6 ledger accounting

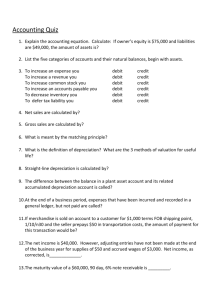

advertisement

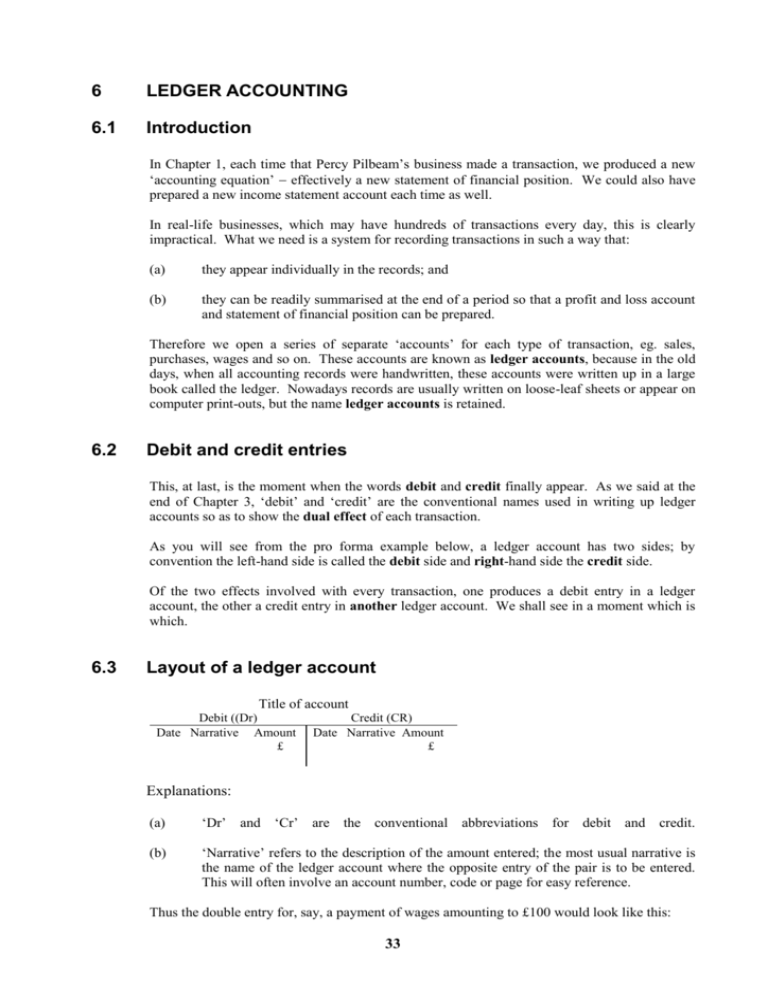

6 LEDGER ACCOUNTING 6.1 Introduction In Chapter 1, each time that Percy Pilbeam’s business made a transaction, we produced a new ‘accounting equation’ effectively a new statement of financial position. We could also have prepared a new income statement account each time as well. In real-life businesses, which may have hundreds of transactions every day, this is clearly impractical. What we need is a system for recording transactions in such a way that: (a) they appear individually in the records; and (b) they can be readily summarised at the end of a period so that a profit and loss account and statement of financial position can be prepared. Therefore we open a series of separate ‘accounts’ for each type of transaction, eg. sales, purchases, wages and so on. These accounts are known as ledger accounts, because in the old days, when all accounting records were handwritten, these accounts were written up in a large book called the ledger. Nowadays records are usually written on loose-leaf sheets or appear on computer print-outs, but the name ledger accounts is retained. 6.2 Debit and credit entries This, at last, is the moment when the words debit and credit finally appear. As we said at the end of Chapter 3, ‘debit’ and ‘credit’ are the conventional names used in writing up ledger accounts so as to show the dual effect of each transaction. As you will see from the pro forma example below, a ledger account has two sides; by convention the left-hand side is called the debit side and right-hand side the credit side. Of the two effects involved with every transaction, one produces a debit entry in a ledger account, the other a credit entry in another ledger account. We shall see in a moment which is which. 6.3 Layout of a ledger account Title of account Debit ((Dr) Date Narrative Amount £ Credit (CR) Date Narrative Amount £ Explanations: (a) ‘Dr’ and ‘Cr’ are the conventional abbreviations for debit and credit. (b) ‘Narrative’ refers to the description of the amount entered; the most usual narrative is the name of the ledger account where the opposite entry of the pair is to be entered. This will often involve an account number, code or page for easy reference. Thus the double entry for, say, a payment of wages amounting to £100 would look like this: 33 Cash £ 7.1.X4 Wages £ 100 Wages expense 7.1.X4 Cash £ 100 £ The next thing, of course, is to understand which entries go on which side (yes, it does matter). 6.4 The meaning of debit and credit We said that debit and credit were merely conventions; it is true that the names themselves mean little and have come a long way from their Latin origins. But what is important is that certain entries go on particular sides. The following is of vital importance throughout your accounting studies, so try to commit it to memory. A debit entry represents: A credit entry represents: (a) an increase in the value of an asset; (a) or or (b) a decrease in the amount of a liability; (b) or a decrease in the value of an asset; an increase in the amount of a liability; or (c) an item of expenditure (c) an item of income. Remember that: (a) Every transaction made by a business will involve two of these effects, one debit and one credit. (b) For every debit entry there must be a corresponding credit entry, and vice versa. Try to work out what the entries for cash and wages in paragraph 6.3 signify. The credit entry in the cash account means a decrease in the value of an asset and is therefore a credit. The debit entry in the wages account means an item of expenditure and is therefore a debit. 34 6.5 Link with the final accounts Before we put all this into practice with an example, a reminder to you not to lose sight, in a sea of double entry, of what bookkeeping is ultimately trying to achieve. The purpose of bookkeeping (Chapter, paragraph 1.4) is to enable a business’s transactions to be summarised at the end of a period so that accounts can be produced. These summaries are the statement of financial position, showing assets and liabilities and the income statement, showing expenditure and income. 