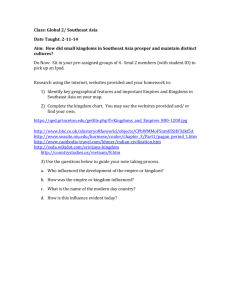

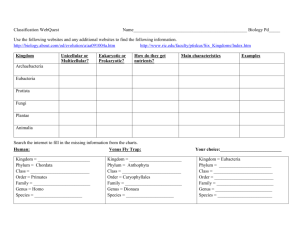

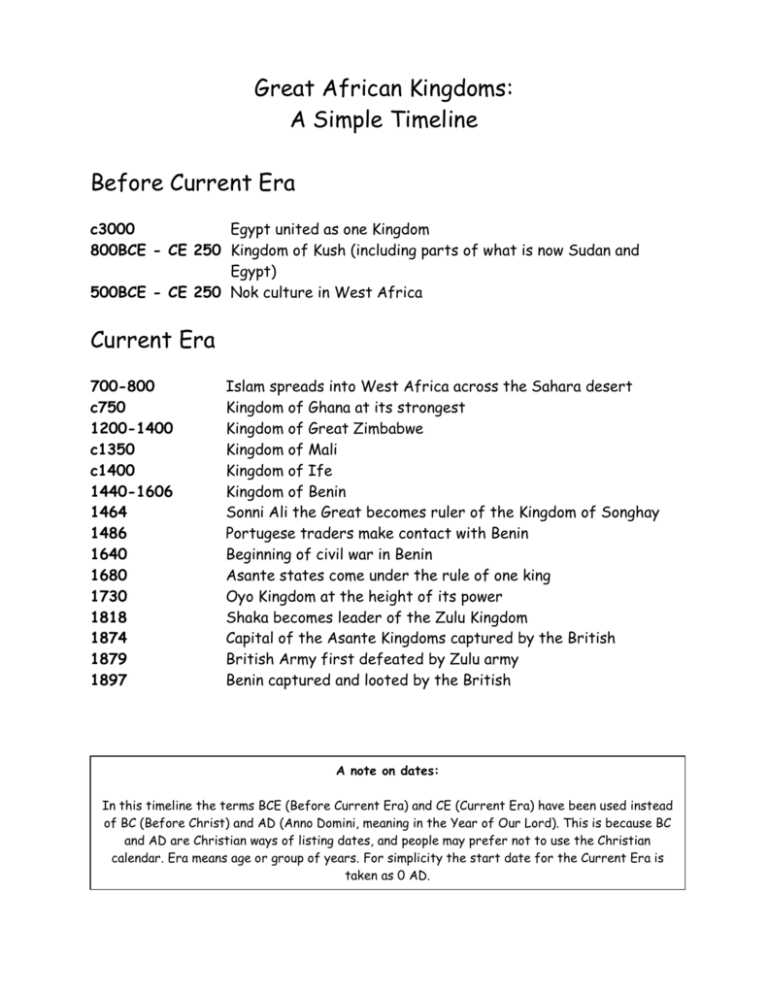

A basic timeline for The rise and fall of the Great African Kingdoms

advertisement

Great African Kingdoms: A Simple Timeline Before Current Era c3000 Egypt united as one Kingdom 800BCE - CE 250 Kingdom of Kush (including parts of what is now Sudan and Egypt) 500BCE - CE 250 Nok culture in West Africa Current Era 700-800 c750 1200-1400 c1350 c1400 1440-1606 1464 1486 1640 1680 1730 1818 1874 1879 1897 Islam spreads into West Africa across the Sahara desert Kingdom of Ghana at its strongest Kingdom of Great Zimbabwe Kingdom of Mali Kingdom of Ife Kingdom of Benin Sonni Ali the Great becomes ruler of the Kingdom of Songhay Portugese traders make contact with Benin Beginning of civil war in Benin Asante states come under the rule of one king Oyo Kingdom at the height of its power Shaka becomes leader of the Zulu Kingdom Capital of the Asante Kingdoms captured by the British British Army first defeated by Zulu army Benin captured and looted by the British A note on dates: In this timeline the terms BCE (Before Current Era) and CE (Current Era) have been used instead of BC (Before Christ) and AD (Anno Domini, meaning in the Year of Our Lord). This is because BC and AD are Christian ways of listing dates, and people may prefer not to use the Christian calendar. Era means age or group of years. For simplicity the start date for the Current Era is taken as 0 AD. Teacher’s Notes: This timeline only covers a small part of the history of a large and complex continent. Since the names of the Kingdoms and places cannot be found on contemporary maps, a good starting point would be to provide an old map of Africa (see pick n’ mix), for students to see where these highly advanced and successful Kingdoms were located. This can then lead onto discussions about the vast size of some of these Kingdoms and their territories, and what gave them coherence and strength. Teachers may also want students to choose a date, and compare and contrast what was happening at the time in different parts of Africa, with their own country and/or continent they live in. Finding Out More Yourself Teachers may want to refer to the briefing on ‘Africa before the Transatlantic Slave Trade’ to find out more about the contributions that Africa and Africans have made to world history. Teachers may want to read the briefings, and adapt them for groups of different ages and abilities. Structured Enquiry Task This timeline could be used to encourage students to question information for its accuracy and whether it is telling the full story or not. For example, do we learn that civilisations in Africa were developed to a higher degree than in Europe in the 14th or 15th centuries? In school textbooks all over the world, a limited amount of information about African history is given, in some countries less than others. Why might this be? What effect does it have on our ideas and perceptions of Africa and its importance in the world? The task and challenge for students is therefore to find out more! Teachers could set up a structured piece of