Gresham Lecture, Tuesday 29 March 2011

What is this thing called “love”?

Professor Glenn Wilson

According to the Wise Old Owl in Disney’s Bambi:

Nearly everybody gets twitterpated in the springtime. … You’re walking along minding your own business. You’re

looking neither to the left nor to the right, when all of a sudden you run smack into a pretty face. You begin to get

weak in the knees. Your head’s in a whirl. And then you feel light as a feather, and before you know it you’re walking

on air. And then you know what? You’re knocked for a loop and you completely lose your head.

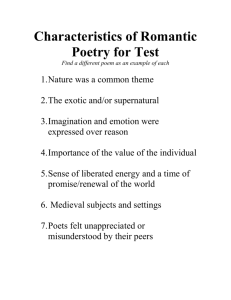

This description of falling madly in love will ring a bell with most of us. Romantic love is a distinct and

striking emotion with the capacity to “exhilarate, arouse and disturb”. It occurs in virtually every culture

and so may be considered a “human universal – or near universal” (Jankowiak & Fischer, 1992). Love is not

always seen as connected with marriage as in the Hollywood model; they do not necessarily “go together

like a horse and carriage”. In many societies, especially those favouring arranged marriage, love is more

likely to be viewed with suspicion, as an irrational, disruptive force. Some sceptics have defined love as

“the excuse used for moving from one relationship to another. However, the phenomenon of romantic love

itself is recognised in most times and places (Wilson & McLaughlin, 2001).

People describing themselves as being “in love” display a familiar pattern of emotions and behaviours.

There is increased energy, elation, pounding heart, sweaty palms, sleeplessness, loss of appetite, mood

swings, preoccupation with the loved one, and changes in habits to impress or maintain contact with them.

These behaviours are experienced as beyond rational control. There is a strong sexual desire for the loved

one but this is superseded by the need for emotional and physical contact. There may be intense, possessive

jealousy and a strong separation anxiety. Loss of the loved one is felt as catastrophic. Fisher et al (2005) note

that love is a stronger motive than sex because few people commit suicide because of sexual frustration.

The development of passionate love has been studied experimentally. Some degree of love can be

generated by having a pair of strangers gaze into each other’s eyes and exchange intimate details about

themselves (Kellerman et al, 1989). Add soft lights, music, and a glass of wine, and this is pretty much what

goes on in a singles bar or on a date. Low light causes the pupils of the eyes to dilate, and since strong

emotions have the same effect, this can be read (misattributed?) as interest in the other person, thus setting

up a spiral of mutual attraction.

Any kind of powerful emotion, however induced (even by direct injection of adrenalin) can facilitate love

(Walster & Berscheid, 1971). The emotional stimulation does not even have to be positive. Feelings of fear,

aroused by crossing a dangerous swing bridge, have been shown to promote sexual excitement and the

1|Page

desire for attachment (as compared with subjects who have crossed a solid bridge). This discovery led

some dating agencies to offer “adrenaline dates”, whereby the courting couple spend an evening taking

thrill rides together at a funfair.

Fear facilitates love partly by a process of “misattribution” i.e., explaining one’s emotional turmoil as due

to passionate feelings for whoever happens to be nearby (White et al, 1981). There is also a tendency to

cling to others for support when frightened (an effect called “affiliation under anxiety” by Stanley

Schachter, the Californian psychologist who first studied it). The idea is not entirely new; the Roman poet

Ovid recommended that young men take their female partners to the Coliseum to watch Christians being

torn apart by lions (the classical equivalent of horror movies). The fear induced by this spectacle, he

reckoned, would induce the woman to cling tightly to her escort.

Men wearing red are more attractive to women because they are seen a higher in status, while women in

red are attractive to men because of its passionate associations (Elliot & Niesta, 2008). These effects operate

unconsciously and probably derive from the fact that red is a significant colour in nature (signalling danger

and causing excitement). Reddening of the primate bottom advertises ovulation and hence evokes sexual

excitement; blushing may be human equivalent.

