Week 4 Reading Assignment - CLSS 231 Power, Image

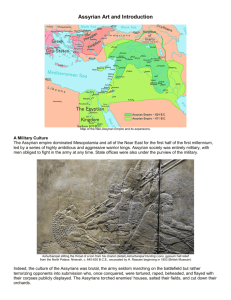

advertisement

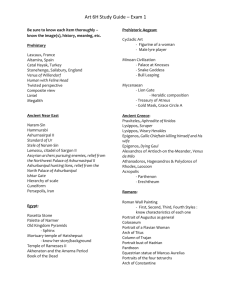

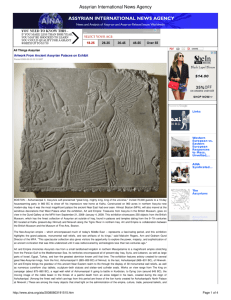

CLSS 231: POWER, IMAGE, & PROPAGANDA IN THE ANCIENT WORLD WEEK 4 (FEB 1 & 3): ASSYRIAN IMPERIAL ART, CA. 900 – 600 BC Reading: Selection of Neo-Assyrian imperial inscriptions, from M. Chavalas (ed.) Historical Inscriptions in Translation: Ancient Near East. Russell, J. 1991. “The Message of the Southwest Palace Reliefs,” in Sennacherib’s Palace without Rival at Nineveh, pp 251-262. Reed, S. 2007. "Blurring the edges: a reconsideration of the treatment of enemies in Ashurbanipal's reliefs." In Ancient Near Eastern Art in Context, edited by J. Cheng and M. H. Feldman, 101-17 (Illustrations pp 118-130). By Tuesday, take the time to look at the images I’ve posted on the website and read the selected inscriptions; both go in chronological order (see attached handout for a list of the different kings and their buildings and monuments). The inscriptions (each of which is preceded by an introduction by the translator that will give you the necessary background) are full of unfamiliar and sometimes incomprehensible names and places, but don’t worry about this; focus on the themes and ideology expressed therein. As you look at these images, take note of the following (and do give this some time; I’ve lightened the reading load in order to give you more time to just study the images): What themes are present in the reliefs? In what way(s) is the ideology of Assyrian kingship as presented in official texts reflected visually in Assyrian palace reliefs and other monuments? What artistic/pictorial conventions are used to communicate the narratives/themes/messages, and how do these techniques change from the reign of Ashurnasirpal (earliest) to Ashurbanipal (latest)? How much emphasis is there on landscape? What are possible explanations for this? Should the long narrative reliefs on the palace walls be regarded as “historical narrative”? Why or why not? Regarding the placement of inscriptions in/on/among the visual narrative; sometimes the writing is related directly related to the images/episodes on/around which it is written, but often it has nothing to do with those images explicitly. Why would they carve the text over the narrative scenes, instead of empty/unoccupied space (as in the stele of the vultures, where the writing occurs only in the blank space)? What does this say about the relationship between the art and the text? Why are there so many seemingly superfluous details in the visual narratives? How much individuality is there in the figures? What are we to make of the fact that Assyrian women are nearly completely absent from all of these reliefs? (Foreign captive women, however, are consistently depicted) Consider the hunt scenes of Ashurbanipal: he doesn’t disguise the fact that this is a very artificial hunt, i.e., not in the wild – lions are being released from the cages for the king to shoot. What is the significance of this? And what is the significance of the various depictions of the dying, bleeding, lions? What type of emotions/reaction do you think the artist/designer is trying to evoke? By Thursday, read the articles by Reed and Russell. The Reed article specifically addresses the complexity of the representation of enemies in Assyrian art. The selection from Russell’s book discusses the challenges in interpreting the motive and meaning of the relief sculpture of Sennacherib’s infamous palace. According to Russell what is the intended message of Sennacherib’s reliefs, and to whom is it directed? What evidence/logic does he base his assertions on? In what ways are foreigners represented in Assyrian art? How much variation is there? What attitudes are suggested by these representations? How plausible do you find the interpretations of Reed? There is an explicit/implicit assumption in much scholarship on Assyrian art that the depiction of the harsh treatment of enemies in Assyrian palace art was intended at least in part to deter subject peoples from rising up. To what extent is this plausible? Is this really a leading motivation for the presence of enemies in Assyrian art? Blog Assignment Week 4: Violence in Art Ever since the discovery of Assyrian palace reliefs in the 19th century, observers have been particularly struck by seemingly cavalier depictions of violence and brutality; some commentators have maintained that this is a reflection of the particularly brutal nature of Assyrian society and culture, and assume that their imperial reign must have been particularly harsh, as opposed to (for example) the Persians, whose empire has been regarded more favorably by historians. Not coincidentally, Persian imperial art is practically devoid of violence. (To be fair, these opinions are also shaped by the Old Testament portrayal of Assyrians as evil and the Persians as good, especially Cyrus the Great who allowed the Jews to return from exile.) But this begs the question: what does the employment of violence in art really say about a society? Can we use its presence (or lack of presence) as evidence about the level of violence in day-to-day life of that society, or in their dealings with foreign nations/peoples? How much does art truly mirror life? Relevant Kings of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, their conquests and the major buildings/monuments we’re looking at. Below you’ll find a very brief summary of each king’s activity and a list of the works of art from each king’s reign I’m having you look at. Ashurnasirpal II (ca. 883-859 BC) Ashurnasirpal II fought 14 campaigns in various directions, including Turkey, Iran, Syria-Palestine. He also founded the city of Calah (modern Nimrud) and built a huge palace there. Reliefs from the “Northwest Palace” at Calah/Nimrud, depicting military campaigns, royal rituals, and religious figures and rituals. Shalmaneser III (858-824 BC) Shalmaneser III was the son and successor of Ashurnasirpal II; he faced opposition in the Syro-Palestine region and confronted a coalition of states/city-states, including Damascus and Israel/Judah. Bronze gates from the city of Balawat; the “Black Obelisk” Both of these works of art come from the Assyrian homeland; in general, the surviving reliefs of Shalmaneser focus on tribute rather than Sargon (721-705) Sargon seems to have usurped power, although it appears that he is related to the ruling dynasty; brought more territory in the west under control, including central Anatolia and the kingdom of Judah; reasserted authority in Babylon; continued to assault Urartu, installing a puppet ruler. Sargon founded a new royal city on virgin soil: Dar Sharrukin/Khorsabad; it was abandoned after his unfortunate death in battle, which was taken as a bad omen. sculptural decoration from his palace at Khorsabad (not well preserved), most of which is in the Louvre Sennacherib (704-681 BC) Mainly engaged in frontier wars: Phrygia to west in Asia Minor; Urartu in the northern highlands; Elamites and Medes in Iran/Zagros mountains; Egypt; fought raiding nomadic communities of Cimmerians and the Scythians to North; appears not to have engaged in any sort of imperial expansion. Moved the capital back to the old and sacred city of Nineveh and began a huge building program, including a lavish palace and huge park, diverting a nearby river and constructing aqueducts to bring water into the city. reliefs from the Southwest Palace (Sennacherib called it the “palace without rival”), including: The siege of Lachish Quarry scenes Ashurbanipal (669-681 BC) Ashurbanipal is the last really strong ruler of the Assyrians; destroyed the city of Susa in Elam (Elamites frequently interfered in Babylonia). Built a new palace at Nineveh; relief sculpture of Ashurbanipal’s reign is the finest and most imaginative. Reliefs from Sennacherib’s palace added by Ashurbanipal (battle of Til-Tuba against the Elamites) reliefs from the North palace at Nineveh built by Ashurbanipal, including military, hunting, and banquet scenes.