold" was discovered in the form of tobacco. As demand for the crop in Europe grew, the future of the colony was assured. BRAZIL - Summary The Portuguese had already settled small numbers of people in the Americas, but during this century they brought in many more, this time from Africa. These were slaves, involuntary colonists of the New World. The ocean routes opened up in the previous century were used to transport hundreds of thousands of captured slaves from Portuguese colonies in western Africa to Brazil. The slaves were needed to grow sugar cane, a labor-intensive crop imported to and grown successfully in the fertile soil around Salvador in northeast. Plantation life was cruel, brutal and short. Demand for slaves was constant because so many died and women deliberately had very few children. Some slaves escaped to live in free communities in the hills. One of these, Palmares, boasted an army of over 5,000 soldiers. In present-day Brazil the legacy of the slave trade can be seen in African traditions preserved and still practiced. HOLLAND - Summary Another unlikely part of Europe grew rich on overseas trade. The Dutch used the telescope to sail to southeast Asia and establish dominance over supply routes for spices. The key to their success was distribution of spices by sea, which bypassed the more traditional trade routes. Goods which had previously enriched the East now led to the creation of booming stock market in Amsterdam. Like the Italian Republics of the twelfth century, the Dutch celebrated by building a new Town Hall. Rich and poor merchants commissioned portraits of themselves and the world in which they lived. A Golden Age had begun. But when decadence eventually set in, economic initiative shifted elsewhere. CHINA – Summary The newfound European confidence was felt in China. Here visiting Jesuits demonstrated the new European advances in astronomy. For centuries, the Chinese empire had led the world in science and technology. Now, the Jesuits spoke of a clock that could predict the movements of the stars. Intrigued, the Chinese conducted a test. An eclipse of the sun was predicted by both Chinese and European astronomers. The hour predicted by the Chinese came and went. Then, at the precise moment the Jesuits had anticipated, the eclipse occurred. Here was another example (European mapping being another) of Western science challenging Chinese superiority. A period of exchange opened up for a time. Chinese learning once again traveled back to Europe, influencing thinkers like Voltaire and Leibnitz who would in turn shape developments in the next century. 18th Century – Century of the Furnace The eighteenth century was the "century of the furnace" in a dual sense: the furnace of proto-industrial technology glowed brightly in China, India, and the West, and the furnace of political revolution set off sparks as well. New ways of thinking strengthened and disrupted Europe, while the American Revolution strained ties across the Atlantic between Europe and the colonies. India textile exports thrived, with thousands of workers mass-producing cotton, tea, and silk. However, by the middle of the century, the British East India company began its conquest of India-Britain was beginning to claim these riches. China, also confident about its economic prosperity, colonized new territories to the north and west. In the eighteenth century, two parts of the globe were seething with energy and change. In the West-in Europe and the Americas-adventurous expeditions struck out to remote corners of the world. New ways of thought based on the Enlightenment inspired revolutions that empowered the middle class. Nowhere was the empowerment of the common man more evident that in the West's growing appetite for goods on a mass scale. In the East, both India and China enjoyed the prosperity derived from their roles as producers and exporters. Textiles and spices from India and porcelain and tea from China moved west and both countries profited by this exchange. However, by the end of the century these states would be eclipsed by the productive power of European factories and by the colonial overlordships imposed by European states. In the nineteenth century, East and West would experience a different set of relationships in the context of a different world dynamic. 18th Century LAPLAND - Summary The furnace of ideas in Europe inspired extraordinary expeditions to remote corners of the world. Newfound confidence in the ability of and need for scientists to scrutinize the world led the French King Louis XV to sponsor one of the world's most expensive expeditions, an attempt to measure the shape of the earth. Two teams had to measure the distance between one degree of the earth's latitude. One team went to the equator and the other, led by Pierre de Maupertuis, to the Arctic Circle. The difference between their measurements would reveal whether the earth was a true sphere, was elongated, or was slightly flattened at the top and bottom. The project took a year, including two bitterly cold winters building signal towers and fixing measuring rods in the deep snow of northern Finland. When the results were collated, the teams discovered that the poles of the earth were slightly flattened-knowledge that was extremely useful to all navigators. PORTUGAL - Summary While