Sexual arousal primes us for close-bonded relationships. Gillath et al (2008) found that exposure to erotic

images motivated people to initiate and maintain close relationships, as indexed by access to intimacyrelated thoughts, willingness to self-disclose, to sacrifice oneself for a partner, and to settle conflict in a

postive manner. These effects were similar for men and women and were more pronounced if the sexual

stimuli were subliminal. Presumably this is because subliminal sex images are less likely to arouse

inhibitory attitudes such as disgust.

The Romeo & Juliet effect refers to the finding that when parents try to block a relationship in their children

which displeases them it tends to intensify their feelings for each another (Driscoll et al, 1972). This is either

because of the arousal effect described above, or through “cognitive dissonance” (the implicit reasoning

being that “if everyone is against our relationship and yet we are still together, then we must truly be in

love”). Either way, parents should be aware of the potential for their opposition to boomerang on them.

Does “absence make the heart grow fonder” or is it a case of “out of sight – out of mind”? Both proverbs

have a ring of truth and H.J. Eysenck suggested that the former is more likely to apply to introverts and the

latter to extraverts. There may also be sex differences; work-related travel enhances marital satisfaction for

men but diminishes it for women (Roehling & Bultman, 2002).

Clearly, there are different types of love. Canadian sociologist John Lee (1977) proposed six dimensions to

describe different types of love, applying Greek names to them. He posited three primary styles: (1) Eros – a

passionate, romantic kind of love, (2) Ludus – playful love, and (3) Storge – friendship based love. He also

listed three compounds: Pragma – practical love, Mania – possessive love, and Agape – altruistic love.

Lee’s system is still used but most researchers today prefer the “triangular” categorisation of Robert

Sternberg (1995), which has some similarities but a sounder psychometric basis. Stermberg distinguished

three main aspects of love, which appear in various proportions in different relationships: (1) Passion, a

heady cocktail of erotic desire and infatuation, (2) Intimacy, which features feelings of closeness and

attachment, and (3) Commitment, which is associated with long-term supportive contact with the partner.

Any particular relationship can be described in terms of the relative weighting of these three components.

“Romantic love”, for example, is a compound of passion and intimacy, while “companionate love” mixes

intimacy and commitment. If all three aspects are there Stermberg called it “consummate love”. If only

commitment is present then it is “empty love”.

Ahmetoglu et al (2010) looked at associations between the three styles and scores within the “Big-5”

personality system. Agreeableness correlated with all three types, while Conscientiousness went with

2|Page

Intimacy and Commitment only. Not surprisingly, Commitment went with age and longer relationships

while Passion went with youth and shorter relationships.

The three aspects show different time courses. Passionate love rises steeply at the beginning of a

relationship but declines just as sharply. Commitment is slower to develop but may be longer lasting.

Intimacy is intermediate in this respect (Garcia, 1998). Experiences of passionate love are reported from

early childhood (Hatfield et al, 1988) though boys of around 12 are loath to admit such feelings.

From a more evolutionary standpoint, Fisher et al (2002) proposed three separate motivational systems in

support of reproduction, each having its own neural correlates, chemistry and behaviours. (1) Lust evolved

to promote sex with any suitable partner; this is based in the hypothalamus and sex hormones testosterone

and oestrogen. (2) Attraction determines choice among mating partners, thus conserving courtship time and

energy; it is assumed to have a corticolimbic location with involvement of the neurotransmitters

epinephrine, dopamine and lowered serotonin. (1) Attachment evolved for cooperation with a mate to

provide parental care through the vulnerable years of infant development; this involves another set of

chemicals, particularly oxytocin, vasopressin and the endorphins.

