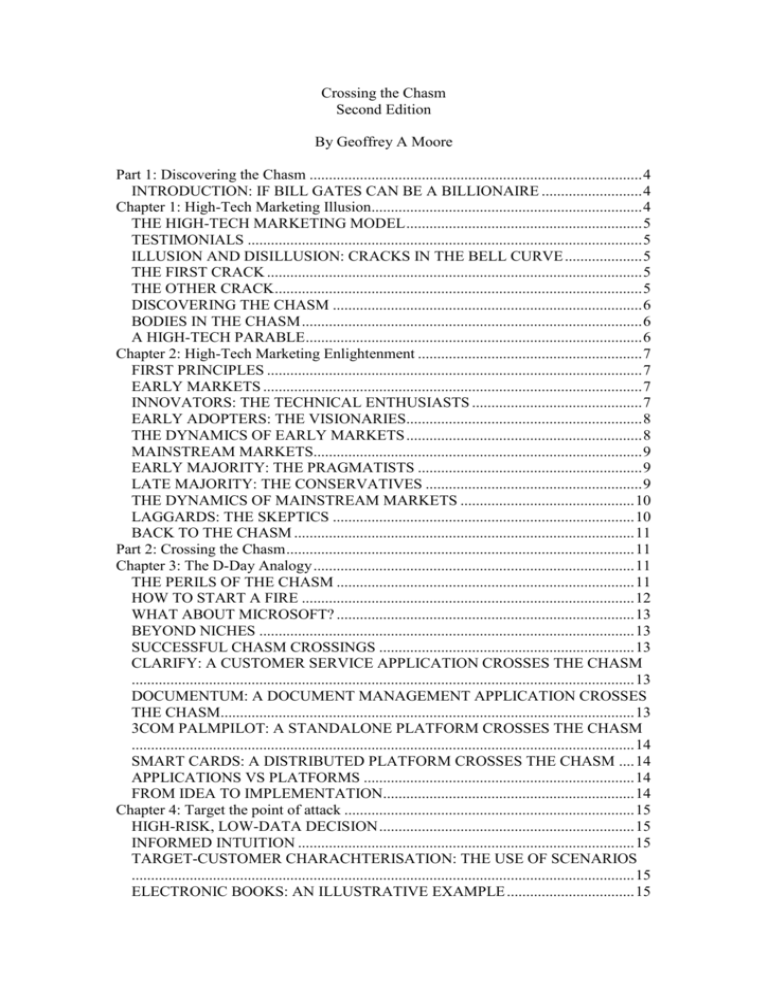

Crossing the Chasm

advertisement