scientists measured the earth, new rational ideas were also applied to society. Cities across Europe were shaped by new ideas. After an earthquake devastated Lisbon in Portugal in 1755, the city was rebuilt with broad squares and bold vistas laid out in an ordered geometric pattern under the supervision of Portugal's Prime Minister, Marquis de Pombal. The city became a symbol of the Enlightenment, a movement that fostered a belief in reason and the scientific method. The authority of the past was rejected, while moral authority was derived from reason. Mozart's opera The Magic Flute celebrated this new cult of reason. A revival of interest in the game of chess illustrated Enlightenment ideals of equality: in chess a mere pawn can overthrow the king. USA/France - Summary The ideas brewing in Europe inspired rebellion in the British colony of America. Thomas Jefferson's house, Monticello, symbolized his allegiance to the spirit of the Enlightenment. His house also symbolized a new sense of American culture. Its architecture and decoration derived from European classical motifs but displayed distinct differences. Like other settlers in the colony, he felt little allegiance to the British. Inspired by Thomas Paine's Common Sense (a pamphlet which attacked the authority of the British King) and by other grievances, he wrote the Declaration of Independence. The British declared the colony in rebellion and war ensued. The greatest naval power in the world was eventually defeated at Yorktown, Virginia in 1781 by the partnership of the French military-seeking revenge for the Seven Year's War-and George Washington's troops. In fact, there were more French at Yorktown than Americans. Without the French army and navy, victory would have been impossible. With the end of the American Revolution, British dominion over the colony ended and the Republic of the United States of America was born. The furnace of ideas also inspired the French Revolution of 1789, but the outcome was far bloodier. Enlightenment ideas of democracy--the rights of ordinary people and the value of unsophisticated cultures-- inspired revolutionary sentiments. The American revolution had demonstrated that with a closer link between the rulers and the people it was possible to overthrow Great Britain. While many of the revolutionary ideas in France were provoked by a desire for power, the acute food shortages experienced by the poor also contributed. King Louis XVI lived in extraordinary luxury in Versailles. His wife, Marie Antoinette, dressed up as a shepherdess and tended a flock provided for her in the grounds of the palace. Such pretensions to poverty enraged an already miserable population. A rebellion began in 1789. The King and Queen were the first to be beheaded. As mob rule took over, many more died during a period known as the Reign of Terror. INDIA - Summary In the East, India and China possessed two of the wealthiest and most productive economies in the world. India was the world's biggest exporter of textiles, and merchants worldwide coveted this wealth. As the Moghul empire disintegrated, the British seized the opportunity to gain some advantage. British traders in Bengal helped defeat insurrections and were rewarded with a share of tax revenues. But in the southern state of Mysore the British were refused a stake in the economy. The state's elite cavalry, ruled by Tipu Sultan, roundly defeated the British and their Indian allies. A local drama portrays Tipu Sultan as a hero and records how the British conspired against him. In 1799, the British, together with Tipu's enemies, finally defeated the Mysore troops. Within fifty years, the British established colonial rule over the whole of India. The products and profits of Indian technology moved westward. CHINA - Summary Eighteenth-century China was also a furnace of industry. Ambitious colonization to the west and the resettlement of millions of peasants to the rich agricultural lands of Sichuan expanded the empire to its current border. Crops brought from the New World prompted an agricultural boom. Cottage industries also multiplied into industrial scale. Demand for cups and teapots for tea-drinking stimulated a manufacturing boom and porcelain was produced on a vast scale. Exports to Southeast Asia and the West also swelled China's merchants' coffers, making it the richest nation on earth. British missions brought European goods to tempt the Chinese into free trade agreements, but the offerings were met with indifference. Though China imported fur, silver, gold, and other metals, many in China claimed that there was nothing the country needed that it could not produce itself. Emperor Qianlong eventually opened up some trading houses to the foreigners, a move the Chinese would live to regret. 