6.6 Example: Percy Pilbeam revisited To enable you to see how ledger accounting works, we will first write up Percy Pilbeam’s first month’s transactions (as in Chapter 3), explaining what happens with each one as we go along: we will then ask you to write up a series of transactions in his second month, so that eventually you can produce a set of accounts for the two-month period. By the time you get to the second month, you should be able to see that, for any number of transactions, ledger accounting is much quicker than producing an accounting equation (or statement of financial position) after each one. So here we go with Percy’s first month. Step 1 He opens a business bank account with £10,000 in cash. First of all, what is the dual effect? (This, of course, is the clue to what the double entry is going to be in the ledger accounts The business has: (a) £10,000 cash (b) £10,000 capital. Taking cash first, what is it? (Asset, liability, income or expenditure). An asset. An increase in the value of an asset is a debit entry (paragraph 6.4 above). So we make a debit entry in the cash account. Capital is the amount owed by the business to its proprietor. So what is it? (Asset, liability, income or expenditure in the business’s books, remember). A liability (the business owes the liability to the proprietor). An increase in the value of a liability is a credit entry. So we make a credit entry in the capital account. Note We refer in the narrative of the ledger account to the other account effect by the transaction. 35 Cash £ 10,000 Capital £ Capital £ £ 10,000 Cash Instead of doing an accounting equation, we now go straight on to the next transaction. Step 2 The business buys fruit from Wooster Wholesalers for £4,000, paying cash for it. Dual effect: (a) £4,000 inventory (b) £4,000 less cash. When we looked at this transaction in Chapter 3, we recorded the purchase of fruit as an increase in inventories (an asset). So it is: but because it will soon be sold (we hope) we don’t show inventories as an asset except at the end of a period, when we create a inventories account for the amount of inventory on hand then. Instead, when a business buys and sells inventory we record these transactions as purchases and sales. Since purchases are clearly an expense, this means a debit entry in the purchases account. The other side of the double entry is a decrease in cash; since cash is an asset this means a credit entry in the cash account. Cash Capital £ 10,000 £ 4,000 Purchases Purchases Cash £ 4,000 £ Step 3 The business buys £2,000 worth of vegetables from Wooster Wholesalers on credit. Remembering what we have just said about inventories and purchases, what is the dual effect of this? (a) Purchases of £2,000 36 (b) A payable of £2,000. This means, again a debit entry in the purchases account (expenditure): the other side, the liability, means a credit entry in an account for payables. Purchases Cash Payables £ 4,000 2,000 £ Payables £ £ 2,000 Purchases An alternative to a general ‘trade payables’ account would be an account specifically for Wooster Wholesalers. Later in your studies, you will find that most sizeable businesses have both a total trade payables account (or ‘trade payables control account’) and individual accounts for each payable. Exactly the same thing applies, not surprisingly, to receivables. Step 4 The business sells all the fruit for £5,000 cash. Once again, remember what we said about inventories and purchases; the same applies to sales, and this should actually make it easier to understand the dual effect of the transaction and to make the ledger account entries. (a) Sales of £5,000 (b) £5,000 more cash. If a purchase is an expense, a sale must be an item of income; we must therefore make a credit entry in the sales account. Cash an asset increases, so we debit the cash account. Sales £ £ 5,000 Cash Cash Capital Sales £ 10,000 5,000 £ 4,000 Purchases The profit element (£1,000) is included in sales, though not of course in purchases, and this will eventually come through in the profit and loss account. 