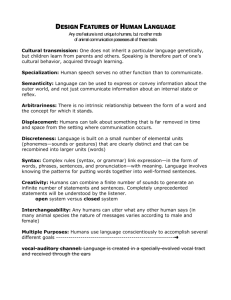

THOUGHT and LANGUAGE

advertisement

THOUGHT and LANGUAGE(1) (PS) 89-99 (PLLT) 20-30 THE ELEMENTS OF LANGUAGE: Language: it’s the primary means through which we communicate our thoughts to others. It has two basic elements: 1) symbols, such as words, 2) grammar, rules for combining symbols. Humans can create and understand an infinite number of sentences, which are created from just a few dozen categories of sounds. There are different levels in which language is organized according to rules: Phoneme: a phoneme is the smallest unit of sound that affects the meaning of speech, the representation of a sound. Each spoken language consists of thirty to fifty phonemes. English has twenty-six letters, but it has about forty phonemes. The letter sounds are phonemes. Morpheme: it’s the smallest unit of language that has meaning. They can be free-morphemes if they can stand alone (dog, car) or bound-morphemes if they can’t stand alone such as prefixes and suffixes. Words: it’s a linguistic unit that carries a meaning and is formed of one or more morphemes. Syntax: it’s the set of rules that govern they way words are combined to form phrases and sentences. Semantics: it’s the set of rules that govern meaning of words and sentences. After having studied linguistics for so many years, Noam Chomsky argued that if linguistics studied ONLY the language that people produce, they would never uncover the principles that account for all the sentences that people create. He proposed that behind surface structures (word connections that people produce), there is a deep structure (abstract representation of the relationships expressed in a sentence). Chomsky’s ideas encouraged psychologists to analyze not just verbal behavior and grammatical rules but also mental representations. UNDERSTANDING SPEECH: When we listen to someone speak, we develop an internal description of the ideas intended by the speaker’s idea. Knowledge, experience and expectations help us construct a mental representation of what is said. This construction occurs at several levels: Perceiving words and sentences: people use their vast store of knowledge about grammatical structure, the meaning of words, and the world itself in order to process and understand language Using context and Scripts: people use context to impose meaning on stimuli. The tone of voice may also be relevant in the understanding of a word or phrase. An individual’s educational and cultural background forms part of the context that shapes their understanding of a communication. That background may determine how a listener interprets ambiguous stimuli. Conventions and Nonverbal Cues: social conventions are commonly accepted practices and usage. Words or phrases alone may not be so literal there may be underlying social meanings to them. “Do you know where downtown is?” – “Yes”. People are guided to an understanding of conversations by nonverbal cues. LEARNING TO SPEAK: Stages of Language Development: Children learn languages with impressive speed and regularity. Developmental psychologists have described the steps in language acquisition: Babblings: they are the first words infants make that resemble speech that begin at about four months of age. Infants of all nationalities make the same babbling sounds. When children are 10-12 years old, they can understand a few words, but more than they can say. Proper names and object words are among the first words they understand. Nouns for simple object categories are acquired before more general nouns or more specific names. Children reduce words to easier shorter forms, like “mih” for milk, but they make themselves understood by using gestures, intonations, facial expressions, and interminable repetitions. They may also “generalize” the words they know because their language is limited, not because they can’t identify the differences among objects. First sentences: When children 18-24 months old, they usually have a vocabulary of fifty words. Then, their language “suffers” a rapid acceleration: they may learn several new words a day and begin to put words together. At first, their sentences consist of two-word pairs that are telegraphic utterances because they leave out any word that is not absolutely essential. For example; “Give book”, “Mommy give”. The child also emphasizes intonation to indicate a question and word stress to indicate location or new information. After some months, children are able to say three-word sentences that may still be telegraphic but containing the usual subject-verb-object form of adult sentences. Other words and word endings begin appearing, too, such as the suffixing, the proposition in and on, the plural –s, and some irregular past tenses. When children learn the suffix –ed for the past tense, they over apply the rule to irregular verbs that they previously used correctly. Complex sentences: When children turn three or so, they start using auxiliary verbs and asking wh- questions. They begin to put together clauses to form complex sentences. Until they are about five years old, they join events in the order in which they occur and understand sentences better if they follow this order. HOW IS LANGUAGE LEARNED? Children pick up the specific content of language from the speech they hear around them; however, there’s still debate to answer the question: “How do we learn a language?”