19th Century – Century of the Machine Industrialization altered the world's balance of power in the nineteenth century. During the "century of the machine," Western powers established world empires by means of technological superiority and became more powerful than the big-sister civilizations of China, Islam, and India. Other cultures tried to resist the influence of the industrial powers but ultimately failed, losing ground to new modes of living. The machine was truly a new phenomenon in world history, wedding science and technology. Until the nineteenth century, science had been closely tied to religion and practiced by many societies in the abstract, while technology was a continuum of everimproved tool-making. But when science was applied directly to the creation of practical tools, the results were astounding. Western Europe, building on its own classical heritage and that of Islamic, Chinese, and Indian science, pioneered the application of scientific rationalism to mechanical creations. The result was a revolution in which the source of productive power was transferred from man to machine. The steam engine, one of a series of new power sources, gave economic, political, and social power to those who possessed its mechanical secrets. In this way, Western Europeans began to dominate the Americas, and also Asia and Africa. This domination was not just physical, in the form of empires, but extended to world-view and religion. Europe spread the belief that the development of science and technology was equivalent to human progress and enlightenment. Despite these imperial over tones, science and technological achievements have proven irresistible to most people the world over, perhaps due to the promise of better living conditions. Segments – 19th Century BRITAIN - Summary In nineteenth-century Britain, engineers and inventors became heroes. Richard Trevithick was one of the first hero-engineers; he created a locomotive powered by steam. This technology was then applied to boats, and soon paddle steamers were crossing the Atlantic Ocean, carrying thousands of migrants to new worlds. Oceans previously crossed at great risk, particularly the Pacific, could be spanned easily by the latter part of the century. A world-wide network of transport evolved, joining continents together by rail and steam. An itinerant preacher, Thomas Cook, began a global tourism business. The newly industrialized powers also had further means to expand, colonize, and control the world. ENGLAND - Summary Charles Darwin, a young scientist conducting a world survey for the Royal Navy, developed astounding new theories about evolution. These ideas were published as The Origin of Species, in which Darwin suggested that species, including humans, changed over time as they adapted to local environments. Humans, he said, were the descendants of apes. While Darwin's arguments horrified the religious establishment, others found his ideas appealing and adapted them for other uses. The doctrine of "survival of the fittest" was interpreted as justification for the nations of the West to dominate and conquer other less "fit" cultures. In the last two decades of the century, Africa became the victim of a wholesale European colonial take-over. USA - Summary Nineteenth-century mechanization also contributed to the drift of American settlers westward. Steel plows and railroads made settlement of the prairies easier. The native inhabitants resisted the new settlers; using guns and horses brought to the New World by Europeans, the Plains Indians proved to be difficult to displace. But the settlers turned their repeating rifles against the life-source of the Indians: millions of buffalo were slaughtered and an entire ecosystem was destroyed. Defeated at last, the Indians were confined to unwanted land, prisoners in their own country. The conflict would be recreated in theatrical fantasies such as the Wild West Show, establishing a myth of cowboys and Indians. CHINA - Summary China¹s position as a world-trade power changed in this century when the British used new steam gunboats to defeat China in the Opium Wars. China had become a vital trading partner for the British, who were devotees of Chinese silk, porcelain, and, above all, tea. To correct the trade imbalance, the British needed to find a product that the Chinese wanted. The British decided to exploit poppy crops in their Indian colony to supply the drug opium to every part of China. The Chinese protested, as they were already weakened by the drug, but to no avail. When the Emperor's Commissioner, Lin Zexu, locked up 350 British merchants in their factories and ordered thousands of balls of opium destroyed, war ensued. But the British were victorious. They forced China to pay for the war and hand over five ports, including Hong Kong. China was opened up to European powers and to Western ways. EUROPE - Summary Industrialization changed the conditions of many people's lives. Steam engines powered not only trains and ships, but also looms. Together with the furnace, these engines transformed production. Factories sprang up around the industrialized world, enriching business tycoons. But the centralization and mechanization of production convulsed society. Towns grew overcrowded, riddled with slums and disease. People worked long hours in noisy, filthy, and degrading conditions. For some, manufactured goods improved living conditions, but others were stirred to protest the factories and the hardships they created. Men, women and children fought for their rights and called for political representation. These same social dynamics would come to dominate more people's lives in the century to follow. 