Neuroimaging studies show that when romantic lovers view images of their partner there is activation of

the same reward circuitry that is stimulated by euphoriant/addictive drugs such as cocaine (Aron et al,

2005). These are the dopamine-rich areas of the limbic system, e.g., the ventral tegmental area and the

caudate nucleus. This finding has been replicated with Chinese participants (Xu et al, 2011), hence has

some cross-cultural validity. Activation of these brain areas by pictures of the loved one has been shown to

have analgesic effects, reducing the amount of pain experienced in the laboratory by about 40% (Younger et

al, 2010). The reward activations in the brain may be sustained for a long period in couples who report

continuing to love one another, although in these cases the brain-systems for attachment/bonding are also

involved (Acevedo et al, 2011).

Bartels & Zeki (2000) also used fMRI to locate brain activity in lovers looking at pictures of their loved one.

They also found increased activity in dopamine/reward centres, but equally interesting was their

observation that certain brain areas show reduced response (deactivation). This was mainly in cortical areas

associated with moral judgement and behavioural control. Other work by this UCL team has shown that

brain responses to images of a loved one are similar for men and women, and for gay and straight people

(Zeki & Romaya, 2010). There is also overlap between brain responses of lovers and mothers viewing their

children (Bartels & Zeki, 2004), particularly in brain circuits concerned with secretion of bonding

hormones.

Fisher’s third main system (attachment) derives partly from parent-child bonding. Oxytocin (as well as the

closely linked vasopressin) is produced in the hypothalamus and stored in the pituitary, to be discharged

into the blood during sexual arousal/orgasm, childbirth and breastfeeding. Apart from stimulating uterine

contractions and lactation, it supports trust and bonding between parents and between parent and child.

Apparently, the attachment system, which evolved initially to support parental care has been co-opted in

humans (and possibly other primates) to serve a new adaptive purpose, that of bonding together

reproductive partners so they will share parental duties long enough for their children to reach viability

(Diamond, 2004).

The link between oxytocin and motherhood is well known, but increased secretion of oxytocin (and also

prolactin – the lactating hormone) has also been observed in new fathers (Gordon et al, 2010). Moreover,

those fathers who were best at communicating and playing with their babies show the strongest increase in

these “empathy” hormones. Given these connections, it is not surprising that lovers display body language

and use terms of endearment reminiscent of parent-child love.

Other hormones and neurotransmitters have been implicated in love. Italian research suggests that the

experience of romantic love has much in common with obsessional-compulsive disorder, both being

characterised by immobilisation of thought and low levels of serotonin (Marazziti et al 1999). This being so,

3|Page

Prozac-type antidepressants that operate by elevating serotonin might interfere with the capacity to fall in

love or “cure” it once it has happened.

University of Pavia researchers have been that early-stage passionate love correlates with increased levels

of nerve growth factor in the blood (Emanuele et al, 2005). The meaning of this is not clear, but NGF

promotes nerve regeneration and healing and could account for the reputed health benefits of falling in

love. The effect is short-lived though; when long-term lovers were retested a year or so later their NGF

levels had returned to normal.

Liebowitz (1983) suggested that a key to the chemistry of love might be an endogenous amphetamine-like

substance called phenylethylamine (PEA). Since this is contained in chocolate, others speculated that eating

chocolate may be an attempt at self-treatment in people who are lonely and depressed. Unfortunately, it

seems that PEA in food (and there is more in cheese & sausages than chocolate) is rapidly metabolised and

little of it reaches the brain. Hence the craving for chocolate is probably more to do with the reward of its

sweetness than its capacity to substitute love.

Since some aspects of love derive from parent-child relationships, attachment styles acquired early life

(secure, anxious, avoidant, dismissing, etc) can be applied to adult relationships (Hazan & Shaver, 1987). It

is suggested that experiences like divorce and widowhood reactivate early attachment experiences, thus

giving them extra emotional power.

