CHAPTER 18

Economic Policy

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter, students should be able to do the following:

1.

Define the key terms at the end of the chapter

2.

Compare and contrast the laissez-faire, Keynesian, monetarist, and supply-side economic theories

and their positions on the role of government in the economy

3.

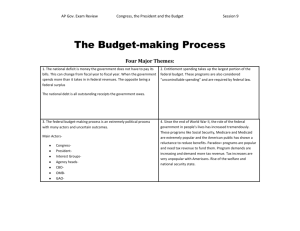

Outline the steps in the budget-making process

4.

Describe the various phases in budget reform since the 1970s

5.

List several possible objectives of tax policy

6.

Distinguish between progressive and regressive tax policies, and explain how both are present in

the United States

7.

Show how incremental and uncontrollable spending can limit the possibilities for cutting the

federal budget

8.

Assess the effectiveness of American taxing and spending policies in producing greater economic

equality

CHAPTER SYNOPSIS

Economic theory provides policymakers with simplifying assumptions that help them choose between

policies. The advice one economist gives is often contradicted by that of another economist. Both are

often contradicted by economic reality itselfan economic reality that is made all the more complex by

a global economy where the global flow of investment dollars affects worldwide employment patterns,

standards of living, and macroeconomic conditions like inflation and recession.

Several economic theories have an important role in explaining and shaping how today’s market

economies work. Laissez-faire economics advocates minimal government interference with the

operation of the free market. Laissez-faire policies, however, have been unsuccessful in solving the

problems associated with the business cycles in market economies. Keynesian theory holds that

government fiscal and monetary policies can smooth out these business cycles, thus preventing

economic depressions or raging inflation. Most democratic governments in the twentieth century have

used some Keynesian techniques. Monetarists question the political utility of Keynesian fiscal policies.

Fiscal spending to boost a depressed economy is generally untimely, and spending programs, once

started, can rarely be stopped again. The monetarists recommend that the economy be regulated through

monetary policies that are controlled by the politically independent board of governors (this is what we

see in the U.S. Federal Reserve System). Finally, supply-side economics represents the latest return to

traditional laissez-faire policies based on fewer government regulations and less taxation.

Policymakers rely on the budget as the tool by which decisions about policies are made. Since 1921, the

president has been responsible for drafting and submitting the budget to Congress. The actual

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

Chapter 18: Economic Policy

213

preparation of the budget is supervised by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). Since the

1970s, however, Congress has regained some control over the budget-making process by creating new

budget committees and the Congressional Budget Office. In passing of the Gramm-Rudman-Hollings

bill in 1985, Congress resorted to more drastic measures in order to reduce the exploding budget deficit.

As budget deficits were erased and surpluses began to accumulate, Congress had to determine how to

deal with this circumstance: should taxes be cut, or should social needs, like prescription drug coverage

for the elderly, be attended to? This is the classic controversy of American economic policy. Recent

events, especially the September 11 attacks, erased the surpluses and have brought both Congress and

the president back to the much more troubling question of how to close annual budget deficits.

Tax and spending policies are continually changing to meet the goals of policymakers. The sweeping

tax reform of 1986 represented a dramatic change in recent tax history. Americans remain relatively

apathetic about changing the broad contours of the present tax system, however.

Public concern over the national deficit has prompted politicians to attempt to reduce public

expenditures. Several factors militate against successful reductions in many programs. First,

incremental budgeting produces a sort of bureaucratic momentum that continually pushes federal

spending up. Second, most government spending cannot be reduced very easily because it is required

by existing laws that no politician in his or her right mind would attempt to modify. Third, Americans

have become accustomed to large domestic spending projects, but are reluctant to have their taxes

increased.

Despite massive government spending on social programs, the gap in income between rich and poor has

actually grown between 1966 and 2004. This highly unequal distribution of wealth has prompted some

critics to argue that spending and tax policies are dominated by pluralist politics, which favor wellfunded interest groups and the wealthy. They call for the introduction of majoritarian principles in

taxation and spending policies that would improve the distribution of income in society. Americans in

general are not willing to expand the use of progressive taxation policies, however—claiming to prefer

more regressive methods, such as a national sales tax or national lottery to increase receipts.

