Internationalization Intent Levels

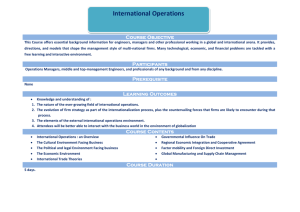

advertisement

Internationalization Intent Model by Mustafa Burak Guclu IBA8010-S1-SP-2009 Dr. Louise Kelly ABSRACT The study contributes to the existing research by exploring how firms choose the right level of intent in relation to business environments of foreign markets. Potential determinants are derived from traditional internationalization process theory as well as more recent literature on knowledge management; including the resource-based view. Building upon these literature streams a conceptual model and specific propositions are developed concerning the pattern and progression of knowledge and resources development within the foreign markets. I discuss implications of the proposed conceptual model for both research and managerial practice. 1 INTRODUCTION Internationalization theories study the nature and determinants of the process by which companies develop international operations (Buckley and Ghauri 1993; Welch and Luostarinen 1988; Cavusgil 1984; Johanson and Vahlne 1977). According to internationalization process model, firms learn new foreign market knowledge incrementally through the commitment of resources to do business in specific markets. Foreign market knowledge furthermore affects how current activities are accomplished (Ling-Yee, 2004). The learning process was found to be critical important particularly that has grown from the actual experience of internationalization, resulting in experiential knowledge (Johanson and Vahlne, 1977). Previous studies on internationalization process have underlined experiential knowledge leading to organization’s performance but ignored different forms and level of market knowledge in an organization’s knowledge base, and the influence of this knowledge in the development and exploitation of organization capabilities (Maheran, Mohammad & Mohammad). There is also very limited attention on the link between “internationalization theories”, knowledge-based view theory and other strategic theories at both the conceptual and practical level (Welch and Welch, 1996). In this study I use knowledge management theory for examining a firm’s tendency to invest in future foreign market activities. Whereas prior research has often emphasized a firm’s degree of internationalization as its level of export, De Clercq, Sapienza, and Crijin (2005) defines “internationalization intent” as a firm’s propensity to expand its cross-border activities in terms of the intensity (for example, level of export) and the scope (for example, number of countries to 2 which the firm exports) of such activities. The contribution of the study lies in creating a measure for market knowledge gap versus resource commitment gap as an antecedent of internationalization intent. This includes activities aimed at exploiting existing knowledge and resources compared to exploring new knowledge and resources with regard to domestic and foreign markets. 3 THEORATICAL BACKGROUND This paper builds upon three major theoretical streams: internationalization, knowledge management, resource-based view. Internationalization Extensive interest in the internationalization process of firms has escalated many different approaches and models to try to explain how firms enter foreign markets. There are a variety of models in the field of internationalization, both descriptive e.g., the Network model and predictive e.g., the Uppsala model, as well as static and dynamic (Hansson, Sundell & Öhman, 2004). In the Network model the long-term relationships between business actors in an industry and the context in which the firm operates have the explanatory value when the model describes the internationalization of firms It is assumed in the model that the network, in which the firm is active, is the main driving force of the internationalization. All the actors in a network are interdependent and interact with each other in one way or another. This enables the firm to have a high degree of internationalization without a high degree of assets in a specific foreign market. A basic assumption in the model is that a firm is dependent on other firms’ resources within the network (Hansson, Sundell & Öhman, 2004). The Uppsala model has its theoretical base in the behavioral theory of the firm (Cyert & March, 1963; Aharoni, 1966). It is also influenced by Penrose´s theory of the growth of the firm (Penrose, 1995). The behavioral theory describes the internationalization of the firm as a process 4 in which the firm gradually increases its international involvement, and this is expressed in the Uppsala model through psychic distance and the establishment chain (Hansson, Sundell & Öhman, 2004). The process develops through the exchange between the development of knowledge about the foreign markets and operations, and an increasing commitment of resources to those markets (Johanson & Vahlne, 1990). The central issues of the model are how