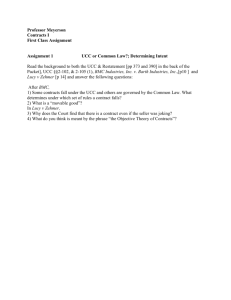

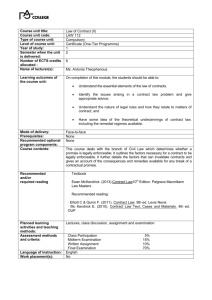

INTRODUCTION-TO

advertisement

INTRODUCTION TO CONTRACTS OR THE WORLD OF ENFORCEABLE PROMISES INTRODUCTION CONTRACTS--CORNERSTONES OF STABILITY IN HUMAN AFFAIRS Stability can only exist in a society that has a system that will right wrongs and enforce promises. In a society where one man may injure another or break his word with impunity, chaos and anarchy reign. As soon as Man left all fours to stand erect, he began to create rules which would remedy wrongs within his group and thereby allow group stability to evolve. Although the rules that develop from one society to another may differ widely, their functions are the same: (1) to see that society is safe from those individuals within the society that do not follow the rules--the function of Criminal Law; (2) to see that a man who receives injury at the hands of another obtains compensation--the function of Tort Law; and (3) to see that the reasonable expectations of one man which are the result of the promises of another are met--the function of Contract Law. In this chapter, we will take our first peek at what will become an extended look at Contract Law. As you come to understand more about contracts, you will see that you enter numerous contracts every day, many times without any conscious awareness that these events have legal significance. It is this abundance of contracts coupled with our unconscious use of them that makes contracts the cornerstones of stability in our lives. CONTRACTS AS ENFORCEABLE PROMISES A contract can be simply defined as an agreement that a court will enforce. Unfortunately, this simple and usual definition does not provide much aid in helping us distinguish which of our agreements--our promises--are enforceable and which are not. 1 Our lives are full of promises, many of which we do not keep, and even some of which we make with no intention of keeping. Have you ever made promises such as these (I know I have): "Sure, I'll call you sometime next week"; "I promise I'll never look at another (man)(woman)"; or "If you send the money, I promise to study harder". The difference between these promises and contractual promises is that these promises are not generally made under circumstances where a reasonable person would expect to be legally accountable for failing to keep them. What makes promises legally enforceable is the circumstances under which they are made. Believe it or not, each of the above promises could be legally enforceable under the right circumstances. Such circumstances can be categorized and analyzed as contractual "elements". When a promise is made under circumstances which establish all the "elements" of contractual responsibility, then the promise will be enforceable in court. THE ELEMENTS OF A CONTRACT Those circumstances which are otherwise known as the elements of a contract are as follows: 1. An OFFER is made; a proposal to enter into an agreement--the person making the offer or proposal is called the "Offeror". 2. There is ACCEPTANCE of the offer; the person to whom the offer is made accepts the terms of the offer and agrees to enter the agreement--this person is called the "Offeree". 3. The agreement is supported by CONSIDERATION; both parties have obtained rights and obligations as a result of making the agreement. 4. Both parties have the legal CAPACITY to enter contracts; neither party is a minor, is insane, or is intoxicated. 5. The agreement has LEGALITY; it is neither illegal or against public policy. 2 Circumstances which establish OFFER, ACCEPTANCE, CONSIDERATION, CAPACITY, and LEGALITY show that a legally binding contract has been made. Each of these five elements of a contract will be discussed at length in future chapters, for now, here is an example. Case 1: Lets say I'm interested in selling my 1977 Vega station wagon, a semi-clunker, and that you (for some unknown reason, perhaps, lack of taste) are interested in buying a cheap car with "personality". You say to me: "I'll give you $500.00 for your Vega". I immediately reply: "you've got a deal". A contract for the purchase of the Vega has been made. The OFFER is your proposal to buy my Vega; the ACCEPTANCE, is my agreement to sell. The CONSIDERATION is our exchange of promises by which we both acquired new rights and obligations. You acquired the right to have my car transferred to you and the obligation to pay me $500.00. I acquired the right to collect $500.00 from you and the obligation to transfer my car to you. The agreement appears to be neither illegal nor against public policy so the "element" of LEGALITY would be met. Assuming neither of us is a minor, is insane, or is intoxicated, there is CAPACITY and our exchange of promises has created an enforceable contract. CLASSIFICATION OF CONTRACTS INTRODUCTION Although every "true" contract comes into existence as a result of