PARALLEL LECTURE 18.1

Economic Policy, Part 1

This lecture closely follows the discussion in the chapter. It covers theories of economic policies and

the budgeting process. The remaining topics are covered in Parallel Lecture 18.2.

I.

Theories of economic policy

A. Economic theories attempt to explain how market economies work.

B. Laissez-faire: absence of government interference with the laws of the market.

1. Operation of the free market is akin to process of natural selection

2. Adam Smith, Wealth of Nations: the “invisible hand” of the market justifies the belief

that the narrow pursuit of profits serves the broad interests of society.

C. Keynesian theory

1. Laissez-faire policies cannot do anything about economic depression or raging

inflation.

a) Economic depression: a period of high unemployment and business failures; a

severe, long-lasting downturn in the business cycle.

b) Inflation: an economic condition characterized by price increases linked to a

decrease in the value of the currency.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

214

Chapter 18: Economic Policy

2.

D.

Capitalist economies may suffer through many business cycles.

a) Business cycles: expansion and contractions of business activity, the first

accompanied by inflation and the second by unemployment.

b) United States has experienced more than fifteen business cycles in its history

3. Keynes’ proposition: business cycle fluctuations result from imbalances between

aggregate demand and productive capacity.

a) Aggregate demand: the money available to be spent on goods and services.

b) Productive capacity: the total value of goods and services that can be produced

when the economy works at full capacity.

c) Gross domestic product (GDP): the value of the goods and services actually

produced.

4. Keynesian theory: an economic theory that states that the government can stabilize

the economy—that is, can smooth business cycles—by controlling the level of

aggregate demand, and that the level of aggregate demand can be controlled by means

of fiscal and monetary policies.

a) Fiscal policies: economic policies that involve government spending and taxing.

(1) Government can increase demand by spending more itself or by cutting

taxes.

(2) When demand is too great, the government can spend less or raise taxes.

b) Monetary policies: economic policies that involve control of, and changes in,

the supply of money.

(1) Largely determined by the Federal Reserve Board

(2) Increasing the money supply increases aggregate demand and inflates

prices.

(3) Decreasing the money supply decreases aggregate demand and inflation.

5. Most capitalist economies have adopted Keynesian theory in some form.

a) Most countries have used the technique of deficit financing.

b) Deficit financing: the Keynesian technique of spending beyond government

income to combat an economic slump; its purpose is to inject extra money into

the economy to stimulate aggregate demand.

6. Council of Economic Advisers: a group that works within the executive branch to

provide advice on maintaining a stable economy.

a) Created by the Employment Act of 1946

b) Helps president prepare his annual economic report

Monetary policy

1. The political utility of Keynesian fiscal policies is limited.

a) Government spending generally takes too long to enact.

b) Spending often cannot be stopped once started.

2. Monetarists: those who argue that government can effectively control the

performance of an economy only by controlling the supply of money.

3. Federal Reserve System (the “Fed”): the system of banks that acts as the central bank

of the United States and controls major monetary policies.

a) Controls the money supply in three ways

(1) Selling and buying government securities (e.g., U.S. Treasury bonds)

(2) Changing the target for the federal funds rate (or, less frequently, the

discount rate)

(3) Changing its reserve requirement for banks

b) Historically, Fed has acted to combat inflation rather than stimulate economic

growth

c) The Fed is sufficiently independent of the president.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

Chapter 18: Economic Policy

President is not able to control monetary policy without the Fed’s

cooperation

(2) Fed’s activities are directly in the hands of its chairman

(3) Can create problems in coordinating economic policy

E. Supply-side economics

1. Supply-side economics: economic policies aimed at increasing the supply of goods

(as opposed to increasing demand), consisting mainly of tax cuts for possible investors

and less regulation of business.

a) Argues inflation can be lowered more effectively by increasing the supply of

goods

b) Favors tax cuts to stimulate investment and increase productivity

c) Ultimately produces more tax revenue

2. Reaganomics: inspired by supply-side economics

a) Reagan sought and got massive tax cuts in 1981.