organizations learn and how their learning affects their investment behavior (Forsgren, 2002). Another important aspect of the Uppsala model is that it is a dynamic model, describing the internationalization of a firm as a process (Hansson, Sundell & Öhman, 2004) . Knowledge Management Strategy Zack (1999) defines knowledge management as “purposefully and systematically enhancing and exploiting the intellectual resources available to an organization, to increase the firm's value. To understand how the firm builds long-term value, the place to look is its competitive strategy. If knowledge management programs are to build lasting value, they must directly support the competitive strategy of the organization”. It is more important for a firm to find new and better ways to combine traditional resources rather than having unique resources, because it is harder to imitate tacit knowledge that is developed through experience and embedded in specific business activities and processes. If the company knows more than its competitors, it will have the opportunity to stay in the lead. Therefore, the firm should evaluate opportunities to develop and add to what it knows, while 5 easing the threat of trying to compete with less knowledge compared to its competitors (Zack, 1999). Resource-based View Resource-based theory treats firms as potential creators of value-added capabilities, and the underlying organizational competences involve viewing the assets and resources of the firm from a knowledge-based perspective (Prahalad and Hamel, 1990;). It focuses on the idea of costly-tocopy attributes of the firm as sources of business returns and the means to achieve superior performance and competitive advantage (Halawi, Aronson & McCarthy, 2005). A firm’s resources consist of all assets both tangible and intangible, human and nonhuman that are possessed or controlled by the firm and that permit it to devise and apply value-enhancing strategies (Barney,1991; Wernerfelt,1984). Resources and capabilities that are valuable, uncommon, poorly imitable and non-substitutable (Barney, 1991) comprise the firm’s unique or core competencies (Prahalad and Hamel, 1990) and therefore present a lasting competitive advantage. Intangible resources are more likely than tangible resources to generate competitive advantage. Especially, intangible firm-specific resources such as knowledge permit firms to add up value to incoming factors of production (Halawi, Aronson & McCarthy, 2005). Such advantage is developed over time and cannot easily be imitated. Barney (1991) regards resources as those controlled by a firm that allow the firm to formulate and implement strategies that expand its efficiency and effectiveness. According to his VRIO framework, resources like value creation for the customers, rarity compared to the competition, inimitability, and organization would present sustainable competitive advantage (Halawi, Aronson & McCarthy, 2005). 6 Figure 1: Internationalization Intent Model Mentality Filters Awareness Market Commitment Gap Knowledge Gap Level of Internationalization Intent Export International 7 Multinational Managerial Mentality Filter The top management team members can play a critical role in shaping firm-level responses to discontinuities like international markets (Kaplan, Murray and Henderson 2003) Managers encounter either success or failure, when they face environmental stimuli. Over the years, their experience evolves into a success model consisting of ‘things that work’ and ‘things that do not work’ and they use such models in their daily decision-making. However, these models are valid as long as the environment remains unchanged. As the environment undergoes a market change, managers’ historical success models become a major obstacle to firm’s adaptation to new reality (Ansoff, 1990) The most famous example of failure to recognize imminent discontinuity is Henry Ford’s rejection to admit the end of the single model automotive era. The manager filters the novel changes that are not relevant to his historical experience, and therefore ignores the shape of the new environment. Ansoff refers this as ‘mentality filter’. In international markets, managers face several challenges: The Cognitive Challenge The manager should be free of refusal, nostalgia and arrogance. He should have no emotional or intellectual investment in history or the future. He must be intensely conscious about what has changed in the market and how these changes are likely to shape the new market. (Ansoff, 1990; Hamel, 2003) 8 The Creative Challenge The manager should look for alternatives as well as awareness. He must create a set of new options as forceful alternatives to dying strategies. He should not only perceive the underlying trends that will make the future different from the past, but also make novel examinations of historical trends and create new strategies. (Ansoff, 1999; Hamel, 2003) Power Challenge Managers should not feel threatened with a discontinuity, try to minimize or refuse to recognize the impact of discontinuity to the firm. He must have the power to assure the acceptance of change. Recognizing the mentality of others makes an important contribution to the success of the firm. (Ansoff, 1999; Hamel, 2003) Entrepreneurial Challenge Managers should have vision of new future for the firm. Achieving this, he should be tolerant to failure. He should experiment a portfolio of new strategies, and a one-time failure should not deter the manager from trying again. (Ansoff, 1999; Hamel, 2003) Proposition1: Managerial mental challenges have a negative relationship with awareness of the international market. 