20th Century – Century of the Globe During the twentieth century, the "century of the globe," humans entered space, and for the first time were able to see from afar the planet they call home. This achievement resulted from remarkable developments in science and technology. While some of these developments were used in war, creating killing fields of mass destruction, others completely revolutionized physics, art, medicine, and communications. These advances, in turn, prompted a population explosion, mass migrations, and the creation of huge urban megalopolises. The ease of global transportation and communication led to the creation of a world culture largely modeled on American styles of dress, music, and entertainment and fed by the twentieth-century propensity to change, innovate, and market. The tempo and breadth of technological change makes the twentieth century stand out as a turning point in world history. Technological development may be akin to other great human achievements like standing upright, tool making, the agricultural revolution, metallurgy, and industrialization. Global communication and transportation systems have made the globe one and have heralded a new era in politics, economics, social systems, and culture. The third Millennium may well be the Age of Space when humans fan out across the cosmos as they did across the globe so many millennia ago. It would have been difficult to predict that a century that began with world wars would end with international celebration. Such is the human drama that is reflected in the pages of history and in the video episodes of this MILLENNIUM series. Segments – 20th Century FREUDIAN TIMES - Summary Twentieth-century science investigated both the internal world of the mind and the external world of physics. While psychoanalyst Dr. Sigmund Freud explored unconscious and subconscious motives for behavior, Albert Einstein c ompletely revolutionized physics by challenging established Newtonian laws of movement, motion, and matter. Einstein and others suggested that the laws of physics work according to principles of relativity rather than fixed laws, that there are even smaller units of matter than atoms, and that change can occur randomly and in "leaps". The theoretical world of science and the unseen world of the mind had a profound impact on art. Pablo Picasso and others fragmented reality by painting objects and people from multiple perspectives at once. Innovations in science and art, along with the devastating twentieth-century world wars, bred a sense of introspection and uncertainty. EUROPE - Summary Twentieth-century world wars, ideological fanaticism, and genocide smashed nineteenth-century optimism and belief in human progress. In World War I, armies exploited technologies of death like poison gas and the automatic machine gun. By war's end, Europe was scorched physically and scarred mentally, and her world hegemony foundered. Further carnage occurred in World War II, a war that began with the Japanese invasion of China that caused millions of deaths and that ended with the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki killing millions more. Meanwhile, communist and fascist ideological fanaticism led to Siberian death camps, famine prompted by forced collectivization in Russia and China, and Nazi genocidal policies against Jews. After World War II and during the Cold War that followed it, ever more dangerous weapons like nuclear bombs cast a pale of fear over the world's population and stood as a threat of Armageddon. No less fearsome were the less sophisticated weapons of war like machetes and rifles that were used in ethnic and ideological conflicts in Rwanda, Cambodia, and other states. USA - Summary Population increases, faster and cheaper modes of transportation, and the end of European empires led to mass population movements in the twentieth century. As populations soared, people sought opportunities in wealthier countries and in cities where there were more opportunities for work. Relationships between imperialist powers and their colonies provided many people with the legal means to move. In America, immigration from neighboring Spanish-speaking countries by people searching for jobs and a better life transformed American culture. NORTH AMERICA - Summary In many ways, the twentieth century belongs to America. Americans developed, exploited, and marketed worldwide new technologies like the automobile, telephone, television, and computer. They also exported their culture in the form of films, music, clothes, and sports. American corporations also became "multinational" by establishing headquarters in a vast range of countries. American dollars followed and became the de facto world currency. JAPAN - Summary The post-World War II economic boom affected Asia as well as Europe and America. With the help of American aid, Japan rebuilt and began to challenge the American export market in the field of cars and electronics. The economies of other Asian "dragons" like Singapore, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and South Korea also grew at extraordinary rates. After fifty years of economic hardship under communist experimentation, the progressive policies of Den Xiaoping began to revitalize the economy of China. Meanwhile, ethnic Chinese overseas used their considerable capital to nurture growth back in China. Many predict that the twenty-first century, much like the tenth century that began the Millennium, will belong to China.