b) Launched a program to deregulate business

c) Cut funding for some domestic programs

d) Acting contrary to supply side theory, substantially increased military spending

3. Effects of Reaganomics

a) Reduced inflation and unemployment

b) Worked as expected in industry deregulation

c) Failed to reduce the budget deficit

(1) 1981 tax cut was accompanied by huge drop in revenue

(2) Coupled with military spending, resulted in largest budget deficits ever

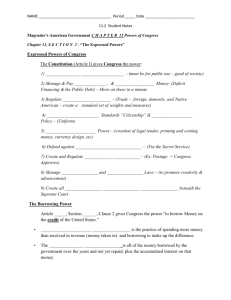

Public policy and the budget

A. Introduction to the budget

1. Control of the budget is important to members of Congress.

2. Congress has been unable to mount serious challenge to presidential budget authority

3. Since 1921, the president has been responsible for drafting the budget and submitting it

to Congress for approval.

B. The nature of the budget

1. Budget: the annual financial plan that the president is required to submit to Congress at

the start of each year.

2. The budget applies to the fiscal year: the twelve month period from October 1 to

September 30 used by the government for accounting purposes; a fiscal year budget is

named for the year in which it ends.

3. Budget authority: the amount government agencies are authorized to spend for their

programs.

4. Budget outlays: the amount that government agencies are expected to spend in the

fiscal year.

5. Receipts: for a government, the amount expected or obtained in taxes and other

revenue.

6. The difference between receipts and outlays is the budget deficit.

a) Government borrows on a massive scale to finance its operations when there is a

deficit.

b) Deficits limit the supply of loadable funds for business investment, and reduce

the economy’s growth rate.

7. Public debt: the accumulated sum of past government borrowing owed to lenders

outside the government.

a) National public debt in 2006: $4.8 trillion

b) More than 45 percent held by institutions or individuals in other countries

(1)

II.

215

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

216

Chapter 18: Economic Policy

C.

D.

Preparing the president’s budget

1. Preparation of the budget is supervised by the Office of Management and Budget

(OMB).

a) Office of Management and Budget (OMB): the budgeting arm of the Executive

Office; prepares the president’s budget.

b) During the spring, the OMB meets with the president to discuss the economic

situation and budgetary priorities.

c) By the summer, government agencies are ready to prepare budgets in agreement

with OMB guidelines.

d) During the fall, OMB analyzes agency requests and agencies negotiate for funds

and defend their own programs.

e) The budget is printed and presented to Congress by January 1.

2. The president’s budget is the starting point for Congress.

Passing the congressional budget

1. The traditional procedure: the committee structure

a) Types of committees involved in budgeting:

(1) Tax committees: the two committees of Congress responsible for raising

the revenue with which to run the government.

(a) House Ways and Means

(b) Senate Finance Committee

(2) Authorization committees: have jurisdiction over spending in a particular

area of responsibility.

(a) About twenty in the House, fifteen in the Senate

(b) Power has shifted from authorization committees to appropriations

committees

(3) Appropriations committees: decide which of the programs passed by the

authorization committees will actually be funded.

2. The traditional committee structure does not allow Congress as a whole sufficient

control over the budget process.

a) Authorization/appropriation structure is complex and offers interest groups too

many opportunities to impact on the budget

b) No single group responsible for the budget as a whole

3. Reforms of the 1970s: the budget committee structure

a) Budget committees: one committee in each house that supervises a

comprehensive budget review process.

b) Congressional Budget Office (CBO): the budgeting arm of Congress, which

presents alternative budgets to those prepared by the president’s OMB.

c) Heart of the 1974 reforms: timetable for congressional budgeting process

(1) Congress structured the budget as a whole according to the timetable they

had set.

(2) Process broke down during the Reagan years

4. Lessons of the 1980s: Gramm-Rudman

a) Gramm-Rudman: popular name for an act passed by Congress in 1985 that, in

its original form, sought to lower the national deficit be lowered to a specified

level each year, culminating in a balanced budget in FY1991; new reforms and

deficit targets were agreed on in 1990.

