Reinach-An Intellect.. - Buffalo Ontology Site

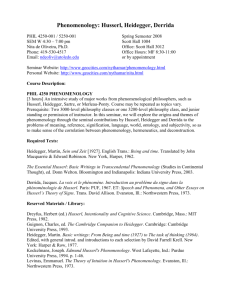

advertisement