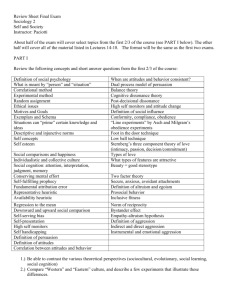

Chapter 18

advertisement

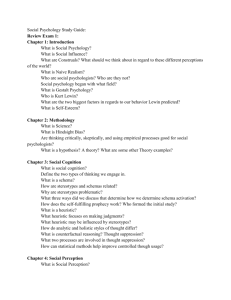

Chapter 18: Social Psychology Social Thinking Social psychology is the study of how people think about, influence, and relate to one another. Attributing Behavior to Persons or to Situations We generally explain people’s behavior by attributing it either to internal dispositions or to external situations. In accounting for others’ actions, we often underestimate the influence of the situation, thus committing the fundamental attribution error. When we explain our own behavior, however, we more often point to the situation and not to ourselves. Attitudes and Actions Attitudes predict behavior only under certain conditions, as when other influences are minimized, when the attitude is specific to the behavior, and when people are aware of their attitudes. Studies of the foot-in-the-door phenomenon and of role playing reveal that our actions can also modify our attitudes, especially when we feel responsible for those actions. Cognitive dissonance theorists explain that behavior shapes attitudes because people feel discomfort when their actions go against their feelings and beliefs; they reduce the discomfort by bringing their attitudes more into line with what they have done. Conformity and Obedience As suggestibility studies demonstrate, when we are unsure about our judgments, we are likely to adjust them toward the group standard. Solomon Asch found that under certain conditions people will conform to a group’s judgment even when it is clearly incorrect. We may conform either to gain social approval (normative social influence) or because we welcome the information that others provide (informational social influence). In Stanley Milgram’s famous experiments, people torn between obeying an experimenter and responding to another’s pleas to stop the shocks usually chose to obey orders, even though obedience supposedly meant harming the other person. Social influence is potent. Group Influence Experiments on social facilitation reveal that the presence of either observers or co-actors can arouse individuals, boosting their performance on easy tasks but hindering it on difficult ones. When people pool their efforts toward a group goal, social loafing may occur as some individuals take a free ride on others’ efforts. When a group experience arouses people and makes them anonymous, they may become less self-aware and self-restrained, a psychological state known as deindividuation. Within groups, discussions among like-minded members often produce group polarization, an enhancement of the group’s prevailing attitudes. This is one cause of groupthink, the tendency for harmony-seeking groups to make unrealistic decisions after suppressing dissenting information. The power of the group is great, but so is the power of the person. Even a small minority sometimes sways a group, especially when the minority expresses its views consistently. Social Relations Prejudice Prejudice often arises as those who enjoy social and economic superiority attempt to justify the status quo. Even the temporary assignment of people to groups can cause an ingroup bias. Once established, the inertia of social influence often helps maintain prejudice. Prejudice may also focus the anger caused by frustration on a scapegoat. Newer research reveals how our ways of processing information—for example, by overestimating similarities when we categorize people or by noticing and remembering vivid cases—work to create stereotypes. In addition, favored social groups often rationalize their higher status with the just-world phenomenon. Aggression Aggressive behavior, like all behavior, is a product of nature and nurture. Although psychologists dismiss the idea that aggression is instinctual, aggressiveness is genetically influenced. Moreover, certain areas of the brain, when stimulated, activate or inhibit aggression, and these neural areas are biochemically influenced. A variety of psychological factors also fuel aggression’s fire. Aversive events heighten people’s hostility. Such stimuli are especially likely to trigger aggression in those rewarded for their own aggression, those who have learned aggression from role models, and those who have been influenced by media violence. Enacting violence in video games also heightens aggressive behavior. Conflict Conflicts between individuals and cultures often arise from malignant social processes. These include social traps, in which each party, by protecting and pursuing its self-interest, create an outcome that no one wants. The spiral of conflict also feeds and is fed by distorted mirror-image perceptions, in which each party views itself as moral and the other as untrustworthy and evil-intentioned. Attraction Three factors affect our liking for one another. Proximity—geographical nearness—is conducive to attraction, partly because mere exposure to novel stimuli enhances liking. Physical attractiveness influences social opportunities and the way one is perceived. As acquaintanceship moves toward friendship, similarity of attitudes and interests greatly increases liking. We can view passionate love as an aroused state that we cognitively label as love. The strong affection of companionate love, which often emerges as a relationship matures, is enhanced by an equitable relationship and by intimate self-disclosure. Altruism In response to incidents where bystanders did not intervene in emergencies, social psychologists undertook experiments that revealed a bystander effect: Any given bystander is less likely to help if others are present. The bystander effect is especially apparent in situations where the presence of others inhibits one’s noticing the event, interpreting it as an emergency, or assuming responsibility for offering help. Many factors, including mood, also influence one’s willingness to help someone in distress. Social exchange theory proposes that our social behaviors—even our helpful acts— maximize our benefits (which may include our own good feelings) and minimize our costs. Our desire to help is also affected by social norms, which prescribe reciprocating the help we have received and being socially responsible toward those in need. Peacemaking Enemies sometimes become friends, especially when the circumstances favor cooperation to achieve superordinate goals, understanding through communication, and reciprocated conciliatory gestures.