circumstances establishing the elements discussed above, various types of contracts may be formed by such circumstances. Because different legal principles apply to the various types of contracts, classification becomes necessary to describe the legal relationship in question. The various classifications of contracts are discussed below. UNILATERAL AND BILATERAL CONTRACTS The differences between UNILATERAL contracts and BILATERAL contracts are the consideration exchanged and the time of formation. In a unilateral contract, a promise is exchanged for an act; in a bilateral contract, a promise is exchanged for another promise. A unilateral contract does not come into existence until 3 the requested act is completed. A bilateral contract, on the other hand, is formed the moment the promises are exchanged--the moment the offer is accepted with a return promise. The contract for the sale of my Vega in Case 1 is an example of a bilateral contract. It was formed by our exchange of promises and came into existence the moment I accepted your offer. If you were sitting in my classroom, and I made the following proposal to you--"If you will go to the coffee machine and bring me back a cup of coffee, I will pay you 50 cents."--this would be an offer to form a unilateral contract. I have made a promise--my offer--and have asked for an act in return--your acceptance would be performing the act. A unilateral contract would be formed when you finished performing the requested act by bringing the coffee to me at which time I would become obligated to keep my promise and pay you the 50 cents. EXPRESS AND IMPLIED CONTRACTS These types of contracts differ in the manner the agreement of the parties is manifested. In an EXPRESS contract the terms are expressed by the parties through words, either oral or written. In an IMPLIED contract, the agreement is inferred from the conduct of the parties. In the Vega sale, we expressed the terms of our agreement in words, therefore, it would be an express contract. An example of an implied contract would be a usual trip to the doctor's office. You would go seeking services for which you expect to pay, and the doctor would provide the services with an expectation of payment. Usually, no terms are discussed, however, by the conduct of accepting the services an implied contract is formed under which you are liable for the reasonable value of the services provided. Another example would be walking into a store, picking up a newspaper marked 25 cents, putting 25 cents on the counter and walking out. As long as no words are spoken, but an offer and acceptance--an agreement--is observed in the conduct of the parties, the contract formed is classified as implied. 4 NOTE: Implied contracts such as those mentioned above, are called IMPLIED-IN-FACT contracts. There is another type of binding relationships called IMPLIED-IN-LAW contracts or QUASI CONTRACTS. These are not "true" contracts, but will be discussed more fully below. EXECUTED AND EXECUTORY CONTRACTS The difference here is whether the obligations created by the contract have been performed. Where both parties have fully performed their obligations under the contract, the contract is classified as EXECUTED; where all obligations remain unperformed, the contract is termed EXECUTORY. Where some of the obligations have been performed and others remain unperformed, the contract is usually called "partially executed", however, "partially executory" is just as descriptive. The contract for the sale of my Vega would be executory until I transferred the car and you paid the $500.00; on the performance of these obligations, the contract would be executed. The visit to the doctor's office mentioned above would be partially executed as soon as the doctor rendered the services; it would become executed when you paid for them.This difference between executory and executed contracts can be significant in such areas as illegality, consideration, contract modification, damages for breach of contract, and contracts required to be in writing (the Statue of Frauds). VALID, VOIDABLE, AND UNENFORCEABLE CONTRACTS A VALID contract is one that possesses all the elements necessary for contract formation and there are no rules of law that would prevent its enforcement. A VOIDABLE contract is one which may be avoided by one or both of the parties. The law usually gives a party who enters a contract under a legal disadvantage the option to either enforce the contract or get out of it. For example, a minor does not have the legal capacity to enter contracts and is given the right to avoid (disaffirm) contracts. Also, a party induced to enter a contract by the false representations of the other party may avoid the contract. If the party having the right to avoid the contract does not 5 choose to do so, the contract will be enforced. An UNENFORCEABLE contract is one which has all the elements of