Dissertation (20 000) - Action Research @ actionresearch.net

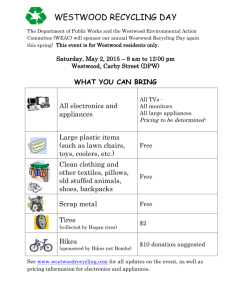

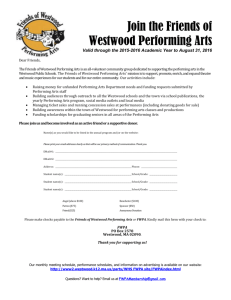

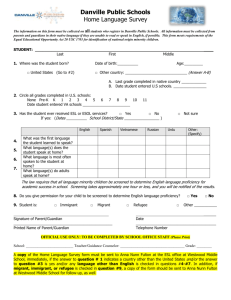

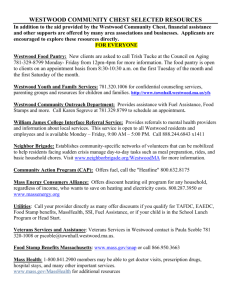

advertisement