9 AWARENESS After managerial mentality filter, the earliest possible response to new market environment should be awareness strategies. Firms gather their basic awareness through methods like economic forecasting, sales forecasting or competitive analysis, but these measures are most often extrapolative and do not provide information about strategic discontinuities. Starting the awareness activities does not require concrete information about threats and opportunities. (Ansoff, 1990) External Environmental Scanning Choo (1999) defines environmental scanning as “the acquisition and use of information about events, trends, and relationships in an organization's external environment, the knowledge of which would assist management in planning the organization's future course of action”. Its concentration is on the recognition of emerging issues, situations, and potential pitfalls that may influence an organization's future in the international market (Albright 2004). Environmental scanning works as an early warning system to identify potential threats and opportunities to the organization (Albright 2004). Managers can better identify external changes through environmental scanning. The information gathered help managers make strategic decisions about new resource needs and capability development efforts to address these changes (Kor, Mahoney and Pettus 2007). The process assumes that potential impacts on the organization may come from unpredictable and uncontrollable sources. Thus, environmental scanning is closely linked to strategic planning (Albright 2004). 10 Also, environmental scanning corresponds to a key process of organizational learning because organization's ability to adapt to international market depends on evaluating and understanding the external changes (Choo 1999). Devotion of time and concentration of external monitoring is required for external scanning as a planned learning activity (Winter 2000). It involves engagement of new routines for not only managers but also for whole organization to scan threats and opportunities in the international market in order to provide relevant information and insights to decision makers. The organization should habitually be alert to environmental changes and be efficient in distributing the vital external information among itself. Scanning as a collective learning activity can surpass the scanning as a sole managerial responsibility (Kor, Mahoney and Pettus 2007). Internal Scanning External scanning by itself is a not an enough condition for successful environmental adaptation. Systematic internal scanning is also required before firm while identifying changing trends within the international market (Kor, Mahoney and Pettus 2007). It is vital for the firms to analyze their internal strengths and weaknesses during the strategy-making process (Barney 1991). In order to compete effectively in the international markets, internal processes such as R&D, process improvements, and improvements in infrastructure should be redeveloped and focused on identifying current weaknesses that need renewal the resource and capability bundle. A firm will have a better chance of developing new resource configurations and market positions that capitalizes on its unique strengths, if it can identify and evaluate its knowledge bases and unique capabilities (Kor, Mahoney and Pettus 2007). 11 Other factors to look at in internal scanning are routines and flexibility. Routines can play a critical role in creating new resources and new capabilities (Grant1996). Routines allow the firm to create value by changing the resource base to create, integrate, recombine, and release resources (Eisenhardt and Martin 2000). They may also used by the firm to readjust its resource base to adapt to changing market conditions (Zahra and George 2002). They can enable the firm to maintain and renew its resource and capability bundles by creating new operating routines that result in better resource applications and services. Also organizational capability routines help the firm disregard the existing routines that are no longer valuable economically in the international market environment (Kor, Mahoney and Pettus 2007). International market environment requires that the firm unlearn some of the existing routines that obstruct