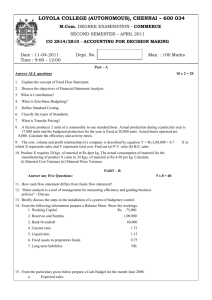

August 2014

advertisement