(1) If Congress did not meet deficit targets, across-the-board cuts would be

automatically triggered.

(2) In 1986, across-the-board cuts were triggered.

(3) In 1987, Congress and the president changed the law to match the deficit.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

Chapter 18: Economic Policy

5.

6.

217

b) Demonstrated that Congress lacked will to force itself to balance the budget

Reforms of the 1990s: balanced budget

a) Budget Enforcement Act (BEA): A 1990 law that distinguished between

mandatory and discretionary spending.

(1) Mandatory spending: expenditures required by previous commitments.

(a) Entitlements: benefits to which every eligible person has a legal right

and that the government cannot deny.

(b) Pay-as-you-go: the requirement that any tax cut or expansion of an

entitlement program must be offset by a tax increase or other savings.

(2) Discretionary spending: authorized expenditures from annual

appropriations.

(3) Law imposed caps (limits) on discretionary spending

b) Clinton’s 1993 budget deal made even more progress reducing the deficit.

c) The Balanced Budget Act (BBA): a 1997 law that promised to balance the

budget by 2003.

Backsliding in the 2000s: deficits return

a) Congress resented restrictions on freedom to make fiscal decisions

(1) Caps on discretionary spending and pay-as-you-go requirements expired at

the end of 2002.

(2) Government has run deficits since 2002.

b) Economy has slowed and projected surpluses have dwindled.

PARALLEL LECTURE 18.2

Economic Policy Part 2

This lecture picks up at the conclusion of Parallel Lecture 18.1. It covers tax policies and spending

policies and the way the two affect economic equality.

I.

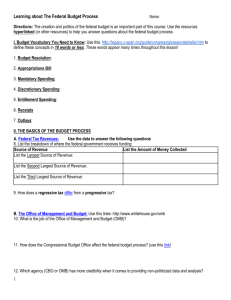

Tax policies

A. Revenue side of the budget

1. Designed to provide a continuous flow of revenue without requiring new annual

legislation

2. Tax policy may be used to accomplish many objectives.

a) Adjust overall revenue to meet budget outlays

b) Make the tax burden more equitable

c) Help control the economy

d) Advance social goals

e) Favor certain industries

3. Major sources of revenue (FY 2007)

a) Individual income taxes (45%)

b) Social security payments (37%)

c) Corporate income taxes (11%)

B. Tax reform

1. The Tax Reform Act of 1986

a) One of the more sweeping changes in tax history

b) Reclaimed revenue by eliminating tax deductions for corporations and wealthy

citizens

c) Revenue was supposed to pay for reduction in tax rates.

(1) Eliminated many tax brackets

(2) Approached the idea of a flat tax

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

218

Chapter 18: Economic Policy

(3)

II.

Flat tax violates principle of progressive taxation: a system of taxation

whereby the rich pay proportionately higher taxes than the poor; used by

governments to redistribute wealth and thus promote equality.

(a) 1985 tax code included fourteen tax brackets, ranging from 11 to 50

percent

(b) TRA 1986 law left only two brackets: 15 and 28 percent

(c) George H.W. Bush added a 3rd bracket (31%)

(d) Bill Clinton added a 4th (40%)

2. Changes to law in 2001 (and amended in 2003)

a) Increased number of tax brackets, changed income levels

b) Reduced revenue, resulted in deficits

c) Deficits exacerbated by downturn in the economy, increased need for homeland

security

C. Comparing tax burdens

1. Comparing the tax burden over time in the United States

a) Tax burden has not grown since the 1970s

b) Middle income families pay about 20 percent of income in federal taxes, about 10

percent in state and local taxes.

c) Largest increases have been in social security taxes

2. Comparing tax burdens in different countries

a) Americans think they pay more taxes than western Europeans—but they do not.

b) Almost every other democratic nation taxes more heavily than the United States.

c) Other nations provide more generous social benefits.

