FinalExam

advertisement

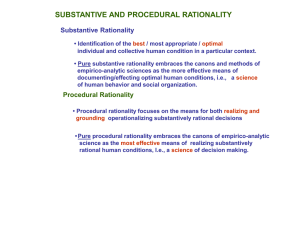

Discuss the different approaches to decision making that public managers might employ. What are the relative strengths and weaknesses of each approach? The traditional managerial approach to decision-making, also called the rationalcomprehensive model, stresses the need for rationality in decision making. It seeks to introduce rationality by reducing the number of alternatives and values that must be considered, assuring that the administrator knows how to make rational decisions and providing sufficient information for that process. Specialization narrows the range of alternatives and value assessments by limiting jurisdictional authority; the Department of Agriculture need not be concerned with the administration of justice, for example. Heirarchy limits managerial authority by clearly defining that authority. Formalization narrows choices by specifying the factors and information to be weighed when making a decision, thus further narrowing discretion. Merit requirements seek to assure that administrators are capable of making rational decisions unclouded by partisan politics, and that administrators have the information and technical expertise required for the task at hand. The rational-comprehensive model asks us to determine the objectives, consider the possible means to achieve those objectives, and choose the best alternative. One significant problem with this approach is that objectives are not always clear—there is often no one way to define “equitable” or “the public interest.” Thus the rationalcomprehensive model assumes a degree of universality that may not necessarily exist. Also, defining objectives can be difficult when the political support for a given program originates with a coalition of diverse interests. Further, it may be unrealistic given time constraints for a public administrator to consider all possible means and weigh them according to efficiency, economy and effectiveness. Finally, it could be said that the rational-comprehensive approach is too abstract and produces unrealistic decisions in practice. The incremental model of decision making, based on a political approach to public administration, argues that the rational-comprehensive model is too abstract and requires administrators to exercise a degree of rationality and comprehensiveness that is unrealistic. It stresses the need for public administrators to be responsive to the political community, and its advocates claim that it fits the public sector of the United States better because the polity operates in an incremental manner, not necessarily a rational or comprehensive one. Objectives in this model are often left vaguely-defined so that they can command the broadest political support, and steps towards improvement are made slowly and incrementally. Much more emphasis is placed on the authority of non-expert, political officials to influence and exert pressure on public administrators. The three steps associated with this model are to redefine the ends, arrive at a consensus, and make a satisfactory decision. Redefining the ends means to adjust goals in light of political realities. A reasonable level of consensus must be reached because this model sees the best test of a policy to be the level of support it generates. In contrast to the rationalcomprehensive model, a satisfactory decision is sought after instead of the best one. The incremental model’s primary limitation is that it is too conservative. Basing decisions primarily on the support they generate can lead to immobility and gridlock, making it very difficult to respond to changes in society. While it is always desirable to take responsiveness and political support into consideration, it may not always be wise to focus on these at the expense of other factors. Incremental modifications of policy can also lead to undesirable and unintended consequences; by the time a later step can be implemented, circumstances may have drastically changed, making previous steps seem disastrous in hindsight. Training the anti-Castro “Bay of Pigs” force incrementally is used as an example in the text—by the time the force was ready the Kennedy administration saw no choice but to let it invade Cuba, to the significant embarrassment of the United States. Perhaps most seriously, the incremental model is unable to direct changes in society or lead in large-scale ventures; it promotes inertia and can actually be a hindrance when there is a need to act quickly and decisively. The legal approach to decision making emphasizes adjudicatory procedure to assure fairness and impartiality among individuals, groups or entities. The intent is to prevent anyone from being treated unfairly or having their rights denied, and to ensure that decisions are made rationally and based on good information. Adjudication is a formalized procedure that identifies the facts of a situation, the competing interests involved and the balance that best fits the legal requirements or best serves the public interest. Prospective adjudication (the type specified by the Administrative Procedure Act), is used “before the fact,” such as when a utility wants to introduce a change in its service and must seek permission from a regulatory body. Retrospective adjudication occurs when a complaint against an individual, corporation or entity comes to the attention of a regulatory body. Adjudication is quasi-judicial in nature, and thus the benefits and drawbacks are similar to that of the judicial process. One of the inherent drawbacks of the adjudication and the legal approach in general is that it is a form of incrementalism, and can be just as slow and ineffective in accomplishing major policy goals. No one is planning out the “big picture” so the results of incremental changes can be undesirable and unpredictable. This approach is also very time-consuming, and limits participation in the decision making process. Finally, there is a question of whether an adversarial process is best applicable to parties who do not normally have an adversarial relationship. Briefly outline what you see as the most significant differences between public and private management environments, As a public manager, how would these differences influence your management strategies and style? Public managers operate in a very different environment than that of private managers. Federal and state constitutions define the framework of public administration and place limits on managerial discretion in every area from personnel to value assessment in decision making. For example, Congress has a great deal of authority to create agencies, set their size and budgets, define missions and set priorities. A large body of administrative law prescribes procedures to be used in policy formulation. The judiciary can also review administrative decisions and, having a final say on matters of constitutionality, can override public managers. Whereas in the private sector, the profit motive is the highest consideration, public management mostly has no such motive and is said to be serving a “higher purpose,” the public interest. Values such as transparency, representativeness, accountability and due process often take precedence over efficiency. In fact, market forces often do not affect public agencies because they do not face free, competitive markets in which their product or service is sold. Moreover, many of the goods administered by public agencies are “public goods” that no one can be excluded from enjoying and that are not diminished by use. These characteristics of non-subtractibility and non-exclusion apply to things like roads, public education and national defense. Whether a good is considered public depends largely on whether it is seen as necessary to foster the kind of political system desired by a population. Perhaps the most important difference between public and private management is that private organizations are responsible only to themselves, while public administration is considered to be subject to a sovereign, namely the citizenry. Since the Constitution leaves private activity largely unregulated, it is up to public administration in many cases to see that the private sector does not harm the public interest. Public administrators are also much more involved in politics, as they are engaged in formulation of policy that allocates resources, values and status for the nation at large. This makes politics much more salient in public management than in private.