growth and strategic adaptation, and be replaced by new routines. The organization needs to systematically and continuously learn, unlearn, and develop new operative routines that results in superior value and resource productivity. This systematic rebuilding through emergent or planned unlearning and learning efforts also enables the firm to become strategically flexible (Kor, Mahoney and Pettus 2007). Volberda (1998) suggests strategic flexibility when the organization confronts unfamiliar changes that have broad consequences and needs to respond quickly. The issues and difficulties relating to strategic flexibility are by definition unstructured and non-routine. The signals and feedback received from the international environment tend to be indirect and open to multiple interpretations. Because the organization usually has no exact experience and no routine answer 12 to deal with the changes, management may have to change its game plans, dismantle its current strategies, or apply new technologies. According to Pasmore (1994), flexibility is embedded in the organization’s awareness, anticipation and adaptability in attaining a competitive advantage under conditions of rapid change. Drucker (1980) implies that business should be flexible enough to cope with unanticipated threats and opportunities resulting from uncertain future and unstable environment. Johnson (1992) emphasizes that flexibility is crucial quality as well as responsiveness for organizational success. Volberda (1998) contends that the flexible firm encourages creativity, innovation, and speed while maintaining coordination, focus and control. Proposition2: Coherently intertwined external and internal scanning capabilities increase the firm’s ability to identify its specific needs for choosing the level of internationalization intent. Market Knowledge Gap The market knowledge concept consists of general knowledge and market-specific knowledge. The general knowledge concerns marketing methods and common characteristics of certain types of customers. Market-specific knowledge concerns characteristics of the specific national market expressed as: "…its business climate, cultural patterns, structure of the market system, and, most importantly, characteristics of the individual customer firms and their personnel.” (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977) 13 Entering foreign markets is a knowledge development process, and the entrant firm may realize a considerable market discrepancy, i.e. the firm identifies a gap between the knowledge possessed and the knowledge needed for accomplishing the foreign business venture. Based on its strategic knowledge and capabilities, the organization can identify extent to which it various categories of knowledge are in alignment with its strategic requirements. Firm’s knowledge base is more volatile in international markets due to the increase in size or variety of knowledge gap, so the firm should either align its strategy with its capabilities or acquire the capabilities to execute its strategy This knowledge gap also captures some of the notion of the liability of foreignness and requires that the new local operation learn how to operate successfully and to fill the knowledge gap in the local environment (Zaheer, 1995). Both internationalization process theory (Johanson and Vahlne, 1977; Erramilli, 1991) and organizational learning theory (March, 1999) suggest a perceived knowledge gap will stimulate managerial actions in order to close the knowledge gap. In terms of market entry, it has been argued that firms need to acquire new knowledge to fill the gap between their current capabilities and those needed to compete successfully in the new market. Resource Commitment Gap According to Johanson & Vahlne, the market commitment concept is composed of two factors: the amount of resources and the degree of commitment. The amount of resources is described as the size of the investment that may include marketing, organization, personnel, and other areas. The degree of commitment on the other hand becomes higher the more the resources are 14 integrated with other parts of the organization and when their value is derived from this integration (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977, in Johanson & Associates, 1994). Described in different words, the more difficult it is to find alternative uses for the resources in question and the more specialized these resources are to a market, the higher the degree of commitment is. The resource based view holds that as the degree of control increases, the firm’s chances of success increases because the firm is able to deploy key resources essential to success (Isobe, Makino and Montgomery 2000; Gatignon and Anderson 1988). These resources could be intangible properties such as brand equity and marketing knowledge (Arnold 2004) or tangible properties such as a patent or a process blueprint. Control over such properties allows a firm