Spending policies

A. The FY 2007 budget accounted for $2.8 trillion in proposed outlays. (See text Figure 18.2.)

1. Social security ($586 billion, 22%)

2. Defense ($466 billion)

3. Medicare ($394 billion)

4. Income security ($367 billion)

5. Health ($276 billion)

6. Interest on the federal debt ($243 billion; 9%)

B. Federal spending over time (See Figure 18.3.)

1. Increases in defense spending reflects national involvement in conflicts (WWII,

Vietnam, the Cold War, September 11 attack).

2. Defense expenses fell during times of peace (after WWII, after the fall of

communism).

3. Government payments to individuals consumed less of the budget than defense until

1971.

4. Net interest payments increased substantially during years of budget deficits.

5. National spending has far outstripped inflation.

C. Incremental budgeting…

1. Incremental budgeting: a method of budget making that involves adding new funds

(an increment) onto the amount previously budgeted (in last year’s budget).

a) Members of Congress pay more attention to the size of the increment than to the

total size of the agency’s budget.

b) Produces a sort of bureaucratic momentum that continually pushes up spending

c) Earmark: government funds appropriated to be spent for a specific project.

2. … and uncontrollable spending

a) Certain spending programs cannot be reduced because they are enacted into

existing law.

(1) Uncontrollable outlay: a payment that government must make by law.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

Chapter 18: Economic Policy

(2)

219

FY 2007: almost two-thirds of budget outlays were uncontrollable or

relatively uncontrollable

b) Modifying existing laws and entitlements to reduce spending is politically

unpalatable.

c) Most Americans wish to increase or maintain current levels of spending.

III. Taxing, spending, and economic equality

A. Economic equality requires economic freedom to be compromised through redistribution of

wealth.

1. One means of government redistribution: tax policy, especially the progressive income

tax

2. Another means: government spending through welfare programs

3. Goal is not to produce equality of outcome, but reduce inequalities

4. Sixteenth Amendment gave government power to levy tax on individual incomes

B. Government effects on economic equality

1. Transfer payments: a payment by government to an individual, mainly through social

security or unemployment insurance.

a) Transfer payments do not always go to the poor (e.g., farm subsidies).

b) Transfer payments have had a definite effect on reducing income inequality.

2. Progressivity of national income tax rates has varied over time.

3. Combination of national, state, and local tax policies may violate progressivity

a) National payroll tax (funding social security and Medicare) is highly regressive

b) Most state and local sales taxes are also regressive.

c) Tax policies at all levels have historically favored those who draw from capital

rather than labor.

C. Effects of taxing and spending policies over time

1. Between 1966 and 2004, the gap in income between rich and poor grew. (See Figure

18.6.)

a) True despite the fact that many households in the lowest category have one-third

more earners

b) Average American worked ninety-three hours per year more in 2000 than in 1989

2. United States has most unequal distribution of income in comparative study of

eighteen developed countries

D. Democracy and equality

1. Distribution of wealth is highly unequal

a) Wealthiest 1 percent of American families control 33 percent of nation’s

household wealth (property, stock, bank accounts)

b) Distribution among ethnic groups is also highly unequal.

2. Why don’t “the people” share more equally in the nation’s wealth?

a) Interest group activity distorts government efforts to promote equality.

b) Majoritarian approach would not necessarily be redistributive.

(1) Little support for increasing income tax

(2) Public favors national sales tax (a flat tax)

(3) Public also supports a national lottery (also regressive)

3. Most Americans do not understand the inequalities of the national tax system.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

220

Chapter 18: Economic Policy

INTERACTIVE MEDIA LECTURE 18.1 WALL STREET

“Greed is Good”

Wall Street, Oliver Stone’s classic film about the go-go stock market of the 1980s, highlights the

relationship between American capitalism and the culture that surrounds it. In its most famous scene,

Wall Street mogul Gordon Gecko (Michael Douglas) explains to the stockholders of fictional Teldar

Industries that “Greed is good,” justifying this position in historical and practical terms, and applying it

to both industry and government alike.

Show the scene from the Teldar stockholders meeting (DVD Chapter 12, “Greed is Good,” video clip

beginning at 1:14:45 and running to 1:19:00). Use this clip to stimulate the discussion outlined below.

I.

