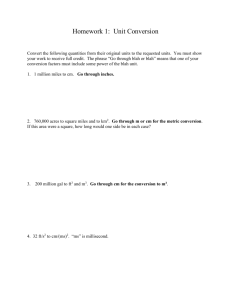

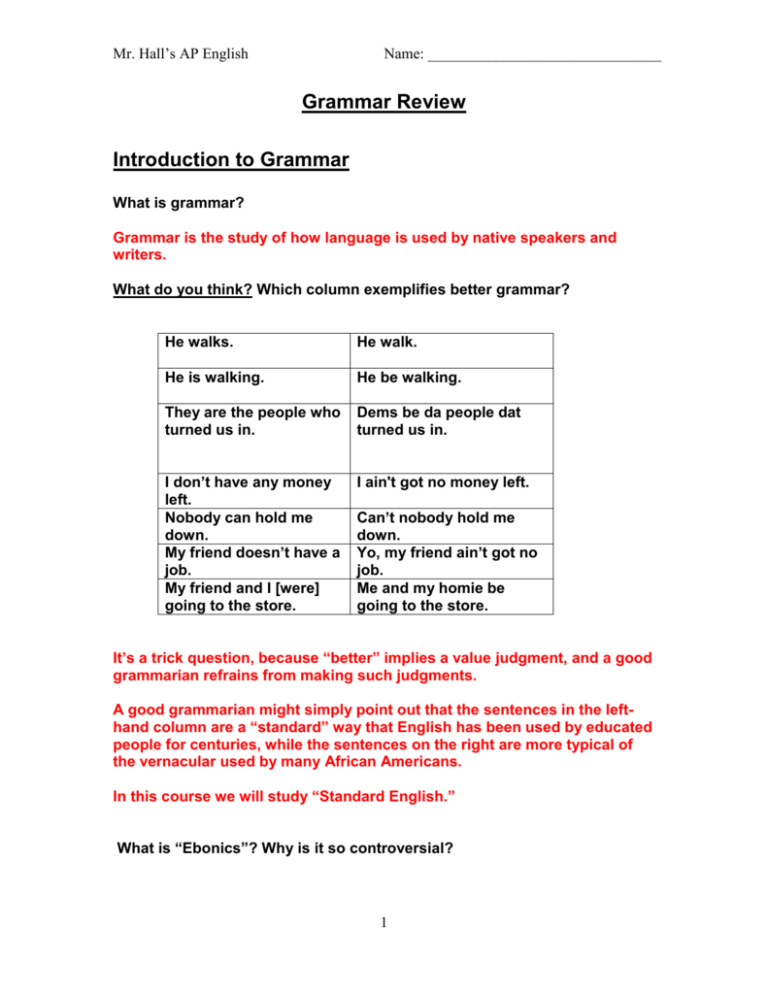

Mr. Hall's Grammar Review

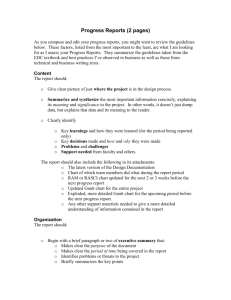

advertisement