There is another sense in which childhood attachments connect with adult love experiences. There is

growing evidence that we imprint an image of our ideal partner on the basis of infantile experience of the

opposite-sex parent (Gyuris, et al, 2010). If reminiscence of certain physical and personality traits influences

partner choice, this could account for episodes of “love at first sight” and so-called “genetic sexual

attraction” (falling madly in love with a close family member from whom one was separated at a young

age). Something about the person we fall in love with reawakens memories (often unconscious ones) of our

early childhood attachments.

Love is one of the few areas of behaviour in which twin studies show little genetic input. One of the highest

genetic estimates is the one-third of variance reported by Rushton & Bons (2005). This leaves much room

for influences from the common family environment and from seemingly random factors (Waller & Shaver,

1994). In a sense, Cupid strikes “out of the blue”.

Zeki’s work finding that the brain areas concerned with critical and social judgement are deactivated by

love supports the idea that “love is blind”. Other research shows that we tend to idealise our partners,

attributing more favourable traits to them than to former partners. The earlier in the relationship, and the

more committed we are to them, the stronger is the “rose-tinted specs effect” (Geher et al, 2005). Being in

love also seems to disrupt the capacity to assess how much in love other couples are (Aloni & Bernieri,

2004). Those who were themselves “in love” were more confident in their ability to detect true love in the

body language of others but were actually less accurate in doing so.

Can we love more than one person at the same time? Perhaps not in Stermberg’s “Consummate” sense, but

in other ways we probably can. Parents certainly form deep bonds with several children and, because

Fisher’s three evolutionary systems are independent, it ought to be possible to simultaneously feel bonding

with one person, attraction to another, and lust for one or more others.

Other theorists have looked at passionate love as a quest to expand one’s sense of self by merging with our

partner. Couples who are in love refer to each other as their “better half” and describe themselves as an

“item”, thus incorporating their partner into their self-image. Ortigue, et al (2010) found that lovers

develop empathy that enables them to infer the intentions of their partner from minimal body language

cues better than strangers. This yearning for deep union with a partner may be part of an evolutionary

drive toward the ganging of organisms that has been developing since single-celled organisms became

multicellular.

4|Page

Is it useful to study the mechanisms underlying love? I would say yes, because it can help us to understand

the agony that is suffered by lovers around bouts of ecstacy. We will also be better placed to deal with the

deficits seen in certain individuals who seem to lack the capacity to love. These can be disabling, as in

autism, or positively dangerous, as in psychopathy. But discussion of these topics must await next month’s

exciting installment, called “lovesickness”.

References

Acevedo, B.P. et al (2011) Neural correlates of long-term intense romantic love. Social and Cognitive Affective

Neuroscience, Jan 5, 10, 1093 (on line publication).

Ahmetoglu, G., Swamic, V. & Chamorro-Premuzic, T. (2010) The relationship between dimensions of love,

personality and relationship length, Archives of Sexual

Behaviour, 39, 1181-1190.

Aloni, M. & Bernieri, F.J. (2004) Is love blind? The effects of experience and infatuation on the perception of

love. Journal of Non-verbal Behaviour, 28, 287-295.

Aron, A. et al (2005) Reward, motivation and emotion systems associated with early stage intense romantic

love. Journal of Neurophysiology, 94, 327-337.

Bartels, A. & Zeki, S.(2000) The neural basis of romantic love. Neuroreport, 11, 3829-3834.

Bartels, A. & Zeki, S. (2004) The neural correlates of maternal and romantic love. Neuroimage, 21, 1155-1166.

Diamond, L.M. (2004) Emerging perspectives on distinctions between romantic love and sexual behaviour.

Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13, 116-119.

Driscoll, R., Davis, K.E. & Lipetz, M.E. (1972) Parental interference and romantic love: The Romeo & Juliet

effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 24, 1-10.

Elliot, A.J. & Niesta, D. (2008) Romantic red: red enhances men’s attraction to women. Journal of Personality

and Social Psychology, 95, 1150-1164.