a contract, but some rule of law prevents its enforcement. For example, the Statute of Frauds requires that certain contracts be in writing to be enforceable. One such type of contract is a contract for the sale of goods for a price of $500.00 or more. Under the Statute of Frauds, our executory contract for the sale of my Vega would not be enforceable as it was not in writing; however, if we partially executed the contract, certain exceptions to the Statute of Frauds (which you will learn later) would permit the contract to be enforced. Another rule making otherwise valid contracts unenforceable is the Statute of Limitations which requires that a court action to enforce a contract be started within a certain period of time after its creation, say, six years. After six years, the contract would become unenforceable. NOTE: Some authors include in this area of classification the term "void" contracts; however, this term is a misnomer, the proper term being a "void" agreement. A void agreement never becomes a contract, usually because one or more of the elements are missing. An agreement to do something illegal--a "hit contract", for example--never becomes a contract, therefore, void agreement is the better term. FORMAL AND INFORMAL CONTRACTS The most common example of a FORMAL contract is a contract under seal. Such a contract can be made by having a "seal" impressed on the paper, by having the word "seal" at the end, or simply by having the letters "L.S." at the end. Any other contract is called an INFORMAL contract no matter how long or complex it may be. For example, a friend of mine develops shopping center management contracts which may be as many as several hundred pages long. Unless they are under seal, they are still called "informal" contracts. Obviously, most contracts are informal contracts. Although at early common law there was a distinction between informal contracts, today most jurisdictions treat them the same. 6 formal and In those jurisdictions that recognize a difference, they merely have a presumption of consideration in formal contracts. The presumption may be rebutted however. QUASI CONTRACTS OR CONTRACTS IMPLIED IN LAW As stated above, QUASI CONTRACTS are not contracts at all. Quasi contracts are "make believe" contracts--they arise in non-contractual circumstances which are treated as binding in order to prevent the unjust enrichment of one party at the expense of another. They are CONTRACTS IMPLIED IN LAW rather than implied from conduct establishing the elements of a contract. Even though many Rules of Law represent the collective wisdom of centuries, in some circumstances if a Rule is applied "blindly" injustice will result. Trying to get the Rule to justly fit the circumstances, is like trying to fit a square peg into a round hole. In order to prevent such injustices, the law has created what are called "legal fictions"--legal make believes--so that the square peg can fit into the round hole. Quasi contracts are the legal make believes used to prevent injustice which would result form the application of the principles of contract formation. As we continue to examine other areas of the law, we will encounter other legal make believes. Case 2: Farley Farnsdinkel comes home to find several people on his roof working away putting new tile on the roof. Farley did not hire anyone to work on his roof; however, rather than inquire as to why these people are on his roof, he asks if they would like some lemonade. When the workmen finish, they present Farley with a bill made out to Hilbert Hinkley, Farley's next door neighbor. Farley then tells the workmen that they did the wrong roof, and that he will not pay because he did not order the job. The roofing company sues Farley. Applying the rules of contract formation, no true contract could be found between Farley and the roofing company. There is certainly no express contract, and Farley's conduct could not constitute an implied acceptance because the job was already in progress when he came home. While it is true that there is no contract between Farley and the roofing company, a determination of no liability would leave Farley unjustly enriched with a new roof at the expense of the roofing company. The court would find a quasi contract under which it would hold Farley liable for the reasonable value of the services provided by the roofing company. 