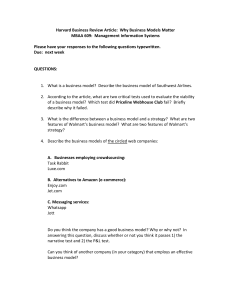

Chapter – IX

advertisement