Emanuele, E. et al (2005) Raised plasma nerve growth factor levels associated with early-stage romantic

love. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 20, 1-7.

Fisher, H.E., Aron, A., Mashek, D., Li, H. & Brown, L.L. (2002) Defining the brain systems of lust, romantic

attraction and attachment. Archives of Sexual Behaviour, 31, 413-419.

Fisher, H.E., Aron, A. & Brown, L. (2005) Romantic love: An fMRI study of a neural mechanism for mate

choice. The Journal of Comparative Neurology, 493, 58-62.

Garcia, C.Y. (1998) Temporal course of the basic components of love throughout a relationship. Psychology

in Spain, 2, 76-86.

Geher, G. et al (2005) Motivational underpinnings of romantic partner perceptions: psychological and

physiological evidence. Journal of Social & Personal Relationships, 22, 255-281.

Gillath, O. et al (2008) When sex primes love: subliminal sexual priming motivates relationship goal

pursuit. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34,1057-1069. Gordon, I. et al (2010) Oxytocin and the

development of parenting in humans. Hormones and Behaviour, 68, 377-382.

Gyuris, P. et al (2010) The effect of childhood experiences on mate choice in personality traits: homogamy

and sexual imprinting. Personality and Individual Differences, 49, 467-472.

Hatfield, E. et al (1988) Passonate love: How early does it develop? Journal of Psychology and Human

Sexuality, 1, 35-51.

Hazan, C. & Shaver, P. (1987) Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality

and Social Psychology, 52, 511-524.

Jankowiac, W.R. & Fischer, E.F. (1992) A cross-cultural perspective on romantic love. Ethnology, 31, 149-155.

Kellerman, J., Lewis, J. & Laird, J.D. (1989) Looking and loving: the effects of mutual gaze on feelings of

romantic love. Journal of Research in Personality, 23, 145-161.

Lee, J.A. (1977) A typology of styles of loving. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 3, 173-182.

Liebowitz, M.R. (1983) The Chemistry of Love. Boston: Little Brown.

Marazziti, D. et al (1999) Alteration of the platelet serotonic transporter in romantic love. Psychological

Medicine, 29, 741-745.

Ortigue, S. et al (2010) Implicit priming of embodied cognition on human motor intention understanding in

dyads in love. Journal of Personal and Social Relationships, 27, 1001-1015.

Roehling, P.V. & Bultman, M. (2002) Does absence make the heart grow fonder? Work-related travel and

marital satisfaction. Sex Roles, 46, 279-293.

Sternberg, R.J. (1995) Love as a story. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 12, 541-546.

5|Page

Rushton, J.P. & Bons, T.A. (2005) Mate choice and friendship in twins: evidence for genetic similarity.

Psychological Science, 16, 555-559.

Waller, N. G. & Shaver, P.R. (1994) The importance of non-genetic influences of romantic love styles.

Psychological Science, 5, 268-274.

Walster, E. & Berscheid, E. (1971) Adrenaline makes the heart grow fonder. Psychology Today, June, 47-62.

White, G.L., Fishbein, S. & Rutstein, J. (1981) Passionate love and the misattribution of arousal. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 41, 56-62.

Wilson, G.D. & McLaughlin, C. (2001) The Science of Love. London: Fusion Books.

Xu, X. et al (2011) Reward and motivation systems: A brain mapping study of early-stage intense romantic

love in Chinese participants. Human Brain Mapping, 32, 249-257.

Younger, J. et al (2010) Viewing pictures of a romantic partner reduces experimental pain: involvement of

neural reward systems. PloS ONE, 5(10) e/33309 (online journal).

Zeki, S. & Romana, J.P. (2010) The brain reaction to viewing faces of opposite and same-sex romantic

partners. P loS ONE, 5(12), e/15802 (online journal).

©Professor Glenn Wilson, Gresham College 2011

6|Page