freedom to deploy resources flexibly thus enhancing its chances of success. Resource commitment describes the assets that cannot be redeployed to alternative use without loss of value (Bell, 1996; Kim and Hwang 1992; p. 3). Resources commitment is closely linked to control, as substantial financial and management commitment will increase control (Young et al., 1989). Doz and Prahalad (1981; p. 5-6) conceptualize control as "the influence that a head office has over subsidiaries concerning decisions that affect subsidiaries strategy" such as choice of technology; definition of product market; emphasis on different product lines, allocation of resources; expansion and diversification of the subsidiary operations; and a willingness to participate in a global network of product flows among subsidiaries. They also define resource commitment as technology, capital management, and access to markets (p. 5). 15 As well as the knowledge gap, the firm should identify a gap between the resources controlled and the resources needed for accomplishing the foreign business venture. In the context of emerging markets, resource control provides two key benefits. First, it safeguards key resources from leakage, such as patent theft. Second, it allows internal operational control essential to a firm’s success in emerging markets (Luo 2001). In addition a firm could control key complementary resources such as access to local distribution channels which can be important to its success in any country. Market knowledge and resource commitment have a mutually inclusive relationship. The firm’s resource commitment evolves in correspondence with the gradual narrowing of its knowledge gap. Also, the other way around, the firm’s knowledge gap narrows with the increase in its resource commitment. Hence, Proposition3a: the greater the entrant firm’s commitment of resources to the foreign market, the smaller is the knowledge gap. Proposition3b: the greater the entrant firm’s knowledge of the foreign market, the smaller is the resource commitment gap. 16 LEVELS OF INTERNATIONALIZATION INTENT Level of internationalization intent depends on the firm’s propensity to expand its cross-border activities in terms of the intensity (for example, level of export) and the scope (for example, number of countries to which the firm exports) of such activities. The firm can choose the level of its internationalization intent by comparing its market knowledge gap and resource commitment gap. Below, three strategies are proposed according to this comparison. Export When the firm’s market knowledge gap and resource commitment gap are both high, the most appropriate internationalization intent will be exporting. Exporting is the most traditional and well established form of operating in foreign markets. Exporting can be defined as the marketing of goods produced in one country into another. The firm can either sell through agents or use a local sales office. (Ansoff, 1990) The advantages of exporting are: manufacturing is home based thus, so it is less risky than overseas based; it gives an opportunity to "learn" overseas markets before investing in bricks and mortar, and it reduces the potential risks of operating overseas. The major problem of exporting is that of market knowledge. Control, or the lack of it, is a major problem which often results in strategy decisions being in the hands of others. 17 International When the firm’s market knowledge gap and resource commitment gap become moderate, the the firm can move into international status. At this stage, the firm follows a decentralization process in which activities are progressively distributed among the countries in which the firm does business. Some of the activities the firm possesses are local marketing, local production, local R&D, and local diversification. (Ansoff, 1990) International firms are not required to own only technical competitive advantages developed back the home market, but can uncover and incorporate new capabilities from abroad. Meaning that, the firm can enhance and leverage its existing capabilities through greater international presence. Most resource and capability building through enhanced international market scope must derive from access to new component knowledge. The firm can access strategic know-how as well as the complementary resources, but these have to do with improving in a particular market or market activity. The firm still lacks necessary knowledge and resources to compete globally (Tallman & Fladmoe-Lindquist, 2002). Multinational Multinational level of internationalization requires both low market know market knowledge gap and resource commitment gap. It involves an enlargement of the overall corporate perspective and introduction of new relationships among parts of the firm. Some of the firm activities involve global competition, global optimization of production, resources and R&D, global diversification and global portfolio management. (Ansoff, 1990) 