Democracy began with the ancient Greeks in the sixth century BC

advertisement

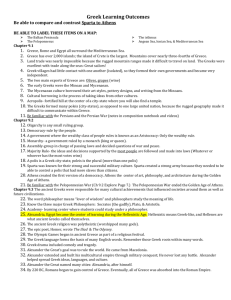

GREEK DEMOCRACY: THE POLIS Democracy began with the ancient Greeks in the sixth century BC. When we speak of the Greeks of that period, we are not speaking of a united country but of groups of Greek-speaking people, each of whom formed a city-state known as a polis (plural: poleis). The polis included an urban center, outlying farm areas, and small neighboring villages. Most of the poleis were small in size; only three had a population of over twenty thousand citizens. They varied in geographical size as well: the area of Sparta was 3,200 square miles; the area of Corinth only 330. By way of comparison, the area of Harlan County is 467 square miles. The polis was much more than a political unit. It was the Greeks' principal expression of community. Aristotle wrote that "man is a creature who is born to live in a polis." Sophocles said that a man without a polis is dead. In other words, the polis gave Greeks their civic identity. The polis provided justice and defended its members against outside enemies. It assured that proper respect would be paid to the gods. It provided a forum for the discussion of community issues and facilitated commerce and trade. Fifth century Athens was the largest polis. It had a population of approximately 40,000 adult male citizens and a total population of well over a hundred thousand when women, children, foreigners, and slaves are included. Only freeborn adult males native to Athens could vote, but wealth was not a bar to political participation. Women, though not voting citizens, had certain basic rights, but had to have a man speak for them in public proceedings. The voting citizens made up the assembly which was the most important political institution as it controlled the purse and made major decisions. There was also a smaller Council of 500 which served as an executive committee between meetings of the assembly. The military was under the immediate control of ten generals, elected annually. Originally, court proceedings were in the hands of nine archons, also elected annually, but by the fifth century, their authority had been sharply limited. Most trials of that period were conducted by jury. Each year 6,000 citizens were elected to serve on juries. Juries usually had 100 to 1,000 members in attendance. There were no judges in the modern sense (though an archon kept order) and no lawyers. Each party attempted to prove its case through persuasive speech. Trials lasted one day and were decided by majority vote of the jury. This reflects the Greek belief that "the cumulative political wisdom of the majority…would outweigh the eccentricity and irresponsibility of the few." A common fear in Greek society of the time was of the "turannos" or tyrant. A tyrant was a ruler who exercised sole authority, whether for good or bad. This fear resulted in a custom in Athens known as ostracism. A citizen who had become too prominent or who had been responsible for a failed policy could be exiled and sent to live outside the polis for ten years. At the end of that time, or sooner if the assembly voted to recall him, he could return without penalty. Questions (answer in Cornell format so they can be put in your notebook when returned): 1. What was a polis? 2. Why was the polis the source of Greek civic identity? 3. Which was the largest polis in population? 4. Who was eligible to be a citizen and vote in Athens? 5. What was the status of women in Athens? 6. Who made up the Athenian assembly? 7. What was the assembly’s function? 8. What method was used to decide court cases? 9. How did a trial in ancient Athens differ from a modern trial? 10. What was ostracism? 11. Why did the Greeks ostracize citizens? 12. What does modern American democracy have in common with ancient Greek democracy?