Review: theories of economic policy

A. Laissez-faire

B. Keynesian

C. Monetarist

D. Supply-side

II. Discussion: Gordon Gecko’s theory of economic policy

A. What (if any) aspects of each of these theories are present in Gecko’s speech?

B. What other economic principles does Gecko articulate?

III. Discussion: government as a “corporation”

A. In what ways are corporations and government similar?

B. How have business principles influenced government? (Review information on the

“reinvention” movement in Chapter 13.)

C. How do government’s “other” purposes—freedom, order, and equality—keep it from

following through with good business principles?

IV. Can the “greed is good” approach fix government?

A. How might a “greed is good” approach change the government budgeting process?

1. How would this be advantageous?

2. How would it be problematic?

B. How might a “greed is good” approach change the tax structure?

1. How might this be advantageous?

2. How would it be problematic?

FOCUS LECTURE 18.1: AN INTERACTIVE LECTURE

Your Students, Taxation, and Public Spending

The purpose of this interactive lecture is to involve your students in a discussion of their own tax

burdens and public benefits. They will also explore the tax burdens and public benefits of others, at

least in a theoretical sense. They should be forewarned to read the entire chapter before coming to class,

and they should bring their textbooks to class in order to fully participate in the interactive lecture.

I.

Ask students to jot down for reference a list of all the taxes they pay to federal, state, or local

governments.

A. Ask for volunteers to read their lists.

1. Use this opportunity to point out taxes they may be unaware of: for example, if they

are mostly young renters, they may be unaware of property tax. If they are wealthier

students, they may be unaware of how their parents manage money that is in their

name and the taxes paid on it (such as capital gains).

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

Chapter 18: Economic Policy

221

Use this opportunity to point out “hidden” taxes, such as public college or university

fees that go back to state coffers; the gasoline tax, which is added into the gasoline

pump price; sin taxes; and others.

B. Ask students to “guesstimate” the proportion of taxes they pay relative to their earnings. If

you have data on actual proportions for taxpayers at the students’ income levels, share this

data with them.

C. Discuss with students the regressive and/or progressive nature of the taxes they mentioned.

Ask them to define each tax on their list according to these categories, and then ask their

opinions on the advantages or disadvantages of each type of tax.

II. Ask students to jot down the public services they receive. If students believe they are too middleclass to be getting much from government, be sure to remind them about public education

(including perhaps the college or university where they are taking this class), public roads,

airports, bridges, and others.

A. Ask for volunteers to read their lists.

1. Use this opportunity to discuss the positive and negative aspects of various government

programs that students actually use.

2. Use this opportunity to ask students to “guesstimate” what those services would cost if

they had to pay user fees each time they drove a highway, attended a class, etc. Try to

bring in data on actual costs of public instruction versus fees for students. (In most

states, student fees are considerably less than the actual costs.)

3. Ask students to evaluate the relationship between the taxes they pay and the services

they receive. Are they totally out of proportion? Are they evenly matched? What

alternatives might students propose?

III. Ask students their views about possible changes in the tax structure.

A. Given the current situation of taxation and public service, what tax changes might be

considered?

1. Students may bring up value-added taxes, sales taxes on services, or other forms of

taxation. If not, help them remember their reading.

2. Ask students to evaluate the federal income tax rates. Should they return to pre-Reagan

levels? What advantages or disadvantages might this have?

IV. Help students evaluate the taxation in other nations by using Compared with What?

A. Students should look at the bar graph in this feature and comment on the tax structures of the

other nations.

1. Are any students from another country? If so,

a) What tax structure does their nation use?

b) What public services does their country provide that the United States leaves to

the private sector?

2. How do the students perceive their U.S. taxes after seeing the comparisons?

V. Close your interactive lecture by asking students for feedback. Have each student jot down three

new items he or she learned during the lecture, and ask them to hand in these notes as they leave

the class. You can then get a sense of what they got from the process.

2.

PROJECTS, ACTIVITIES, AND SMALL-GROUP ACTIVITIES

1.

