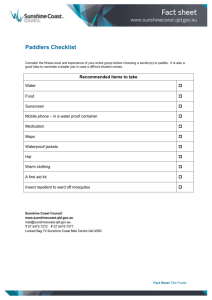

Section 1, Sea kayaking equipment

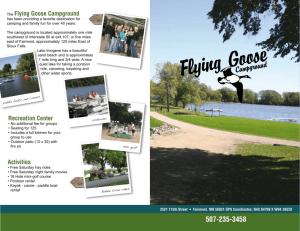

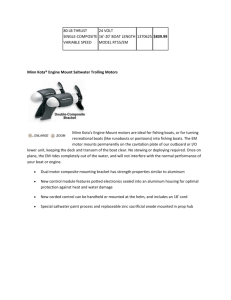

advertisement