18 According to the transnational model by Barlett and Ghoshal, the focus is on the firm rather than the industry. Globalization leads to integrating strategic demands for worldwide efficiency, local responsiveness and world-class technology across all markets. It also addresses the need for organizational structure that is capable of controlling this integration without losing the unique qualities of the firm (Tallman & Fladmoe-Lindquist, 2002). The firm at the multinational level is able to decentralize operational responsibilities in differentiated subsidiaries while supporting strong integration among all affiliates. It can spread new technical capabilities throughout the worldwide market, exploiting new assets while they are still unique. It can also take advantage of global flexibility, arbitrage possibilities and cost optimization via the integration of resources and knowledge base (Tallman & FladmoeLindquist, 2002). Strategic Alliances If the firm’s market knowledge gap is low but resource commitment gap is high, or market knowledge gap is high but resource commitment gap is low, the firm can choose strategic alliances with foreign partners to close its gap in the foreign markets. Strategic alliances can be appealing because of several factors. By joining forces in producing components, assembling models, and marketing products, the firm can realize cost savings not achievable within its own market. It can share distribution facilities and dealer networks in order to strengthen its access to the customers. The firm can also fill the gaps in technical expertise, knowledge of local markets and working relationships with key officials in the host country government (Thompson, Gamble & Strickland, 2004). 19 Figure 1. Internationalization Intent Level Grid High Strategic Alliances Export Market International Knowledge Gap Multinational Strategic Alliances Low Low Resource Commitment Gap 20 High CONCLUSION In this study, I contribute to theories governing internationalization, knowledge management and resource-based view in order to produce a theoretical model and a pragmatic road map for selecting the right strategic intent for foreign markets. Knowledge management and resourcebased approaches observe the internationalization process of firms from considerably different angles. While the knowledge management approach is mainly focusing on the company and its environment, the central point of the resource-based approach is the control of resources within the firm and its enhancement. Traditional theories describing the internationalization process of firms, like the Uppsala model state that firms first choose to enter nearby markets with low market commitment. Nevertheless, this is not applicable to all firms. As the firm increases its international commitment, it faces a greater uncertainty. Although acquiring knowledge about psychically distant markets or specific information involved in foreign activities is costly, it remains potentially uncertainty reducing. Consequently, the more accessible the knowledge of foreign market is, the lower the transaction cost of operating on it can be. This study suggests that firms can acquire knowledge about the foreign markets and assess its resources and capabilities by internal and external scanning before entering to the foreign markets. One important factor underlying the awareness of the firm is the managerial mental challenges that may affect the perception of reality. Coherently intertwined and unbiased 21 external and internal scanning capabilities increase the firm’s ability to identify its specific gaps for choosing the level of internationalization intent. There are two gaps the firm needs to consider during the selection of the level of internationalization intent. One is the market knowledge gap and the other in resource commitment gap. These two are mutually inclusive. The firm’s resource commitment evolves in correspondence with the gradual narrowing of its knowledge gap. According to the status of these gaps, the study suggests several strategies for competing in the foreign markets. Further empirical research is critical for helping determine the processes for eliminating the managerial mental challenges, filling knowledge gaps and resource commitment gaps and the factors influencing the international involvement. 22 REFERENCES Albright, K. S. (2004). Environmental Scanning: Radar for Success, Information Management Journal 38 (3): 38 Aharoni, Y. (1966). The Foreign Investment Decision Process. Boston: Harvard University, Graduate School of Business Administration, Division of Research. Ansoff, H. I. (1990). Implanting Strategic Management, Prentice Hall PTR. Bartlett, C.A., Ghosal, S. (1988). Organising for worldwide effectiveness: the transnational solution. California Management Review, Vol. 31 No.1, pp.54-75. Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management Studies, 17: 99-120. Buckley, P. J., & Ghauri, P. N. (1993). The Internationalization of the firm. London: Academic Press. Cavusgil, S.T. (1984). ‘ifferences among exporting firms based on their degree of internationalization, Journal of Business Research, 12(2): 195-208. Choo, C. W. (1999). The Art of Scanning the Environment. Bulletin of the American Society for Information Science 25 (3):13-19 Cyert, R., J. March. (1963). A Behavioral Theory of the Firm. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: PrenticeHall. De Clercq D., Sapienza H. J., Crijns H. (2005). The Internationalization of Small and MediumSized Firms: The Role of Organizational Learning Effort and Entrepreneurial Orientation. Small Business Economics 24 (4): 409-419. Drucker, P. (1980). Managing in turbulent times. London: Heinemann. Eisenhardt, K., J. Martin. (2000). Dynamic capabilities. Strategic Management Journal, 21: 1105-1121. Gjerding, A. N. (1999) The evolution of the flexible firm: New concepts and a Nordic comparison, National Innovation Systems, Industrial Dynamics and Innovation Policy Conference. Grant, R. M. (1996). Prospering in dynamically competitive environments: Organizational capability as knowledge integration. Organization Science, 7 (4): 375-387. 23 Halawi L., Aronson, J., and McCarthy, R. (2005). Resource-based view of knowledge management for competitive advantage. Journal of Knowledge Management, 3(2),pp. 75-86. Hamel, G. and Valikangas, L. (2003). The Quest for Resilience, Harvard Business Review 81(9): 52–63. Hansson, Gabrielle and Sundell, Hanna and Öhman, Marcus. (2004). The new modified Uppsala model. Högskolan Kristianstad/Institutionen för ekonomi. Johanson, J. and Vahlne J.-E. (1977). The Internationalization Process of the Firm - A Model of Knowledge Development and Increasing Foreign Market Commitments. Journal of International Business Studies, 8(1): 23-32. Johanson, J. and Vahlne, J.-E. (1990). The mechanism of internationalisation, International Marketing Review, 7(4): 11-24. Kor, Y. Y., Mahoney J. T., M. L. Pettus. (2007). A Theory of Change in Turbulent Environments: The Sequencing of Dynamic Capabilities Following Industry Deregulation” College of Business, Office of Research, Working Paper 07-0100: 1-43 Koornhof, C. (2001). Developing a framework for flexibility within organizations. S.Afr.J.Bus.Manage. 32(4): 21-30 Ling-Yee, L., 2004. An Examination of the foreign market knowledge of exporting firms based in the People’s Republic of China: Its determinants and effect on export intensity. Industrial Marketing Management 22, 561-572. Maheran, Nik, Muhammad, Nik, Muhammad, Zainuri The Strategic Planning Approach on Knowledge Accumulation in the Internationalization Process: A Proposed Model Universiti Teknologi Mara, Kelantan Pasmore, W. A. (1994). Creating strategic change: Designing the flexible, high performing organization. New York: Wiley. Penrose, E. T. (1995). Foreword in E. T. Penrose The Theory of the Growth of the Firm. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Peters, T. (1987). Thriving on Chaos: Handbook for a Management Revolution. London:McMillan Prahalad, C. K., and Hamel, G. (1990). The Core Competence of the Corporation. Harvard Business Review, Vol. 68, No. 3, pp. 79-91. S. Kaplan, F. Murray and R. Henderson (2003). Discontinuities and Senior Management: Assessing the Role of Recognition in Pharmaceutical Firm Response to Biotechnology. 24 Industrial & Corporate Change, 12 (4): 203-233. Tallman, S., Fladmoe-Lindquist, K. (2002). “Internationalization, Globalization, and CapabilityBased Strategy. California Management Review, 45(1), Fall 2002:116-135. Teece, D. J. (1982). Towards an economic theory of the multi-product firm. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 3: 39-63. Teece, D. J., G. Pisano. (1994) The dynamic capabilities of firms. Industrial and Corporate Change, 3 (3): 537-556. Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., A. Shuen. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18((7): 509-533. Thompson, A., Gamble, E. J. and Strickland, A. J. (2004) Strategy McGraw Hill. pp. 178-182. Volberda, H.W. (1998). Building the flexible firm: How to remain competitive. New York: Oxford University Press. Winter, S. G. (2000). The satisfying principle in capability learning. Strategic Management Journal, 21: 981-996. Welch, L.S and R.K. Luostarinen (1988), Internationalization: Evolution of a Concept. Journal of General Management. 14 (2) 36-64. Welch, D. E., Welch L. S., 1996. The internationalization process and Networks: A strategic Management Perspective. Journal of international marketing, 4 (3), 11-28. Wernerfelt, B. (1984). A Resource-Based View of the Firm. Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 5, pp. 171-180. Zack, M. (1999). Developing a Knowledge Strategy, California Management Review, 41 (3): 125-145. Zahra, Shaker, & George, Gerard. (2002). Absorptive capacity: A review, reconceptualization, and extension. Academy of Management Review, Vol. 27, No. 2, 185-203. 25