37 Step 5 The business incurs, and pays, an electricity bill for £200. Dual effect: (a) £200 less cash (b) An electricity expense of £200. It should by now be easy, for you to see that we must debit the electricity account (an expense) and credit the cash account (decrease in the asset). Electricity £ 200 Cash £ Cash £ 10,000 5,000 Capital Sales £ 4,000 200 Purchases Electricity Step 6 The business buys a Ford van for £4,000 cash. Dual effect: (a) A non-current asset of £4,000 (b) £4,000 less cash. Double entry: Debit non-current asset account Credit cash account because the non-current assets are increasing, and cash is decreasing. Non-current assets Cash £ 4,000 £ 38 Cash £ 10,000 5,000 Capital Sales £ Purchases 4,000 Electricity 200 Non-current assets 4,000 Step 7 Percy draws £500 cash out of the business. Dual effect: (a) £500 less cash (b) £500 drawings (reduces capital). The asset ‘cash’ decreases, so we credit the cash account. Think of drawings as a decrease in capital (the liability to the proprietor), not as an expense. We could debit the capital account, but because there might be several drawings made during a period, it is more convenient to open a separate drawings account. Drawings Cash £ 500 £ Cash Capital Sales £ 10,000 5,000 £ Purchases 4,000 Electricity 200 Non-current assets 4,000 Drawings 500 These were the transactions during Percy’s first month of trading. If we now list the transactions of his second month, see if you can write them up, using the ledger accounts provided, without looking at the answers. 6.7 The second month’s transactions (1) Sold all the vegetables bought in the first month for £2,500 cash. (2) Bought £6,000 worth of fruit from Wooster Wholesalers on credit. (3) Bought £3,000 worth of vegetables for cash. (4) Bought £500 worth of prunes from M Bassett on credit. (5) Sold all the fruit bought in (2) above for £7,500 on credit to R Glossop. (6) Sold half the vegetables bought in (3) above for £2,000 on credit to Jeeves & Co. 39 6.8 (7) Paid Wooster Wholesalers £3,500. (8) R Glossop paid for his fruit in full. (9) Received (but didn’t pay yet) a bill for £800 rent from S Malloy, his landlord. (10) Paid £200 for his telephone bill. (11) Received rent of £100 cash from F Bloggins for the use of his garage. (12) Drew £400 cash out of the business. (13) Bought a cash register for £300 on credit from Sioux Business Services. The entries for the second month You will find below all the ledger accounts you need to enter the second month’s transactions, with the first month’s transactions already entered. Take one at a time and fill them in. Remember for each one there must be a debit entry and a credit entry. The answers are on the pages following your version. Don’t look at them until you’ve finished! Note Don’t bother yet to add up the figures in the accounts. We are coming to this in the next chapter. Cash Capital Sales £ 10,000 5,000 £ Purchases 4,000 Electricity 200 Non-current assets 4,000 Drawings 500 Capital £ £ 10,000 Cash Purchases Cash Payables £ 4,000 2,000 £ Sales £ £ 5,000 Cash 40 Payables £ £ 2,000 Purchases Electricity Cash £ 200 £ Non-current assets Cash £ 4,000 £ Drawings Cash £ 500 £ Receivables £ £ Rent payable £ £ Telephone £ £ Rent receivable £ £ 41 6.9 Answers Cash Capital Sales Sales Receivables Rent receivable £ 10,000 5,000 2,500 7,500 100 Purchases Electricity Non-current assets Drawings 7,500 Purchases Payables Telephone Drawings £ 4,000 200 4,000 500 3,000 3,500 200 400 Capital £ £ 10,000 Cash Purchases Cash Payables £ 4,000 2,000 Payables Cash Payables 6,000 3,000 500 £ Sales £ Cash £ 5,000 Cash Receivables Receivables 2,500 7,500 2,000 Payables Cash £ 3,500 £ 2,000 Purchases Purchases 6,000 Purchases 500 Rent 800 Non-current assets 300 42 7,500 2,000 Electricity Cash £ 200 £ Non-current assets Cash Payables £ 4,000 £ 300 Drawings Cash £ 500 Cash 400 £ Receivables Sales £ 7,500 Sales 2,000 £ 7,500 Cash Rent payable Payables £ 800 £ Telephone Cash £ 200 £ Rent receivable £ £ 100 Cash 43