. There have been many studies on how children learn a language as well as how they learn syntax. Here are some of the most important approaches to explain how we learn a language: 1. Conditioning, Imitation and Rules: perhaps children learn syntax because their parents reinforce them for using it. However, parents are more concerned about what is said than about its form. That means that parents do not correct the child and reinforce him for grammatical correctness; therefore, we can say that operant conditioning cannot fully explain the learning of syntax. Extreme behavioristic position: they claim that children come into the world with a tabula rasa, a clean slate having no preconceived notions about the world or about language, and that these children are then shaped by their environment and slowly conditioned through various schedules of reinforcement. The behavioristic approach: it focused on the immediately perceptible aspects of linguistic behavior – the publicly observable responses - and their relationships or associations between those responses and events in the world surrounding them. They may consider effective language behavior as the production of correct responses to stimuli. Therefore, verbal behavior is controlled by its consequences. When consequences are rewarding, behavior is maintained is increased in strength and frequency. When consequences are punishing, or there is total lack of reinforcement, the behavior is weakened and eventually extinguished. o Critique: Children learn syntax most rapidly when adults offer simple revisions of their sentences, implicitly correcting their syntax, and then continue with the topic they are discussing. But why if children learn syntax by imitation, they overgeneralize rules, such as the one for making the past tense? Neither conditioning nor imitation seems entirely adequate to explain how children learn a language. Children have to analyze themselves the underlying patterns in the mixture of language examples they hear around them. Today, virtually no one would agree that Skinner’s model effectively explains how we acquire and develop language. 2. Mediation: it justifies the claim that the word or sentence elicits a “mediating” response that is self-estimulating. That self-estimulation was called a “representational mediation process”, which is a really covert and invisible process within the learner. This theory just tried to explain the abstraction, but the abstract nature of language and the relationship between meaning and expression were unresolved. They couldn’t explain the underlying meaning of language (what is said beyond words; affective experiences) either. Jenkins and Palermo (1964): Within a behavioristic framework, claimed that the child may acquire frames of a linear pattern of sentence elements and learn the stimulus-response equivalences that can be substituted within each frame; imitation was an essential aspect of establishing stimulus-response associations. This theory couldn’t explain the abstract nature or language either because the child’s creativity and the interactive nature of language acquisition. It didn’t even touch generic and interactionist domains. 3. Biological bases for Language Acquisition (Nativist approach): some argue that humas are “biologically programmed” to learn language. This is reflected in the unique speech-generating properties of human mouth and throat, as well as in brain regions. The term nativist is derived from the fundamental assertion that language acquisition is innately determined, that we are born with a genetic capacity that predisposes us to a systematic perception of language around us, resulting in the construction of an internalized system of language. Eric Lennenberg (1967): proposed that language is a “speciesspecific” behavior and that certain modes of perception, categorizing abilities, and other language-related mechanisms are biologically determined. Chomsky (1965): suggested that human beings are born with a Language Acquisition Device – LAD – that allows children to gather ideas about the rules of language, without being aware of doing so. Then they use those ideas to understand and construct their native language. There are four innate linguistic properties described by Chomsky’s LAD theory: o The ability to distinguish speech sounds from other sounds in the environment o The ability to organize linguistic data into various classes that can later be refined o Knowledge that only a certain kind of linguistic system is possible and that other kinds are not o The ability to engage in constant evaluation of the developing linguistic system so as to construct the simplest possible system out of the available linguistic input. Chomsky’s theory explained aspects of meaning, abstracteness, and creativity more adequately. Elizabeth Bates: claimed that we don’t need to assume a special LAD to understand language acquisition. For her, the development of children’s language is influenced by the development of their cognitive skills, that is, children leaner short words before long words because limitations in short-term memory and other cognitive abilities lead them to learn easy things before harder ones. Universal Grammar (UG): researchers in the nativist tradition have continued this line of inquiry through a genre of child language acquisition research that focuses on what has come to be known as Universal Grammar, which claims that all human beings are genetically equipped with abilities that enable them to acquire language. These researchers expanded the Chomsky’s LAD theory into a system of universal linguistic rules. Universal Grammar (UG) research is attempting to discover what it is that all children, regardless of the language they hear around them (environmental stimuli) bring to the language acquisition process. These researchers demonstrated that a child’s language is SYSTEMATIC at any stage ant that the child is constantly forming hypotheses on the basis of the input (words) received and then testing those hypotheses in speech. As the child’s language