7 NOTE:Under quasi contract theory, since the liability is founded on the unjust enrichment of one party rather than upon a true contract, the court will only hold that party liable to the extent of the unjust enrichment. The theory of recovery in quasi contract is called QUANTUM MERUIT, or in English: "as much as he deserves". The actual amount awarded may well be less than the contract price. THE TWO FACES OF CONTRACT LAW INTRODUCTION I realize that you may not be overjoyed at having to learn one set of rules called "Contract Law". Unfortunately, because of the manner in which "Contract Law" has developed in our country, you will need to learn two areas of "contract Law": one based on the common law and one on the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC). Do not despair, there is a great deal of overlap between the "Contract Law" of the UCC which governs contracts for the sale of goods and the common law of contracts which regulates most other contracts. These "two faces of Contract Law" are discussed below. THE COMMON LAW OF CONTRACTS The common law of contracts developed over the centuries, as did all common law, on the basis of recorded case decisions. In the United States with each state a separate jurisdiction, the common law of contracts developed with some degree of diversity. In an effort to create greater uniformity and clarity in the common law of contracts, the American Law Institute published, in 1932, a multi-volume treatise on contract law entitled the Restatement of the Law of Contracts. The Restatement was written by the best legal scholars, judges, and lawyers. The Restatement is not law, like a statute would be; however, as it represents the thinking of the best legal minds as to what the Law of Contracts ought to be, it has influenced the common law of contracts since its publication. In many of the cases in this volume, the judges have supported their statements with quotations from the Restatement. In 1979, a revision of the original Restatement was completed, therefore, most recent cases will include 8 citations to the Restatement of the Law (Second) of Contracts. The "common law of contracts" that you will be learning in this course will be based primarily on the general principles of contract law contained in the Restatement. These principles apply to contracts other than those for the sale of goods. They apply to such contracts as: contracts for services; contracts for the sale of land; construction contracts; contracts for loans; insurance contracts; employment contracts; etc. THE UNIFORM COMMERCIAL CODE The needs of commercial transactions have traditionally been different from the needs of other types of contracts. In the case of the sale of goods, there is need for speed and certainty as such transactions may involve a series of contracts all taking place within minutes. For example, when a customer orders goods from a retailer in one state, it may well precipitate a call to the wholesaler located in another state, and finally, a call to the manufacturer in yet a third--three contracts involving three states concerning the same goods. The sale of goods, therefore, requires a set of rules that are uniform from state to state and provide for certainty in speedy transactions. The UCC was written to accomplish these objectives for contracts involving the sale of goods as well as other commercial transactions, e.g., commercial paper and secured transactions. The UCC was prepared under the joint sponsorship of The American Law Institute and the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws. The Code was originally approved by its sponsors and the American Bar Association in 1952. Since 1952, the Code has undergone revision and amendment, and every so often an "Official Text" is published, the latest in 1979. Most importantly, the UCC has been enacted as statutory law in all states except Louisiana, most the statutory adoptions being in the 1960s. Although there is some minor variation from state to state as the result of legislative amendments, the bulk of the UCC is the law of the United States in regard to commercial transactions. 9 A COMPARISON OF THE TWO FACES The law of contracts can be examined in terms of five areas: (1) formation; (2) construction or interpretation; (3) performance; (4) breach; and (5) remedies. In each of these areas, the law of sales under the UCC elaborates upon and modifies the common law of contracts. In all areas, the UCC is more specific as the intent of the authors was to cover every contingency that could arise in a transaction involving the sale of goods. The UCC allows for the formation of a contract where the common law would not, it provides for an interpretation which will supply terms if the parties fail to include them, it contains specific rules for contract performance, it provides for each parties duties on the breach of the other, and it includes remedies unavailable under the common law. In each of the following chapters on Contract Law, the differences between the common law of contracts and the UCC will be noted. You are advised to become familiar with the UCC at your earliest opportunity. When a UCC section is cited in a chapter, you should go to the appendix and read the section there. If you start to become familiar with the UCC now, it will prove enormously helpful when you get to the chapters on sales where you will be using the UCC exclusively. 10