DRAFT

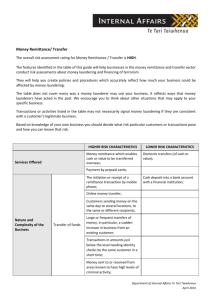

advertisement