develops, those hypotheses are continually revised, reshaped, or sometimes abandoned. Nativist studies of a child language constructed hypothetical grammars (descriptions of linguistic systems) of child language, although such grammars were still based on empirical data. They approached the data with few preconceived notions about what the child’s language ought to be, and probed the data for internally consistem systems. Their research led them to take some giant steps in understanding the process of first language acquisition. The early grammars of child language were referred to as pivot grammars, where the first word is called “pivot”; for example, “my, the, that” which could be associated with an “open word”; for example, “cap, horsie, milk, or sock”. In this case, children constitute a sentence: pivot + open word. This process generates neurons connections, which will grow in complexity as a child becomes adult. The above mentioned approaches within the nativist framework have made at least three important contributions to our understanding of the first language acquisition process: a. freedom from the restrictions of the so-called “scientific method” to explore the unseen, unobservable, underlying, abstract, linguistic structures being developed in the child b. systematic description of the child’s linguistic repertoire as either rulegoverned or operating out of parallel distributed processing capacities c. the construction of a number of potential properties of Universal Grammar However, these ideas leave a very narrow window opportunity for language learning. That is, after thirteen or fourteen years of age, people learn a [second] language more slowly and virtually never learn to speak it without an accent. Therefore, a person must be exposed to speech before a certain age. 4. Functional Approaches: researchers within the functional approach have come to the conclusion that 1) language is one manifestation of the cognitive affective ability to deal with the world, with others, and with the self; 2) generative rules that were proposed under the nativistic framework were abstract, formal, explicit, and quite logical, yet they dealt specifically with the “forms” of language and not with the deeper “functional” levels of meaning constructed from social interaction. Bloom (1971): cogently illustrated the relationships in which words occur in telegraphic utterances (pivot grammar). For example, in the utterance “Mommy sock”, sheound at least three possible underlying relations: agent-action (Mommy is putting the sock on), agent-object (Mommy sees the sock), and possessor-possessed (Mommy’s sock). With this, she demonstrated that children learn underlying (deeper) structures, and not superficial word order. She, along with Jean Piaget, Dan Slobin and others, concreted the way for a new way of child language study, this time centering on the relationship of cognitive development to first language acquisition. She noted that “an explanation of language development depends upon an explanation of the congnitive underpinnings of language: what children know will determine what they learn about the code for both speaking and understanding messages”. Child language researchers are in the process of pointing out the rules of the functions of language, and the relationships of the forms of language to those functions. Jean Piaget (1969): described overall development as the result of children’s interaction with their environment, with a complementary interaction between their developing perceptual cognitive capacities and their linguistic experience. What children learn about language is determined by what they already know. Dan Slobin (1971, 1986): demonstrated that in all languages, semantic learning depends on cognitive development and that sequences of development are determined more by semantic complexity than by structural complexity. Determined that there are two major pacesetters to language development: on the functional level, development is paced by the growth of conceptual and communicative capacities, operating in conjunction with innate schemas of cognition; and (2) on the formal level, development is paced by the growth of perceptual and information-processing capacities, operating in conjunction with innate schemas of grammar. Holzman (1984): proposed that “a reciprocal behavioral system operates between the language-developing infant-child and the competent [adult] language user in a socializing-teaching-nurturing role. Berko-Gleason (1986): they looked at the interaction between the child’s language acquisition and the learning of how social systems operate in human behavior. BILINGUISM: Children who are raised in bilingual environments seem to show an enhanced performance in each language if it happens before the critical period. There is evidence that “balanced bilinguals”, those who master two languages, are superior to other children in cognitive flexibility, concept formation, and creativity. There is evidence that the immersion in an English-only program may do considerable educational harm to children who enter school with no English-language background. WHAT DO YOU THINK? Can nonhumans learn a language? Do people from different languages perceive and think about the world in the same way? Does language shape perception or do environmental conditions are culturally based learning shape attention, perception, and the words used to describe important stimuli and events? Language directly influences perception, which leads to a greater perceptual ability to discriminate among “similar” objects. However, we cannot say that language causes the differences in perception, but also the need and frequency of use and the need for certain objects.