research, which would be based on developing students’ knowledge and understanding, as well as research and presentation skills. Teachers could try to provide a range of resources, for example written and visual materials from the internet (see the ‘Links’ pages for this section) or from your local library. Some museums may have good and relevant collections and it may be valuable for teachers to organise a school trip. Oral history is also a very important way of telling stories about the past that might not be written down. If it is possible, why not invite an older person from your local community in to school, to tell students about some of the ancient Kingdoms of Africa, which existed thousands of years before the Europeans arrived. Teachers should look at some of the earliest inventions and discoveries made by peoples of ancient Africa, showing tangible examples where possible. Format: Clearly state what students are expected to produce as evidence of their research and learning. You could ask for: A piece of creative writing in the form of an essay or report. A short presentation to their class, for example using images, a white/chalk board, or if it is possible, a projector or Microsoft PowerPoint. Depending on the subject, teachers may want to ask students to dramatise their findings, making them into a sketch or a play. Students could visually depict one or more aspects of an ancient African Kingdom of their choice. Or they could make a replica of a traditional African artefact with an explanation of how and what it was used for. Almost all traditional African artefacts have strong and significant meanings, so it is important that whatever students make or design, are well researched. Timing: Students will need a clear, realistic deadline, and adequate time to do this task well. We recommend about two hours of class time, in addition to time spent researching in the school or local library, on the internet or using other forms of research. Tips: Tell local museums and libraries in advance to expect a visit from local school students. This allows them time to think about what resources they have available. They may also have a specialist on the subject who could do a short talk or answer questions that students have. It will take students some time to access good information, so be sure to set enough time aside, both during lessons and at home. Tell students that they need to be critical of the information they find and that they will need to edit and redraft it into their own style. Good researchers never copy chunks from books, and they always include a credit to acknowledge the original source. Debriefing At the end of the research project, provide an opportunity for students to share what they have learnt with each other, and see what others have done. Ensure that you tell students you will do this at the start of the project, because it can be a powerful motivator and help to raise confidence, expectations and achievement. Acknowledgement: This is based on an exercise devised by trainee History teachers at the Faculty of Education of The University of The West of England, Bristol and Dean Smart, their group tutor