Politicians hailed the tax reform package passed by Congress in 1986 as the most significant

change in tax policy in recent history. Since that time income tax legislation has been altered three

timesby Presidents Bush, Sr., Clinton, and Bush, Jr. Every reform of the tax structure is hailed

by its defenders as being more “fair,” yet there are always others who argue that further tax

reform is necessary. This chapter provided the outline of some of the main types of tax reform

proposals. Little, however, is known about the long-term effects of these proposals on the

economy. Have students consult the Congressional Quarterly, the New York Times, the Wall

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

222

Chapter 18: Economic Policy

Street Journal, or some other source for analyses of tax reform plans as they are published when

they are passed, to learn some of their specific proposals as they relate to personal income,

industry, and investment. What predictions were right? What predictions didn’t come to pass?

What problems does each round of tax reform seek to fix, and what new ones does it create?

2.

In this chapter, the concept of incremental budgeting was introduced to explain the process by

which government agencies determine their budgetary needs. You can illustrate the dynamics of

incremental budgeting by setting up a simplified simulation of the congressional budget-making

process. Create nine to twelve separate government agencies and three to four congressional

committees for the simulation. Assign dollar figures for each agency for the current fiscal year,

the total budgetary outlays in the current fiscal year, and the projected budget target for the next

fiscal year. (The numbers do not have to correspond to real budgetary allocations, but the real

figures can be easily obtained from copies of the FY 2001 budget online.) Have each agency bid

to the appropriate committee for funds in the next budget. Students in the appropriate committees

should decide how much money will be allocated for each agency under their jurisdiction. After

this process is completed, tally the total budgetary requests from the committees. Was the overall

budget target exceeded? Discuss the implications of the simulation with your students.

3.

Pluralist politics have traditionally dominated the budgeting process. Students may be interested

in finding out how individual states go about getting money from the federal government. Invite a

state representative or one of his or her aides to discuss the strategies and techniques available for

this purpose. Have students discuss whether influential politicians (committee chairs, for example)

should be allowed to get more money from the federal government than do other senators. Have

students determine what political factors determine federal budget allocations to the states.

4.

Have students form small groups to discuss budget issues. They can begin by comparing their

personal budgeting styles with one another. How many students make written budgets? How

many are always in debt? How many always keep some savings in reserve? After students spend

about five minutes exploring this issue at the personal level, have them answer the following

questions: In what ways is the federal government like a family or individual when it creates a

budget? In what ways is the government quite different from a family or individual? According to

the text, what priorities are reflected in recent budgets? Who benefits most from the current

federal tax code and budget? Who suffers or is disadvantaged by the current system? How are the

students affected by our national priorities? What changes would they make if they were in

Congress? Give groups notice after their first segment (five minutes on the personal budget

comparisons) and give them about fifteen minutes with the larger discussion topic. Then

reconvene the class and find out what the groups concluded.

5.

Students can form small groups to discuss the following: What public or government programs do

they participate in (federal, state, or local)? Make sure they brainstorm and include everything

from public education to public highways. What taxes do they pay? (Again, have them consider

federal, state, and local taxes.) Ask students to evaluate the relationship between the public

services they receive and the tax dollars they contribute. Are they getting adequate services for

their contributions? If not, why not? What factors might contribute to a widespread sense that

taxes are too high, yet government doesn’t do its job well? Reconvene the class after about fifteen

minutes and ask for feedback from the groups. If you wish, prepare yourself in advance with some

current data for your area on rates for sales taxes, state income taxes, and property taxes. Be sure

to bring in the most recent federal tax booklet (Form 1042), which usually has a pie chart of tax

revenues and expenditures. Your data can be used to enhance the students’ discussion.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

Chapter 18: Economic Policy

223

INTERNET RESOURCES

Federal Reserve Board www.federalreserve.gov/

Learn about the structure and functions of “the Fed,” and get updates on economic conditions in

the United States.

Office of Management and Budget www.whitehouse.gov/omb

Get the most recent versions of the federal budget. View data, graphs, and text.

Congressional Budget Office www.cbo.gov/

View data, graphs, and text that present an alternative view of the federal budget.

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities www.cbpp.org

Conducts research and analysis on proposed budget and tax policies

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.